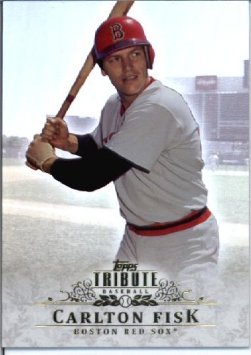

Carlton Fisk

Born in Bellows Falls, Vermont, on December 26, 1947, Carlton Fisk embodies traditional New England values like pride, ruggedness, and individuality. Those virtues were what the late Boston Red Sox public relations director Dick Bresciani was trying to capture in 1997 when he wrote that Fisk was a “native of Vermont” on his original plaque for the Red Sox Hall of Fame. But the greatest baseball player ever born in Vermont – and the man responsible for perhaps the most dramatic moment in New England sports history – doesn’t consider himself a Vermonter. Fisk grew up on the other side of the Connecticut River in Charlestown, New Hampshire, a town of less than 1,000 inhabitants – it just so happened that the nearest hospital was in Bellows Falls. So in a display of traditional New England stubbornness, Fisk insisted that his plaque be recast (at a cost of $3,000 to the Red Sox) to delete the Vermont reference and reflect that he was raised in New Hampshire.

Born in Bellows Falls, Vermont, on December 26, 1947, Carlton Fisk embodies traditional New England values like pride, ruggedness, and individuality. Those virtues were what the late Boston Red Sox public relations director Dick Bresciani was trying to capture in 1997 when he wrote that Fisk was a “native of Vermont” on his original plaque for the Red Sox Hall of Fame. But the greatest baseball player ever born in Vermont – and the man responsible for perhaps the most dramatic moment in New England sports history – doesn’t consider himself a Vermonter. Fisk grew up on the other side of the Connecticut River in Charlestown, New Hampshire, a town of less than 1,000 inhabitants – it just so happened that the nearest hospital was in Bellows Falls. So in a display of traditional New England stubbornness, Fisk insisted that his plaque be recast (at a cost of $3,000 to the Red Sox) to delete the Vermont reference and reflect that he was raised in New Hampshire.

In his first at-bat for the Bellows Falls American Legion team in 1965, Fisk crushed a home run at Cooperstown’s famous Doubleday Field, the site where according to myth baseball was supposedly invented. In ironic, storybook fashion, he returned to Cooperstown in 2000 for his induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Carlton Ernest Fisk inherited his extraordinary work ethic and athletic talent from his parents. Not only was his father, Cecil, an engineer in the tool and die industry in Springfield, Vermont, but Cecil’s second vocation was working the Fisk family farm. Often he would dismount from the tractor, race to a local tennis match to soundly defeat an opponent, and then return to the farm to resume his chores. In addition to playing tennis, Cecil also was a superb basketball player. Carlton’s mother, Leona, was famous in her own right as a champion candlepin bowler, and also excelled in softball and tennis. Certainly the gene for hand-eye coordination and the competitive drive ran deep in the Fisk family.

The Fisks of Charlestown represented an established athletic dynasty. Carlton’s older brother, Calvin, his younger brothers, Conrad and Cedric, and his sisters, Janet and June, all exhibited unusual athletic prowess. In fact, the son who was destined for the Hall of Fame was not considered the most talented of the progeny. Carlton was chubby as a youngster, which is how he acquired his well-known nickname, Pudge, or Pudgie. “If you saw him as an eighth-grader, you would not believe he could accomplish the things he has,” said Ralph Silva, his high-school coach.1 But Carlton was strong, and Coach Silva honed that strength by implementing weight training long before it became commonplace.

