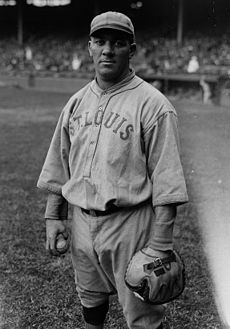

Pat Collins

Pat Collins, back in the minors in 1925 after six frustrating seasons with the St. Louis Browns, found himself in the right place at the right time in 1926. Collins saw his playing time bottom out with the Browns in 1924 and the 28-year-old was relegated to the American Association. His response to playing more regularly was a fine 1925 season with the St. Paul Saints.

Pat Collins, back in the minors in 1925 after six frustrating seasons with the St. Louis Browns, found himself in the right place at the right time in 1926. Collins saw his playing time bottom out with the Browns in 1924 and the 28-year-old was relegated to the American Association. His response to playing more regularly was a fine 1925 season with the St. Paul Saints.

New York Yankees masterminds Miller Huggins and Ed Barrow, looking for catching depth, took note and signed Collins for the 1926 season. There, alongside Murderers’ Row, he fit well into the catching rotation until 1929, earning trips to the World Series each season, two championship rings, and Series participants’ money. Despite limited Series playing time, Collins still had a personally satisfying day in the game that closed the vaunted Yankees’ 1927 sweep.

But Collins’s brush with glory in New York and his major league career both ended abruptly with the arrival of Bill Dickey. Collins was odd man out as the Yankees sold him to the Boston Braves after the 1928 season; by mid-spring 1929 he was back in the minors again. He never returned. With his playing career over, Collins, 35 years old and back home in Kansas City, briefly and unsuccessfully attempted to remain in the game as a minor league franchise owner. He then turned to the tavern and club business and kept in touch with baseball through the newly-arrived Kansas City Athletics. But a part of his later life, which was shortened by heart disease, was occupied with defending income tax evasion charges.

Tharon Leslie Collins1 was born on September 13, 1896, in Sweet Springs, Saline County, Missouri. In the 1890s, Sweet Springs was a village of approximately 1,100 people in north-central Missouri roughly 65 miles east of the Kansas City metropolitan area on the Missouri-Kansas state line.2 Of Greek and Irish ancestry, he was known as “Pat” throughout his life.3

Pat was the third child and first son born to Julius Goodwin Collins and Sarah Parthenia Nightwine Collins, natives of Missouri and Kansas, respectively. Sisters Ola and Hallie preceded him; brother Rathael followed. While the children were still young, Julius seems to have dropped out of the family dynamic; Sarah appears as a 31-year-old head of household in the 1900 census, with the family still living in Sweet Springs. By 1910, she was still head of the household but additionally designated as a widow.4 Sometime after 1900 she had moved the family from Sweet Springs to Wyandotte, Kansas, just outside Kansas City. Sarah ran a boarding house there with five lodgers reported in 1910. With the four children, she was obviously busy tending to a 10-person household.

Relocated to the Kansas City area with his family as a youngster, Pat maintained his home there for the rest of his life. He played semipro baseball, starting with the Soldiers’ Home team in 1911 when he was 15. He developed into a solidly built (5-feet-10, 178 pounds) catcher who both hit and threw from the right side.5 By 1916 he was good enough for tryouts with the Kansas City Blues of the American Association (Class AA, then the highest minor league classification) and their affiliated Beaumont Oilers of the Class-B Texas League.6 Neither look developed into a playing opportunity, but Pat caught on as a catcher and outfielder with the 1917 Joplin (Missouri) Miners, an unaffiliated Class B club in the Western League.7 Getting his professional start there at age 20, he established himself as a feisty second-line backstop.8 Collins hit .226 in 85 games but showed some pop and speed with 11 doubles and six triples.

