Philadelphia Phillies team ownership history

This article was written by Rich Westcott

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

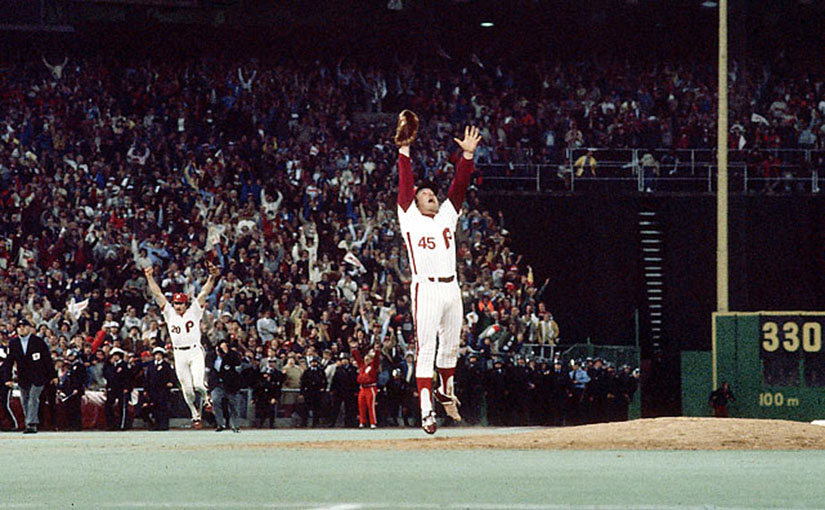

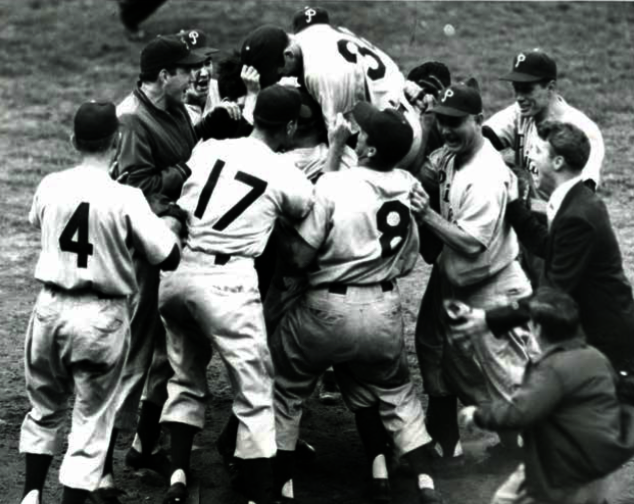

Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Tug McGraw celebrates after closing out Game Six of the 1980 World Series, clinching the first championship in franchise history. (Courtesy of the Philadelphia Phillies)

In the Beginning

The first National League game in Philadelphia was played in 1876 with the Boston Red Stockings facing the Philadelphia Athletics, one of several of the city’s early teams with that name. Playing at Jefferson Park before an estimated crowd of about 2,000, the Athletics lost that game, 6-5. By the end of the season, the Athletics had also lost their place in the league.

With insufficient funds, an unwillingness to waste any more time playing in a futile season in which they had posted a 14-45 record, and a conflicting schedule of exhibition games, the Athletics refused to make their last Western road trip. Accordingly, a few months later, the team was expelled from the league.

Although the Athletics would continue to play as an independent team and, in 1882, another team called the Athletics was awarded a franchise in the new American Association, Philadelphia was left without a National League team for the next six years. That all changed in 1883.

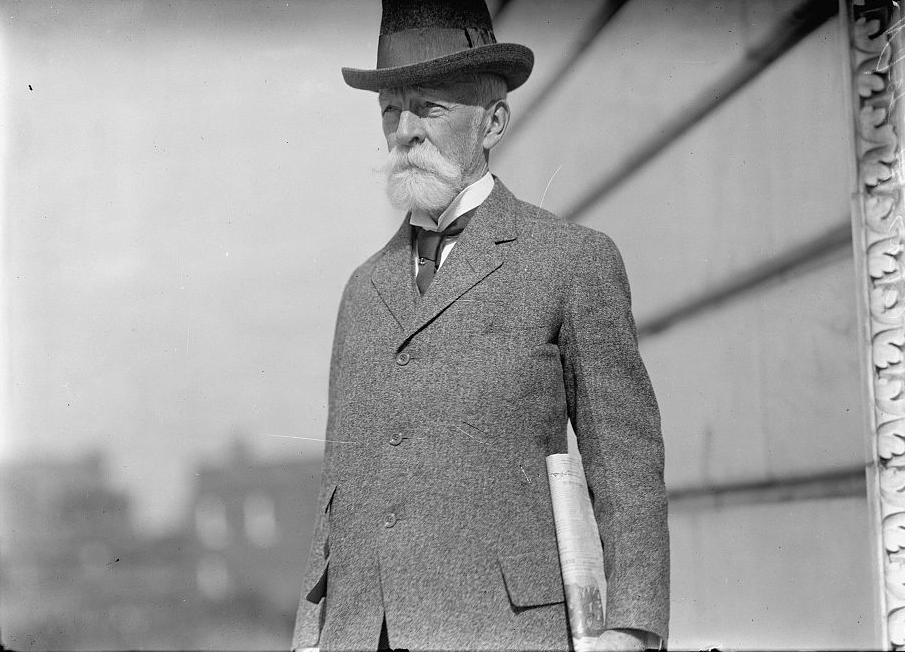

William Hulbert had been the president of the National League, but early in the 1882 season, he died of a heart attack. His place was filled by Abraham G. Mills, a former Army officer, a highly successful New York attorney, and a former player and strong supporter of the game of baseball.

At the time, the eight-team National League included clubs from Troy, New York, and Worcester, Massachusetts. But soon after he became president, Mills launched a movement to rid the league of those two squads, replacing them with teams from New York City and Philadelphia.