Beginning in 1962, when Calvin and Carlton first played Charlestown High School sports together, and continuing through 1972, when June graduated from the newly regionalized Fall Mountain School District, the Fisk family contingent could be counted on to lead their respective teams in annual postseason playoffs. Along with Calvin, Conrad, and younger brother Cedric, Carlton was part of the nucleus of a dominant Charlestown presence in basketball; baseball; and, when later introduced as a scholastic sport, soccer. Early on, though, Pudge’s greatest accomplishments came on the hardwood. Despite his 6-foot-2-inch frame, “Fisk could have made it in basketball,” said Coach Silva. “He was that tough.”2

After developing his hoop talent in his grandfather’s barn, Carlton went on to some legendary high-school performances. In a 1963 regional playoff game at the Boston Garden, Fisk made such an impression in a victory over the Winooski, Vermont, team that Walter Brown, owner of the Boston Celtics, leaned over to a local reporter and asked, “You have got to tell me – who is that kid?”3 In 1965, playing against Hopkinton in the New Hampshire Class M semifinals, the 6-foor-2 Fisk scored 42 points and yanked down 38 rebounds against an opposition front line that included players who were 6’10”, 6’8″, and 6’3″. When he fouled out with a minute left, Fisk received a standing ovation from the Portsmouth crowd, as Charlestown went on to lose by two points.4 An oft-told story is that after his son’s memorable performance, his dad Cecil’s only comment was that Carlton had missed four free throws.

But Cecil wasn’t being harsh or overbearing – he simply understood that to truly excel as an athlete, mental toughness was essential. Cecil’s philosophy on child-rearing was simple: “I expected them to do as well as they could, whatever they did.” Cecil and Leona Fisk sat behind the bench during basketball games but never said a word to Coach Silva, never criticized his strategy, and never let on if they disagreed with how their sons were coached. “No Hall of Famer ever had a better start than Fisk,” said Bellows Falls American Legion coach Tim Ryan, “and it was because of his parents.”5

Pudge’s baseball exploits began in the cornfields of his family’s farm. Learning the game together, he and his talented brothers would play for hours as time and chores permitted. The long and cold Northern New England winters reduced Carlton’s high-school baseball career, permitting no more than 17 organized games a season. In fact, the team’s early-season practices often began with Carlton and his teammates shoveling snow off the Charlestown High School baseball field, which was shaded from direct sunlight. Sometimes the team simply moved practice to the nearby Fisk cornfield. “I’d let them practice for as long as they wanted, long after we would have otherwise gone home,” said Coach Silva. “Of course, they don’t do that anymore.”6

Carlton was an intense athlete, and demanded that practice be taken seriously to mimic game-like conditions; on one occasion he punched out a teammate for “goofing off.” The competitive nature of those practices resulted in Carlton’s first experience as a catcher. During batting practice, with Carlton manning third base and Calvin behind the plate, a foul pop drew the attention of both of them. With the entire team yelling, “Fisk! Fisk! Fisk!” both attempted to make the catch; the resulting collision rearranged Calvin’s dental façade (only one of the two teeth retrieved could be saved). Because the catcher’s mask no longer fit over Calvin’s swollen jaw, the catching responsibilities fell to Carlton. (In typical Fisk fashion, Calvin played the next day, only in left field.)

Calvin, Carlton, and Conrad all pitched for the Charlestown team, which went 49-17 including playoff games during Carlton’s high-school career. One of those losses came in the Class M state championship against a strong Woodsville, New Hampshire, team. Despite striking out 14, Carlton was a victim of his own aggressiveness. With one out and the winning run on third, the Woodsville batter laid down a perfect squeeze bunt that hugged the third-base line. Not hearing his teammates’ cries of “Let it go foul!” Carlton leaped off the mound, picked up the ball, and threw across his body, making an amazing play to nail the batter at first as the winning run scored.

Because of the short high-school season, American Legion baseball takes on special importance in New England. Carlton played for Claremont in his first year of eligibility, but in 1965 he switched to Bellows Falls Post 5, coached by Tim Ryan, which had won the Vermont State Championship the previous year. In one game with Bellows Falls, so the story goes, Carlton was at the plate and behind in the count, fooled by two consecutive curveballs. When the catcher called for a fastball and was emphatically shaken off by the pitcher, the manager called time and approached the mound. “There’s no way I’m throwing him a fastball,” the hurler said. But the manager insisted that he throw what the catcher called for, and Fisk hit the next pitch (a fastball) on a line over the center-field fence. Another impressive home-run blast hit by Fisk in Bellows Falls cleared two outfield fences, and was for years marked by a simple white sign with an “X.”