He was back with Joplin again in 1918 and a fan favorite. When he hit the first ball out of the year-old Joplin ballpark on May 9, he “was presented with $63 by admiring friends.”9 But Collins was a healthy 21-year-old and, with the United States in World War I, he had registered for the draft earlier in 1918. By late summer he was playing not for Joplin but for the Navy’s Great Lakes Training Station club in a St. Joseph, Missouri, exhibition game. He was heralded as one of “many well-known stars again in familiar haunts.”10 While stationed at Great Lakes, he wangled furlough time to marry the former Clementine Eunice “Daisy” Harshfield in Kansas City on October 31, 1918. The couple remained together until his death but was childless.

After the war ended in November, Collins was discharged on December 24, 1918. He had played 51 games for Joplin before his Navy service and upped his batting average to .257. But he had a breakout season in 1919, batting .316 in 316 at bats with a .516 slugging mark that included 36 extra-base hits, 10 of them home runs, second in the Western League. His break came in late August 1919 when the St. Louis Browns purchased the rights to Collins and a battery mate, lefty Rolla Mapel, from Joplin for a reported $6,000. They were initially set to report at the end of the season, but the plan changed to have them join the Browns in time to accompany the club on an Eastern road trip, starting on September 3.11

Collins arrived in St. Louis in time to make his major league debut before the road trip started as an unsuccessful pinch hitter for pitcher Ernie Koob in the ninth inning of a 5-2 loss to the Detroit Tigers on August 29. He then mopped up for veteran catcher Hank Severeid or pinch-hit in Detroit, Boston, New York, and Washington before getting manager Jimmy Burke’s call to start the first game of a doubleheader on September 18 in Washington, catching the Browns’ ace, spitballer Allen Sothoron.12 Collins logged his first major league hit, a single off Senators rookie Al Schacht, and scored a run as the Browns lost, 12-3.13 Burke gave him three more starts over the rest of the season. He had two more hits including a double, scored another run, and caught Lefty Leifield’s shutout at Philadelphia on September 20.

Burke was “particularly pleased” with Collins and three other rookies who saw action during the trip. He was “certain” that Collins would “qualify for [a] battery position” for 1920, notable in that Severeid, Josh Billings, and Wally Mayer, all of them with more experience, would be in the mix.14 Considered “a brilliant prospect” by the Browns, they carried him in Mayer’s place as their third catcher for 1920.15 But Severeid and Billings got most of the work and Collins petitioned for a return to the minor leagues. Instead, St. Louis used him for occasional pinch hitting, which Collins had disliked from his days at Joplin, Pat figured that “he could go into a fast minor league for a season and come back to the big show next spring ready to step into a first string job.”16 Instead, he played in only 23 games and batted a flat .214 in 32 plate appearances.

In 1921, when Lee Fohl replaced Burke as manager, Collins moved ahead of Billings, but Severeid batted 531 times to Collins’s 131. Collins hit his first major league home run off the Tigers’ Hooks Dauss on June 23. He was batting .343 by then, but cooled to .243 by the end of the season. The Browns finished third in the American League; Collins, still making rookie-level pay, augmented that with a share of the team’s aggregate $15,000 split from World Series receipts.17

The 1922 Browns made a run at the powerhouse Yankees for the American League pennant as Collins solidified himself behind Severeid and added the first two pinch-bit home runs of his career on May 13 and June 3. St. Louis trailed by a half-game when the Yankees came to town for a showdown series September 16-18. After the Yankees took the first and third games, the Browns dropped to as many as 4½ games back, but closed with a four-game winning streak that left them only a game short when the season ended. Fohl started Collins in three of those games and he responded with two doubles and two RBIs to cap a .307 season.

Fohl also used Collins to spell future Hall of Famer George Sisler for five games at first base in 1922.18 Possibly seeing some future at a position other than catcher, Collins tried winter baseball in the 1922-23 offseason. He signed on with the Cuban League Marianao (Havana) club and played first base—but only for two games, hitting .250. Accompanying him in the venture was Bill Burwell, his fellow Kansan, former Browns teammate (1920-21), and later player-manager of Collins’s minor league club.