“We’ve got to get those big cities back into our league,” he said. “Both New York and Philadelphia have tremendous futures, and some day their populations will be in the millions. If we permit the American Association to entrench itself in these cities, the Association — not we — soon will be the real big league.” Mills ordered the dissolution of the Troy franchise and moved it down the Hudson River to New York. Then he shifted his focus to the Worcester Ruby Legs (or Brown Stockings as some called them). “They’re not big enough to support National League ball,” he said. “I’d like to see that club in Philadelphia.”1

Late in 1882, Mills contacted his old friend Alfred J. Reach, a former player and now the owner of a highly profitable sporting-goods business in Philadelphia. Would Reach be interested in taking over a new team in Philadelphia? Reach jumped at the chance. Soon the Worcester franchise was also dissolved and a new team was set up in Philadelphia. The City of Brotherly Love finally was back with a team in the National League.

Al Reach Reaches Out

Al Reach was the classic American success story, an immigrant who rose from the streets of New York to become a millionaire. Whether it was blazing a trail as a pioneer baseball player and owner, or building a mammoth sporting-goods company, practically everything Reach did was done well and with good results. As a player, he was one of the first to receive a salary. As a businessman, he was one of the first to manufacture baseball bats, balls, and gloves.

Al Reach was the classic American success story, an immigrant who rose from the streets of New York to become a millionaire. Whether it was blazing a trail as a pioneer baseball player and owner, or building a mammoth sporting-goods company, practically everything Reach did was done well and with good results. As a player, he was one of the first to receive a salary. As a businessman, he was one of the first to manufacture baseball bats, balls, and gloves.

Born in 1840 in London, England, where his father was a prominent cricket player, Reach was brought to the United States at the age of one. He was raised in Brooklyn, where his industrious nature surfaced early. He sold newspapers on Broadway, then at the age of 15 he took a job in an iron foundry. Toiling as an iron molder with heavy tools and near the hot furnaces, he worked 12-hour days. Some of his work went into the construction of New York’s finest hotels of the day along Fifth Avenue.

When he wasn’t working, Reach played baseball, first on vacant lots and then with some of the local teams in the Brooklyn area. Although left-handed, he was originally a catcher.

In his early 20s, Reach played for the Brooklyn Eckfords, a prominent club in the New York area.

During a series in Philadelphia, Al attracted the attention of Colonel Thomas Fitzgerald, manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, an independent team that traveled the country. Fitzgerald persuaded Reach to join the Athletics by offering the young player a contract and a full-time salary. Reach accepted the offer and, although he continued to live in Brooklyn, joined the Athletics in 1863.

In those days, some teams paid a few of their players under the table, but Reach is usually credited with being the first man to accept pay openly. And he soon justified his salary, which was said to be $1,000 for the season. Installed as a left-handed second baseman, young Al quickly became the team’s leading hitter.

In 1868 he was named first-team All-American by the New York Clipper. The 5-foot-6, 155-pound Reach was usually good for three or four hits a game, and he earned a reputation as the home-run king of the era. Moreover, he developed a big local following.

In 1871 a new fully professional league, the National Association, was formed. A team called the Athletics not only joined, it captured the pennant, winning 22 of 29 games. Reach, by then a resident of the Frankford section of Philadelphia, led the team in hitting with a .348 average. Later, he became the team’s manager for the 1874 and 1875 seasons.

By this time, Al’s entrepreneurial instincts had been activated. He opened a cigar store and ran it before and after games. The store became a local hangout for sporting types. Reach also noticed the increasing demand for baseballs, bats, and other sporting goods, and the corresponding absence of any stores that supplied such items. The observation prompted him to open a sporting-goods store in 1874, one year before his playing days ended.

The store thrived and by 1881 Reach moved to a larger store. Simultaneously, he took in a partner, Benjamin J. Shibe, an expert on leather and a manufacturer of horse whips. The partnership was formed to launch a business that would manufacture sporting goods. Soon the men opened a plant in North Philadelphia. Later, Shibe would become the original owner of the new American League’s Philadelphia Athletics.

Although he had become a full-time businessman, Reach retained his contacts in baseball. After he was approached by Mills about starting a team in Philadelphia, Reach enlisted the aid of Colonel John I. Rogers, a prominent lawyer, a former city comptroller, a colonel in the Philadelphia National Guard, and a member of the Pennsylvania governor’s staff. Rogers, a native Philadelphian and a University of Pennsylvania graduate, was in later years one of the creators of baseball’s reserve clause. Ultimately, he and Reach became the principal owners of the new team, each holding 43 percent of the club’s stock with a few friends of theirs holding the remaining shares.

There were no players involved in the transaction. They had been gobbled up by other teams as soon as it became apparent that the failing Worcester team would be folded. Thus Reach and Rogers had to start from scratch, recruiting players and even finding a ballpark.

The players came from an assortment of directions, some locally and some from minor professional teams elsewhere. An old ballfield built in 1860 on the block surrounded by 24th and 25th Streets and Ridge and Columbia Avenues called Recreation Park was totally refurbished by Reach. Because its nickname would suggest its geographic location, the team was named the Philadelphia Phillies. It would go on to become the longest continuous, one-city, one-nickname franchise in baseball history. (Neither Quakers, Live Wires, Blue Jays, Whiz Kids, nor any other name was ever officially registered as the team’s nickname.)

The first team, in 1883, was a dismal failure. After losing its first game, 4-3, to the Providence Grays, the Phillies posted a record of 17-81. The main pitcher, John Coleman, set an all-time record with 48 losses. (He had 12 wins.) Reach fired the team’s first manager, Bob Ferguson, after the Phillies lost 13 of their first 17 games, replacing him with outfielder Bill “Blondie” Purcell. But Reach was not discouraged even though some of his friends tried to convince him that owning a professional baseball team was a bad idea. The Phillies, they argued, should be disbanded, and Reach should concentrate on less futile ways of spending his money.

Reach refused to wither under such pressure. The following season he brought in new players, and most importantly, turned the managerial reins over to Harry Wright, a baseball pioneer himself, and one of the game’s premier managers. In 1869 Wright was the player-manager with the first all-professional team, the Cincinnati Redlegs. Two years later, he became the manager of the Boston Red Stockings, with whom he won six pennants in 11 seasons and was the skipper in the first National League game in Philadelphia.