Though he played in fewer than 100 games as an amateur, Fisk gained the attention of professional scouts. One thought he had potential but told Coach Ryan that his bat wasn’t quick enough – his power was mostly to right field. Ryan’s response was typically self-effacing: “He’ll get better coaches in the minors who can teach him to hit to left.”7 But despite his success in baseball (or, more accurately, his all-around athletic prowess, as he was named Charlestown High’s most valuable player in soccer and basketball as well), Carlton accepted a basketball scholarship to the University of New Hampshire.

The decision to attend UNH was made easier by the presence in Durham of his older brother, Calvin, who was captain of the soccer team and an All-Yankee Conference sweeper. But soon Calvin was drafted by both the Baltimore Orioles and the military (whose offer held more sway). He was 25 by the time he returned from Vietnam, too old (according to the Baltimore front office) to embark on a career in professional baseball. Carlton’s younger brother Conrad, considered the best pitcher of the Fisk clan, later signed with the Montreal Expos. Conrad was undefeated and threw a no-hitter in the playoffs during his senior year of high school, but an arm injury ended his career prematurely. Cedric, whose scholastic batting average was higher than that of any of his older brothers, didn’t pursue athletics beyond high school.

During the winter of 1965-66, Carlton led the UNH freshman basketball team to an undefeated season. While at UNH he also met his future wife, Linda Foust, a native of Manchester, New Hampshire. Then, in January 1967, the Boston Red Sox drafted him in the first round. Fisk was at first suspicious, believing that he was the token New Englander the Red Sox had taken to pacify local fans. He ended up signing mainly because he realized, as he told D.W. Roberts in a 1987 interview, “I could never be a six-foot-two power forward and play for the Celtics.”8

Carlton Fisk’s baseball career almost came to an end at Waterloo, Iowa, Boston’s entry-level team in the Class-A Midwest League. Despite batting .338 with 12 home runs in 62 games in 1968, he was despondent. Pudge’s letters home revealed that the source of most of his frustration was the team’s losing record. The Waterloo Hawks finished 53-60, 14 games behind the league-leading Cedar Rapids Cardinals. For Pudge, competition was personal combat – winning was the source of individual inspiration and satisfaction; losing was utterly unacceptable, intolerable, and humiliating.

But Fisk persisted and in September 1969 the Red Sox called him up to Boston from Double-A Pittsfield. The 21-year-old Fisk made his major-league debut in the first game of a doubleheader against the Baltimore Orioles on September 18. His cup of coffee turned somewhat bitter – in two games he went 0-for-5 with two strikeouts – and Red Sox beat writer Bill Liston wrote in the Herald-Traveler, “The word on Fisk is that he needs a year of Triple-A ball, especially to enable him to handle breaking pitches with the bat.”9

That year of Triple-A ball became one year with Double-A Pawtucket in 1970 and another with Triple-A Louisville in 1971; still Fisk remained upbeat and continued to improve. At Louisville his manager was Darrell Johnson, whom Fisk credited for making him a major leaguer. More than anyone else, Johnson taught Pudge how to be a leader, a field general for the team. Playing with abandon and all-out aggressiveness was one thing, channeling energy intelligently was another. “Johnson taught me to think about all the important facets of the catcher’s role, the things that help pitchers in various ways and those that let your teammates know you want to win,” he told an interviewer in 1973. Johnson also helped Fisk improve his hitting. “When I put the equipment on, my job is defense: to get the other team out, help the pitchers get the batters, help the fielders – to run the game,” Fisk said. “Once I take the equipment off, however, I stop thinking defense and start thinking offense.”10 That new concentration resulted in a .263 average at Louisville, 34 points higher than his average the previous season at Pawtucket.

Despite his excellent play (.313 with two home runs) in 14 games with Boston at the end of the 1971 season, Fisk was tagged as the third-string catcher for the Red Sox in 1972. The starter was Duane Josephson, who had batted .245 with 10 home runs in 1971 after coming to Boston in a trade with the White Sox; Bob Montgomery was the backup. But when Josephson was injured in the third game of the season Fisk was inserted into the Boston lineup as the starting catcher.