Collins was back—again behind the durable Severeid—with the Browns in 1923 but had a disappointing season. He did drive in 30 runs in 181 at bats and added another two pinch-hit home runs, but he hit a disappointing .177. On June 8, however, he became a small bit of baseball trivia when he both pinch-ran, then pinch-hit, in the same game.19

Collins had steadily gained weight riding the bench in 1923. Seeking to burn off the excess, he worked as a hod carrier in Kansas City over the 1923-24 offseason, sensing that by this point that he needed to “make a great fight to stick around in big-league company.”20 Coach Jimmy Austin had replaced Fohl as St. Louis manager on August 8, 1923, but the change yielded no positive impact on Collins’s playing time. Austin was back to coaching in 1924, with Sisler installed as player-manager. A slimmer Collins made the club again and although Severeid was back for his 13th major league season and still the everyday catcher, Sisler gave Collins several starts early in the season. He hit well, but after June 21, when rookie Tony Rego arrived, Collins, by then 27, was again a third-stringer. He finished the 1924 season with a .315 batting average, his major-league career high—but was punchless. Of his 11 RBIs for the season, four came on one June 16 grand slam swing.

A shining prospect heralded by the Browns in 1920, Collins was now a disposable part. The club traded him with three other players and cash to St. Paul on January 3, 1925, for catcher Leo Dixon.21 “Suits me,” Collins said. “I have wanted to get with a club where I could take my regular turn behind the plate.” He looked forward to hitting in the St. Paul ballpark, with its short left field. “I’ll at least be swinging,” he promised.22 Collins made the most of the opportunity. He stepped in as the Saints’ everyday catcher, hit .316, slugged .505 with 19 home runs, and parlayed the season into a $6,000 contract for 1926 with the New York Yankees.23

After winning American League pennants in 1921, 1922, and 1923, the Yankees had slipped to second place in 1924. They fell all the way to seventh, 28½ games behind Washington, in 1925—one big reason being Babe Ruth’s off year.24 The club liked the looks of Collins’s hitting at St. Paul, and the New York press was high on him as well. “You will recognize Pat Collins, who used to catch for the Browns. Pat’ll be a big help. He’s a heavy hitter and a long distance driver. He’s a good catcher, too, and will get plenty of work next summer.”25

Manager Huggins followed the instinct that had led him to Collins, by then 29, and installed the reclamation as his primary catcher in 1926. It paid off quickly. Collins’s three RBIs helped New York win a wild 12-11 opener on April 13 at Fenway Park. He continued to hit, remaining above .300 until May 4. Popular New York baseball writer Joe Vila, stringing for The Sporting News, noted on the front page of the April 29 issue that because of Collins, Murderers’ Row had been “extended to until it now covers the entire batting order.”26 A week later Collins warranted a two-column photo and profile article, again on the paper’s front page.27

He rolled along until July 20, when he injured his throwing arm in a collision with Wally Schang of the Browns that knocked him out of the game. He was replaced by Bill Skiff, essentially a bullpen catcher.28 Fourth-year man Benny Bengough had himself been limited by a sore arm all season. So when the Washington Senators placed Severeid (by then 35) on waivers, Huggins and Barrow snapped up the veteran on July 22. Collins only pinch hit twice until August 11 and started just 11 more games after the July 20 injury.29 Huggins used Severeid as his most frequent starter after his arrival. And when Collins did get a start, as he did against the White Sox in a rain-shortened game at Yankee Stadium on August 17, the sore arm didn’t help; he allowed six stolen bases in five innings, including a steal of home by Bill Hunnefield on Collins’s throwing error attempting to catch Willie Kamm’s steal of second base. “It got so that [Yankee center fielder Ben] Paschal would begin running toward the fence every time the pitcher delivered the ball with a man on first.”30

The Yankees came back from their disastrous 1925 finish to win the 1926 pennant by 3½ games over the Indians. Despite his woes after the arm injury, Collins finished the season at .286 in 290 at bats with 73 walks that pushed his on-base percentage to .433.31 He had started 93 games during the regular season, but Severeid—the mid-season waiver acquisition—started every game of the Yankees’ seven-game World Series loss to the St. Louis Cardinals. Collins mopped up in three games, batting twice without reaching base. He did, though, nearly double his $6,000 salary with a $5,584.51 winners’ share from the Series gate receipts.32