Wright was given a small number of shares in the team from Reach’s friends’ holdings. Immediately, the Phillies improved tremendously. In 1884 the club moved up to sixth place, and the following year it jumped up to third with the club’s first season over .500 (56-54-1). That started an 11-year streak in which the team would finish in the first division each season, winning as many as 87 games in 1892.

In 1887, with the master plan devised by Reach, the team also moved into a new showplace stadium originally called Philadelphia Base Ball Park. Located on the corner of Broad Street and Lehigh Avenue in North Philadelphia, it was built at a cost of $101,000 alongside a creek and over a dump that required 120,000 wagonloads of dirt to fill the pits and gullies and bring it to street level. It was regarded as the finest ballpark in the nation, a magnificent showplace that was envied by all other cities. The most modern and advanced ballpark of the era, it was the first one that was built mainly with bricks instead of wood and was the first ballpark to include pavilions for seating. Its original capacity was 12,500. Later called Huntingdon Street Grounds and then Baker Bowl, the park was used by the Phillies for 51½ years. Along the way it was the site of several disasters, and by the end of its use as a major-league baseball field in 1938, had become a decrepit and obsolete park that was the laughingstock of baseball.

Starting in the late 1890s, the club became the residence of a number of future Hall of Fame players, including Ed Delahanty, Nap Lajoie, and Elmer Flick, who launched their careers with the Phillies, plus Sam Thompson, Billy Hamilton, Tim Keefe, Roger Connor, and Dan Brouthers, all of whom came from other teams. From 1891 through 1895, Delahanty, Hamilton, and Thompson became the first all-Hall of Fame outfield, playing together and in one season (1894) all hitting over what was then calculated as .400.

It was Reach who gambled on spending $1,900, a staggering figure in those days, for Delahanty, a raw young hitter playing in the minors at Wheeling, West Virginia, and one of five brothers who would play in the big leagues. Ultimately, Delahanty became arguably the best hitter in Phillies history, compiling a batting average over .400 three times and leading the league in numerous hitting categories during his 13 seasons in Philadelphia. When he died in 1903 in a mysterious accident that ended with his washing over Niagara Falls, he had compiled a lifetime batting average of .346, which ranks as the fourth highest in major-league history.

Under Reach, the Phillies finished second twice, third six times, fourth six times, sixth twice, seventh once, eighth twice, and tenth once. Although the club never won a pennant, Reach developed it into one of the cornerstones of the National League. In his 20 years with the team, he built two ballparks, the Phillies finished in the first division 14 times, and the club posted a winning record of 1,339-1,260 for the best percentage (.515) under any club president until Ruly Carpenter. Reach also managed the team for 11 games in 1890 when three substitute pilots had to fill in for Wright after he developed a case of temporary blindness.

There were, of course, disappointments and problems during Reach’s administration. The club engaged in bitter battles over players — in 1890 with the Brotherhood (or Players’) League, and in 1901 with the American League. The losses of players to those leagues, especially Delahanty, Lajoie, and Flick, the sudden death of star pitcher Charlie Ferguson after just four brilliant seasons in the league during which he won 99 games, a devastating fire in 1894 that destroyed the ballpark and forced the Phillies to play part of the season on the University of Pennsylvania’s field, and the players’ mutiny over the abusive tactics of manager George Stallings in 1897-98, all contributed to a less-than-smooth tenure for Reach.

By the mid-1890s, Reach was spending more time with his sporting-goods business and less time with the Phillies. The militant, arrogant, and often stubborn Rogers, who frequently battled with Reach, took over control of the operation of the team. Meanwhile, Wright, later named “The Father of Professional Baseball” for his many contributions to the game, left the team after the 1893 season when he was not offered a new contract by Rogers..

A few years later, another colorful figure earned a place in Phillies history when he was appointed the team’s manager. Bill Shettsline had originally been employed by the team as a handyman. He then rose to ticket taker and then office manager. During the 1898 season, he was named the team’s manager, replacing the fired Stallings. Afterward, Shettsline, a rotund Philadelphia native, went on to manage the team for four full seasons, in 1899 guiding it to 94 wins, a figure than went unsurpassed until 1976. Under Shettsline, the Phillies finished third twice and second once before crashing to seventh in his last year, 1902, when they drew just 112,066 fans for the entire season. He was dismissed after that season, and named the club’s business manager. Three years later, he became the Phillies’ president.

By then, the A. J. Reach Company was flourishing. The company opened another plant in Brantford, Ontario, and moved its store to a large building in downtown Philadelphia. The relationship between Reach and Shibe couldn’t have been better. Reach’s son George married Shibe’s daughter. And when the American League began, Reach, who in 1899 had unsuccessfully offered to sell his shares in the Phillies to Rogers, recommended his partner for a franchise in Philadelphia.

The ensuing sequence was laced with irony. Shibe became the first owner of the American League’s Philadelphia Athletics. And the Reach ball became the official ball of the new league. Yet, the presence of the young circuit and its player raids on the Phillies were a main factor in Reach’s decision to end his ownership in the National League.

In 1901, financially crippled by the raids, Reach and Rogers had to secure a loan from Pittsburgh Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss during the grueling legal battle with the American League. The Americans had signed Phillies’ star Nap Lajoie, who had won the AL’s first batting crown with what would be the highest average (.426) in AL history. The Phillies’ owners sought an injunction to stop Lajoie from playing with any other teams. When the Phillies won the case, American League President Ban Johnson moved Lajoie to the Cleveland Blues, a move the Phillies did not contest and where he spent most of the rest of his Hall of Fame career.

One year later, as their relationship became increasingly acrimonious, Reach and Rogers sold the Phillies to a syndicate headed by James Potter for $180,000. Reach and Rogers retained the title to Philadelphia Park, leasing it back to the new owners for $10,000 per year. Seven years later, Rogers died of a heart attack.

Eventually, Reach also sold his sporting-goods store. But his manufacturing company continued to crank out new baseballs, using a special winding machine that Reach invented. The company also produced a huge assortment of other sporting goods, and for a number of decades it published the official American League Reach Baseball Guide.

The Philadelphia Ledger in 1915 described Reach’s operation in glowing terms. “The establishment of Mr. Reach has grown to larger proportions, and the name is synonymous with baseball,” it said. The Reach Company and the A.G. Spalding Company, founded by another old baseball-playing pioneer, were the dominant firms in the sporting-goods field in the country.

