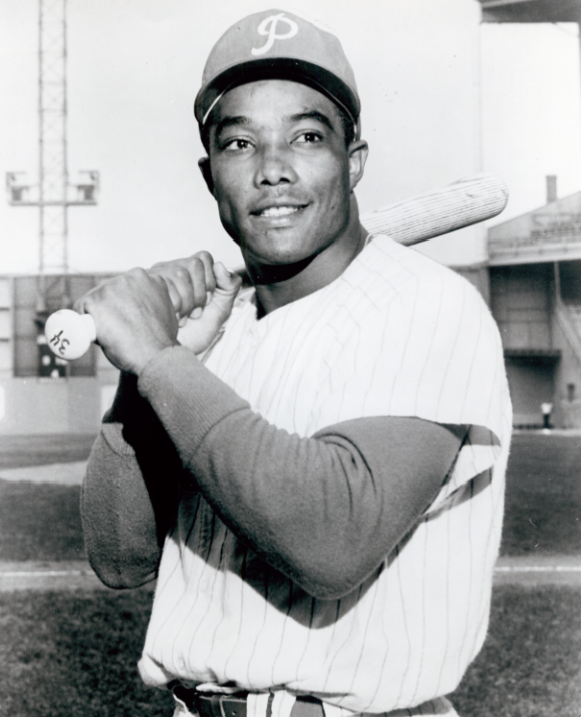

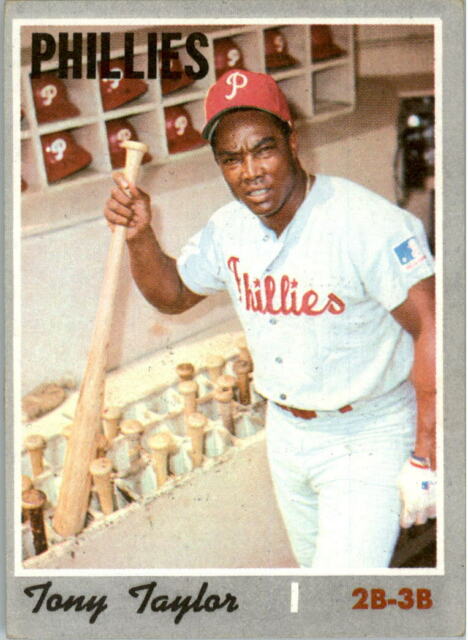

Tony Taylor

“They had a Tony Taylor Day in 1963 in Connie Mack Stadium, another in 1970 in Connie, and another Tony Taylor Day last year in Veterans Stadium,” said Antonio Nemesio Taylor Sánchez during spring training in 1976. “I must be doing something right. Right? There is this big love affair between the fans and Tony Taylor — a great honor, indeed, for me.”1

The Cuban “flashed a contagious grin” as he made that remark. Yet it wasn’t just his genial personality that made him one of the most popular players to wear a Phillies uniform. He was a very good second baseman who could handle various other positions. He was a respectable hitter who regularly ranked among the league leaders in stolen bases.2 Above all, he was a durable, hard-working presence. An Associated Press article summed Taylor up nicely in 1974: “For 11½ years before he was traded by the Phils to Detroit in 1971, Taylor put out, most of the time playing on bad teams. Regardless of the score or the standings, Taylor would come to bat, cross himself, kiss the tip of his bat in his inimitable style and give any pitcher a tough out.”3

Taylor returned to the Phillies as a free agent in late 1973, signing on his 38th birthday, and was on hand as the franchise returned to postseason play at last in 1976. Only Taylor and Dick Allen were members of both that team and the 1964 squad. After finishing his 19-year big-league career with 2,007 base hits, Tony went on to serve nearly three decades more as a coach and manager at various levels for the Phillies, the San Francisco Giants, and the Florida Marlins.

Tony Taylor was born on December 19, 1935. He had a younger brother named Jorge — who played 39 games in Class D for the Cincinnati Reds chain in 1960 — and a sister named Estrella.4 The Taylor family’s origins are intriguing. Previous versions of this biography, in the absence of solid information, speculated that the father might have been Jamaican, as is most often the case with Afro-Cubans who bear English surnames.5 In 2020, however, Jorge Taylor revealed that in fact his father came from Chicago, Illinois, to work in a Cuban sugar mill. He became known as Esteban, the Spanish version of Steven.6

Esteban Taylor’s wife was named Concepción Sánchez. Despite her Spanish surname, she was of Chinese descent, according to Jorge Taylor — her parents changed their family name upon arrival in Cuba, which received sizable numbers of immigrants from China.7 As baseball writer Andrés Pascual observed, in their homeland the Taylor brothers both had the nickname Chino.8 A number of Cuban pro ballplayers had some Chinese ancestry — but based on Jorge’s revelation, pending further research, Tony Taylor may well be the first man of any nationality with Chinese descent who played in the majors. Depending on how one interprets ethnicity, he could even be the first part-Asian to appear in a game at the top level.9