Huggins and Barrow went into action again on the catching front during the 1926-27 offseason. On January 13, 1927, they traded infielder Aaron Ward to the White Sox for 27-year-old backstop Johnny Grabowski. Ten days later they released Severeid, intending to use Bengough, Collins, and Grabowski as a platoon.33 Bengough had the highest salary of the trio (at $8,000 to Collins’s $7,000 and Grabowski’s $5,500), but Collins once again had the most starts: 74 to Grabowski’s 56 and Bengough’s 25. He produced another solid year at the plate, hitting .275 with seven home runs, 36 RBIs and a .407 on-base percentage fueled by 54 walks (against only 24 strikeouts). The 1927 Yankees—broadly recognized as among the finest in baseball history—sailed to a 110-44 record, winning the pennant by 18½ games. The team was a heavy favorite over the National League champion Pittsburgh Pirates (winners of a less imposing 94 games) and rolled into Forbes Field to open the World Series on October 5.

Collins caught that first game, in which New York nipped the Pirates, 5-4. He then gave way to Bengough and Grabowski in the next two games, both Yankee wins, but was back behind the plate for Game Four on October 8 in Yankee Stadium. He turned in a 3-for-4 day with a double and a walk. Although the Pirates had kept things relatively close throughout the Series, the Yankees won again, 4-3, to sweep.

Collins’s .600 average in two Series games didn’t draw much attention from the press, but it topped Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and the rest of the Yankees. It also had to be satisfying for a player who had been thought unworthy of the majors by the fourth-place Browns after the 1924 season. Back home in Kansas City, his Series performance earned Collins a surprise tribute party on October 17.34 And his 1927 World Series share, even with fewer games funding the pool than in 1926, was slightly higher, at $5,782.24.35

The Yankees used the same catching rotation in 1928, but Grabowski had 59 starts to Bengough’s 50 and Collins’s 45. Collins didn’t hit much, batting .221 with 6 home runs and 14 RBIs; his on-base percentage even slid to .380. He didn’t start after September 7, partly because there was a fourth catcher now in the mix: 21-year-old Bill Dickey, a converted pitcher who ultimately hit and caught his way to the Hall of Fame. The rookie arrived from Class-A Little Rock on August 15.36 The Yankees won the pennant again and swept the Cardinals in the World Series, but Collins was an afterthought; in his only playing time, he caught the last three innings of the final game. In his one at bat, he hit a double—probably meaningless to anyone but him and maybe the home folks in Kansas City—off Grover Cleveland Alexander in the top of the ninth inning. But for the third time in three years he shared in the Yankees’ World Series bounty, this time for $5,813.20.37

The Yankees presciently saw Dickey as a long-term solution behind the plate.38 After three years as a Yankee, Collins, now 32, was once again surplus. New York sold him to the woebegone Boston Braves for the $7,500 waiver price on December 13, 1928.39 Collins, with an $8,000 contract, opened the 1929 season with the Braves. Owner-manager Judge Emil Fuchs even tabbed him as his Opening Day catcher against the Brooklyn Robins on April 18. Collins was hitless, but drove in a run with a sacrifice fly in the bottom of the third and drew a walk as the Braves rolled up an 11-4 lead after five innings, then held on to win, 13-12. Collins was back behind the plate for the first game of a doubleheader the next afternoon and drew a pair of walks. He left for a pinch runner in the seventh inning; Fuchs started 26-year-old second-year-man Al Spohrer behind the plate in the second game. Spohrer went 2-for-4 with two RBIs, continued to hit, and that was it for Collins as a frontliner, even with an eighth place club. He either spelled Spohrer in late innings or pinch hit in just four more games. He was gone after striking out against Carl Hubbell to end the Braves’ 11-2 loss to the Giants at the Polo Grounds on May 23.