From the start, Carlton was a slugger. By June 13 the 24-year-old rookie had collected 32 hits, 20 for extra bases. His average was .278 and his slugging percentage was .574. His confidence rose with his slugging percentage, which stood at .629 by July 12, and he was beginning to attract attention. “Fisk is rapidly gaining the reputation of being the Johnny Bench of the American League,” wrote Larry Claflin,11 In July Orioles manager Earl Weaver selected him for the American League team in the All-Star Game. Fisk replaced Bill Freehan in the sixth inning, suddenly finding himself playing against Hank Aaron and Willie Mays, whose bubble-gum cards he’d collected back in Charlestown. For the 1972 season, Fisk caught 131 games and batted .293 with 22 home runs. His accomplishments earned him selection as the American League’s Rookie of the Year, the first player ever to receive the honor by a unanimous vote. He also won the Gold Glove for AL catchers and finished fourth in balloting for the AL’s Most Valuable Player. The Red Sox had fallen just a half-game short of the pennant. In a testament to the times, Pudge’s salary reportedly rose from $18,000 to $30,000, which, according to Claflin, was “as big a pay raise as any player in the game.”12

From the start, Carlton was a slugger. By June 13 the 24-year-old rookie had collected 32 hits, 20 for extra bases. His average was .278 and his slugging percentage was .574. His confidence rose with his slugging percentage, which stood at .629 by July 12, and he was beginning to attract attention. “Fisk is rapidly gaining the reputation of being the Johnny Bench of the American League,” wrote Larry Claflin,11 In July Orioles manager Earl Weaver selected him for the American League team in the All-Star Game. Fisk replaced Bill Freehan in the sixth inning, suddenly finding himself playing against Hank Aaron and Willie Mays, whose bubble-gum cards he’d collected back in Charlestown. For the 1972 season, Fisk caught 131 games and batted .293 with 22 home runs. His accomplishments earned him selection as the American League’s Rookie of the Year, the first player ever to receive the honor by a unanimous vote. He also won the Gold Glove for AL catchers and finished fourth in balloting for the AL’s Most Valuable Player. The Red Sox had fallen just a half-game short of the pennant. In a testament to the times, Pudge’s salary reportedly rose from $18,000 to $30,000, which, according to Claflin, was “as big a pay raise as any player in the game.”12

The Red Sox had been searching for a quality receiver ever since the Birdie Tebbetts/Sammy White era of 1947-59, trying such notables as Bob Tillman, “The Immortal” Joe Azcue, Tom Satriano, Russ Gibson, Mike Ryan, and others. In Fisk they finally had a tough, productive, intelligent, and dependable backstop with an unmatched desire to win. In fact often Pudge would even yell at his own pitchers to motivate them. He encouraged them to throw inside to the opposing batters, increasing his hurlers’ effectiveness, but it also served to escalate the intensity with the opposition. “If you play against him you hate him,” said manager Eddie Kasko, “but if you play with him and want to win, you love him. He plays as if he were on the Crusades.”13

Fisk’s tenacious aggressive style of play helped produced wins for the team but created minor skirmishes with the opposition. Collisions and run-ins with Thurman Munson, Alan Gallagher of the Angels, Frank Robinson, and the prickly Graig Nettles helped create a reputation as an unpopular player in the league. Emotion on the diamond seemed to define Fisk, in contrast with his New York rival, Munson. In a much-recounted incident with Munson, the two adversaries came to blows at Fenway Park on August 1, 1973. In the top of the ninth, with the score tied 2-2, Gene Michael whiffed on a suicide squeeze. Fisk elbowed the loitering Michael out of the way, and then took on Munson, who was bulldozing his way toward the plate. Fisk held on to the ball, but Munson continued to lie on top of Fisk to allow Felipe Alou to advance to second base. As Fisk pushed Munson off, Michael grabbed Fisk, who threw the scrawny Stick to the ground. Said Yankee manager Ralph Houk, “Fisk had his left arm right across Stick’s throat and wouldn’t let up. Michael couldn’t breathe. I had to crawl underneath the pile to try to pry Fisk’s arm off his throat to keep him from killing Stick. All the while he had Michael pinned down, he was punching Munson underneath the pile. I had no idea Fisk was that strong, but he was scary.”14