Taylor’s mother was significant in another way too. José Padilla, a teammate in Cuban winter ball who signed with Taylor, remembered that Tony was a devout Catholic. When Padilla asked Taylor why he always made the sign of the cross when coming to bat, the reply was that he did so in honor of and to remember Concepción.10

Taylor was born and grew up in Central Alava, located in Matanzas province. That’s in the western half of the island, to the east of the capital city, La Habana (Havana in English). The word central in Cuba often refers not to physical location but to a unique form of socio-economic enterprise that developed from the sugar industry. The eminent historian Hugh Thomas described it as “a powerful society within a society … concentrations of capital, technological and social organization, the product of union between several old large plantations, became known as a central, a centre of grinding linked with other plantations by rail and perhaps with the sea.”11

Young Antonio first played baseball at the age of 7 or 8.12 Central Alava was “a quiet place,” Taylor said in 1970. “Nothing to do but play ball or swim in the river.” His reminiscence continued, “As a boy I went to school and worked in my cousin’s butcher shop. I liked chemistry. If I didn’t go into baseball, I would have become a chemist for a sugar company.”13 Nicknamed Agüe14 (the meaning is uncertain), he graduated from Central Alava High School and played in his late teens for Estrellas de Colón in the Pedro Betancourt Amateur League.15 Based in Matanzas, this league was a stepping stone for young Cuban players from around the island. According to a 1960 feature by sportswriter Sam Lacy, however, Taylor’s parents were not keen on his pursuit of baseball and disciplined him.16

Taylor originally turned pro in 1954. A Cuban friend named Felix Gómez persuaded him to sign with Texas City, an independent team in the Evangeline League. In 1953 Gómez had played center field for that team.17 Originally a third baseman, Tony hit .314 in his first season. With his good speed, he led the league in triples with 12. Like many young Latino players of that era, however, he faced social, cultural, and linguistic obstacles off the field. “I had no one to talk to,” he said in 1970. “The only English word I knew was ‘Okay,’ and I would order meals by pointing at the food. In the middle of the season, the franchise was moved to Thibodaux in Louisiana, and that’s when I would have given up the whole deal, had I the money to get back to Cuba. I was so homesick. The fare to Havana was $72. I looked in my pocket, I had only $62. So I stayed.”18

Taylor first played in his homeland’s professional league during the winter of 1954-55. He went 2-for-8 in 12 games for Tigres del Marianao. The New York Giants then drafted Taylor into their organization. He played in 1955 for St. Cloud, which featured Bahamian shortstop André Rodgers and Leon “Daddy Wags” Wagner. His 10 triples and 38 steals led the Northern League, and he moved up to Danville in the Carolina League for 1956.

Before the winter of 1956-57, Marianao traded Taylor to Almendares, where he spent the remainder of his seven-season Cuban career. To Marianao went José Valdivielso, who was coming off his second season as a shortstop for the Washington Senators. At home, though, Almendares had Willy Miranda, whom many — including Taylor — viewed as the fanciest-fielding shortstop from Cuba — or anywhere. Though Taylor later had several slick double-play partners with the Phillies — including Rubén Amaro, Sr., Bobby Wine, and Larry Bowa — in 2006 he said of Miranda, “This guy was unbelievable.”19

Taylor advanced again to Dallas in the Texas League for 1957 (the year his father died). Though his average fell off to .217, he still won praise as “an excellent fielder and base-runner.”20 The Giants moved him up to the roster of Triple-A Minneapolis. Tony hit much more strongly in Cuba that winter. His manager with Almendares, Bobby Bragan, wanted the Cleveland Indians (who had named Bragan their manager right after the big-league season ended), to select Taylor in the minor-league draft that December. Instead, the Chicago Cubs took him just before Cleveland could.21

Taylor never played another day in the minors after 1957. He jumped straight from Double-A ball to the starting job as second baseman and leadoff hitter in Chicago in 1958. The Cubs’ main second baseman in 1957 had been veteran Bobby Morgan, but he hit only .207 and would play just one more game in the majors. Based on Taylor’s impressive spring training, manager Bob Scheffing was thinking of him as the new third baseman, another problem spot for the Cubs. However, he gave that job to Johnny Goryl (before the team acquired Alvin Dark in May).22

The Sporting News wrote, “The flashy Cuban had never played at the keystone position in his life. However, he tackled the assignment with determination and plenty of help and encouragement from [Ernie] Banks, his new roomie and sidekick.”23 The congenial “Mr. Cub,” still a shortstop in those days, befriended the rookie. As Taylor recalled in 1970, “When I first joined the Cubs, I was so lonesome that Ernie tried to talk Spanish with me. Good guy, Banks. Bad Spanish, but good guy.”24