The Braves demoted Collins to Double-A Buffalo, where he played sparingly for the rest of the 1929 season. In 1930 he moved on to 21 games with Seattle in the Pacific Coast League, then finished that season with somewhat of a flourish back home with the Kansas City Blues. There, he hit .358 in 44 games, then came back for two more seasons as a third-string catcher and pinch hitter. He left Organized Baseball after his 1932 season with the Blues.

In a workmanlike 10-year major league career brightened by three seasons with Yankee pennant clubs, Collins appeared in 543 games, hit .254 with 33 home runs, and drove in 168 runs. His ability to either get the bat on the ball or draw walks produced a career .378 on-base percentage and a 1.16 walks-to-strikeouts ratio.40 Defensively, he came closest to being an everyday catcher only in 1926 and 1927. His career catching statistics were middling: a .974 fielding average and a below-league-average (37% against 42%) caught-stealing rate.41

In 1936, Collins saw an opportunity to get back into baseball in the league where he had started as a professional. Minor league baseball in St. Joseph, Missouri, dated back to 1886. The St. Joseph Saints had been in and out of the Western League since its inception; from 1931 on, they had been perennial pennant and playoff contenders. But after winning the 1935 championship, owner Frank Haley abruptly announced that he was moving the club to Waterloo, Iowa. Collins and Van Hammer, a former minor league catcher, sought and were awarded the St. Joseph franchise for the 1936 season.42 The Depression was continuing to burden baseball, however, and when Western League officials couldn’t find an eighth team for 1936, St. Joseph was voted out.43 Hammer dropped quickly out of the picture; although Collins made overtures to the Class-C Western Association for 1936 membership, nothing developed.44 Baseball was dormant in St. Joseph that season.

The Western League reorganized for 1937 and once again included St. Joseph. Collins still held the rights to the franchise, but this time “a political fight” over renovation of the team’s ballpark “ruined plans.”45 A wandering Western League franchise that had closed out the 1936 season in Omaha faced financial challenges there; civic interests in Rock Island, Illinois, presented a proposal for a team, and Collins took his franchise to Rock Island. His 1937 Rock Island Islanders, with old friend Burwell both pitching and managing, made it to midseason, then ran out of money. The Western League itself folded at the end of the 1937 season, but came back in a new iteration for the 1939, 1940, and 1941 seasons before World War II intervened. By then, Collins had lost interest in being a minor league baseball mogul.

He turned to the tavern business in Kansas City. Several years in, Collins had upgraded the tavern into a private establishment known as the Lakeside Club. Business after World War II had been good—but bookkeeping lax. In April 1952 the forerunner of the federal Internal Revenue Service46 filed nearly $40,000 in liens for alleged unpaid income tax from 1946 through 1950 against Collins, by then 56 years old.47 Pretrial wrangling with the prosecution reduced the ensuing criminal charges to three counts, but Collins was convicted of tax evasion on the 1946 count on December 2, 1952. On appeal, he was granted a new trial based on testimony that a friend had deposited $48,300 in a safe deposit box for Collins in 1944.48 There was no further trial; negotiations throughout 1953 ultimately resulted in dismissal of the 1946 count in December.

The Kansas City Star reported, “The portly ex-teammate of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig accepted the decision with the same grim lack of emotion he displayed last December when a jury acquitted him of one count and found him guilty of another [as] tears glistened in the eyes of his wife, Mrs. Daisy Collins.” It went on to relate how “Collins said that he had always maintained his innocence, charging that the government, in effect, had overlooked many details of his financial worth before 1945.”49

The Star’s account closed with Collins’s statement. “They took away my life’s work before 1945 and practically threw it out the window.” 50

Collins remained on the local baseball scene. In 1951, he became one of the first members elected to the Kansas City Baseball Hall of Fame.51 He made the usual rounds of sports banquets, raising some hackles in 1958 when he “took a dim view of any comparison between Mickey Mantle and [Babe] Ruth,” saying, “Nobody, I mean nobody, ever hit the ball as far as Ruth used to hit it. I’m not taking anything away from Mantle. He’s great. But he can’t compare to Ruth.”52 But when the Philadelphia A’s moved to Kansas City for the 1955 season, Collins didn’t hesitate to follow the newer era of players.

