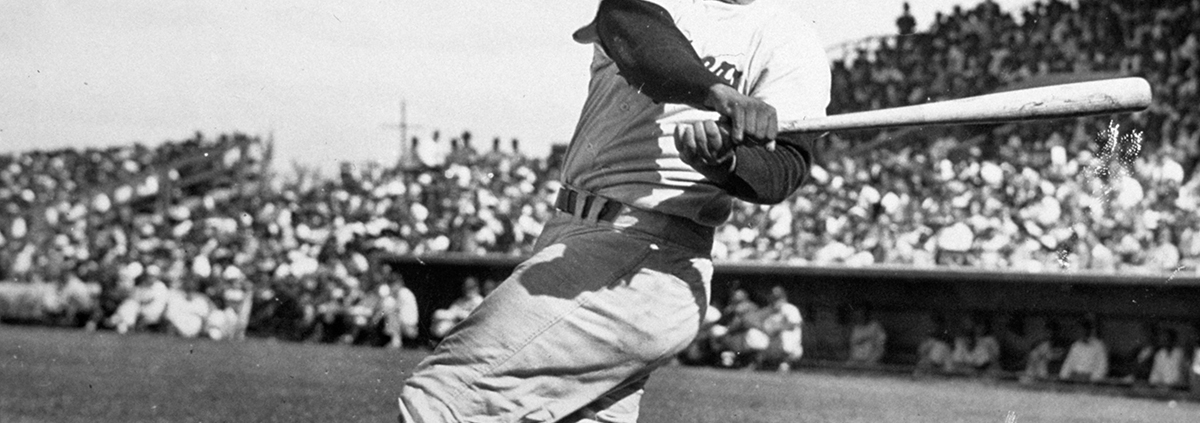

Roy Campanella

Roy Campanella was the sixth acknowledged Black player to appear in the major leagues in the twentieth century, debuting with the Brooklyn Dodgers a year after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier. Campanella went on to become the second Black player, after Robinson, to win a major-league Most Valuable Player award, and eventually became the second Black Hall of Famer, again following in Robinson’s footsteps. Campanella, however, holds the distinction of being the first Black player to capture two MVP awards, and at the time of his death in June 1993 he was the only Black player to own three MVP trophies.

Campanella spent his entire big-league career with the Dodgers, taking over as their regular catcher during the 1948 campaign and serving in that capacity through 1957, the franchise’s last season in Brooklyn. In those years the Dodgers won five National League pennants and a world championship. Prejudice and tragedy limited his major-league career to a mere 10 seasons, the color of his skin delaying his debut until he was 26 years old, and an automobile accident prematurely ending his playing days at the age of 35.

In fact, Campanella made the fewest major-league plate appearances of any Hall of Fame position player. Yet statistical guru Bill James rated him the third-best catcher of all time behind top-ranked Yogi Berra and runner-up Johnny Bench, ahead of such stalwarts as Mickey Cochrane, Carlton Fisk, Bill Dickey, and Gabby Hartnett.

Baseball-Reference.com lists Campanella’s height at 5-feet-9 and his playing weight at 190 pounds, which may have been close to the truth when he started out. The 1954 Baseball Almanac and the 1955 Who’s Who in Baseball list him at 205 pounds, which was still probably a generously low estimate considering that Campy himself pegged his weight at 215 to 220 pounds shortly before he signed with the Dodgers. Roger Kahn, author of The Boys of Summer, likened Campanella to a little sumo wrestler.1 Despite his roly-poly appearance, the squatty catcher was extremely muscular with massive arms and a bulky torso. At the plate he was a dead pull hitter with a distinct uppercut. He was graceful behind the dish, supplementing surprising agility with a cannon-like arm. He was considered an astute handler of pitchers, both White and Black – knowing when to provide encouragement and when to provide a good kick in the butt.

