Jack Meyer

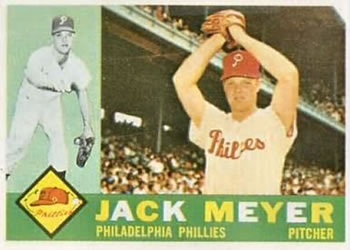

Right-hander Jack Meyer seemed destined to become a fan favorite when he debuted for the Phillies in 1955. Solidly built, blond, and handsome, the 23-year-old Philadelphia native possessed considerable pitching talent. Teammate Robin Roberts recalled years later that Meyer had “Nolan Ryan-type stuff with a sharp curveball to go with a blazing fastball.”1

Right-hander Jack Meyer seemed destined to become a fan favorite when he debuted for the Phillies in 1955. Solidly built, blond, and handsome, the 23-year-old Philadelphia native possessed considerable pitching talent. Teammate Robin Roberts recalled years later that Meyer had “Nolan Ryan-type stuff with a sharp curveball to go with a blazing fastball.”1

Meyer enjoyed an excellent rookie season, but injuries and raucous off field behavior as a member of the Phillies’ notorious Dalton Gang combined to render him another story of baseball promise unfulfilled. By mid-1960 Meyer was recovering from back surgery after a drunken scuffle, contemplating what might have been. He would pitch in one more game in 1961 before retiring for good.

John Robert “Jack” Meyer was born on March 23, 1932 in Philadelphia to Edward H. Meyer, a realtor who became a prominent Philadelphia area real estate developer, and the former Helen Coulter. Jack was the third of five brothers. Edward H., Jr., and Richard were older, James, and Robert were younger.2

Meyer starred in baseball, football, and track at Penn Charter High School, the prestigious private Philadelphia Quaker institution that was founded by William Penn himself. Jack quarterbacked the Quakers football team, while his brother James played running back.3 In track, he was a sprinter and ran cross country, but baseball was where he truly shined. He authored three no-hitters (one combined, one called after five innings) as a junior. As a senior in 1950, Jack pitched his team to an undefeated season and the Inter-Academic League championship. He earned three-quarters of his team’s victories, including a nine-strikeout two-hitter in the final game against Friends Central.4

While in high school, Jack was also named “Mr. Fastball” of 1949 by the Phillies. The Phillies held an annual contest using a “pitchometer” and challenged youngsters to compete for the title. After winning his elimination round, Meyer claimed the title and a $250 check with a pitch clocked at 85.2 miles-per-hour.5

Based on his high school performance, the New York Yankees offered Meyer $25,000 to sign, but he turned it down to attend Wake Forest College (now University) in North Carolina. In 1951, he developed a sore arm while pitching semi-pro ball and wound up signing with the Phillies for just $3,500.6

Meyer began his professional career with the Phillies’ Class D PONY League affiliate in Bradford, Pennsylvania. Fellow fun lover and future Dalton Gang member, Jim Owens, was a teammate. Meyer went 6-2 with a 5.01 ERA in 16 appearances (six starts). In 1952, he advanced to the Class B Wilmington (Delaware) Blue Rocks, where another future Dalton Gang member, Seth “Moe” Morehead, was a teammate. Meyer started 25 games, compiling a 12-10 record with a 4.15 ERA. Wildness was a problem as he walked 114 batters in just 178 innings. At the end of the season, Meyer married Joan Devereaux Wesler in Ridgewood, New Jersey. She was a graduate of Southern Seminary and attended the University of Delaware. Jack also took courses there that offseason. The newlyweds settled in nearby Wilmington.

In 1953, Meyer continued his steady climb up the minor league ladder pitching for the Schenectady (New York) Blue Jays in the Class A Eastern League. Here he teamed with another future Dalton Gang Member, Dick “Turk” Farrell. Used almost exclusively as a starter, he racked up 224 strikeouts in 218 innings, while posting a 13-11 record and 2.39 ERA.

Meyer’s fine performance earned him an invitation to spring training with the Phillies in 1954. He worked in a few intra-squad and “B” games before being shipped out with his buddy Owens to the Triple-A Syracuse Chiefs. Meyer and Owens were the talk of the International League, ranking first and second in the circuit in strikeouts, respectively. On June 3, they combined for a one-hitter, with Meyer pitching into the eighth. It was not all lollipops and roses, however, as Meyer was suspended indefinitely after a game in Montreal for a row with umpire Paul Roy in the corridor leading to the dressing rooms. Apparently, Meyer took strong exception to the ump’s ball and strike calls. He was fined $100 and reinstated the following week.7 Meyer’s 15-11 mark and 3.51 ERA helped the Chiefs finish fourth, good enough for a playoff berth with a shot to qualify for the Junior World Series.