Before retiring, Reach sold his company to the rival Spalding firm. He lived his final years in Atlantic City. Reach died on January 14, 1928. He left an estate valued at $1,017,868.

The Phillies first owner is buried in West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, just outside of Philadelphia. Also buried there are Harry Wright and Benjamin Shibe.

On the Road to Mediocrity

After performing for 20 years under the same ownership and rising to a place among the stronger franchises in the league, the Phillies vaulted onto a path of chaos.

During a 10-year period following the sale of the team to the Potter group, the Phillies would have four owners. They would be commanded by six presidents, one of whom would get barred from baseball for life. The team would have four managers, once lost 103 games, and drew just 140,771 paying customers one season. Meanwhile, the rival Athletics of the new American League won five pennants and three World Series between 1902 and 1913 while becoming the favorite team of Philadelphia baseball fans.

The Potter group’s purchase of the team launched the Phillies’ downfall. Potter, a socialite and a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, was also a stockbroker whose clients had mostly not achieved the social status to which he was accustomed. But he induced many of them to join him in his investment in the sport of “base ball.” In addition, Dreyfuss, who had earlier loaned Reach and Rogers money to fight the new American League and had been paid off secretly with Phillies stock, took the position of running the team behind the scenes. It was a clear conflict of interest, despite the fact that such things were fairly common during that era, as the Taft organization, among others, would demonstrate.

After he bought the team and became president, it didn’t take long for Potter’s collapse to begin. During a game on August 6, 1903, the fans were attracted to a disturbance behind the left-field bleachers in which two drunks were taunting a group of young girls. When one girl fell and she and her friends started screaming “help” and “murder,” fans ran to the top of an overhanging balcony protruding about 30 feet above the stands to see what the commotion was about. The balcony fell under the weight, crushing fans and sending them into the cement pavement below. Twelve fans were killed and 232 were hospitalized. More than 80 lawsuits against Reach and Rogers, still the owners of the ballpark, followed, and although they, as was Potter, were eventually absolved of blame, the two eventually sold the ballpark to the incoming Taft family

The Phillies finished seventh that year. In 1904 they dropped to eighth. After the season, Potter realized that baseball wasn’t his game. In 1905, he got out. The stockholders held a reorganization meeting and the presidency of the team was passed to Bill Shettsline.

Shettsline, a resident of Glenolden in Delaware County, served through the 1908 season, during which time the Phillies finished third once and fourth three times. In his most important move, coming shortly after he was named president, Shettsline signed a semipro outfielder. His name was Sherry Magee, and he would go on to win a batting title in 1910 while becoming one of the top Phillies players of his era. Under Shettsline’s leadership, the 1908 Phillies drew 420,660, a club record to that point.

After Potter pulled out, the remaining Phillies stockholders sold the team to Charles Phelps Taft, a native of Cincinnati and a graduate of Yale University and Columbia University Law School, and Charles Murphy, who was part-owner of the Chicago Cubs, thanks to money Taft had loaned him to purchase controlling interest in the team. The son of a United States attorney general who later served as US secretary of war, Taft was the younger brother of William Howard Taft, the nation’s 27th president.

After Potter pulled out, the remaining Phillies stockholders sold the team to Charles Phelps Taft, a native of Cincinnati and a graduate of Yale University and Columbia University Law School, and Charles Murphy, who was part-owner of the Chicago Cubs, thanks to money Taft had loaned him to purchase controlling interest in the team. The son of a United States attorney general who later served as US secretary of war, Taft was the younger brother of William Howard Taft, the nation’s 27th president.

During his career, Taft served as a successful attorney, a member of the Ohio State Legislature, and a member of the US Congress. He also spent 10 years as editor of the Cincinnati Times-Star and later owned the Cincinnati Post. His work with newspapers ultimately became the focus of his career.

Taft was the major stockholder in the team until 1913. During that period, the Phillies finished in fourth place five times, in fifth twice, and second and third each once. Along the way, he put Murphy in charge of the team after purchasing his stock in the Cubs

Murphy was a former newspaper reporter who had become one of baseball’s first publicity chiefs, first with the New York Giants and then with the Cubs. Then, after buying 53 percent of the stock in the Cubs, he became the team’s president in 1906. He stayed until 1914 when he was ousted by the league’s other owners after an acrimonious relationship that came to an end after Murphy was accused of mishandling the contracts of some of his players, especially former player and current manager Johnny Evers.

In 1909, however, Taft had sold his controlling interest in the team to Israel Durham and James McNichol, Philadelphia’s two top Republican political bosses. Along with banker Clarence Wolf, they formed a syndicate and bought the club with Durham replacing Shettsline as president. Shettsline returned to his position as the team’s business manager.

Durham, who had served as a Philadelphia police magistrate, a state senator, and the state insurance commissioner, had high hopes for the team. “We will save neither money nor effort to bring a first National League championship to Philadelphia,” he announced.2

But even as he took over the presidency, Durham was a sick man. And he died during the 1909 season. After his death, neither McNichol nor Wolf decided they had any real interest in running the team. They sold it on November 26, and the new buyer was a surprise to everyone. His name was Horace Fogel and he was a well-known local sportswriter.

Fogel took over the team’s presidency in 1909. He insisted that he was running the whole show while claiming that he was the sole owner. In fact, Taft had loaned him a large sum of money to purchase shares in the ballclub that was now said to be worth $350,000, and was still the team’s largest stockholder.

The highlight of Fogel’s tenure came in 1911 when the Phillies bought a young pitcher named Grover Cleveland Alexander from a minor-league team in Syracuse for $750. Alexander won a league-leading 28 games as a rookie in 1911, launching a Hall of Fame career in which his 373 victories made him the fourth-winningest pitcher in major-league history. Also during Fogel’s reign, the Phillies signed Gavvy Cravath, a 31-year-old journeyman who would win six home-run crowns in the next seven years while holding the career record for home runs (119) until it was broken by Babe Ruth.

