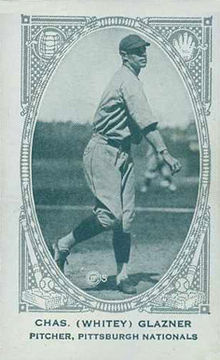

Whitey Glazner

A vital rookie starter for one of the best Pittsburgh Pirates rotations of all time, a PGA-caliber professional, and a recognized expert angler, the “Avondale Blossom” — Charley “Whitey” Glazner — was a talented and multifaceted sportsman in the truest sense of the word. Add in a veteran of the Great War, one who pitched nearly 18 innings in his very first ballgame back stateside, and you have a bona fide Southern legend on the diamond from days of yore.

A vital rookie starter for one of the best Pittsburgh Pirates rotations of all time, a PGA-caliber professional, and a recognized expert angler, the “Avondale Blossom” — Charley “Whitey” Glazner — was a talented and multifaceted sportsman in the truest sense of the word. Add in a veteran of the Great War, one who pitched nearly 18 innings in his very first ballgame back stateside, and you have a bona fide Southern legend on the diamond from days of yore.

Charles Franklin “Whitey” Glazner (born Glazener), was born on September 17, 1893, in Sycamore, Alabama, to John A. Glazener (1849-1921), a merchant and postmaster, and Annie (Anna) Linton Glazener (1856-1898). Charles and his twin sister, Ella May, were the 13th and 14th children for their father. Charley’s mother, Anna, died in 1898 when he was 5 years old, and his father soon remarried, to Katie A. Glazener (b. 1868), who helped raise young Charley. One of Charley’s brothers, William, eventually became superintendent of the DeKalb County (Alabama) school system.1 Another brother, also named John, became a long-tenured professor of geography at Jacksonville State University.2

Young Charley’s early years were spent in the Birmingham suburb of Avondale, where he was the sandlot star on the South Avondale squad, including one tilt against future South Atlantic League pitcher Smoky Bob Loveless.3 He also spent many an afternoon around the Birmingham YMCA and with the local Avondale Methodist Episcopal Church ball team. With Charley pitching for them, the Avondale M.E. team won the Sunday School pennant three years running and didn’t lose a single game for over two.4

Nineteen-year-old Glazner, all 5-feet-9 and 165 pounds of him, after pleading with manager Chic Hannon, was finally given a tryout with Anniston, Alabama, of the Class-D Georgia-Alabama League, where one 17-year-old named Tyrus Raymond Cobb had started his pro career nine years earlier. Glazner batted and threw right-handed with a pitching motion much like the underhand style of Carl Mays. On June 30, 1913, “the Birmingham YMCA youngster made good in a hurry, allowing only two scratch hits and only one ball (to go) out of the diamond” in a complete-game 3-1 victory against Opelika.5 Glazner wound up his first seven weeks of his professional career with a respectable 6-4 record.

He returned to Anniston for the entire 1914 season, drawing the second start on May 5 in a 5-0 home loss to Gadsden.6 He wrenched his back in a start at Selma on May 20,7 costing him nearly a month. On July 2 he shut out Gadsden 4-0 in seven innings in the second game of a doubleheader, protested by Steel Makers manager Appy “Sunset” Mills because it didn’t start at least two hours before sundown.8

However, the most memorable highlight from the season took place at Anniston on Independence Day, less than 48 hours later. Glazner relieved in the top of the third inning of a 5-5 tie in the first game of a doubleheader against the same Steel Makers and tossed seven innings of one-run ball. In the bottom of the fifth, the light-hitting hurler belted a surprising two-run homer to put Anniston up 7-6 on their way to a 10-6 win.9 After the four-bagger, some of the 1,300 Anniston faithful threw nickels, dimes, and quarters onto the field, giving Glazner “a purse of $29.32.”10

Three days later, the tagline read “Glazner Blanks Romans,”11 as young Charley tossed a four-hit shutout against Rome. The back gave out again on August 12 against LaGrange, requiring him to sit out the final two weeks of the season.12 Still, by the end of 1914, Glazner was considered “the best pitcher on the local club.”13 Charley was one of five league pitchers to make the year-end scribe-selected all-star team.14 The “premier hurler”15 in that quintet, Jakie May, was quickly scooped up by Memphis and then Detroit.

The Georgia-Alabama League did not keep any detailed pitching statistics for 1914. Even the Atlanta Constitution bemoaned not receiving updated statistics or correct standings from league President W.J. Boykin.16 Game-by-game box-score research shows Glazner accumulated a 7-8 pitching record (with one tie) over 147 innings in 20 games (18 starts), with 12 complete games including three shutouts, plus a couple of games in the outfield.17

In his third season in Anniston, Glazner made quite the impression, fashioning a 14-inning shutout on May 30, yet earning but a scoreless tie for his efforts.18 Later, on June 14, 1915, the “toe-headed ‘Whitney’ [sic] Glazner pitched himself to fame”19 for Anniston by winning both games of a home doubleheader against Rome, surrendering only four hits in the 7-1 opener and five in the 2-1 seven-inning sequel.