Meyer’s pitching helped the fourth-seeded Chiefs win the International League championship. He threw a three-hit shutout against Montreal, striking out six to win, 1-0. After learning that his grandmother had passed away in Pennsylvania just before he took the mound in the 1954 Junior World Series, he pitched a two-hitter to beat Louisville, 6-3, but the Colonels eventually prevailed in the series, four games to two.8 The Phillies purchased Meyer’s contract in October, and he was on his way to the major leagues.

Coming off their excellent seasons at Syracuse, rookies Meyer and Owens were both considered as potential starters, providing an infusion of youth to an aging Whiz Kids team at 1955 spring training in Clearwater, Florida. With veteran lefty Curt Simmons experiencing arm problems and 38-year-old knuckleballer Murry Dickson requiring plenty of rest between starts, both Meyer and Owens began the season in the rotation.

Meyer debuted at the Polo Grounds on April 16, 1955 against the New York Giants. It did not go well. He gave up a home run to the first batter he faced in the major leagues, Davey Williams. Before manager Mayo Smith mercifully relieved him after 3 2/3 innings, Meyer allowed three more homers: to first baseman Whitey Lockman, opposing pitcher Jim Hearn, and another by Williams –half of the second sacker’s season output.

Things could only get better and they did. In Meyer’s next start, on April 24 at Connie Mack Stadium, he pitched eight shutout innings against the Pittsburgh Pirates in the second game of a doubleheader, striking out four (including rookie Roberto Clemente three times). Meyer’s first win and complete game would have to wait, however. The contest was called because of a curfew (due to Pennsylvania’s Blue Laws, Sunday games in Philadelphia could not continue past 7:00 p.m. in those days) in the bottom of the eighth with Earl Torgeson on third base with one out. Meyer’s RBI triple in the seventh inning had given the Phillies a 2-0 lead. When the suspended game was completed on June 28, Robin Roberts pitched the ninth inning to save Meyer’s long-delayed victory.

Meyer struck out nine Cubs over seven innings in his next outing but suffered a hard luck loss when Willie Jones’s error at third base in the fifth inning contributed to a rally that resulted in two unearned runs. By May 22, Meyer‘s record as a starter and reliever was 0-6 (his win in the suspended game had not yet been recorded). From May 24th through June 5th, however, Meyer reeled off five saves in consecutive appearances. He did not start again in 1955 but established himself as the team’s closer before such designations were used. He could be dominant. From August 2 to September 3, for example, he made 14 straight appearances without allowing an earned run. The stretch included a 3 2/3 inning outing against the Brooklyn Dodgers on August 14 in which he struck out six and walked none.

Meyer was particularly effective against the Dodgers, who would win their first World Series that year. In 21 1/3 innings against Brooklyn, Meyer held them to a .103 batting average. Reminiscing 12 years later, Mayo Smith used a bit of hyperbole describing Meyer’s mastery, saying, “Against the Dodgers, [Meyer] was the greatest I ever saw. Jack pitched 19 2/3 innings against them one year and one ball, one ball was hit out of the infield. Don Newcombe hit it. It was an out.”9 Meyer ended the year with a flourish, preserving a 3-1 victory for Curt Simmons with his league-leading 16th save when the Giants’ Bobby Hofman lined into a game-ending, 6-4-3 triple play. Overall, Meyer appeared in 50 games, struck out 97 in 110 1/3 innings, and recorded a 3.43 ERA. He finished second in the Rookie of the Year voting to Pirates centerfielder, Bill Virdon.

Over the winter, Meyer, now living in Medford Lakes, New Jersey, represented the Phillies at several sports banquets and awards ceremonies in the Philadelphia area. He seemed to be settling into his status as a big leaguer and sports celebrity. At the beginning of spring training in 1956, the Phillies announced that Meyer would be used exclusively as a reliever. Mayo Smith explained that while veterans were often cast in the role, “We wanted somebody who could fire that ball, and Meyer filled that bill.”10 Since mid-1955, Meyer “fired the ball” from what the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Allen Lewis dubbed his “gorilla stance.” Meyer, who had always stood straight up on the mound, found that by bending over and dangling his arms with his hands nearly scraping the ground in front of him, he could focus better on the catcher’s target. “There is no crowd, no bat — nothing to distract me,” he said.11 Phillies pitching coach, Whitlow Wyatt, had suggested the change, but noted that Meyer took the suggestion to the extreme. “There’s never been anything like it, in my experience anyway,” said Wyatt.12