Things were never dull when Fogel was president. He tried unsuccessfully to change the team’s nickname from Phillies to Live Wires. His sportswriting buddies ignored the idea. He tried to have a wedding staged inside a lion’s cage at the pitcher’s mound with the lion acting as one of the witnesses. He fired manager Bill Murray and replaced him with catcher Red Dooin, who made the club better and more exciting. In 1911 Fogel swung what was the biggest trade the Phillies had made up to that point with pitchers George McQuillan and Lew Moren, third baseman Ed Grant, and outfielder John Bates going to the Reds for third baseman Hans Lobert, center fielder Dode Paskert, and pitchers Jack Rowan and Fred Beebe.

Things were never dull when Fogel was president. He tried unsuccessfully to change the team’s nickname from Phillies to Live Wires. His sportswriting buddies ignored the idea. He tried to have a wedding staged inside a lion’s cage at the pitcher’s mound with the lion acting as one of the witnesses. He fired manager Bill Murray and replaced him with catcher Red Dooin, who made the club better and more exciting. In 1911 Fogel swung what was the biggest trade the Phillies had made up to that point with pitchers George McQuillan and Lew Moren, third baseman Ed Grant, and outfielder John Bates going to the Reds for third baseman Hans Lobert, center fielder Dode Paskert, and pitchers Jack Rowan and Fred Beebe.

One night in 1912 Fogel was drinking with some writer friends, and at one point said the National League pennant race was fixed. Fogel said that the umpires were told to favor the New York Giants, and that St. Louis Cardinals manager Roger Bresnahan always played his weakest lineup against his former team. The writers in Fogel’s group wrote articles about his comments. Ultimately, National League owners held a meeting in New York, Fogel was found guilty of five of seven charges, and was banned forever from the National League. Albert Wiler was installed as the interim president of a franchise that was in a state of limbo.

Meanwhile, Taft sold his remaining interest in the Phillies and soon thereafter purchased the Chicago Cubs, a team he owned until he sold it after the 1915 season. Wiler served for only three months, leaving the position when a syndicate headed by William H. Locke purchased the team from Taft, who had become the team’s principal owner.

Locke, Dreyfuss’s top assistant with the Pirates, had a lifelong desire to own and operate a major-league baseball team. He put together a group in which he was the biggest investor and which included a cousin, William F. Baker, a former New York City police commissioner and a man of considerable means. Another shareholder was Lewis C. Ruch, a New York businessman. Baker became the second biggest investor in the syndicate. Locke made his bid, which was accepted, and on January 15, 1913, his dream became reality.

Locke worked hard to build a team that had finished third once, fourth five times, and fifth twice in the previous eight years. He held daily conferences with manager Dooin on ways to improve the team. He tried to buy up all outstanding stock so that his interests would be solely in command.

But his efforts suddenly ended. Seven months after he assumed control of the team, Locke died. His passing changed the course of the franchise’s history. His death led to the tenure of William F. Baker, who became the team’s primary owner and president. Two years later, Baker got what Locke had wanted so badly: The Phillies won the National League pennant. Baker would own the team and serve as its president from 1913 to 1930.

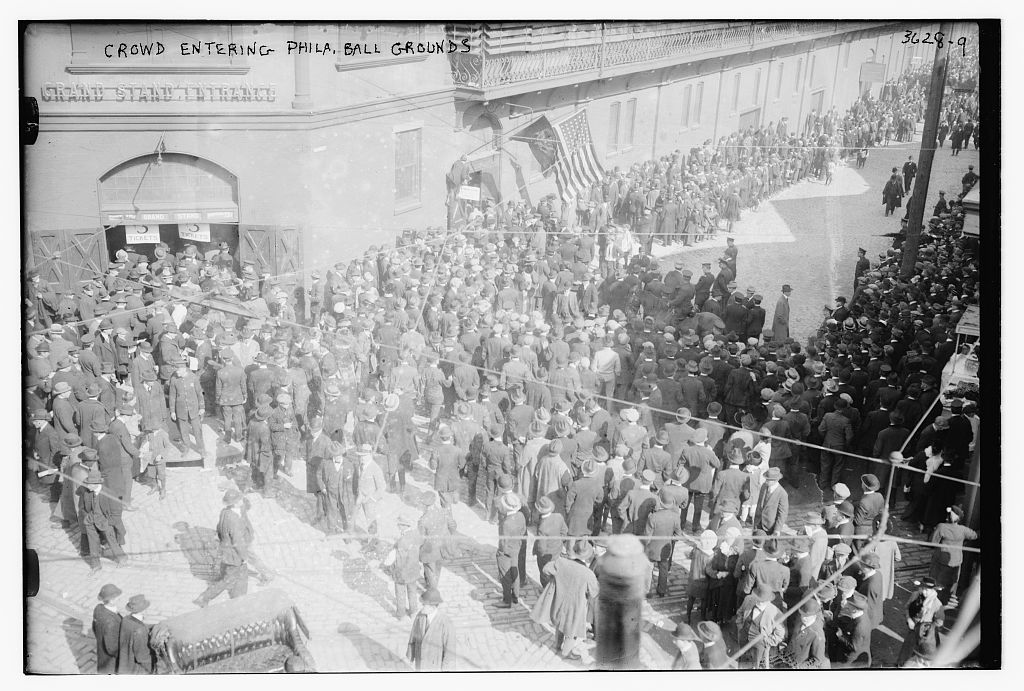

Philadelphia Phillies fans enter the Baker Bowl for a game in 1915. (Library of Congress, Bain Collection)

The Start of a Catastrophic Era

In his 18 years with the Phillies, Baker took the franchise from good days to bad days. He made some of the worst trades in major-league history, allowed his ballpark to deteriorate so badly that it became hazardous. He won one pennant, and finished last eight times.

Baker ran his operation on a financial shoestring, even when things were going well in the mid-teens. During the later years of his ownership, he was constantly trading whatever talent he had to get cash to meet the payroll.