New York Yankees scout Bobby Gilks, on the lookout for “a couple of pitchers and a catcher,” made his way on June 29 to Anniston to take a look at Glazner, before moseying down the road the next day to Newnan to check out the Cowetas’ Jack Nabors.20

However, the league ERA champion for 1915 ended up being not Glazner, but a 16-year-old named William Harold Terry, future Hall of Famer Bill Terry. Pitching for Newnan, the future Giants first baseman great sported a 7-1 record to go along with a microscopic 0.60 ERA, the highlight of his campaign being a 2-0 no-hitter against Glazner and Anniston on June 30.21 Still, Glazner wound up leading the league with 101 strikeouts, and Nabors sporting the best record at 12-1. The Georgia-Alabama League finished its 60-game season on July 14, two days after Glazner had reported to Winston-Salem of the North Carolina State League.

Glazner won his debut for Winston-Salem over Raleigh on July 22, then was loaned to Red Springs in the short-season amateur Eastern North Carolina League, as the fifth-place Twins weren’t going anywhere. For Red Springs, Whitey beat Albemarle, 7-2, on August 23, in “the rottenest exhibition of baseball ever staged on the local grounds” featuring “errors and punk baseball.”22 Glazner was returned to Winston-Salem after less than a month at Red Springs. Pitching “star ball,” Glazner lost a 3-2 nailbiter in 10 innings to Asheville and eventual 27-game winner Doc Ferris on August 28.23 However, it was noted, regarding Glazner, that “the blond boy is among the best hurlers which the local grounds have housed” in 1915.24

Glazner spent the entire 1916 season back at Winston-Salem, posting a splendid 21-7 record (second in wins to the 23 by Charlotte’s Phil Redding) and a 2.20 ERA in 258 innings of work. His 21st victory occurred on August 29 over Asheville, 2-1, in a mere 31 minutes, the fastest minor-league game ever recorded.25

After his successful 1916 season, local expectations were sky-high heading into 1917, proclaiming that Glazner, “who created a sensation in the circuit last season by his pitching, will be back, which means twenty-five more wins for the Twins.”26

However, as the 1917 season dawned, Glazner did not intend on playing pro ball anymore. He planned on working full-time at his winter job as a machinist at the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company in Birmingham. Even Charles Clancy, the Winston-Salem manager, while penning a preseason team preview, stated that he had spoken with Glazner, who asserted “he has a good position at his home in Birmingham and is loathe [sic] to leave it.”27

Glazner held out for a spell, before finally signing on April 18.28 The “Birmingham phenom” shut out Raleigh 4-0 on April 28.29 Unfortunately, on the same road trip to Raleigh, he contracted poison oak, sidelining him for over a week.30 Then,on May 15, Glazner announced he was quitting professional ball to indeed go work at Tennessee Coal.31 The heartfelt homage penned by Winston-Salem Journal sportswriter Buck Campbell that day was quite moving:

Not only does the local club lose a winning pitcher, but professional baseball is also the loser as there are none too many players in the game of Whitey’s type. A modest, unassuming chap, with always a boost and never a knock. The writer has had the pleasure of a more or less intimate relation with him during the seasons he has been in the league, and it is with genuine regret that he learns that C.F. Glazner is leaving the professional game. He is one of the most popular players, not only here, but in the other cities, as well, and his host of friends wish him all possible success and hope that, should he desire to return to professional baseball, that this city will be fortunate enough to have him again. And to you, Whitey, may the world give you what you have given it — the very best that is in you.32

Glazner had impeccable timing; the North Carolina State League directors met two days later, on May 17, to discuss disbanding due to lack of interest owing to the United States’ entry into the World War,33 which they did on May 30.

Back in Anniston, Glazner began working at Tennessee Coal, but he wasn’t done playing ball, even for 1917. He ended up pitching regularly for Carl Landgrebe’s semipro Ensley Indians of the T.C.I. Manufacturing League, and among other achievements threw a no-hitter.34

Glazner had a change of heart as the 1918 season began, and auditioned with the local Class A Birmingham Barons of the Southern Association. As camp broke, he claimed the third slot in the Barons rotation, with manager Carleton Molesworth sending the “Birmingham Sand Lot Recruit to (the) Rubber”35 on April 21. Glazner struck out 13 in this first start, with no earned runs allowed, but “his fine slabbing work (went) for naught”36 in a 3-2 loss to Nashville. Still, the same writeup declared that “few rookie pitchers in the history of the (Southern) league have gotten away under such an auspicious start.”37