He continued to operate the Lakeside Club, “a meeting place for many former baseball players living in the Kansas City area,”53 until two heart attacks in 1959 forced him to retire. He still attended most of the A’s home games, and had been at Municipal Stadium on Thursday night, May 19, 1960, to watch the last-place A’s slip past the second-place Baltimore Orioles, 7-4, with a five-run rally in the eighth inning.54

The next morning, he did not answer Daisy, his wife of 42 years, when she attempted to wake him. Although he had been under treatment for his heart condition, Collins reportedly had made no complaint of feeling ill during the ballgame the night before.”55

Collins was 63 when he died. He was survived by Daisy and both of his sisters. He is interred in Memorial Park Cemetery in Kansas City, Kansas.

Sources and acknowledgments

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, I used the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for box scores, player, season, and team logs, and other information and the Family Search.org website for genealogical data. I also consulted Google Books.com and Newspapers.com for access to published material. SABR colleague Kevin Larkin and Cassidy Lent at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Giamatti Research Center in Cooperstown, New York, provided me with details from Pat Collins’s file.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Collins’s birth, draft registration, and death records, as well as his listings in Baseball-Reference, Retrosheet, and the tenth edition (1996) of the Baseball Encyclopedia, all document his name as Tharon Patrick Collins. But 22 years after Collins’s death, some question apparently remained in the mind of Cliff Kachline, one of SABR’s founding members and its first executive director, as to Collins’s exact name. On January 12, 1982, Kachline, then the official historian for the Baseball Hall of Fame, wrote to Collins’s widow requesting clarification on his middle name—asking her to note it on his letter and return it. Mrs. Collins, did, reporting the middle name “Leslie.” Copy of letter dated January 12, 1982, from Clifford Kachline to Mrs. Tharon P. (Daisy C.) Collins, with Mrs. Collins’s printed reply. Pat Collins file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Giamatti Research Center, Cooperstown, New York, hereinafter styled “Pat Collins file.”

2 Over the years Sweet Springs has grown little. The 2010 US Census reported the population as just under 1,500.

3 There’s no indication that Collins had two middle names—and the “Patrick” and “Pat” nickname might have come from the tendency to call many young Irishmen “Pat” in the early 20th century—but there is no question that Collins was known as Pat Collins throughout his lifetime.

4 Julius, however, is not reported to have died until 1933. Perhaps Sarah’s “widow” designation in 1910 was simply a matter of self-reporting for a woman with four dependent children who may not have had any idea where her husband, the father of the children, might have been.

5 Leo Trachtenberg, The Wonder Team: The True Story of the Incomparable 1927 New York Yankees (Bowling Green, Ohio: Popular Press, 1995), 155; “Mack Wheat to Return,” Kansas City Kansan, February 6, 1921: 14.

6 Unattributed and undated clipping from Pat Collins file.

7 Joplin is located 160 miles south of Kansas City, on the outer fringe of the Ozark Mountains.

8 When, in an August 3, 1917, game at Joplin, visiting Omaha manager W. A. “Pa” Rourke clashed with the home plate umpire, catcher Collins aided the arbiter’s cause by landing a knockdown swing on Rourke’s jaw. Sympathetic Joplin police “interfered and led Rourke from the field, later arresting and taking the Omaha manager to central police station in the patrol wagon.” “Omaha Sweeps Series; Rourke Goes to Jail,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Star, August 3, 1917: 9; Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln), August 10, 1917: 3.

9 “Wuffli and Collins Get Credit,” Topeka (Kansas) Daily Capital, May 9, 1918: 3. “Collins announced that he purchased liberty bonds with the money.” It was quite a haul. That $63.00 would be worth $1,085.94 in 2020 dollars.