As a rookie with the Cubs, Taylor hit a modest .235 with 6 homers and 27 RBIs in 140 games. He struck out 93 times, second most in the National League, though that total looks mild in the 21st century. However, Taylor’s 21 stolen bases ranked third in the league. Coaches Rogers Hornsby and George Myatt helped him with the conversion to second base, as did Chicago broadcaster Lou Boudreau. “He’ll make mistakes in the field,” said Bob Scheffing, “But he’ll get a lot of balls nobody else would reach.”25

During the winter of 1958-59, Taylor won the Cuban batting title with a mark of .303. Almendares (featuring Tom Lasorda and Sandy Amorós, among others) won the league championship and thus advanced to the Caribbean Series. In Caracas, Cuba won five of six games over Venezuela, Puerto Rico, and Panama. Taylor went 9-for-26 (.346) with a homer and four RBIs, also stealing three bases.

With the Cubs in 1959, Taylor’s batting improved to .280-8-38 in 150 games, and his 23 steals tied for second in the league. He also settled down on defense. Bob Scheffing told Sam Lacy in 1960, “Tony didn’t have time to break in. … That first season, he did everything wrong. … He messed up plays in the field, committed every kind of error imaginable and didn’t hit much either. … But he never gave up and had an excellent teacher in Banks, who was understanding, patient, and constantly working at keeping him loose. … Next year (1959) he became a big leaguer.”26

Also in 1960, Rogers Hornsby gave his views as a hitter about “the muscular Cuban, who has forearms like Popeye.” Hornsby said, “If he ever learns to stride into the ball and pull it, he’ll be a home-run slugger. He sort of falls away from the plate, but still he has so much power he hits a homer to right field occasionally.”27

Shortly thereafter, on May 13, 1960, Chicago traded Taylor and Cal Neeman to Philadelphia for Ed Bouchee and Don Cardwell. Phillies general manager John Quinn said, “We gave up two good players, but you can’t make a trade without giving up something of value, and we feel this trade was the best we could make. … We now have a fine second baseman in Taylor. He can hit, run, field, and is a fine leadoff man. Besides, he’s only 24 years old. The Phils have had a second-base problem for many years, but we have solved that for a long time to come.”28

Taylor, however, wept when he heard the news. “I felt uprooted again,” he said in 1970. “I had to leave behind my bride, Nilda, and she spoke no English.”29 Tony and Nilda Martínez were newlyweds; they had married that February 20.30 She was a sweetheart from school days who became a schoolteacher; they had met at a party in Cuba at a friend’s house.31

“It was tough breaking away from my dear friend Ernie Banks too,” Taylor added. Fortunately, however, there was a Cuban comrade in Philadelphia: first baseman Pancho Herrera, who helped him fit into the clubhouse. Tony and “Panchón” remained extremely close until Herrera died suddenly in 2005 — an event that also moved Taylor to tears. In fact, he cried like he had never done before in his life.32

Oddly enough, the Phillies had experimented with the big and bulky Herrera at second base in the spring of 1960. Taylor had quipped that runners were afraid to slide for fear that Panchón might fall on them. After the trade, though, the Phillies had gained a true second baseman. Taylor averaged 131 starts there per season from 1960 to 1964 (moving into a “supersub” role thereafter). He made the All-Star team for the only time in his career in 1960, playing in both games held that year and getting a hit in his only at-bat. In those days, Bill Mazeroski got most of the second-base honors in the National League. During the ten years from 1958 to 1967, future Hall of Famer Mazeroski won the Gold Glove eight times and was a seven-time All-Star.

The winter of 1960-61 was the last for professional baseball in Cuba; after that the Fidel Castro regime abolished the league. During his seven seasons at home, Taylor hit .275 in 409 games, with 26 homers and 158 RBIs. He led the league in triples three times and in steals once. The great Cuban pitcher Luis Tiant, whose pro career began in 1960, observed Taylor in the 1960-61 winter season while pitching for Habana, and they became friends for life. After Taylor died in 2020, Tiant called him, “A decent and well respected person (not only as a player) by those who knew him and played with him and against him. He was very serious and was focused on living a clean life and never known to be or cause any trouble.” Tiant saw Taylor as a great player who could field and hit and set a high standard for playing the game, and his many contributions placed the image of Cuban players at a very high level.33

Tony and Nilda left Cuba in 1961, when their baby daughter Elizabeth was just two months old. In 1975, he said, “We’d like to take the children back to Cuba just so Elizabeth could see where she was born.”34 The Taylors welcomed son Antonio Jr. about four years after Elizabeth.