Glazner pitched in only six games for the Barons before his draft number came up. Barons management planned a “Whitey Glazner Day” to send him off in style.38 Glazner reported to Camp Sevier, South Carolina, on June 1, 1918.39 He returned after 13 months with the 321st Infantry of the 81st Division,40 as one of the last units to return stateside,41 having been sent into no-man’s-land, north of Bois de Manheulles in France, early on the morning of November 11, 1918, Armistice Day.42

Glazner was given his first postwar starting nod at home for Birmingham against Atlanta on July 15, 1919. It was a return for the ages. He pitched 17⅔ innings in the longest game ever at Rickwood Field, surrendering zero earned runs and 10 hits.43 Yet with all that, he still came up short, losing 6-5. These stateside heroics “cost Birmingham the services of Glazner for maybe the rest of the season, as he jerked a tendon in his right shoulder in the 18th, after having pitched 16 (out of the 17) frames of scoreless ball.”44 Glazner finally, “at this juncture of the hectic struggle had to leave the game, his right arm hanging limp at his side.”45 To make the present-day Pitcher Abuse Points adherents cringe even further, rain halted this memorable contest in the 10th inning for a half-hour, after which he was asked to crank it back up and return to the mound. There was no serious arm damage, and Glazner went on to notch a 4-5 record for the Barons to finish up 1919, his third consecutive truncated pro season.

Glazner got the call on Opening Day, April 14, 1920, for Birmingham, falling 5-2 to fellow Alabaman Shovel Hodge and Nashville, in front of a record 11,000 fans.46 He twirled a complete-game two-hitter on May 21 against Chattanooga, winning 2-1 in a crisp hour and 16 minutes.47 As of August 15, he had the best winning percentage in the Southern Association at 18-5 (.783). Not a bad hobby for someone whose listed occupation in the 1920 census read “helper in a pool hall.”48

On August 18 Glazner, along with fellow Barons hurler Johnny Morrison, was sold to the Pittsburgh Pirates, effective at the end of the Barons season.49 The next day, his 13-strikeout performance against Chattanooga was just one shy of Memphis’s Dazzy Vance league season high.50 He ended up with a 24-10 record the second-most wins ever for a Baron, two shy of the 26 victories for Carmen Hill in 1917 and teammate Morrison. He walked a league-high 101 batters, but his .706 winning percentage placed Glazner third behind Chief Yellowhorse (21-7, .750) of Little Rock and Cliff Markle (16-6, .727) of Atlanta.

On September 12 Glazner, along with fellow Barons Morrison, third baseman Clyde Barnhart, and outfielder Homer Summa, got the call to Pittsburgh, as skipper Molesworth sent more players to the majors than any other minor-league pilot that year.51 Graduating from the Southern Association, Glazner was hailed as “one of the greatest pitchers ever developed in that league.”52 He made his major-league debut on September 26 against Cincinnati, pitching five innings of relief, allowing two earned runs on five hits. His only other major-league appearance in 1920 was also against the Reds, on October 2, the last day of the season, in the last major-league tripleheader. Glazner surrendered one earned run in 3⅔ relief innings in the opener.

Back home in December after the season, Glazner married Estelle Mae Hersch (1895-1970),53 from nearby Bessemer in Jefferson County, the daughter of Austrian immigrants. Charles was 27, Mae three years his junior. They would have two children: Charles F. Glazner Jr., born in 1924, and Jewel Mae Glazner (Whitten), born a year later. Jewel eventually married and moved to Rhode Island, while Charles Jr. married, then later relocated to Florida.

Glazner reported to the Pirates’ spring-training facility in 1921 at least on manager George Gibson’s radar, as the skipper had “refused several good offers for the youth.”54 Glazner did win a relief role, and entered four April games for Pittsburgh, including a solid six-inning appearance on April 25, allowing the Pirates to come back and beat the St. Louis Cardinals in extra innings. That garnered Gibson’s trust enough to oblige him a start on May 2. Glazner’s first major-league start was successful: He beat Chicago, 4-3, in a complete-game effort, even while not recording a single strikeout. A Pittsburgh newspaper wrote that he looked like “a polished veteran,” and the Cubs “could not solve the tow-haired boy with any degree of skill.”55

Consecutive complete-game wins followed at home on May 7 against St. Louis, at Boston on May 12 (while driving in the go-ahead run), and at Philadelphia on May 17, giving young Glazner a 4-0 record to accompany his minuscule 1.27 ERA. By May 22 Pittsburgh was also on quite the roll, sitting at 25-6 and surprisingly 4½ games up on the New York Giants.

Glazner’s ERA climbed after two no-decisions but then he tossed his fifth complete-game victory on June 1 in a 4-2 verdict over the Cubs, belting a triple to boot. His “meteoric career in the majors” had taken flight.56 The rookie sported a 5-0 record and an ERA under 2.00 (1.98) one day into June. He became the first Pirates starter to begin his career with five straight wins (since matched by Zach Duke in 2005). Glazner finally proved mortal by losing on June 10, but proudly displayed a 9-1 record after a 13-inning complete-game win over the Boston Braves on July 22 in the second game of a doubleheader.