After an indifferent spring, Meyer started 1956 with seven scoreless appearances. He won one game (5-4 over New York) by stroking the only home run of his career, a 10th inning shot off the Giants’ Hoyt Wilhelm on April 29 at the Polo Grounds. On May 11, however, pitching in relief at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, he blew a five-run lead by allowing two inherited runners to score in the sixth inning and giving up a walk-off grand slam to the Bucs’ Danny Kravitz in the bottom of the ninth. Two days later, Meyer entered a tie game in the eighth. He faced four batters, giving up a two-out triple and three walks. It gave the Pirates the lead in a game they went on to win 11-8. Meyer explained to the press that he had been taking treatment for a “crick in the neck” and while it did not appear to be serious, it may have contributed to his troubles.13

Through June 27, Meyer had an excellent 2.34 ERA, but it swelled to 4.21 by the end of July as a sore shoulder was reportedly giving him difficulty. It was hoped that moving into a starting role with more rest between outings would help, and Meyer hurled eight innings to beat the Dodgers on August 10 in his first start. He did not win again as a starter, however. On September 13, Meyer hurled all 13 innings of a heartbreaking 3-2 loss to the Milwaukee Braves. Henry Aaron beat him with an RBI triple after Meyer, with two outs, hit Danny O’Connell with a pitch. Meyer completed four games in his career but did not win any of them. He finished 1956 with a 7-11 record, only two saves, and an ERA nearly a full run-per-game higher than his rookie season at 4.41.

In January 1957, Meyer reported that he was happy with his new contract and hoped to return to being the Phillies’ top reliever, “if my arm is all right.”14 He reported to spring training early and The Sporting News’ Allen Lewis reported, “If Meyer has been inclined in the past to be less than dead serious about his work, he is immune to criticism in that respect this spring.”15 As it turned out the arm was not “all right” and Meyer made only 19 appearances (two starts) for the ‘57 Phillies. With his ERA at 16.62 after his first five outings, he was shipped to the Phillies’ Triple-A Miami Marlins affiliate for six starts. He pitched a little better after returning to the majors in mid-July, but was lightly used, often in mop up situations.

Meyer was optimistic entering 1958, thinking some offseason dental work might have cured the tooth trouble that was at the root of his arm woes.16 In February he told the Inquirer he was free of the pain that had plagued him for two years.17 In early spring training, Inquirer scribe Allen Lewis reported that Meyer appeared to be throwing with a freer motion than the previous season.18 Pitching mostly in middle relief with an occasional start, Meyer did have a bounce back year of sorts.

On June 20 against the Giants, he pitched 5 2/3 innings of scoreless relief, racking up eight strikeouts in a game the Phillies won, 5-4. On June 29, he was rewarded with his first major league victory since August 10, 1956 after hurling three scoreless innings in an extra-inning contest.

Meyer’s June, however, was not without controversy. On June 4, he threw three consecutive pitches at Cubs star Ernie Banks, before hitting him with a fourth one. After the game, umpire Frank Dascoli suggested that the new rule requiring safety head gear had led to an increase in beanballs. The incident spurred a meeting between American and National League officials to tighten beanball rules.19

Meyer really hit his stride in late August, striking out 30 batters in 20 1/3 innings and pitching to a 2.21 ERA. In one memorable game against the Pirates on September 22, he established a Phillies record by striking out the first six batters he faced out of the bullpen.20 He earned the victory in Philadelphia’s 14-inning, 3-2 triumph. Meyer finished the season 3-6 with a 3.59 ERA, his best year since his rookie campaign.

In 1959, an apparently healthy Meyer was inconsistent in the early part of the season. He had an ERA over 5.00 through the first week of June. Things had not improved much when he took the mound in the bottom of the eighth inning of a suspended game against Pittsburgh on July 21. He promptly coughed up a two-out home run to Ted Kluszewski. That landed Meyer in manager Eddie Sawyer’s frequently crowded doghouse. He did not pitch again for nearly three weeks.21 Once he got back on the mound, Meyer had his best stretch of pitching of the season and one of the best in his career. Beginning with the night cap of an August 21 doubleheader against the Giants, Meyer closed the season by hurling 23 innings without an earned run in his last 10 appearances. He lowered his season ERA from 4.46 to 3.36.