At times, Fisk’s on-field intensity would get him into trouble beyond the foul lines. At an autograph session in Springfield, Massachusetts, Fisk reportedly criticized teammates Carl Yastrzemski and Reggie Smith for not hustling and failing to show proper leadership. The outburst prompted a typical Red Sox intrasquad war of words, which Pudge eventually ended by explaining that he “never meant to say anything against them personally.” Even early on, for Pudge, perceived lack of hustle was blasphemous and inexcusable, and his comments were not out of character for someone whose desire to win as great as his.

In the 1973 season, the dreaded sophomore jinx caught up to Carlton Fisk in the second semester. Batting .303 on June 23, he hit only .228 in July, .198 in August, and .186 in September. He again caught 131 games for the Red Sox, who lost out to a surging Baltimore team at year end. Part of Carlton’s slide could be attributed to his desire to catch every game, which drains energy and reduces effectiveness. But the extended slump of 1973 was nothing compared to the challenges to come. At Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium on June 28, 1974, the Red Sox and Indians were deadlocked at 1-1 with two outs in the bottom of the ninth inning when George Hendrick drove the ball to the base of the left-center-field wall. Cleveland’s Leron Lee rounded third and crashed into the fully-extended Fisk, who was reaching for a high relay throw from Mario Guerrero. Pudge tore ligaments in his left knee. “My career was supposed to be over,” he recalled. “I was supposed to walk with a limp and have chronic back problems the rest of my life.”15

Fisk returned in 1975, and the long, lonely hours spent in rehabilitation made a lasting impression on him. Though for years the knee injury hampered his ability to throw out baserunners, he felt that it might have been a blessing. “In some ways, hurting my knee was one of the best things ever to happen to my offseason psyche,” Fisk said while still an active player. “Now, everything I do is programmed toward getting ready to play baseball. Before, winter was just a time to have fun hacking around the basketball court.”16 His obsession with conditioning was the secret to his 22-year career in the majors. Though injuries continued to plague him – in his career Fisk spent the equivalent of 5½-plus seasons on the disabled list – he always managed to return, allowing him to catch in 2,226 games, the most in major-league history until topped by Ivan Rodriguez in 2009. “More than the home runs, it’s the longevity that stands out as his greatest achievement,” said high school coach Silva.17

Injuries also taught Fisk another facet of the game, as he came to admire players like Jerry Remy, Rick Burleson, and Mike Flanagan, who faced serious career-threatening injuries and battled back, though not always successfully. He also came to fully respect the players who were perhaps not overly blessed with talent, but who made themselves successful through pain and hard work.18

Fisk’s return from the 1974 knee surgery was further delayed in 1975 when he was hit by a pitched ball in a spring-training game, breaking his forearm. Returning to a standing ovation on June 23, 1975, Pudge hit .331 over the remainder of the season to lead the Red Sox to the AL East title. Fisk batted .417 against the Oakland A’s in the League Championship Series, but his greatest heroics were yet to come.

Game Six of the 1975 World Series – a must-win game for the Boston Red Sox, down three games to two to the Cincinnati Reds – was a wild, seesaw affair. The Red Sox jumped out to a 3-0 lead on Fred Lynn’s three-run homer in the first inning, but the Reds came back and took a 6-3 lead into the bottom of the eighth, when Bernie Carbo’s pinch-hit, three-run homer tied the game. In the ninth inning, the Red Sox failed to score despite loading the bases with no outs, and the game headed into extra innings with the score knotted, 6-6.