10 “Navy Team Winner In Good Game Here,” St. Joseph (Missouri) News-Press/Gazette, September 1, 1918: 10. St. Joseph is located about 55 miles from Kansas City.

11 “$6,000 For Joplin Players,” St. Joseph (Missouri) News-Press/Gazette, August 25, 1919: 10. The 29-year-old Mapel had a brief and unsuccessful major league career. He started three games and appeared in another for the 1919 Browns with an 0-3 record and a 4.50 ERA. He didn’t make the club in 1920, then disappeared from Organized Baseball until 1929, when he was 2-7 with the Class-AA Louisville Colonels at the age of 39.

12 Sothoren was 20-12 for the 1919 Browns as the club finished 67-72, tied for fifth place in the American League, 20½ games behind the soon-to-be-disgraced White Sox.

13 Schacht pitched for three seasons in the majors, but became more famous as “the First Clown Prince of Baseball.” Ralph Berger, “Al Schacht,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org, accessed November 3, 2020.

14 St. Louis Star and Times, September 27, 1919: 10.

15 “Pat Collins Wins Job,” St. Louis Star and Times, February 17, 1920: 16.

16 “Strong, Collins Want Bush League Jobs,” St. Louis Star and Times, March 30, 1920: 22.

17 “Collins Gets Series Slice,” Kansas City Kansan, November 11, 1921: 20.

18 Sisler was a large factor in the Browns’ 1922 run. He hit slashed .420/467/594 with 105 RBIs and was the American League MVP.

19 Hal Lebovitz, “Ask The Referee” column clipping from an undesignated newspaper, date-stamped June 21, 1982, in Pat Collins file. The Browns were at Philadelphia. St. Louis’s Homer Ezzell hit a two-run single in the second inning but immediately had a “call of nature.” To avoid delay, Philadelphia manager Connie Mack permitted the plodding Collins to serve as Ezzell’s courtesy runner under rules in effect at the time. Collins ultimately navigated to third base but was left stranded there; at the end of the inning, Ezzell returned to his defensive position and Collins returned to the St. Louis bench. Then in the ninth inning, Collins pinch-hit and drew a walk—only to be replaced by a pinch-runner, Cedric Durst.

20 “Pat Collins Toiling for a Job,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 1, 1924: 12.

21 “Pat Collins Is Traded Off By St. Louis Browns,” Joplin (Missouri) Globe, January 4, 1925: 8. Dixon became the Browns’ primary catcher in 1925 after Severeid was traded to the Washington Senators in June.

22 “Welcomes The Change,” Kansas City Star, January 4, 1925: 12.

23 The Yankees paid St. Paul $25,000 for the rights to sign Collins. Times-Tribune (Scranton, Pennsylvania), September 8, 1925: 23.

24 This was Ruth’s infamous “Bellyache Heard ‘Round the World season.” He reported to spring training at 256 pounds, was ill throughout the Yankees’ spring training exhibition season, and never really recovered. Allan Wood, “Babe Ruth,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org, accessed November 5, 2020.

25 “Work for Collins,” New York Daily News, January 24, 1926: 36.

26 Joe Vila, “Collins Wins Favor With Sticking,” The Sporting News, April 29, 1926: 1.

27 “Broadway Agrees With Him: Catcher Pat Collins,” The Sporting News, May 6, 1926: 1.

28 “Hank Severeid Qualifying as Nemesis for Pat Collins of the New York Club,” Dayton (Ohio) Herald, August 4, 1926: 21. The July 20 game was one of only six in which Skiff appeared in 1926.

29 The ailing right arm impacted Collins’s hitting as well as his defense. He hit only .216 after July 20 with two extra-base hits and three RBIs.

30 “Yankees Lose to Chisox in Five Innings,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, August 18, 1926: 11.

31 Collins’s .433 OBP was second only to Babe Ruth’s .516 American League-leading mark for the 1926 Yankees. Lou Gehrig finished at .420.