The 1960 season began in turmoil for the Phillies and ended in a hospital bed for Meyer. Immediately after the Opening Day 9-4 loss to the Cincinnati Reds, manager Sawyer abruptly quit saying, “I’m 49-years old and I want to live to be 50.”22 Meyer enjoyed a renaissance under new manager, Gene Mauch, who promised to use him as a starter. Meyer was so pleased that, when he went to shag flies in the outfield that day, he said he felt “10 feet tall.”23

Buoyed by Mauch’s confidence, Meyer’s record was 3-1 on May 22. Then disaster struck following a 4-2 Phillies loss on May 28 in Pittsburgh. Meyer had been drinking heavily. He got into an altercation with a group outside a bar, including the Inquirer’s Lewis, the Philadelphia Bulletin’s Ray Kelly, and broadcaster Byrum Saam. While reports differ, apparently Meyer was talking loudly and belligerently. When Lewis tried to settle him down, Meyer tried to punch him. Meyer’s roommate, Phillies outfielder Harry Anderson, managed to get the pitcher back to the hotel room. But teammate and inveterate prankster Turk Farrell dumped a bucket of cold water on Meyer while he slept. Meyer woke up, apparently enraged, and injured his back in the ensuing melee.24

The next day, Meyer reported the injury to Mauch. The manager sent him home to Philadelphia to get the back checked at Jefferson Hospital. Mauch described the injury as the result of “horsing around” and said the player would receive “more than a mild reprimand.”25 On June 2, the other shoe dropped. Meyer was fined 15 days’ pay (approximately $1,200) by the Phillies. At the time it was believed to be the largest fine relative to salary ever meted out by a major league club.26 Incensed, Meyer called Phillies owner Robert Carpenter from his hospital bed and told him he was quitting. He asked for his unconditional release and threatened to hire a lawyer.27 The Phillies’ brass, led by General Manager John Quinn, defended the fine based on how long Meyer would be lost to the team due to an injury that was avoidable.28

One of the reasons the fine was so stiff was because Meyer had a long history of after-hours troublemaking. In those days, beat sportswriters covering the teams rarely wrote about players’ off-field indiscretions, but a Sports Illustrated article by Walter Bingham broke with that tradition. The article, entitled “The Dalton Gang Rides Again,” identified a group of Phillies players known for late night carousing, comparing them to an outlaw band from the Old West. Bingham identified the “gang” as Phillies pitchers Dick “Turk” Farrell, Jim “Bear” Owens, Seth “Moe” Morehead, and Jack “The Bird” Meyer. These four had come up through the Phillies’ minor league system together and their reputation for late-night carousing and barroom brawls preceded them to the major leagues. Morehead had been traded to the Chicago Cubs in May of 1959, apparently opening a permanent spot in the gang for Meyer.

The gang was given its name by former Phillies pitching coach Tom Ferrick.29 Bingham quoted one National League player as saying, “They’re a wild bunch. I don’t think there is anything they won’t try.”30 Bingham ended his piece with what was probably the truest thing that could be said about these players, “The members of Dalton Gang aren’t really good enough to be so bad.”31

Meyer certainly wasn’t. He underwent surgery in July to repair his ruptured disc and fuse two vertebrae and did not pitch again in 1960. After his initial angry outburst, he was contrite and promised to work his way back into shape. That winter he said, “The doctors told me I can do anything I want to do and the only way I could have trouble with those vertebrae is if somebody hit me across the back with a baseball bat.”32 Meyer was now the longest tenured Phillies player, save for Robin Roberts. Reminded of this by Inquirer reporter Lewis, Meyer said, “That’s right. I guess it’s time I grew up.”33

As it turned out, Meyer had little time left to grow up. While his back was sound throughout spring training, he developed a recurrence of his sore arm problems. He appeared in one game in the 1961 season, pitching two innings against the St. Louis Cardinals on April 30. He gave up two runs on two hits. Shortly afterwards, he retired from baseball at age 29. In announcing Meyer’s decision, general manager John Quinn said, “Jack doesn’t think he can do it.”34

Meyer planned to return to his off-season job as a sales representative with a Philadelphia cardboard box company. He and his wife, Joan, had three children, John, Jr., Cynthia, and Raymond. The marriage ended in divorce. In 1966, Meyer was hospitalized twice with a heart ailment. On Wednesday evening, March 8, 1967, he was watching a Philadelphia 76ers-Boston Celtics basketball game on television, when he suffered a heart attack. After being rushed to the hospital, he died early the next morning. Meyer was two weeks short of his 35th birthday.35 He is buried at Lakeview Memorial Park in Cinnaminson, New Jersey.

From 1988 to 1990, Jack’s nephew Brian Meyer, a right-handed pitcher like his uncle, made 34 relief appearances for the Houston Astros.