Taylor’s big-league performance fell off in 1961. With the bat, he put up numbers of .250-2-26 in just 106 games, down from a combined .284-5-44 the year before. He also stole just 11 bases after tying for second in the NL with 26 in 1960; he had swiped more than 20 in each of his first three seasons. In 1964 he admitted to carrying too much weight in 1961. “That year I weighed 180 pounds. Now I weigh 166. Fourteen pounds makes a lot of difference. I learned something.”35 He spent the 1961-62 offseason in Philadelphia trimming down.

“I know we’re going to see a different Tony Taylor,” said manager Gene Mauch in spring training 1962. “I think he’s going to cover a lot more ground both ways this season.”36 He was seldom out of the lineup, except for a week in late June and early July when he kicked a stool after going 0-for-6 in a tough 12-inning loss at Candlestick Park in San Francisco. He finished the season with hitting marks of .259-7-43, and bounced back among the league leaders in steals with 20. Shortly afterward, on October 14, Tony joined an array of Cuban major and minor leaguers (including teammate Tony González) in a benefit game at Miami Stadium. The proceeds went to help Cuban refugees.37

In 1963 Taylor had a nice season with the bat (.281-5-49) and got MVP votes for the only time in his career. At the end of the season Gene Mauch said, “Bill Mazeroski wasn’t close to Taylor this year. Up ’til now I’ve said that Maz was the best. But you might have to underline was. This year, I know you’d have to underline was.” Teammate Cal McLish added, “You read a lot about guys like Pete Rose. People talk about Taylor like he was just another second baseman, instead of one of the best in the business.”38 That October 12 — playing third base and shortstop, though — Taylor represented the National League in the first and only Latino players’ game, held at the Polo Grounds.

Despite Gene Mauch’s penchant for platooning, Taylor remained a day-in, day-out regular in 1964. He started 148 games at second and fellow Cuban Cookie Rojas spelled him for the other 14. It wasn’t Taylor’s best year at the plate (.251-4-46), but he provided strong defense up the middle with Wine and Amaro. Considering that Rojas was a very good glove man, it said something about Tony’s value to the team. The diving stop on Jesse Gonder’s smash during Jim Bunning’s perfect game was, of course, Taylor’s own most memorable moment.

Taylor has had a good deal to say about the “Phillies Phold” over the years, but perhaps his most extensive public reflection came in 2004, when he spoke to the Bucks County Courier Times. He started by saying, “It’s still here. … We worked so hard, and to see it break so easy and the way it happened, it still hurts and I still cannot believe it. … Wherever you go, people remind you.” He added what a close team it was, though, then and 40 years later. Furthermore, he didn’t believe it was a choke, and gave Gene Mauch credit for trying everything to change the team’s luck. He concluded by saying, “I’m proud to be part of that team. It was a great team, a team that played to win. I can say now that in baseball, anything can happen.”39

Taylor remained the regular at second to start 1965, but after Don Cardwell hit him twice on the forearm with pitches on May 31, it opened the door for Cookie Rojas to play much more at his natural position. Taylor also suffered his worst year at bat, hitting just .229-3-27 in 106 games. Rojas continued as the primary second baseman in 1966, and Taylor saw duty at various other spots. Despite his fairly short stature (5-feet-9), he even started 43 games at first base in 1967, mostly when Bill White was injured in the early part of the season. He handled himself well there; Mauch and general manager John Quinn were glad they hadn’t traded him away previously (they never felt they got a good enough offer).40

Taylor returned to winter ball in the 1966-67 season. Starting in 1962-63, former Commissioner Ford Frick had prevented Latino ballplayers from going anywhere other than their home country in the winters — which hit Cubans particularly hard, since the Castro regime had done away with their league. Taylor said, “This is the best thing that has happened to me in quite a while. I couldn’t find anything to do before. All I did was stay home and watch television. That’s not good for me. I’m used to being active.”41

Commissioner William Eckert (with the help of his coordinator for Latin affairs, Cuban Bobby Maduro) overturned Frick’s edict in 1966. Taylor joined the San Juan Senadores of the Puerto Rican League. He won the batting title in Puerto Rico in 1967-68, edging José Pagán, .3418 to .3417. Tony credited the help of Roberto Clemente, his teammate with San Juan.42

In 1968 Taylor became a full-time third baseman for the first time in the majors after Dick Allen moved to left field. He switched back to his utility role in 1969. From 1966 through 1969, his offensive numbers were quite similar and subpar for him. He averaged 135 games played, 500 at-bats with a .248 average, 3 homers, and 36 RBIs. Yet in spring training 1970, manager Frank Lucchesi said, “Taylor is the most underrated player in the league. Every year he comes down here as an extra man and every year he winds up playing more games than anybody.”43