32 World Series Gate Receipts entry, Baseball Almanac.com, accessed November 3, 2020. Per inflation calculations, Collins’s 1926 combined salary and Series share of $11,584.51 would amount to $170,351.20 in 2020.

33 “Hank Severeid Gets His Unconditional Release From Yanks,” Brooklyn (New York) Citizen, January 23, 1927: 24.

34 “A ‘Surprise’ For Pat Collins,” Kansas City Times, October 18, 1927: 11.

35 World Series Gate Receipts entry. Collins’s 1927 salary and Series share totaled $12,782.24 ($191,204.68 in 2020)

36 Frank Kearns, “Pennock and Dickey Form Poetry of Motion Battery,” Brooklyn (New York) Times Union, March 6, 1928: 61.

37 World Series Gate Receipts entry, Baseball Alamanc.com, accessed November 5, 2020. In three seasons with the Yankees, Collins aggregated $17,179.95 in winning World Series shares, worth about $261,500 in 2020.

38 And they were right. After three years of the three-man catching rotation, Dickey played 130 games and had 474 plate appearances for the 1929 Yankees. He went on to play 17 seasons, all with the Yankees, slashing .313/.382/.486, with 202 home runs and 1,209 RBIs for his major-league career.

39 “Collins to Braves,” Kansas City Times, December 14, 1928: 12. The 1928 Braves had finished 50-103 and in seventh place in the National League. They were about to embark on a 1929 season in which their owner, Judge Emil Fuchs, took over the managerial reins as a cost-saving measure. Fuchs’s team won six more games than the 1928 club, but dropped to eighth place in the 1929 National League standings.

40 Pat Collins statistical summary page, FanGraphs.com, accessed November 9, 2020. As a comparison with the current game, J.T. Realmuto, considered by many to be the best offensive catcher in baseball in 2020, has a 0.32 walks-to-strikeouts ratio through seven major league seasons.

41 By comparison, Hall of Fame catcher Gabby Hartnett (1922-41) and Collins played eight contemporaneous seasons, 1922-29. Over his 20-year career, Hartnett fielded .984 against a .978 league average. His caught-stealing rate was 56% against a league average 44%. And Severeid, who started ahead of Collins for five seasons in St. Louis and part of 1926 in New York, fielded .978 with a 43% rate for his career.

42 Ray Osborne, “Pat Collins Helps Save St. Joe,” The Sporting News, March 12, 1936: 6.

43 St. Joseph May Join Western Association,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 7, 1936: 16.

44 The Class-A Western League was listed No. 5 in the hierarchy of the 1936 minors. The Class-C Western Association was listed as No. 14. Both leagues played with six teams in 1936.

45 Leo Kautz, “Pat Collins Offers Team,” Davenport (Iowa) Daily Times, April 1, 1937: 24.

46 The former Bureau of Internal Revenue was renamed the Internal Revenue Service by the United States Treasury Department in August 1953.

47 “Tax Lien On Pat Collins,” Kansas City Star, April 1, 1952: 30.

48 “Pat Collins Granted New Trial in Income Tax Case,” Hartford (Connecticut) Courant, January 4, 1953: 43.

49 “Pat Collins Is Freed,” Kansas City Star, December 7, 1953: 1.

50 “Pat Collins Is Freed.”

51 Gil Smith, “In the Sportlight,” Leavenworth (Kansas) Times, August 6, 1953: 10.

52 Letter from reader Sherm Davis of Reserve, Kansas, in “What The Fans Are Saying,” Kansas City Times, June 26, 1958: 17. Ruth and Collins had occasionally roomed together on the road as Yankees. “Pat Collins Is Dead,” Kansas City Star, May 20, 1960: 36.

53 “Pat Collins Is Dead.”

54 And he probably empathized as he watched peripatetic A’s catcher Harry Chiti go hitless in five at bats and hit into a double play.

55 “Pat Collins Is Dead.”

Full Name

Tharon Leslie Collins

Born

September 13, 1896 at Sweet Springs, MO (USA)

Died

May 20, 1960 at Kansas City, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.