Baker died in Montreal on December 4, 1930, a controversial figure in Philadelphia to the end. The big complaint about him was that he never dipped into his own pocket to finance the team. Although he was a wealthy man, he chose instead to let the team pay for itself. In addition, some Philadelphians resented the fact that he spent most of his years as team president commuting back and forth from New York City instead of establishing a residence in Philadelphia

Baker died in Montreal on December 4, 1930, a controversial figure in Philadelphia to the end. The big complaint about him was that he never dipped into his own pocket to finance the team. Although he was a wealthy man, he chose instead to let the team pay for itself. In addition, some Philadelphians resented the fact that he spent most of his years as team president commuting back and forth from New York City instead of establishing a residence in Philadelphia

Baker also failed to endear himself to the loyal Phillies fans in 1925 when, in Common Pleas Court testifying in a suit contesting the ownership of shares of Phillies stock, Baker admitted that he was hoping to sell the team eventually. “We (Baker and his partners) thought that when I could get the club up to the first division, we could get a good price for it,” he said.

In reality, Baker was never a baseball man before he took over the presidency of the Phillies. He assumed leadership only to protect his investment. But once he got his feet wet, Baker became a mover and shaker. Shortly after he took over the team, he named the Phillies ballpark after himself. The stadium would be called Baker Bowl for the rest of its long life. Baker fired eight different managers during his tenure, including Pat Moran, who had led the team to the 1915 pennant.

Baker showed a total lack of understanding for the game after the 1913 season when the Federal League was offering many baseball stars much larger contracts. Instead of fighting back, Baker offered small or no salary increases to those Phillies who were approached. As a result, he lost some of his top players.

But after the 1914 season, Baker did something right. He changed managers after the team finished a disappointing sixth, replacing Dooin with Moran. “I didn’t have to go far to find a successor,” Baker said. “I found him right on the ballclub in coach Moran. I’ve watched Pat and like the way he goes about his work. He knows a lot of baseball. I think he’ll make us a fine manager.”3 Baker was right. The first year under Moran, the Phillies won their first pennant.

It has been argued that the Phillies won the 1915 pennant despite Baker, not because of him. Their chances of winning the World Series that year were hindered badly by his desire to generate more revenue by roping off some areas in left and center field, allowing spectators to stand on the playing field between the ropes and the outfield wall.

After Alexander won the first game, and Woodrow Wilson in Game Two became the first president to attend a World Series, the Phillies lost four games in a row to the Red Sox. In the fifth and final game of the Series, Harry Hooper, who had hit two home runs all season, hit two into the roped-off area and Duffy Lewis hit one to give the Red Sox a 5-4 victory. Baker took a terrible beating in the national press, which called him the goat of the Series.

After the 1917 season, Baker made one of the worst trades in the history of the franchise. He moved Alexander and Bill Killefer to the Cubs for $60,000, pitcher Mike Pendergast, and catcher Pickles Dillhoefer. Baker insisted at the time of the deal that it was made strictly because Alexander was going to be drafted for service in the World War and there was no way he was going to gamble on Ol’ Pete’s safe return. But when pressed on the issue several years later, Baker told the real reason for the trade. “Because I needed the money,” he admitted.4

One of the biggest critics of the Alexander trade was manager Moran, who let it be known that he and the boss did not see eye to eye on it. Baker’s response was to fire Moran at the end of the 1918 season.

The Roaring Twenties were not accompanied by roaring crowds at Baker Bowl. Only once in the decade did attendance surpass 300,000. From 1919 through 1930, the Phillies finished in eighth place seven times and in seventh place twice.

Baker again incurred the wrath of Phillies fans by continuing to trade stars for lesser players and large sums of cash. Included in this discarded batch were stars like shortstop Dave Bancroft, pitcher Eppa Rixey, outfielder Irish Meusel, and catcher Jimmie Wilson. In one deal, Baker sent outfielder George Whitted to the Pittsburgh Pirates for outfielder Casey Stengel. He did make a superb trade in 1917, however, when he acquired Cy Williams from the Chicago Cubs. Williams went on to lead the National League in home runs four times, three of them during his 13 seasons with the Phillies, thereby etching his name as one of the great hitters in Phillies history.

Even Giants manager John McGraw, however, who had been the beneficiary of some of Baker’s trades, got tired of Baker’s foibles. He ripped Baker for his manner of conducting business. He said that he, along with other owners, would run Baker out of baseball.

The Phillies president fought back. He accused McGraw of tampering with players on other teams, making them dissatisfied with playing anywhere but for the Giants. McGraw never got Baker out of baseball, and Baker continued to sell whatever good players he had. He also put a 12-foot screen atop the already high 40-foot right-field wall, which was 282 feet down the line, to cut down on Chuck Klein’s home runs, an act done so the slugger could not ask for a higher salary.5

One month before he died, Baker made his last trade, sending Lefty O’Doul, who had hit .398 and .383 in his two seasons with the Phillies, and Fresco Thompson to Brooklyn. In exchange, he received three lesser players and $25,000 in cash.

At his funeral in New York, Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis praised Baker as “a pillar of the baseball community.” In reality, his policies were a bitter pill for Phillies fans to swallow. And because of the sad state of finances on the team, the policy of trading stars for cash continued for more than a decade.

The Downhill Slide Continues

The next president of the Phillies was Lewis C. Ruch, who neither sought nor wanted the job. But once named, Ruch proved to be a capable and effective administrator who worked extremely hard to make the club respectable.

Ruch was born on a farm in 1862. His father died in the Civil War, and Ruch was raised in poverty. He had little formal education. As a youth he worked full-time as a farmhand. At the age of 21 he was earning $15 a month on a farm, plus 50 cents for each cord of wood he cut. Eventually, Ruch moved to Ravenna, Ohio, where he got a job in a hardware and farm implement store, earning $25 a month, and enrolled in a six-week business course in a school in Poughkeepsie, New York.

Ultimately, Ruch sold animal feed, then ended up in New York where he met Will Locke and William Baker. He worked at a freight transportation company, then an outdoor advertising company.

One day in 1913, Ruch received an urgent call from Baker. Locke was attempting to pick up an option he had to buy the Phillies, but several of his financial supporters had backed out at the last minute, and the deal was on the verge of collapsing. Locke and Baker were making a final attempt to arrange the sale. Could Ruch help out? He agreed, and later that day he was on a train from Brooklyn to Philadelphia to sign the papers and become part-owner of the Phillies.