Roy was also tough as nails. As a Negro Leaguer, he purportedly caught four games in one day – an early doubleheader in Cincinnati and a twi-nighter in Middletown, Ohio.2 And he claimed to have caught three doubleheaders in one day in winter ball.3 He endured repeated injuries to his fingers, hands, and legs – occupational hazards of working behind the bat – but in his last appearance he established a since-broken National League record for durability by catching at least 100 games in nine straight seasons, a remarkable achievement prior to the new generation of catcher’s mitts that allow receivers to protect their throwing hand by catching one-handed.

The popular catcher was often described as gentle, unassuming, jovial, and full of life. He was a cheerleader, almost childlike in his enthusiasm. Although Campy and Jackie Robinson were teammates for nine years when there were only a handful of other Black major leaguers, they were not particularly close. In fact, there were even a few well-publicized feuds over the years. Robinson was sometimes frustrated with Campanella’s reluctance to help carry the banner for their race. “There’s a little Uncle Tom in Roy,” he once remarked.4

Despite their differences, however, Campy deeply respected Jackie and fully appreciated the sacrifices he’d made. “Jackie made things easy for us,” he said. “[Because of him] I’m just another guy playing baseball.”5

Roy Campanella was born on November 19, 1921, in Philadelphia. He had no known middle name. At the time of Roy’s birth his family lived in the Germantown section of the city, but they moved to an integrated section in the northern part of the city known as Nicetown when Roy was 7 years old. He was the product of an interracial marriage, an African-American mother and a father of Sicilian descent – something of a novelty in those days. He attended Gillespie Junior High and Simon Gratz High School, although he left high school before graduating. Growing up, the light-complexioned youngster was tauntingly called “half-breed” by kids of both races, which helped him develop into a pretty good scrapper. In fact, he briefly fought as a Golden Gloves boxer. Roy, the baby of the family, had three older siblings. His brother, Lawrence, about 10 years older, wasn’t around very much when Roy was growing up. His sisters, Gladys and Doris, were both excellent female athletes.

John Campanella, Roy’s father, made his living selling vegetables and fish out of a truck and later operated a grocery store while Roy’s mother, Ida, ran the household. Growing up in the middle of the Depression, Roy had to work as a youngster. He helped his father, sold newspapers, shined shoes, and had a milk route as a teenager.

Through high school Roy attended integrated schools and played for integrated football, basketball, and baseball teams. Blacks were in the minority, but he was invariably chosen as the team captain, whatever the sport. Though he participated in other sports, baseball was his passion. He watched many a game at nearby Shibe Park from the top of an adjacent building. By the time he entered high school, he’d abandoned his early aspirations to be an architect and was determined to be a professional baseball player.

Gradually word of his prowess on the diamond spread. While in high school, he was reportedly offered an opportunity to work out with the Phillies, but the club rescinded the invitation when they discovered he was Black.

At the tender age of 15 in 1937, Campanella began his professional baseball career with a top-notch semipro team, the Bacharach Giants. Mama Campanella didn’t want her baby to play pro ball with grown men, but when they promised to pay him more for a weekend of catching than his father made in a week, a compromise was reached. Despite his youth, Campanella performed so impressively for the Bacharach Giants that the Washington Elite Giants of the Negro National League soon signed him to spell veteran receiver and manager Biz Mackey on weekends. Roy was an indifferent student to begin with, but after he spent his summer vacation barnstorming with the Elite Giants, schoolwork could no longer hold his attention.

After he turned 16, Roy quit school to play full time for the renamed Baltimore Elite Giants. In 1939 the precocious 17-year-old youngster took over the regular catching chores after Mackey was traded to the Newark Eagles in mid-season and helped lead the Giants to playoff victories over the Eagles and Homestead Grays. His hitting improved and he began showing more power in 1940, and was soon challenging the legendary Josh Gibson’s status as the best catcher in Negro baseball. While still a teenager, he caught the entire 1941 Negro League East-West All-Star Game for the East, winning MVP honors for his excellent defensive work.