It was 12:33 A.M. by the time Carlton Fisk stepped to the plate to lead off the bottom half of the 12th against Pat Darcy, the eighth Reds pitcher of the night. On Darcy’s second pitch, Fisk lofted a high shot down the left-field line. Millions of television viewers watched Fisk wave wildly as he made his way down the first-base line, willing the ball to stay fair. When it glanced off the foul pole – a fair ball – John Kiley, the Fenway Park organist, launched into Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus” as Fisk circled the bases in triumph. The home run touched off a celebration throughout New England. In the early-morning stillness of Charlestown, Dave Conant, a lifelong friend of Pudge’s, rang the bell of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, the Fisk family church, to celebrate the accomplishment of Charlestown’s native son.

Many consider Fisk’s game-winning blast the exclamation point on the greatest baseball game ever played. In Game Seven, however, Bill Lee couldn’t hold on to another 3-0 lead, and the Reds took the Series with a 4-3 victory. The Red Sox were once again denied their first World Series championship since the 1918 fall classic.

Fisk was named to the AL All-Star team seven times during his tenure in Boston. During one pennant race when his team was battling the Red Sox, Baltimore Orioles manager Earl Weaver said, “The guy they’d hate to lose most, even more than (Jim)Rice, is Fisk.”19 In determining Fisk’s importance, consider that in 1980 the Red Sox were 68-44 when he was behind the plate and 15-33 when he was not. Yet by 1981 Fisk was questioning whether the Red Sox front office really wanted him. Contract negotiations proceeded slowly, when then-general manager Haywood Sullivan blundered by failing to mail his contract on time, rendering Fisk a free agent. Despite his stellar years, including hitting .289 in 131 games in 1980, Fisk began to sense that the Red Sox front office thought he was expendable.

For Fisk the soured contract talks seemed like more evidence that the Red Sox management’s commitment to win had wavered. Boston had traded Burleson and Butch Hobson to California in December, followed by Fred Lynn in January, and the team was offering Fisk a contract renewal at less than market value. In Carlton’s mind, the effort to win extended beyond the players on the diamond, commitment to excellence was a top-brass requisite as well. Regarding contract renewals, negotiations to Fisk were simple. He’d performed for the Red Sox and performed well. So why should contract renewals be a battle? He felt estranged from the Boston organization.

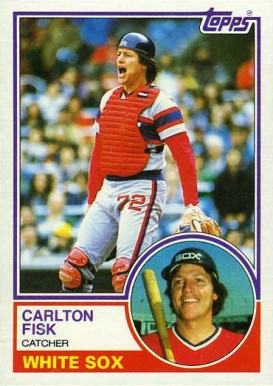

While the Red Sox offered the free agent Fisk a guaranteed $2 million plus incentives, the perennially noncontending but improving Chicago White Sox offered $3.5 million. For new owners Eddie Einhorn and Jerry Reinsdorf, Fisk’s acquisition would create instant credibility. Fisk made the decision to sign with Chicago. Nevertheless, the decision to leave Boston was difficult.

In 1983 the White Sox made their first appearance in the postseason since 1959, and many credited Fisk’s work with pitchers Britt Burns, LaMarr Hoyt, and Richard Dotson as the key. Pudge averaged 125 games for Chicago through 1985, when he hit 37 home runs with 107 RBIs. But that year his honeymoon with the White Sox front office ended with a bitter salary dispute, and subsequent re-signings in 1986, 1988, 1991, and 1993 were as smooth as Vermont dirt roads in mud season.

At an age when many former major-leaguer players are collecting well-earned pension benefits, and making appearances at card shows, fantasy camps, or old-timer’s games, Fisk continued his quest for personal goals. In August 1990, at age 42, he hit his 328th home run as a catcher, setting a major-league record. His son Casey was there. “I had goosebumps when he hugged his boy at home plate,” said White Sox manager Jeff Torborg. “That’s a big emotional thing right there. It meant so much to those two and that family.”20

In 1993 Fisk caught his 2,226th game, surpassing Bob Boone as the all-time leader. Then, on June 28, the White Sox released him. The next day, Carlton and Linda Fisk sent a simple but heartfelt message to the Boston faithful. They hired a plane to tow a banner reading, “IT ALL STARTED HERE. THANKS BOSTON FANS. PUDGE FISK.” They sent a similar message across the sky over Comiskey Park.21