Four months into a big-league career, Glazner was ordained the “Pirates’ Best Bet,” one of the best heavers in the big show,”57 and “the darbiest slinger uncovered this semester.”58 The accolades kept coming: Glazner, “possessed of splendid control, a great change of pace, speed and a great assortment of twisters — all glorified with iron nerve and coolness — has whipped practically every team in the circuit, slung his way into the pitching leadership — and still goes merrily on in his efforts to pitching the Pirates to the baseball crest.”59

Glazner wound up his stellar 1921 rookie campaign with a 14-5 record, a 2.85 ERA, and 234 innings pitched for the surprising second-place Pirates. Pittsburgh actually led the NL by 7½ games on August 22, only to finish four back of McGraw’s World Series-winning Giants six weeks later.60 Glazner’s ERA trailed only those of Bill Doak of the Cardinals (2.59) and teammate Babe Adams (2.64) in the senior circuit. He led the NL with only 8.2 hits allowed per nine innings, and his .737 winning percentage tied teammate Adams for the NL lead. He surrendered but five home runs all season. Glazner was deemed “the pitching sensation of the 1921 crop of youngsters”61 and “the only real find.”62

Glazner helped form a stellar 1921 rotation alongside Wilbur Cooper (22-game winner, tied with Burleigh Grimes for the NL lead), Adams (12 years after his stellar 1909 three-win World Series performance), Earl Hamilton, and fellow rookie Morrison. A modern-day local Pittsburgh blog has ranked the 1921 rotation second best in Pirates history, eclipsed only by the 1902 staff.63 Also, one recent source ranked Glazner’s 1921 effort as the fourth-best rookie campaign in the entire decade of the 1920s, bested only by Wilcy Moore (1927), Dale Alexander (1929), and the brothers Waner (1926).64

Part of Glazner’s success was attributed to a plethora of three different deliveries: overhand, side-arm, and then underhand, like Carl Mays.65 He told a sportswriter:

I learned to pitch both overhand and underhand when I was with Birmingham. It’s a great help. I can throw a curve or slow ball from either overhand or underneath and by mixing in a few fast ones with the sidearm, it sort of keeps the batters guessing. Of course, the underhand ball is the hardest to control, but I worked on it until I have it down pat. I never tried to use it exclusively, like Carl Mays, for two reasons. The delivery is hard on the arm, and by throwing the same kind of ball both overhand and underhand the batter is mixed up.66

After the season Glazner headed back to Birmingham, wintering in the same community as the Giants’ World Series hero hurler Phil Douglas and another sparkling 1921 rookie, the Indians’ Joe Sewell.67

The next season, 1922, was much different. Glazner scuffled to an 11-12 mark with a 4.38 ERA, giving up 238 hits in 193 innings. About the most noteworthy item in Glazner’s 1922 season was that he served up two of Rogers Hornsby’s NL-record-breaking 42 home runs, on May 25 and June 9. His defeat by Cincinnati in the Pirates’ final game of the season on October 1 cost Pittsburgh second place and Glazner a .500 record.

Glazner started off rough in 1923 as well, getting punched around for seven runs (six earned) in his first start, on April 20, against the Chicago Cubs. His best Pittsburgh start of 1923 was his last, on May 19, a 5-0 shutout of Boston. Four days later he was traded, along with Cotton Tierney and $50,000, to the Philadelphia Phillies for Lee Meadows and Johnny Rawlings. Glazner pitched regularly for the Phillies in 1923, but produced only a 7-15 record in 23 starts, as Philadelphia finished in the cellar with a 50-104 mark. He also possessed one of the greatest home and road splits in major-league history. For 1923, he pitched only 54 innings at home, to an 8.00 ERA, and 137⅓ innings on the road, to a 3.54 ERA.68

By three games, the Phillies narrowly avoided the cellar again in 1924, improving only marginally to a 55-96 mark. Glazner was 7-16 for the season with an ERA just below six (5.92), with the Phillies posting an 8-27 record in games he pitched in. The vaunted Giants beat him five times, the most of any pitcher against one team in the league. Win or lose, at least manager Art Fletcher had his back. During a game on August 11 against Pittsburgh, Fletcher got into an actual fistfight with umpire Cy Pfirman after Glazner vehemently protested a call.69

Things got so bad that, from September 3 to 24, the floundering Phillies allowed five or more runs in 20 straight games (a dubious honor eventually matched by the 2017 Baltimore Orioles). During that stretch, Glazner posted an awful 13.17 ERA. His major-league run was screeching to a halt. Fletcher wasn’t about to let Glazner into the final two games at the Polo Grounds as the Giants finally clinched the NL pennant on the next-to-last day of the season. For Glazner, this was the last time he stepped foot in a major-league dugout as a player, thus accumulating a career 41-48 record, with a 4.21 ERA and 266 K’s in 783⅔ innings pitched.