After he turned 16, Roy quit school to play full time for the renamed Baltimore Elite Giants. In 1939 the precocious 17-year-old youngster took over the regular catching chores after Mackey was traded to the Newark Eagles in mid-season and helped lead the Giants to playoff victories over the Eagles and Homestead Grays. His hitting improved and he began showing more power in 1940, and was soon challenging the legendary Josh Gibson’s status as the best catcher in Negro baseball. While still a teenager, he caught the entire 1941 Negro League East-West All-Star Game for the East, winning MVP honors for his excellent defensive work.

Campanella had married a Nicetown girl, Bernice Ray, in 1939 and they had two girls. With three dependents his draft status was 3-A when World War II broke out, so he was never called for active duty, although he was required to work in war-related industry for a time.

During the 1942 Negro League season, Campanella jumped to the Monterrey Sultans of the Mexican League after a contract dispute with the Elite Giants. He remained in Mexico for the 1943 season before returning to Baltimore for the 1944 and 1945 campaigns. Though he regained his All-Star status, he deferred to Josh Gibson in the 1944 game, playing a few innings at third base. But he was back behind the plate for the 1945 Classic.

In October 1945 Campanella caught for a Black all-star team organized by Effa Manley against a squad of major leaguers managed by Charlie Dressen in a five-game exhibition series at Ebbets Field. Dressen, a Dodgers coach at the time, approached Campanella during the series to arrange a meeting with Dodgers general manager and part-owner Branch Rickey later that month. Campanella spent four hours listening to Rickey, whom he later described as “the talkingest man I ever did see,” and politely declined when Rickey asked if he was interested in playing in the Brooklyn organization.6 Campy thought he was being recruited for the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers, a new Negro League outfit that Rickey was supposedly starting. A few days later, however, he ran into Jackie Robinson in a Harlem hotel. After Robinson confidentially told him he’d already signed with the Dodgers, Campy realized that Rickey had been talking about a career in Organized Baseball for him. Afraid that he’d blown his shot at the big leagues, he fired off a telegram to Rickey indicating his interest in playing for the Dodgers just before leaving on a barnstorming tour through South America.

The 1946 spring-training season was already under way by the time Campanella returned from South America and reported to the Dodgers office in Brooklyn. The Dodgers didn’t quite know what to do with him or pitcher Don Newcombe, another Negro League star they’d signed. Robinson and former Homestead Grays hurler Johnny Wright were already slated for Montreal, and most of the organization’s other minor-league franchises were located in the South or the Midwest. They tried to send Campanella and Newcombe to Danville of the Class-B Illinois-Indiana-Iowa (Three I) League, but the circuit wouldn’t accept Black players. The Dodgers then checked with their Nashua, New Hampshire, farm club in the New England League, a lesser regarded Class-B circuit, where young general manager Buzzie Bavasi welcomed the opportunity to add two such talented Black players to their roster.

Like most of the first generation of Black players to cross the color line, Campanella took a steep pay cut to enter Organized Baseball and was forced to start at a level far below his ability. A top star in the Negro leagues, he found himself competing against a bunch of inexperienced kids, most of whom would never rise above Class-A ball. Furthermore, he would be making only $185 a month for six months in the minors rather than the $600 a month he’d been earning with the Baltimore Elite Giants.

With Nashua in 1946, Campanella hit .290 and drove in 96 runs to win the New England League MVP award. Early in the season, Nashua manager Walter Alston, who doubled as the club’s first baseman, asked Campy to take over the team for him if he ever got tossed out of a game. His reasoning was that Roy was older than most of the players and they respected and liked him. Sure enough, in a June contest Alston was ejected in the sixth inning and Campy became the first Black man to manage in Organized Baseball. Moreover, his strategic move resulted in a comeback victory when he called on the hard-hitting Newcombe to pinch-hit and was rewarded with a clutch home run.