Not long before, during that same camp, “the biggest moment in my whole life” took place for Taylor — his mother, sister, brother-in-law, three nephews, and a niece arrived in Miami from Cuba. He had been trying to get them out since 1962, when his mother, Concepción, could have come but did not want to leave Tony’s sister, Estrella, behind. Tony commented, “They led a difficult life. They did not believe in the Communists and were not given food and clothing. They had to buy things in the black market.” The age of one nephew was an obstacle. “When a boy gets to be 14 in Cuba, they usually don’t let him out,” Taylor said, “because he goes into the army.”44

The Phillies had a new primary second baseman in 1970, Denny Doyle, who got the job after Cookie Rojas was traded to St. Louis. Taylor spelled Doyle and regular third baseman Don Money, also appearing in the outfield for the first time in the majors. He posted his best offensive season: .301-9-55 in 124 games — which caused some rumbles because the rookie Doyle hit just .208.

The Phillies had a new primary second baseman in 1970, Denny Doyle, who got the job after Cookie Rojas was traded to St. Louis. Taylor spelled Doyle and regular third baseman Don Money, also appearing in the outfield for the first time in the majors. He posted his best offensive season: .301-9-55 in 124 games — which caused some rumbles because the rookie Doyle hit just .208.

Yet Taylor saw little action in early 1971, and on June 12 Philadelphia traded the 34-year-old veteran to the Detroit Tigers for two minor-league pitchers, Carl Cavanaugh and Mike Fremuth. “I have nothing but praise for Tony Taylor,” said Frank Lucchesi. “But we’ve come up with a couple of pitching prospects and we are building.” Neither Cavanaugh nor Fremuth ever played a single game in the majors. Meanwhile, Taylor (who lived for many years in the Philly suburb of Yeadon) bade a tearful farewell. He said, “This is my home; I’ll die here.”45 A haunting photo also shows Taylor with a bat over his shoulder in the abandoned Connie Mack Stadium, which was overgrown with tall grass and weeds.

During his two-plus seasons of part-time duty in Detroit, Taylor hit .269 with 9 homers and 63 RBIs in 217 games. He hit .303 for the 1972 Tigers, winners of the American League East, and made his only postseason playing appearance that fall. In the loss to the Oakland A’s, Tony was 2-for-15 (.133) in four games.

Billy Martin, who managed Taylor in Detroit until he was fired in September 1973, wasn’t every ballplayer’s cup of tea — but Taylor liked him. In 1974, he said that Martin had treated him like a man and that he was proud of having played 2½ years for Billy. Tony said, “He gives 100 percent for his players.”46 The feeling was probably mutual, because Martin loved players — Venezuelan César Tovar being a prime example — who always gave it their all.

José Padilla recalled that Taylor always said that despite all the great players he played with and against, veteran Tigers star Al Kaline was the player he admired the most.47

Although the Tigers released Taylor in December 1973, he was by no means through. As Milton Richman of United Press International wrote in a 1975 feature, “St. Louis and Texas both wanted him for utility duty and Gene Mauch sought him as one of his coaches at Montreal.” Richman then described how Phillies general manager Paul Owens brought Taylor in for a meeting and said, “I’m not hiring you because you’re popular, and I’m not hiring you as a babysitter for (Willie) Montanez. I’d like to hire you because I think you can help us.”48

From 1974 through 1976, Taylor played largely the same role that Manny Mota did then for the Los Angeles Dodgers: pinch-hitter deluxe (though Tony took the field more often). He was especially successful coming off the bench in 1974, hitting .370 (17-for-46) with 2 homers and 12 RBIs as a pinch-hitter, which fueled his overall average of .328 in 73 plate appearances. He was also valuable in the clubhouse; young players and vets alike respected him and his feeling for both the game and people.49

That July the Associated Press wrote, “All Tony Taylor has to do is stick his head out of the Phillies’ dugout and the fans go wild.” This feeling too was mutual. “I love those people,” said Taylor of the Veterans Stadium fans. “If a guy gives one hundred percent they cheer for you. They know baseball, and they know whether a player is playing hard or not.” Larry Bowa added, “His knowledge of the game is unbelievable. Tony will watch a pitcher for an inning, then call me over and explain exactly what the guy is doing, diagnose his move toward first to help me stealing.”50

In 1975, Phillies manager Danny Ozark said, “Tony Taylor prepares himself like a surgeon. … He thinks along the same lines I do and he is halfway there before I ask him.” Tony himself said, “I believe the older you get, the harder you have to work. … It was hard to me to get used to not playing every day. But I’ve got to think, concentrate, know my job is to pinch-hit.”51