Glazner spent the winter of 1924-25 golfing on occasion with Birmingham cronies including former Barons teammate Earl Whitehill of the Detroit Tigers, Col. Carl Landgrebe (Glazner’s old semipro manager), former White Sox pitcher and previous Nashville opponent Hodge, coach Lucius Ervin (former Drake University star, silver medalist in the pole vault at the 1919 Inter-Allied Games, and new athletic director of the Birmingham Athletic Club), and, finally, Lovick Stephenson (former University of Alabama star halfback, World War I flier, and eventual Army major).70

Announcing that “pitcher Glazner is on the market,”71 the Phillies scrambled to unload their “headstrong”72 hurler to seek “as much going material as possible,”73 but there were no major-league takers. Glazner was eventually sold to the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League on February 17.74 Even before his regular-season PCL career began, Charley was pummeled by his old Pittsburgh teammates in an exhibition on April 5, giving up nine earned runs on nine hits in just two innings.75 Nevertheless, one of his highlights in 1925 for the Angels was winning, 5-2, in the rarefied Salt Lake City air on May 13 against the Bees and the dynamic duo of Lefty O’Doul and Tony Lazzeri.76 Glazner posted sub-.500 seasons in both 1925 and 1926 for Marty Krug’s squad, which won the PCL championship in 1926.

Glazner and family came back much closer to home when he was sold outright by Los Angeles to Mobile in February of 1927.77 One person not choked up about Glazner’s departure to Dixie was San Francisco Chronicle sportswriter Ed Hughes, who would get irritated when Glazner, in one of his stunts, would “stall out on the mound, thus making the batter overanxious.”78 Hughes said he’d “be glad when Whitey got out of the league.”79 Another West Coast scribe claimed that Glazner worked slower “than a seven-year itch.”80

In Mobile Whitey was under the direction of manager Milt Stock, fresh off a 14-year major-league career. On May 9 Glazner severely injured his ankle while sliding into first base, and was out for three weeks.81 He carded an under-.500 record at 12-16 in 1927 yet posted an ERA of only 3.40. In 1928 he shot off like a rocket for the Bears, with two straight shutouts,82 and ended with a 22-10 record for a “rather weak”83 Mobile team. He even batted over .250 (.269) for a whole season for the only time in his career, notching six doubles.

Glazner was the subject of offseason roster subterfuge after the 1928 season. The Washington Nationals bought his contract at the end of the season, only to almost immediately release him to Birmingham without as much as inviting him to Washington’s spring training.84 Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis ruled that Washington was doing the bidding of Birmingham to the detriment of other teams in the league, a “cover up” and an illegal practice. As such, the Barons were fined $27,000, the biggest fine ever imposed on a minor-league team up to that point, with Glazner and Jay Partridge (Atlanta) being ruled free agents.85 Glazner quickly agreed over the phone to sign with Dallas of the Texas League,86 following his Mobile skipper Stock,87 then received more bids for his services, including one allegedly from John McGraw himself.88 Glazner momentarily tried to wiggle out of his verbal agreement, before eventually signing with the Steers.

Glazner posted a 15-9 record with a sub-4.00 ERA for Dallas as the Steers, the first-half winners of the Texas League, topped second-half winner Wichita Falls to win the title. In Game Three, Glazner won 4-0, beating George Payne, who had won 28 games in the regular season for the Spudders.89 Dallas then faced off against Glazner’s hometown Birmingham, champion of the Southern League, in the 1929 Dixie Series. “Stock Pins Hopes on Whitey Glazner Today” was the headline before the pivotal Game Six on October 2,90 but Glazner and the Steers fell to the Barons, 7-5.91

Before the 1930 season, Glazner was traded by Dallas to the New Orleans Pelicans for former major leaguer Dave Danforth,92 On April 10 Glazner shut out his former Pirates team for six innings in an exhibition game in New Orleans.93 He drew the Opening Day start, facing Mobile’s Axel Lindstrom, who didn’t record an out, while Glazner went the whole way, winning 14-6.94 Glazner’s 1930 season was productive; he posted a 19-8 record (third-most wins in the league), with a 3.34 ERA in 267 innings.95 The Pelicans didn’t win the Southern Association flag in 1930, but they had the final hand in determining who did. On September 9 a combination of stalling from Glazner and manager Larry Gilbert, along with fans throwing cushions and pop bottles, one eventually hitting the plate umpire in the head, resulted in awarding a pennant-clinching forfeit to the visiting Memphis Chickasaws.96

Another Glazner cropped up in minor-league box scores in 1930: Leroy (L.R.) Glazner, Whitey’s nephew (his brother Sion’s oldest son).97 Leroy, just like Uncle Whitey, pitched for Anniston in the revamped Georgia-Alabama League before moving to the league’s Cedartown team in August during his only professional season. He compiled a combined 4-3 record and 5.72 ERA in 14 games, even throwing a one-hit shutout at Talladega on July 29.98