Roy’s experience in Nashua also changed his parents’ life. Fences around the New England League were virtually unreachable, and a local poultry farmer offered 100 baby chicks for every Nashua home run. At the end of the season, Campy collected 1,400 chicks as reward for his 14 homers (a team-leading 13 in the regular season and one in the playoffs). He had them shipped to his father, who promptly began a farming business on the outskirts of Philadelphia.

Campanella went to spring training with the Dodgers in Havana before the 1947 season. He was listed on the Montreal roster, along with Robinson, Newcombe, and Roy Partlow, a left-handed pitcher. Robinson, of course, was promoted to the Dodgers, Newcombe was sent back to Nashua, and Partlow was released, leaving Campanella the only Black player in the International League. That season, while Robinson was burning up the basepaths as the first Black player in the majors in the twentieth century, Campanella starred in the International League. Veteran catcher Paul Richards, managing the Buffalo Bisons called him “the best catcher in the business – major or minor leagues.”7 With his extensive Negro League experience and an excellent Triple-A season under his belt, the 26-year-old receiver was ready for major-league duty.

Unfortunately, the Brooklyn Dodgers weren’t yet ready for him. Brooklyn’s regular catcher was Bruce Edwards, who in 1947 posted an excellent .295 batting mark, drove in 80 runs, and finished fourth in National League MVP balloting, the highest ranking of any Dodger. In addition, Edwards was a fine defensive backstop and was almost two years younger than Campy.

According to popular legend, Rickey wanted Campanella to break the racial barrier in the American Association, the Midwestern Triple-A circuit, before he became established with the Dodgers. Therefore, he attempted to conceal Campanella’s skills from the press by carrying him on the preseason roster as an outfield candidate – a position for which Campanella was clearly ill-suited. A less Machiavellian, but plausible, explanation might be that Rickey didn’t want to cause dissension or put too much pressure on Campanella by competing with the popular Edwards. Whatever the reason, the Dodgers brought Campanella to camp as an outfielder and even tried him out at third base.

But Edwards had injured his arm in the offseason, and it failed to come around in the spring of 1948. Manager Leo Durocher, back in command of the Dodgers after a year’s suspension, fully appreciated Campanella’s talents and wanted to insert him behind the plate in place of the injured Edwards. But Rickey did not want to put the rookie catcher’s skills on display. The issue apparently became a source of friction between Durocher and Rickey.

Though Campanella broke camp with the Dodgers, the plan was to send him down to their St. Paul American Association farm club when rosters had to be trimmed to 25 players on May 15. He made his big-league debut against the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds on Opening Day. Gil Hodges, who hadn’t made the move to first base yet, started behind the plate in place of Edwards, but went out for a pinch-hitter in the top of the seventh. In the bottom half of the inning, Campanella took over behind the plate with the Dodgers down 6-5. With ace reliever Hugh Casey on the mound, the Giants went scoreless for the final three innings while the Dodgers scored two runs to win the game. Campanella got to the plate in the top of the eighth inning and was promptly drilled by Giants reliever Ken Trinkle – the type of welcome that many more Black hitters would receive in the early days of baseball’s integration era.

Campanella made his second big-league appearance three days later, replacing Hodges to finish up a 10-2 Phillies blowout. Then on April 27, after a pair of losses, Durocher defied Rickey and started Campy at catcher in Boston. He went hitless but acquitted himself well behind the plate. Though Brooklyn lost, wildman Rex Barney held the Braves to three runs with Campanella calling the pitches. Rickey was reportedly incensed and ordered Durocher not to use Campanella behind the plate again. This time Durocher complied. Campy warmed the bench until he was farmed out to St. Paul on May 15.

The American Association’s first Black player broke the league’s color barrier with a disastrous performance, going hitless and fanning twice in four at-bats, and making an error on a pickoff attempt. But he was soon terrorizing the opposition. In 35 games, Campy batted .325, slammed 13 homers, and drove in 39 runs, forcing the struggling Dodgers to recall him.