Taylor hit .243 in 124 plate appearances in 1975, as his pinch-hitting average fell off to .222 in 64 trips. Late in his career, he said, “When the legs go, the rest is quick to follow.”52 Yet he still had enough zip to beat out a bunt for his 2,000th big-league hit; the next day, in his final game of ’75, he stole his 234th and last base. He came back for his 19th season in 1976, saying, “If God be willing, I’d play another 19.”53 Paul Owens had compared Tony to George Blanda, the quarterback and placekicker for the Oakland Raiders who had only just retired at age 48 after the 1975 season.54

During that final season, Taylor was on the disabled list for most of four months. He got into only three games from Opening Day through July 30, all as a pinch-hitter. But after August he made 21 more pinch-hit appearances and even had three outings in the field. Despite his limited duty for the NL East champions, Tony had a vociferous backer who insisted that the veteran be included on the Philadelphia playoff roster. That was Dick Allen, who roomed with Taylor as a rookie in ’64. As author William Kashatus put it, Allen “gave the Phillies an ultimatum: unless Taylor was made eligible … he would refuse to play in the postseason.” Danny Ozark forged an uneasy compromise, making Taylor a coach. In 1999 Tony told Kashatus, “I was happy they included me as a coach, but it’s not the same as being a player.”55

The Phillies released Taylor in November 1976, and he retired as a player. Back in 1974, Larry Bowa had said, “He’d make a great manager, if someone is looking for a black manager. He knows more baseball than anybody I know. And he can communicate.”56 Instead, from 1977 through 1979, Tony remained with the big club as first-base coach. He was also a coach with Águilas del Zulia in the Venezuelan Winter League, where the Phillies had sent various players for seasoning. In the winter of 1978-79, in his first assignment as manager, Taylor led Zulia to the playoff finals. He was going to return the following season but had to come back to the US instead.57

It was too bad that Tony couldn’t be on the field in 1980 as the Phillies celebrated their first World Series victory. Yet he did collect a championship ring — his first of three, followed by two with the Marlins (1997 and 2003).58 During 1980 and 1981, he was a roving infield instructor in the Philadelphia chain.

Taylor spent 1982-83 and 1985-87 managing Phillies farm clubs ranging from short-season Class A ball up to Triple-A. In 1984 he served once again as a roving minor-league instructor (around that time he was also divorced from Nilda). Tony returned to the big club in 1988 as first-base coach and infield instructor. He stayed there through 1989. Of interest was an article that spring in Miami’s Spanish-language newspaper, El Nuevo Herald. Taylor said, “Yes, I won’t deny it, I believe that I am qualified to manage a [big-league] club, but it’s better that they leave me here [as a coach].”59

In 1990 Taylor joined the San Francisco Giants organization. He was with the Giants for three years, coaching two seasons at Double-A and a third at Triple-A. He then found an opportunity with the Florida Marlins — the new expansion club suited him because (like so many Cubans) he had come to live in the Miami area. Tony was a minor-league instructor for the Marlins through 1998 and then came back to the big leagues. From 1999 through 2001, he was an infield/bullpen coach, also working in the first-base box. He formed close relationships with the club’s Latino players.60

The Marlins then came under new management, and so for a couple of years Taylor was out of Organized Baseball, though he remained involved at the youth level in South Florida. He reconnected with the Marlins during their run to the World Series championship in 2003. Even though Taylor wasn’t with the team in an official capacity, pitcher Brad Penny reached into his own pocket to buy his friend a World Series ring — another event that moved the emotional Cuban deeply.61 He returned for a final season as bullpen coach in 2004.62 At last he then retired from pro baseball; he continued to reside in the Miami area. The Tony Taylor Baseball Academy, founded by brother Jorge in 1972, bore his name.

Taylor received a number of honors over the years. To name just two, the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame (in exile in Miami) inducted him in 1981, and the Phillies added him to their Wall of Fame in 2002. But perhaps more meaningful was what Milton Richman said in 1975: “Tony Taylor has a special way with people. It doesn’t matter who they are, other ballplayers, fans or the press. He’s to the Phillies what Ernie Banks was to the Cubs.”63

On August 3, 2019, Taylor suffered a series of strokes after returning to his Philadelphia hotel from a Phillies alumni event at Citizens Bank Park.64 The ballclub paid for a medically-equipped jet to fly him back home later that month, and he was reportedly making progress at a Miami rehab facility.65 However, complications from the strokes eventually led Taylor to be admitted to Hialeah Hospital, where he died on July 16, 2020.66 He was survived by his second wife, Clara, and children.