One month after the transaction was completed, Locke died, and Baker was elevated to the club presidency. Ruch was named vice president, a position he held until Baker’s death in 1930 cast him into the role of president.

At the time of Baker’s death, he and Ruch owned the controlling interest in the Phillies. There was speculation that the club would be sold. A group headed by Ty Cobb was anxious to purchase it, as were several others. But Baker’s will stipulated that the club could not be sold. Ruch, who had originally retired in 1920 because of declining health, was hauled reluctantly out of retirement to direct the team.

Ruch became president on January 5, 1931, at the age of 69. At the time he had no plans to run the club, but when the board of directors passed him the reins, Ruch plunged enthusiastically into the job.

“Naturally, we are going to try and improve the Phillies,” said Ruch upon his appointment. The club had finished eighth in four out of the previous five seasons. Urging everyone to call him Charlie, the popular Ruch added, “From what I understand, it takes a healthy and active man to run the Phillies. I’ll do everything possible to bring about a winning club.”

Ruch vowed to spend every day from the start of spring training until the end of the season with the club. And he did, moving from his home in Brooklyn to Philadelphia, pumping his energy into the operation. Charlie engineered the end of a long contract dispute with slugger Klein, who staged a holdout that lasted through all of spring training in 1931. Klein signed a three-year contract for $45,000, a heavy sum for the Phillies at the time but far short of what many of Klein’s followers thought he was worth.

Under his administration, Ruch saw the Phillies progress to sixth place in 1931 and to fourth in 1932. But that was the only time the club finished in the first division between 1918 and 1949.

Ed Pollock in the Philadelphia Public Ledger praised Ruch as a sportsman and a “business man of proven acumen. He came into baseball as the president of a major league club at a time when finances were more important than pennants. The golden era had ended. He knew it. The players didn’t. He had to cut overhead expenses and at the same time satisfy the stars.”

After two seasons, Ruch, his health again failing, tendered his resignation as president on the advice of his physician. Charlie was then 71. Soon after he left the club, Ruch moved permanently to his winter home in Miami, where he died in 1937 at the age of 75. He was replaced by Gerald P. Nugent.

Born on October 25, 1892, in Philadelphia, Nugent was a football and baseball star at Northeast High School. After graduating, he took a job in the leather business and worked there until joining the Army in 1917. Nugent served in Europe in World War I, earning two citations for bravery.

After returning home, Nugent worked as a purchasing agent for a fastenings firm. In the early 1920s he met Mae Mallon, a secretary to and close friend of Phillies President William Baker and his wife. The two dated, and eventually Mallon introduced Nugent to her boss. Baker was so impressed with Nugent’s knowledge of baseball that he offered him a job as his assistant.

Nugent began work for the Phillies in 1925. Soon afterward, he and Mae were married. A year later he was named business manager, and in 1928 he joined the club’s board of directors. Long a baseball fanatic who devoured everything he could read on the subject, Nugent played a valuable role as Baker’s right-hand man. One of his moves was to purchase the contract of Klein for $7,500 from a minor-league team.

When Baker died in 1930, he willed 500 shares of Phillies stock to Mae and 700 shares to his wife. Two years later, at the age of 40, Nugent was elected president of the club when Charlie Ruch retired. Then, in 1934, Mrs. Baker died, leaving her 700 shares to Mrs. Nugent and the Nugents’ son, Gerald.

With the 1,200 shares that his wife and son now owned plus some stock he had previously bought himself, Nugent now controlled 51 percent of the Phillies stock. Mae, who had served under Ruch as treasurer and assistant secretary of the club, was added to the board of directors and named a vice president, the first woman to hold a position that high in the National League. Despite her lofty appointment, she refused to discuss it with the press. “Gerry does all the talking for this family,” she said.

Gerry did more than talk. He bought, he sold, he traded, he cajoled. No matter what he did, though, financial problems always seemed to intrude. At one point, Nugent had to put his stock as collateral to keep the team afloat. On at least one other occasion, he used his own salary to pay a debt, although he and Mae reportedly drew a combined salary of only $20,000. He even had to borrow sometimes so that he could send the team to spring training.

On the day he was named president of the Phillies, Nugent made an announcement to the press. “I will not trade or sell any of my key men, Bartell, Whitney, or Klein, no matter how attractive the figure or how promising the material offered. They are the nucleus of our club, the foundation from which we must build.”

Less than two years after making that statement, Nugent had not only traded that trio, but he’d swapped or sold an army of others. It was not so much a commentary on a man going back on his word as it was a statement on the dire straits to which the team had driven him.

In his 10 seasons at the helm of the Phillies, Nugent ruled over the sorriest period in the club’s history. It was an era of terrible teams, playing much of the time in a miserable ballpark with little success and equally little support from the fans. The combination of these formed a perpetually bleak financial picture in which Nugent struggled valiantly to make ends meet.

Gerry, it was said, was always just one step ahead of the sheriff. The team’s debts almost always exceeded its income. In the end that dilemma forced the beleaguered Nugent to relinquish control of his team.

Nugent was an astute businessman with an extremely thorough knowledge of baseball. “But no matter how good an operator you are,” he once said, “you have to have some luck.”

Nugent had none, and neither did his hapless charges. The Phillies never got above seventh place during Gerry’s presidency, finishing eighth six times and seventh four. The club seldom drew many more than 200,000 fans for the season, falling below that mark twice and going above 250,000 just once. Sometimes they attracted no more than 200 or 300 for a game.

It usually cost about $350,000 a year to operate the team, $250,000 of that going for payroll. Nugent figured that each paid admission brought in $1, which gave the club an annual income normally in the $200,000 range. That left an annual deficit of about $150,000. Nugent’s method for balancing the budget was simple. Nearly every year he sold off one or two of his best players.6

Nugent had the uncanny knack, though, of spotting obscure talent. He usually demanded such talent as throw-ins in trades. That’s how he got many fine young players. But once a player showed more than average ability, he was gone. Over the years, Nugent sold and traded away a virtual All-Star team, including Bucky Walters, Dolph Camilli, Claude Passeau, Johnny Moore, Ethan Allen, Kirby Higbe, Curt Davis, Morrie Arnovich, Spud Davis, Dick Bartell, Pinky Whitney, and Klein.