When Campanella joined the Dodgers’ lineup on July 2, 1948, the defending National League champions had lost five straight and were languishing in sixth place with a 27-34 record. From that point on they won 57 while losing 36, a .613 pace – better than the .595 overall winning percentage posted by the pennant-winning Braves. Even more remarkable was the fact that the Dodgers won 50 of the 73 games that Campanella started after his recall, an incredible .685 mark. His installation behind the plate was the last in a series of moves orchestrated by Durocher to turn the club around. Three days earlier Gil Hodges, who had acquitted himself well behind the plate filling in for the injured Edwards, was shifted to first base, allowing Jackie Robinson to move over to his natural second-base position. Unfortunately for Durocher, he didn’t stay around long enough to enjoy the results, as he left the Dodgers to take over the reins of the New York Giants a week after Campanella’s recall.

For his rookie year, Campanella batted .258 with 9 homers in 83 games and led National League catchers in percentage of runners caught stealing. He even garnered eight points in the MVP voting despite playing only half the season.

In 1949 Campanella hit .287 with 22 home runs and 82 runs batted in, cementing his hold on the Dodgers’ first-string catching job. During the campaign, Don Newcombe was called up from the minors, combining with Campanella to form the major leagues’ first Black battery. The pair had developed an excellent rapport at Nashua three years earlier and, under Roy’s expert handling, the volatile young flamethrower quickly became the ace of the staff. Both Campanella and Newcombe made the 1949 National League All-Star squad, joining Robinson and Cleveland’s Larry Doby in becoming baseball’s first Black All-Stars. Campanella replaced starting catcher Andy Seminick in the fourth inning and went the rest of the way, beginning a streak in which he would catch every All-Star inning for the National League until Smoky Burgess relieved him in the eighth inning of the 1954 contest. Campanella also displayed his toughness later in the 1949 season when, after a beaning by Bill Werle of the Pirates, he rejected the doctor’s recommendation to take a few days off and rejoined the lineup the next day.

Campanella upped his homer total to 31 in 1950 and batted .281, firmly establishing himself as the best catcher in the National League, if not all of major-league baseball. He caught all 14 innings in that summer’s All-Star Game. In September he suffered a compound fracture from a foul tip off his right thumb and missed starting 11 consecutive games behind the plate – the Dodgers dropping seven of them. Campy’s absence probably cost Brooklyn the pennant as they ended up losing to the Phillies on the last day of the season to finish two games off the pace.

In spring training before the 1951 season, Campy took another foul tip on his right thumb that chipped the bone and forced him to play in pain all year. Later, a beaning by Turk Lown of the Cubs sent him to the hospital for five days with a concussion and he experienced dizziness for weeks thereafter. Nevertheless, he batted a career-high .325 with 33 homers and 108 runs batted in, and finished third in the league in doubles, slugging, and OPS. On the last day of the regular season, which ended in a tie between the Dodgers and the New York Giants, Campanella aggravated a leg injury he had received in a collision at home plate a few days earlier. He gamely struggled through the first game of the three-game playoff series, but realized he was hurting the team and sat out the last two contests. It’s widely believed that if Campanella had been behind the plate for the third game, he would have been able to nurse his pal Newcombe through the ninth inning – and Bobby Thomson would never have come to the plate to hit his historic pennant-winning home run. In MVP voting Campanella beat out Stan Musial of the Cardinals for the National League award. In the American League Yogi Berra of the Yankees captured his first MVP award. It was the first year in history that catchers won the annual award in both leagues.

Campanella followed his brilliant 1951 campaign with a disappointing performance in 1952. After he had endured numerous minor injuries early in the season, a foul tip chipped a bone in his left elbow in July. He played with the injury for 10 days before his arm had to be placed in a cast for nearly two weeks. His season average fell to .269 and he hit only 22 home runs. In the Dodgers’ seven-game World Series loss to the Yankees, he managed only six singles.