Years have come and gone since Fisk last took command of the baseball diamond in 1993, but many specific memories of his playing days will not easily fade. The crucial game in Toronto late in September 1978, when the Red Sox were in the midst of staging their own comeback, winning 12 of their final 14 to force a playoff, serves as an example. In extra innings of a tie game, and playing with broken ribs, Fisk leaped out of his crouch, dove headfirst on the turf to corral a sacrifice-bunt attempt, jumped back to his feet, and fired a bullet to first to nail the runner. The play was instrumental in the eventual Red Sox win. (Fisk received the cracked ribs weeks before while diving over a fence to grab a foul popup.)

Another memory that will endure is the infamous double tag on the same play at the plate in Yankee Stadium in August 1985. Fisk, taking a relay from Ozzie Guillen, tagged out the barreling Bobby Meacham, then spun and tagged and crashed into Dale Berra, as the collision sent them both sprawling to the dirt. It was literally a bang-bang double play and preserved a seventh inning-3-3 tie, a match later won by the White Sox in extra innings.

Frequently criticized for pedantic play, Fisk with his slow, deliberate style could sometimes make a federal income-tax refund check seem speedy by comparison. Fisk was known as the vendors’ best friend. According to Dave Nightingale of The Sporting News, when he left Boston in the spring of 1981 the chief complainers were the Fenway concessionaires. “Several of them, you see, insisted that the Fiskless Red Sox were playing home games 20 minutes faster in 1981 and that the new brevity was costing them money at the concession stands.”22

And that Fisk home-run trot!! Hands held down, elbows stiff, head high as he rounded the bases in elegant, almost regal demeanor, the trot could be seen as arrogant to his opponents. “If you could only teach him to run differently, people wouldn’t dislike him,” said Milwaukee manager Del Crandall.23 But his teammates knew differently and saw it simply as a manifestation of Fisk’s own pride and respect for the game.

Said Roger Angell in his 1988 book, Season Ticket, “No catcher of our time looks more imperious than Carlton Fisk, and none, I think, has so impressed his style and mannerisms on our sporting consciousness: his cutoff, bib-sized chest protector above those elegant Doric legs; his ritual pause in the batter’s box to inspect the label on his upright bat before he steps in for good; the tipped back mask balanced on top of his head as he stalks to the mound to consult his pitcher; the glove held akimbo on his left hip during a pause in the game. He is six-three, with a long back, and when he comes straight up out of the chute to make a throw to second base, you sometimes have the notion that you’re watching an aluminum extension ladder stretching for the house eaves. …”24

Among the 13 Hall of Fame catchers for whom numbers are available (complete statistics don’t exist for Negro Leaguers Josh Gibson, Biz Mackey, or Louis Santop), Carlton Fisk ranks first in total games caught, at-bats, hits, runs scored, and doubles; second in total home runs and putouts; and third in RBIs; and is tied for fourth in fielding percentage. Fisk’s 128 stolen bases for modern Hall of Fame catchers are second only to Ray Schalk’s 176. He was an 11-time All-Star. The White Sox retired his number 72 in 1997, the same year he was elected to the Red Sox Hall of Fame. Fisk’s election to the Baseball Hall of Fame was almost a foregone conclusion, but it was made official in January 2000.

After some delay, Fisk provided the answer to a difficult question by announcing that he would wear a Red Sox cap into the Hall, even though he spent 13 years with the White Sox and only nine full seasons with the Red Sox. “I would like to say that this has always been my favorite hat, and I will be wearing this hat probably for the rest of my career,” said the man who worked at the time as a special assistant to Red Sox general manager Dan Duquette. At that same press conference, Duquette told a surprised Fisk that the team had decided to retire his number 27. “I didn’t think I met the criteria,” said Fisk. “It gives me goosebumps to think about it. I didn’t think it was at all possible.”25 In the past, the Red Sox had stated that they would retire a number only for a player who is in the Hall, spent at least 10 years with the team, and finished his career in Boston. Duquette, by hiring Fisk, ensured that he was finishing his career with the Red Sox. In formal ceremonies during 2005, the left-field foul pole was officially named the Fisk Pole.