José Padilla remembered, “He was a very private person who never had a bad comment for any player, respected others, and was universally respected by all who knew him.” Clara Taylor shared with Padilla that her husband did not want a public wake, only a simple Mass with members of his family present.67 Padilla echoed the remarks of Jorge Taylor, who added that Tony was like a father to him.68

Tony Taylor described his personal connection and heart-on-the-sleeve approach to playing when he was named to the Wall of Fame. “The fans saw how much I loved the game,” he said. “Baseball is a fun game and I had a lot of joy in my heart when I played. They also saw the way I played. I gave my best every day.”69

Acknowledgments

This biography was originally published in 2012 and published in The Year of the Blue Snow: The 1964 Philadelphia Phillies (SABR, 2013). It was later included in Cuban Baseball Legends (SABR, 2016), which also came out in a Spanish-language edition. It was updated in August 2020; special thanks to Jorge Taylor, José Padilla, and Luis Tiant.

Sources

Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003).

Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003).

Ángel Torres, La Leyenda del Béisbol Cubano, 1878-1997 (Miami: Review Printers, 1996).

José A. Crescioni Benítez, El Béisbol Profesional Boricua (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc., 1997).

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.paperofrecord.com (The Sporting News online)

Notes

1 John Smith, “Cheering Is Taylor Made,” St. Petersburg Independent, March 29, 1976, 1-C.

2 His lifetime marks: .261 with 75 homers, a .321 on-base percentage, and a .352 slugging percentage.

3 “Tony Taylor is back where fans love him,” Associated Press, July 31, 1974.

4 “Biggest moment in whole life,” Associated Press, March 5, 1970. Confirmation that this is the right Jorge Taylor comes from the Lakeland (Florida) Ledger, June 7, 1960.

5 Early in the 20th century, some 115,000 Jamaicans emigrated to Cuba, mainly to work as laborers in the sugar industry. Margarita Cervantes-Rodríguez, International Migration in Cuba (University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010), 117, 121. Barbados and the Leeward Islands supplied the remaining one-third of immigrants to Cuba from the British West Indies. See also Marc McLeod, “Undesirable Aliens: Race, Ethnicity, and Nationalism in the Comparison of Haitian and British West Indian Immigrant Workers in Cuba, 1912-1939, Journal of Social History, Volume 31, No. 3, 1998.

6 Jorge Taylor, telephone interview with José Ramirez, July 22, 2020 (hereafter Jorge Taylor-Ramirez interview #1).

7 Jorge Taylor-Ramirez interview #1. Jorge Taylor, follow-up telephone interview with José Ramirez, August 9, 2020 (hereafter Jorge Taylor-Ramirez interview #2).)

8 E-mail from Andrés Pascual to Rory Costello, August 5, 2012. Contrary to Jorge Taylor, Pascual thought the Taylors did not have any Chinese heritage.

9 In 1928, William Tin Lai (“Buck”) was on the New York Giants roster early in the season but did not get into a game. Bobby Balcena, whose parents were both Filipino, played briefly in the majors in 1956. However, it’s open to debate whether Filipinos are Asians or Pacific Islanders.

10 José Padilla, telephone interview with José Ramirez, July 19, 2020 (hereafter Padilla-Ramirez interview)..

11 Hugh Thomas, Cuba, or The Pursuit of Freedom, New York: Harper & Row, 1971), 275.

12 Joe Halberstein, “The Tony Taylor Affair,” Bucks County (Pennsylvania) Courier Times, August 3, 1975.

13 “10 More Dollars and Tony Taylor Would Have Quit,” Reading Eagle, May 10, 1970, 65.

14 Ángel Torres, La Leyenda del Béisbol Cubano, 1878-1997 (Miami: Review Printers, 1997).

15 Andrés Pascual, “El mejor intermedista cubano ha sido Tony Taylor,” El Tubeyero 22 blog, June 8, 2011 (http://eltubeyero22.mlblogs.com/2011/06/08/el-mejor-intermedista-cubano-ha-sido-tony-taylor/)

16 Sam Lacy, “Sam Lacy’s A to Z,” The Afro American, July 23, 1960, 13.

17 “10 More Dollars and Tony Taylor Would Have Quit.”

18 “10 More Dollars and Tony Taylor Would Have Quit.”

19 Scott Lauber, “Pilgrimage into history,” The News-Journal (Wilmington, Delaware), March 5, 2006, C1.

20 Bill Rives, “Dazzling Defense Helped Dallas to Dominate Race,” The Sporting News, September 11, 1957, 39.

21 Hal Lebovitz, “‘Minnie to Put New Hustle in Tribe’– Lane,” The Sporting News, December 11, 1957, 4.

22 Edgar Munzel, “Bruins Tab Taylor as One-Man Answer to Pair of Problems,” The Sporting News, March 26, 1958, 7. The Sporting News, April 9, 1958, 2.

23 Edgar Munzel, “Vet Thomson, Kids Taylor, Goryl Help to Give Bruins Fresh Look,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1958, 27.

24 “10 More Dollars and Tony Taylor Would Have Quit.”