In 1953 Campanella reported to spring training in great shape and stayed remarkably healthy through the season. And what a great season it was! He batted .312 and his 41 home runs and league-leading 142 RBIs established all-time highs for major-league catchers that stood until 1970. Campanella’s home-run total was the third-highest in the league and he ranked third in slugging and fourth in OPS as he led the Dodgers to their second straight National League pennant. But in the first game of the World Series, Allie Reynolds of the Yankees hit him on the hand with a pitch and he was unable to properly grip the bat through the club’s second straight Series defeat. His second National League MVP award, however, was a foregone conclusion.

In spring training before the 1954 campaign, Campanella injured his left wrist and hand when he slid awkwardly trying to break up a double play. The bone on the heel of his hand was fractured and pieces that chipped off were impinging on the nerve. Surgery was recommended, but Campanella tried to play with the painful condition. He finally agreed to an operation in early May. Initial estimates put the recovery time at eight to 10 weeks, but Campy returned to action in less than a month. Numbness in the hand bothered him all year, however, resulting in a dismal .207 batting average with 19 homers. Campanella’s value to the Dodgers, even at less than full strength, was demonstrated by the fact that the club posted a .623 winning percentage for the 106 games he started, compared with .542 without him. At season’s end, the Dodgers trailed the Giants by five games. Insult was added to injury when their crosstown rivals defeated the Cleveland Indians to capture the world-championship banner that had proved so elusive to the Dodgers. After the season Campanella submitted to further surgery on the hand to remove scar tissue and repair nerve damage.

It was feared that Campanella’s hand injuries could mean the end of his career, or at least drastically curb his productivity. But the 33-year-old veteran made a miraculous comeback in 1955. At midseason he was leading the league in hitting when he was hit on the left kneecap by a foul tip that broke a bone spur loose from his patella. The knee was in a cast for more than two weeks and he missed his first All-Star Game since 1949, although he was picked for the team. Nevertheless, Campy was still challenging for the batting title late in the season, when the rigors of catching every day caused his hands to start bothering him again and his hitting fell off. He still finished with a .318 batting average, slammed 32 home runs, and knocked in 107 runs, despite sitting out more than 30 games. He again drove the Dodgers to the National League pennant, and led them to victory over the Yankees in the World Series. In National League MVP balloting he prevailed for a third time. In the American League, Yogi Berra also captured his third MVP trophy. Four years after Campy and Yogi became the first catchers to win MVP honors in the same season, they became the second and last duo to accomplish the feat (through the 2022 season).

But thousands of games behind the bat had taken a toll, and Campanella’s 1956 season was ruined by more hand problems. His twice-operated-on glove hand, which had begun tormenting him again late the previous year, still ached. Then he broke his thumb when he slammed his right hand against the hitter’s bat while attempting a pickoff throw to first, an injury that bothered him all year. He ended the campaign with a .219 batting average, but still managed 20 homers as the Dodgers captured their last pennant in Brooklyn. In the World Series, another seven-game loss to the Yankees, he hit only .182 with no homers and seven strikeouts.

Campanella decided to undergo another operation after the 1956 campaign to relieve the pain in his left hand, but the Dodgers insisted that he go on their offseason exhibition tour of Japan first, which drastically cut into his recovery time. With his hands still troubling him in 1957, he missed more than 50 games and hit .242 while belting just 13 home runs, and failed to make the All-Star squad for the first time since his rookie year. Brooklyn fell to third place in the National League amid persistent rumors of a move to the West Coast. Shortly after the Dodgers’ last game, it was officially announced that the franchise would relocate to Los Angeles for the 1958 season.

Campy loved playing in Brooklyn and like most of the Dodger veterans hated the prospect of moving. But his hands were feeling better than they had in years and he was starting to warm up to the idea of taking aim at the 295-foot left-field fence of the Los Angeles Coliseum, an oval-shaped football stadium that would serve as the club’s makeshift home field.