As for Whitey Glazner, in 1931, the blossom began to wilt. He was again penciled in as the Opening Day starter, but it was not a sharp final season. New Orleans sources claimed Glazner’s poor showing was due to his “worrying over his cut in salary.”99 Whitey lost his final professional start, on July 1 against Mobile, ceding five runs on nine hits in 3⅔ innings. On July 12, after 12 games (10 starts), Glazner was released by New Orleans, to make roster space for Luther “Lute” Roy.100 So Whitey Glazner drove home to Birmingham “to take a rest for the remainder of the season” … and become a golf pro.101

He quickly began taking dedicated lessons at his hometown Woodward Golf Club under the tutelage of pro Pete Grandison.102 Less than 12 months removed from the mound, Glazner surprisingly made the 1932 Montgomery Open match-play finals with a 19-hole win in the semifinals, only to lose handily to Birmingham attorney Files Crenshaw Jr., who was victorious for the fourth straight year.103 A week after Montgomery, Glazner made the finals of the Southern Amateur.104 He also would make the finals of the North Birmingham tourney with a 22-hole win in the semifinals.105 By October of 1933, Whitey qualified for the Southeast PGA Open tourney in Pensacola, along with Yankees outfielder Sammy Byrd, widely considered the best baseball player golfer, who finished sixth.

Still, Glazner didn’t stuff the leather into the attic just yet. He pitched semipro in 1933 for Pan-Am of the Dixie Amateur League,106 whose team took the first-half honors, before playing Elmore in the City League Championship in September. Glazner pitched all 14 innings, allowing two runs on 15 hits, in a win on July 1 vs. Prattville.

Glazner became the head pro at Woodward Golf Club, playing in the Southeast PGA Tournament multiple times, even getting a hole-in-one in 1935.107 Woodward, with Glazner as a co-host, held the second Birmingham Open in 1938. A year later, he tied for fifth in the Alabama State tourney played locally in Birmingham. The 1940 census lists Glazner as a golf-club caretaker. As of 1942, Glazner was still employed at Woodward Golf Club, then later at Roebuck Golf Club.

In early 1943 Glazner was named to writer Guy Butler’s second-team All-Time Southern Association squad (spanning 42 years), just behind Dazzy Vance, Burleigh Grimes, Earl Whitehill, Theo Breitenstein, and Harvey Coveleskie. On July 15, 1943, Glazner was voted into the inaugural class of the Birmingham Barons Hall of Fame, and was present at the ceremony alongside fellow inductees Eddie Wells and Yam Yaryan.108 In 1953 Glazner was named to the All-Time Alabama major-league baseball team for the first half of the twentieth century, alongside the likes of Rip Sewell, Early Wynn, and Virgil Trucks.109

In 1960 Glazner, “one of the greatest competitors the game has ever known,”110 joined Ed Stack at the Boswell Golf Course, agreeing to work three days a week, so as not to interfere with his fishing, as “he’s a top plugger.”111

Glazner’s wife, Mae died in 1970, after which he moved to the Orlando, Florida, area. The record shows he played in an AGO (Amateur Golfers of Orlando) tourney in 1976 at the spry age of 82.

In 1987 Glazner was flown to Pittsburgh to celebrate Pirates public-address announcer Art McKennan’s “passing of the guard,” as McKennan had actually served as a batboy from 1921 to 1923. Glazner was believed to be the oldest living Pirates player, 93 years old at the time.112

Glazner died in Orlando on June 6, 1989, at the age of 95. He was survived by his children, Charles Jr. and Jewel, as well as four grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.113

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Besides the sources listed in the Notes, Baseball-Reference.com was the primary source of statistical information for this biography.

Also utilized were MyHeritage.com for birth, death, and marriage records and

US Census Records.

Notes

1 Alabama Journal (Montgomery), January 16, 1960: 8.

2 Teacola (Jacksonville, Florida), December 12, 1939: 4.

3 Frank McGowan, “Smoky Bob Could Throw,” Birmingham News, January 7, 1953: 13.

4 “Wonderful Record of Amateur Team,” Birmingham News, June 1, 1913: 9.

5 “Anniston 3, Opelika 1,” Atlanta Constitution, July 1, 1913: 11.

6 Birmingham News, May 6, 1914: 10.

7 Anniston (Alabama) News, May 21, 1914: 2.

8 Montgomery Advertiser, July 3, 1914: 9. The protest was rejected.

9 Anniston Star, July 5, 1914: 7. For another unlikely pitcher home run on July 4, see: sabr.org/gamesproj/game/july-4-1985-fireworks-and-rain-mets-braves-engage-in-a-holiday-epic/

10 “Anniston’s Fourth Quiet” Anniston Star, July 5, 1914: 7.

11 Anniston Star, July 8, 1914: 9.

12 “GAL Update,” Chattanooga Daily Times, August 24, 1914: 8.