Fisk is proud of attaining the success he enjoyed, and particularly so coming from a small town of under 1,000 people, with 43 in his graduating class, and playing less than 100 games as an amateur. And Fisk was never hesitant about showing his appreciation to the people he knew from the area. A favorite trick to get his attention before or after a game would be to yell, “Hey Charlestown!!” or “Hey, Pudgie!!” Carlton’s inevitable response would be to find the source, since that meant there was a native in the midst. Both his high-school coach, Ralph Silva, and Legion coach, Tim Ryan, have recounted that if Fisk knew they were in the stands, he would invite them and their families into the locker room to chat and meet the other players.

After being hired by Duquette in 1999, Fisk remained a Red Sox employee, doing promotional and marketing work for the team. He is considered to be a terrific baseball ambassador by the club. But aside from his appearances for the Red Sox, Carlton’s most important, enjoyable and rewarding role is being a grandfather. If fact if you were to ask Fisk about his proudest accomplishment, it would not involve baseball. To that question he once responded, “Probably to have a wife and kids who still call me ‘Dad’ and love me and kiss me when I’m going and kiss me when I’m coming.”26 Said Pam Kenn of the Red Sox, “He is the ultimate family man – he just adores his kids and grandkids.”27

Though Carlton Fisk will always be remembered for his dramatic home run in the 1975 Series, the incident that best defined how he played the game came on an otherwise unmemorable night in 1990 when Deion Sanders, then a rookie with the New York Yankees, failed to run out an infield popup. The next time “Neon Deion” came to the plate, the 42-year-old Fisk growled, “Listen to me, you piece of [recycled waste material]. Next time run it out.”28

Even though Sanders played for the opposition – and the hated Yankees at that – he’d violated the Fisk Code of Baseball Ethics. Thou shalt hustle. Thou shalt run it out. To Fisk, the proper way to play the game was always important – with passion, preparation, hard work, integrity, respect – and he constantly tried to inspire others to do the same. Traditional New England values, as taught him by his parents, were the source of Carlton Fisk’s motivation and the basis for his longevity and exceptional accomplishments. He acquired those values on the family farm in Charlestown, and they propelled him to Cooperstown.

Last revised: January 25, 2015.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited, the author also drew on materials provided by the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Notes

1 Interview with Ralph Silva, Claremont, New Hampshire, May 1998.

2 Ibid.

3 Interview with Ken Campbell, April 1998.

4 Manchester Union Leader, February 26, 1965.

5 Interview with Tim Ryan, April 1998.

6 Silva interview.

7 Ryan interview.

8 D.W. Roberts, New Hampshire Profiles, May 1987.

9 Bill Liston, Boston Herald Traveler, September 19, 1969.

10 Carlton Fisk with Lou Sabin, Boys Life, September 1973.

11 Larry Claflin, Boston Herald Traveler and Record American, July 14, 1972.

12 Larry Claflin, Boston Herald Traveler and Record American, November 25, 1972.

13 Peter Gammons, Boston Globe, December 8, 1973.

14 Ken Rappaport, Associated Press, August 2, 1973.

15 Roberts.

16 Bob Ryan, Boston Sunday Globe, January 22, 1978.

17 Silva interview.

18 Roberts.

19 Thomas Boswell, Washington Post, published in the Trenton Evening Times, July 2, 1978.

20 The National, August 10, 1990.

21 Nick Cafardo, Boston Globe, June 24, 1993.

22 Dave Nightingale, The Sporting News, May 17, 1993.

23 Peter Gammons, Boston Globe, July 13, 1974.

24 Roger Angell, Season Ticket (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1988), 40.

25 All quotations come from Larry Whiteside’s article in the Boston Globe, January 15, 2000.

26 Paul Ledewski, Inside Sports, August 1992.

27 Interview with Pam Kenn, Boston Red Sox, October 30, 2014.

28 Thomas Boswell, Washington Post, reprinted in Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 26, 1990.

Full Name

Carlton Ernest Fisk

Born

December 26, 1947 at Bellows Falls, VT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.