But in January 1958, just before he was due to report for spring training, Campanella was permanently disabled in a traffic accident. He had successfully invested in a liquor store in central Harlem, called Roy Campanella Choice Wines and Liquors, earlier in his career and worked there in the offseason. He normally left for home in the early afternoon, but on that fateful day he’d stayed in town to plug a YMCA fund-raising drive on a local television show. The appearance was canceled, but he stayed to help close up the liquor store before leaving for his home in Glen Cove, on the North Shore of Long Island. The Chevy station wagon Campy normally drove was in the shop for repairs, and he was driving a much lighter rental car when he lost control of the vehicle on an icy street. He hit a telephone pole and the car flipped over, pinning him under the steering wheel. Roy’s neck was broken and his spinal cord was severely damaged, paralyzing him from the chest down.

But in January 1958, just before he was due to report for spring training, Campanella was permanently disabled in a traffic accident. He had successfully invested in a liquor store in central Harlem, called Roy Campanella Choice Wines and Liquors, earlier in his career and worked there in the offseason. He normally left for home in the early afternoon, but on that fateful day he’d stayed in town to plug a YMCA fund-raising drive on a local television show. The appearance was canceled, but he stayed to help close up the liquor store before leaving for his home in Glen Cove, on the North Shore of Long Island. The Chevy station wagon Campy normally drove was in the shop for repairs, and he was driving a much lighter rental car when he lost control of the vehicle on an icy street. He hit a telephone pole and the car flipped over, pinning him under the steering wheel. Roy’s neck was broken and his spinal cord was severely damaged, paralyzing him from the chest down.

Roy Campanella, once the best catcher in the National League, if not all of major-league baseball, would spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair.

The Dodgers continued to pay Campanella his salary while he was hospitalized for surgery and rehabilitation for almost a year after the accident. Though he never got a chance to play for the Dodgers in Los Angeles, a crowd of 93,103 fans, the largest in baseball history to that date, jammed the Los Angeles Coliseum on May 7, 1959, for a benefit exhibition game between the Yankees and Dodgers – a tribute to the former Brooklyn great.

Campanella’s personal life began to unravel in the wake of his accident. His teenage marriage to Bernice Ray had quickly ended in divorce. With Roy away so much of the time, traveling the Negro League circuit or playing winter ball in the Caribbean, Bernice continued to live with her parents and the couple had gradually drifted apart. In 1945 Roy married Ruthe Willis, a fine athlete herself. They had two sons and a daughter together and Ruthe’s son from a previous marriage also lived with them.

But Ruthe was unable to adjust to Roy’s physical disability. In 1960 he sued for a legal separation; a messy affair that kept the city’s tabloid press busy. In 1963 Ruthe suffered a fatal heart attack at the age of 40 before a divorce was finalized. On May 5, 1964, Roy married Roxie Doles, who remained at his side for the remainder of his life.

After enduring years of therapy, Campanella regained some use of his arms. He eventually was able to feed himself, shake hands, and even sign autographs with the aid of a device strapped to his arm, though he remained dependent on his wheelchair for mobility. Through it all he managed to maintain the positive, upbeat attitude that was his trademark and became a universal symbol of courage. In 1969, the same year he was inducted into the Hall of Fame, he received the Bronze Medallion from the City of New York, the highest honor the city confers upon civilians, awarded for exceptional citizenship and outstanding achievement. Three years later the Dodgers retired his uniform number 39 along with Robinson’s number 42 and Sandy Koufax’s 32.

Though Campanella stayed in New York, continuing to operate his liquor store and hosting a radio sports program called “Campy’s Corner,” he remained a part of the Dodgers family. He worked in public relations, helped with scouting, and served as a special instructor and adviser at the club’s Vero Beach spring-training facility. In 1978 he moved to Los Angeles and took a job as assistant to the Dodgers’ director of community relations, Don Newcombe, his former teammate and longtime friend.