As to why Meyer undermined his own talent with his erratic behavior, we are left only with speculation. Baseball historian William C. Kashutas, discussing the exploits of the Dalton Gang, described Meyer this way: “Blond-haired, handsome, and a stylish dresser, he suffered from an insatiable need to capture the limelight off the field.”36 Accurate or not, this impression of Meyer is likely the lasting one. Toward the end of his career, Meyer recognized that he needed to “grow up,” but by then a bad back and a sore pitching arm had robbed him of his once dazzling “stuff.”

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Malcolm Allen and Bruce Harris and fact-checked by Evan Katz.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.retrosheet.org and www.baseball-reference.com.

Notes

1 Frank Jackson, “The Turk, the Bear, the Bird: Outlaw Night Riders,” Hardball Times, October 17, 2017, https://tht.fangraphs.com/the-turk-the-bear-the-bird-outlaw-night-riders/, accessed February 8, 2021.

2 U.S. Federal Census, 1940.

3 Rosemary McCarron, “Episcopal, Charter, Doylestown Win,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 16, 1948: 16.

4 Hal Freeman, “Coatesville, Penn Charter Take Titles; St. John’s Wins,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 27, 1950: 15.

5 “Toss of 85.2 Wins Final in Pitchometer Test,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 3, 1949: 30.

6 Obituary, The Sporting News, March 25, 1967: 32.

7 “Syracuse’s Meyer Fined $100 for Row,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 9, 1954: 24.

8 “Meyer Wins Despite Sad News,” The Sporting News, October 13, 1954: 24.

9 Frank Dolson, “A Touch of Irony in Farrell’s Return,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 9, 1967: 36.

10 Allen Lewis, “Players Old, Club Stagnant; Farms Not Ready to Produce,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 2, 1956: 24.

11 Art Morrow, “Jack Meyer Credits Gorilla Stance for Success as Phils’ Relief Ace,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 20, 1956: 61.

12 Art Morrow.

13 Art Morrow.

14 Allen Lewis, “Jack Meyer First Phil to Sign; Williams Sees Great Season,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 16, 1957: 39.

15 Allen Lewis, “Meyer Earmarked for Phils’ Mound Lift If Wing is Sound,” The Sporting News, February 27, 1957: 13.

16 Allen Lewis, “Jack Meyer’s Tooth Tabbed Trouble Spot,” The Sporting News, November 27, 1957: 42.

17 “Phils Sign Meyer, Gray,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 7, 1958: 28.

18 Allen Lewis, “Phils’ Cardwell Sure He’s Improved His Curve,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 5, 1958: 40.

19 “League Presidents Will Try to Tighten Rule on Dust-Offs,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 6, 1958: 12.

20 Meyer struck out Hank Foiles, Ron Kline, Bill Virdon, Roman Mejias, R. C. Stevens, and Bob Skinner upon entering the game in the 12th inning.

21 Allen Lewis, “Long Shunned, Phils’ Meyer Starts Against Bucs,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 26, 196: 36.

22 Robin Roberts with C. Paul Rogers III, My Life in Baseball (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2003), republished as Throwing Hard Easy — Reflections of a Life in Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 49-50.

23 Lewis, “Long Shunned, Phils’ Meyer Starts Against Bucs.”

24 Walter Bingham, “The Dalton Gang Rides Again.” Sports Illustrated, June 13, 1960, https://vault.si.com/vault/1960/06/13/the-dalton-gang-rides-again, accessed February 13, 2021.

25 Allen Lewis, “Lowery Named Phillies Coach, Three Injured,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 31, 1960: 31.

26 Bingham, “The Dalton Gang Rides Again.”

27 Allen Lewis, “Fined $1000 by Phillies, Jack Meyer to Quit Baseball, Philadelphia Inquirer, June 3, 1960: 34.

28 “Quinn Reveals Brass Weighed Meyer Penalty,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 3, 1960: 34.

29 Bingham, “The Dalton Gang Rides Again.”

30 Bingham, “The Dalton Gang Rides Again.”

31 Bingham, “The Dalton Gang Rides Again.”

32 Allen Lewis, “Grown Up Meyer Signs 1961 Phillies Contract,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 11, 1961: 38.

33 Lewis, “Grown Up Meyer Signs 1961 Phillies Contract.”

34 “Arm Aches; Meyer Quits,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 10, 1961: 52.

35 “Jack Meyer, 34, Former Phillies Pitcher, Dies,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 10, 1967: 40.

36 William C. Kashutas, September Swoon: Richie Allen, the ’64 Phillies, and Racial Integration (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004), 53.

Full Name

John Robert Meyer

Born

March 23, 1932 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

March 6, 1967 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.