13 Chattanooga Daily Times, August 24, 1914: 8. Glazner with one “e” was now the accepted spelling.

14 Carey J. Ayers, “Sport Writer of Star Picks an All-Star Team,” Anniston Star, August 26, 1914: 6.

15 Anniston Star, July 28, 1914: 6.

16 Atlanta Constitution, June 2, 1914: 8.

17 Whitey Glazner’s 1914 Anniston Moulders Pitching Statistics: 20 G 18 GS 12 CG 7-8 W-L 147 IP 127 H 68 R 43 ER* 38 BB 92 SO. *Based on at least 39 errors committed behind Glazner and the number of runs scored in each inning, the author estimated the number of earned runs for each game. In this case, the estimate totaled 43 earned runs, which would have given Glazner an ERA of 2.63. Ran Killingsworth (13-11) and Cecil Batson (10-16) were the two front-line starters for the Moulders in 1914. Baseball Reference lists Glazner with 22 appearances.

18 Anniston Star, June 30, 1915: 2

19 “Anniston Wins Two,” Atlanta Constitution, June 15, 1915: 11.

20 “Gilks Looking Over Ga.-Ala. Players,” Atlanta Constitution, June 30, 1915: 11.

21 Anniston Star, July 1, 1915: 10. See also Robert C. McConnell, “Bill Terry as Pitcher,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, 1989, https://research.sabr.org/journals/bill-terry-as-pitcher.

22 Charlotte Observer, August 24, 1915: 3.

23 Greensboro Daily News, August 29, 1925: 6.

24 “’Slats’ Ledbetter Was Too Much for Twins,” Twin-City Daily Sentinel (Winston-Salem, North Carolina), September 4, 1915: 9.

25 “Season’s Prize Farce Is Staged in Asheville,” Twin-City Daily Sentinel, August 30, 1916: 8.

26 Twin-City Daily Sentinel, March 5, 1917: 8.

27 “Clancy Tells Fans How Good Twins Look to Him,” Twin-City Daily Sentinel, March 31, 1917: 16.

28 “Whitey Glazner Has Signed His Contract,” Asheville Citizen-Times, April 18, 1917: 2.

29 Asheville Citizen-Times, April 29, 1917: 17.

30 “Manager Clancy Is Hit Hard Hit Again,” Twin-City Daily Sentinel, May 3, 1917: 7.

31 “Whitey Glazner Quits,” Winston-Salem Journal, May 15, 1917: 6.

32 “Whitey Glazner Quits.”

33 Wisconsin State Journal (Madison), May 17, 1917: 8.

34 “Colonel Langrebe Has Three Stars in Husky Ensley Indians Pictured Below,” Birmingham News, July 23, 1917: 5.

35 Blinkey Horn, “Vols and Barons Idle While Rain Falls; One Game Today,” Tennessean (Nashville), April 21, 1918: 13.

36 “Glazner’s Fine Slabbing Work Goes for Naught,” Birmingham News, April 22, 1918: 5.

37 “Glazner Pitches Masterful Ball Against Pels,” Birmingham News, April 27, 1918: 5.

38 Birmingham News, May 19, 1918: 13.

39 “Barons to Lose Player,” Arkansas Democrat (Little Rock), May 17, 1918: 14.

40 Henry C. Vance, “Whitie Glazner Joins the Barons,” Birmingham News, June 28, 1919: 5.

41 Vance.

42 Palladium-Item (Richmond, Indiana), August 3, 1921: 9.

43 “Barons Win 18 Inning Game,” Pine Bluff (Arkansas) Daily Graphic, July 16, 1918: 5.

44 “Atlantans Nose One Over for Neat Eighteen-Inning Conquest of Birmingham,” Atlanta Constitution, July 16, 1919: 12.

45 Atlanta Constitution, July 16, 1919: 12.

46 Chattanooga Daily Times, April 15, 1920: 10.

47 Nashville Banner, May 22, 1920: 7.

48 US Census Bureau, 1920 Census.

49 Pittsburgh Daily Post, August 19, 1920: 8.

50 “New Orleans Leads in Pennant Race of Southern League,” Tuscaloosa News, August 22, 1920: 6.

51 “Molesworth Is Best Developer of Young Players in Minor Leagues,” Birmingham News September 19, 1920: 53.

52 Pittsburgh Daily Post, December 21, 1920: 12.

53 “Glazner-Hersch Marriage Ceremony,” Birmingham News, December 16, 1920: 20.

54 Pittsburgh Daily Post, December 21, 1920: 12.

55 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette May 3, 1921: 11.

56 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette June 2, 1921: 9

57 San Francisco Examiner, July 19, 1921: 14.

58 Frank G. Menke, “Pirates’ Twirler Is Pitching Club Toward Pennant Heights,” Richmond Palladium-Item, August 3, 1921: 9.

59 Menke.

60 See Lyle Spatz and Steve Steinberg, 1921: The Yankees, The Giants, & The Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010).