On June 26, 1993, Campanella succumbed to a heart attack in Woodland Hills, California. He lived to be 71, far exceeding the normal life expectancy for someone in his condition. In 2006 he was honored with a US postage stamp bearing his image, and later that year the Dodgers announced the creation of the Roy Campanella Award, to be given annually to the Dodger who best exemplifies Campanella’s spirit and leadership.

Roy Campanella’s lifetime batting average for 10 major-league seasons was .276 and he hit 242 home runs while driving in 856 runs in 1,215 games. His 1953 totals of 41 homers and 142 RBIs stood as single-season highs for a catcher until Johnny Bench hit 45 homers and drove in 148 runs in 1970. Bench, however, played a 162-game schedule rather than the 154 contests played in 1953, and had 86 more at-bats than Campanella.

Campanella shone just as brightly on defense. Sportswriters often referred to him as “The Cat” because of his feline-like quickness blocking stray pitches or pouncing on bunts in front of home plate. He led National League catchers five times in percentage of runners caught stealing, and his career rate of 57 percent is the best all-time among catchers who appeared in more than 100 games.

But the most revealing statistic is the three Most Valuable Player awards Campanella earned in his all-too-brief career. When he was honored for the third time, in 1955, Stan Musial was the only other National Leaguer to have accomplished the feat, while Joe DiMaggio, Jimmie Foxx, and Yogi Berra were the only American Leaguers to have done so. Since then, only the names of Mickey Mantle, Mike Schmidt, Barry Bonds, Álex Rodríguez, and Albert Pujols have been added to the exclusive list.

Nonetheless, Campanella’s career is sprinkled with what-ifs. It’s fair to say that, even with the premature end to his career, Campy’s third place ranking on Bill James’s catchers list might have been higher if he hadn’t been denied the opportunity to play in the major leagues at an earlier age. It’s also probably realistic to assume that he wouldn’t have had to wait six years after gaining eligibility to be elected to the Hall of Fame.

If circumstances had been right, Campanella could have been the first Black player in the big leagues. Back in 1943, he had been invited to Forbes Field to work out for the Pittsburgh Pirates, but team president William Benswanger succumbed to peer pressure and canceled the tryout.

And if not for the accident, Campanella might well have become the major league’s first Black manager. Before joining the Dodgers, he managed the Caracas club in the Venezuelan Winter League for a few seasons. In 1946 the 25-year-old skipper’s charges included Newcombe, Sam Jethroe, Harry Simpson, and Luis Aparicio, Sr., father of the Hall of Fame shortstop. Before his accident the Dodgers had already approached Campanella about a future coaching or managing in the minor leagues after his career ended.

In his autobiography It’s Good to Be Alive, Campanella reminisced about the happiest days of his life in Brooklyn: “That’s where I wanted to finish my playing career. I got my wish all right, but in a much different way.”8

Photo credits

SABR-Rucker Archive.

Sources

This article was adapted from the author’s book The Black Stars Who Made Baseball Whole: The Jackie Robinson Generation in the Major Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004).

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and a number of other sources, including:

Campanella, Roy II, “Roy Campanella” in Cult Baseball Players, Danny Peary, ed. (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990), 251-9.

Golenbock, Peter, Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers (New York: Putnam’s, 1984).

James, Bill, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2001).

Peterson, Robert W., Only the Ball Was White (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Carol Publishing, 1970).

The Sporting News, March 24, 1948, 22.

Clark, Dick, and Larry Lester, The Negro Leagues Book (SABR, 1994, statistical section)

Notes

1 Roger Kahn, The Boys of Summer (New York: Harper and Row, 1971), 327.

2 Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstadt, Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers, 1947-1959 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1994), 28.

3 Kahn, 327.

4 Kahn, 327.

5 Moffi and Kronstadt, 27.

6 Roy Campanella, It’s Good to Be Alive (New York: Dell, 1959), 109.

7 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 223.

8 Roy Campanella, 11.

Full Name

Roy Campanella

Born

November 19, 1921 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

June 26, 1993 at Woodland Hills, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.