25 Munzel, “Vet Thomson, Kids Taylor, Goryl Help to Give Bruins Fresh Look.”

26 Lacy, “Sam Lacy’s A to Z.”

27 Edgar Munzel, “Hats Off! Tony Taylor,” The Sporting News, May 11, 1960, 21.

28 Allen Lewis, “Phils Flash Speed Warnings on Heels of 4-Man Cub Swap,” The Sporting News, May 25, 1960, 17.

29 “10 More Dollars and Tony Taylor Would Have Quit.”

30 Sporting News Official Baseball Register, 1965.

31 Halberstein, “The Tony Taylor Affair.”

32 José Ramírez, “Pancho Herrera,” SABR BioProject (http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/6da969d5)

33 Luis Tiant, telephone interview with José Ramirez, July 19, 2020.

34 Halberstein, “The Tony Taylor Affair.”

35 Stan Hochman, “Phillies Claim Their Taylor Sews Up Second,” Baseball Digest, February 1964, 80.

36 Allen Lewis, “Mauch Pegging Tony Taylor as ‘Comeback Kid,’ ” The Sporting News, February 28, 1962, 19.

37 Tony Solar, “Cuba Big Leaguers Play Benefit Here,” Miami News, October 5, 1962, 3C.

38 Hochman, “Phillies Claim Their Taylor Sews Up Second.”

39 Randy Miller, “Taylor reflects on Phils’ collapse of 1964,” Bucks County Courier Times, September 23, 2004.

40 Allen Lewis, “Phils Heave a Sigh of Relief for Nixing All Bids for Taylor,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1967, 16.

41 “Cuban Players Hail Eckert for Latin-Ball Rule,” The Sporting News, October 8, 1966, 52.

42 Rich Westcott, “Phils Alerted to Taylor Rebound; Swat Champ in Puerto Rico Loop,” The Sporting News, March 2, 1968, 33.

43 “Perennial Extra Man Tony Taylor Called Most Underrated Player By New Manager,” Associated Press, March 21, 1970.

44 “Biggest moment in whole life.”

45 “Phils Trade Tony Taylor to Detroit,” Associated Press, June 13, 1971.

46 Tom Cornelison, “Pirates’ Kurt Bevacqua: A Man on the Move,” Sarasota Journal, March 25, 1974, 2D.

47 Padilla-Ramirez interview.

48 Milton Richman, “Phillies Will Honor Taylor Again,” United Press International, August 1, 1975.

49 Richman, “Phillies Will Honor Taylor Again.”

50 “Tony Taylor is back where fans love him.”

51 “Tony Taylor Bigger Hero Than Ben Franklin To Phillies’ Fans,” United Press International, May 11, 1975.

52 Smith, “Cheering Is Taylor Made.”

53 Smith, “Cheering Is Taylor Made.”

54 Richman, “Phillies Will Honor Taylor Again.”

55 William C. Kashatus, Almost a Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the 1980 Phillies (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 119-120.

56 “Tony Taylor is back where fans love him.”

57 Luis Verde, Historia del Béisbol en el Zulia (Maracaibo, Venezuela: Editorial Maracaibo, S.R.L., 1999).

58 Miller, “Taylor reflects on Phils’ collapse of 1964.”

59 “Tony Taylor: ¿Manager? No, ‘Mejor Coach,’” El Nuevo Herald (Miami, Florida), March 20, 1989, 4B.

60 Ángel Torres, “Tony Taylor premiado por el Salón de la Fama del Deporte Cubano,” Diario Las Américas, March 16, 2010 (http://www.diariolasamericas.com/noticia/95840/tony-taylor-premiado-por-el-salon-de-la-fama-del-deporte-cubano). Joe Frisaro, “Marlins name Taylor bullpen coach,” MLB.com, January 7, 2004 (http://mlb.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20040107&content_id=626072&vkey=news_mlb&fext=.jsp&c_id=mlb).

61 “Chance to Play Catch-Up,” Miami Herald, April 24, 2004, 3D. “Oliver at Home in Coors,” Miami Herald, April 27, 2004, 5D.

62 Frisaro, “Marlins name Taylor bullpen coach.”

63 Richman, “Phillies Will Honor Taylor Again.”

64 Matt Breen, “Phillies great Tony Taylor suffers stroke after leaving Citizens Bank Park celebration,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 4, 2019.

65 Matt Breen, “Phillies great Tony Taylor recovering in Miami after suffering a stroke in Philadelphia,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 19, 2019.

66 Jorge Taylor-Ramirez interview #2.

67 Padilla-Ramirez interview.

68 Jorge Taylor-Ramirez interview #1.

69 Don Bostrom, “Tony Taylor returns home,” The Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania), July 21, 2002.

Full Name

Antonio Nemesio Taylor Sánchez

Born

December 19, 1935 at Central Alava, (Cuba)

Died

July 16, 2020 at Hialeah, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.