61 Robert Boyd, “Few Recruit Pitchers Made Good in Major Leagues This Year,” Arizona Daily Star (Tucson), September 1, 1921: 7.

62 Boyd.

63 Rum Bunter blog, August 7, 2015: https://rumbunter.com/2015/08/07/top-five-pittsburgh-pirates-rotations/5/.

64 The Top Rookies of the 1920s,” Hardball Times, December 13, 2013: https://tht.fangraphs.com/the-best-rookies-of-the-20s/.

65 “Glazner Uses Submarine,” Sacramento Star, December 29, 1921: 8.

66 Bob Dorman, “Three Way Pitching Makes Rookie Famous in Year,” Sacramento Star, September 23, 1921: 8.

67 Albany-Decatur Daily (Albany, Alabama), October 16, 1921: 2.

68 Tom Ruane “A Retro-Review of the 1920s,” https://retrosheet.org/Research/RuaneT/rev1920_art.htm#A1923.

69 “Philly Manager Punches Umpire,” Salt Lake Telegram, August 11, 1924: 1.

70 Zipp Newman, “Whitehill to Spend Off-Season Here Playing Golf and Handball With Pals,” Birmingham News, January 25, 1925: 47.

71 Evening Sun (Baltimore), January 16, 1925: 41.

72 Ithaca Journal, January 19, 1925: 11.

73 Ithaca Journal, January 19, 1925: 11.

74 “Glazner, the Avondale Blossom, Is No Longer a Major League Pitcher,” Birmingham Times, March 10, 1925: 16.

75 “Meadows Goes the Full Route,” Pottsville (Pennsylvania) Republican, April 4, 1925: 5.

76 Los Angeles Times, May 14, 1925: 12.

77 Bob Ray, “Angels Sell Whitey Glazner to Southern Association,” Los Angeles Times, February 8, 1927: 21.

78 Ray.

79 Ray.

80 “The Hour Glass,” Los Angeles Evening Express, July 6, 1925: 10.

81 “Glazner Out of Game,” Chattanooga Daily Times, May 10, 1927: 13.

82 Tampa Tribune, April 18, 1928: 12.

83 Flem R. Hall, “The Sport Tide,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 19, 1929: 10.

84 Birmingham News, December 7, 1928: 1.

85 Birmingham News, August 14, 1960: 52.

86 “Glazner Added to Dallas Steer Team,” Austin American-Statesman, March 18, 1929: 9.

87 “Glazner to Work for Stock Again,” Selma (Alabama) Times-Journal, March 19, 1929: 6.

88 Joe Carter, “Raspberries and Cream,” Shreveport Times, March 19, 1929: 13.

89 Fort Worth Star-Telegram, September 22, 1929: 26.

90 Austin American-Statesman October 2, 1929: 11.

91 Times Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia), October 3, 1929: 15.

92 “Get Up, Get Close-Up of Cats,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram April 8, 1930: 19.

93 Indiana (Pennsylvania) Gazette, April 12, 1930: 20.

94 Nashville Banner, April 16, 1930: 10.

95 Birmingham News, September 21, 1930: 8.

96 “Pelicans Forfeit Game to Memphis 9 to 0,” Huntsville (Alabama) Times, September 10, 1930: 7.

97 Anniston Star, July 9, 1930: 10.

98 M.F. Davis, “Whitey Glazner Hurls One-Hit Game as Nobles Win,” Anniston Star, July 30, 1930: 10.

99 Birmingham News, July 3, 1931: 7.

100 “Whitey Glazner Is Given Release,” Decatur (Alabama) Daily, July 14, 1931: 6.

101 Birmingham News, July 17, 1931: 15.

102 “Charles Glazner, at the Age of 36, Is Learning to Become a Golf Professional,” Birmingham News, August 14, 1931: 14.

103 “Invitation Champ Retains Crown in One-Sided Battle,” Montgomery Advertiser, June 5, 1932: 19.

104 “’Whitey’ Glazner, Ex-Major League Hero, Golfs for Fun,” Huntsville Times, June 24, 1932: 6.

105 Birmingham News, August 23, 1932: 6.

106 “Whitey Glazner Loses Close Tilt,” Montgomery Advertiser, May 21, 1933: 7.

107 “Whitey Glazner Gets Ace on 13th of West Course,” Birmingham News, August 9, 1935: 11.

108 Zipp Newman, “Dusting ’Em Off,” Birmingham News, July 15, 1943: 19.

109 “All-Time Alabama Major League Team,” Birmingham News, March 22, 1953: 50.

110 Birmingham News, February 25, 1960: 17.

111 Birmingham News, February 25, 1960: 17.

112 Pittsburgh Press April 11, 1987: 26.

113 Orlando Sentinel, June 8, 1989: 22.

Full Name

Charles Franklin Glazner

Born

September 17, 1893 at Sycamore, AL (USA)

Died

June 6, 1989 at Orlando, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.