No one ever claimed Nugent didn’t know what he was doing. Gerry was regarded as one of the shrewdest traders in baseball. But the bill collectors always beckoned. And Nugent had to peddle his stars to raise cash. When Gerry sent Klein to the Chicago Cubs in 1933, he received three players and $65,000. Three years later, he got Klein back, along with $50,000.

The Phillies president inspired a lot of emotion with his wheeling and dealing. He was panned and pitied, admired and ridiculed. His constant trades were frustrating to the fans, who watched their heros parade in and out of Philadelphia with sickening regularity. His trades rarely helped the club, except at the bank.

For decades the Phillies had been hampered by the absence of Sunday baseball. The only times the team could expect to attract much of a crowd were Saturday afternoons and holidays. But in 1934, Sunday baseball was legalized in Pennsylvania. The attendance, 156,421 in 1933, jumped to 169,885 in 1934 and then to 205,470 the following year.

Nugent also managed to escape, at long last, from the motley problems of Baker Bowl. The $25,000 rent, plus $15,000 in taxes and $500 in upkeep that he paid each year were insurmountable costs. The right-field wall was so close to home plate that balls flew over it with sickening regularly. Even worse was the miserable condition of the obsolete structure. It was falling apart and had been given the nicknames “The Hump” and “House of Horrors.”

Although he had tried many times to break the 99-year lease signed long ago by his predecessors, Nugent finally succeeded in 1938 after threatening court action. The estate of Charles Murphy, former part-owner of the Phillies and Chicago Cubs and the owner of Baker Bowl, relented after Nugent agreed to make $25,000 payments over the next six years. The Phillies moved out of Baker Bowl in midseason in 1938, shifting seven blocks away to Shibe Park, home of the Philadelphia Athletics, at 21st Street and Lehigh Avenue.

The Phillies president had a reputation as an innovator. He was a strong supporter of interleague games. Nugent tried unsuccessfully to set up a farm system, too, naming Swarthmore College graduate Johnny Ogden, a former pitcher and minor-league executive, as the team’s first farm director. Ogden had one scout, Patsy O’Rourke. He introduced the knothole gang and Ladies’ Day to Philadelphia. And he proposed a Shaughnessy playoff plan in which the top four teams in each league would oppose each other over a two-week period to determine the pennant winners. Nugent thought this plan, used in the minor leagues, would generate a considerable amount of fan interest. Few others at the time agreed.

After a hunting accident in which Chicago White Sox pitcher Monty Stratton extinguished a budding career by shooting himself in the foot (ultimately resulting in the amputation of his leg), Nugent advocated placing a clause in contracts that would ban players from hunting. This idea also had little support.

While Nugent’s mind worked overtime, his players did little else but lose. Gerry, though, was the eternal optimist. “We’re on the upgrade and will have to be figured as a pennant factor this year,” he said in 1941. That year the club lost the most games (111) of any Phillies team in history. In fact, during Nugent’s ownership, the club had four of the Phillies’ seven worst seasons, at one point finishing last and losing more than 100 games in five straight seasons.

There was always some group or individual trying to buy the Phillies. Chocolate manufacturer Milton Hershey once offered $6 million with the idea of moving the club to Hershey, Pennsylvania. A California group wanted to buy the club for $5 million and move it to Los Angeles. Hall of Famer Bill Terry, then the Giants manager, and Philadelphia Eagles owner Alexis Thompson tried to put together a group to purchase the club. And there were other attempts by such potential buyers as Bill Veeck, Branch Rickey, Dan Topping, John B. Kelly Sr., Moe Annenberg, and the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce.7

In 1940 a group of the Phillies minority stockholders tried to oust Nugent and take control of the club. After a well-publicized battle that culminated in a stormy meeting of the team’s owners, the group lost its case because of insufficient support.8

In his Thanksgiving Day column in the Philadelphia Record the next day, Red Smith wrote: “Because holders of at least 51 percent of the Phillies’ stock agree he is a peachy fellow, turkey will grace the Nugent board this gladsome day, even though crow may be the piece de resistance for some minority stockholders.”

By this time, though, the Phillies’ debts were still mounting. And Gerry had new adversaries. National League President Ford Frick and the four owners making up the league’s board of directors were closing in for the kill.

In late 1942 it was becoming increasingly obvious that the National League wanted Nugent out, and that he had run out of options. In addition to that, World War II had decimated his team, leaving Nugent with no players left to sell. Reportedly, he owed the league $160,000 and was two years behind in rent at Shibe Park.

Frick moved swiftly, ousting Nugent and appointing a group from his office to run the Phillies while a new owner was sought. The new owner appeared almost immediately. Waiting in the wings to take over the club was William D. Cox, a friend of Rickey, then the president of the Brooklyn Dodgers, and the man Frick wanted to own the Phillies.

Meanwhile, Nugent sadly closed his office at Phillies headquarters in the Packard Building. “The scene,” wrote Ed Pollock in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, “was what you would expect at a funeral. Club employees looked like red-eyed mourners.”

Later, Nugent was named president of the Interstate League, a minor league in the Middle Atlantic area. He served in that position until 1952, then took a post as a stockbroker for a prestigious Philadelphia firm. Nugent died in 1970.

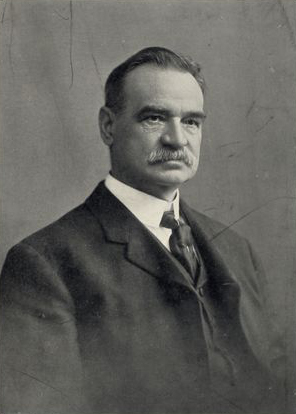

Former collegiate track athlete William D. Cox became owner of the Phillies at age 33 and immediately demanded changes in player conditioning, stating, “I want the team to run morning and afternoon.” (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

In just one short year as president of the Phillies, William D. Cox showed that he was a master at capturing headlines and creating turmoil. Probably no chief executive in the history of the franchise was ever as successful at turning the spotlight away from his team and onto himself. Cox, who was once described as “impatient, impetuous, and inexperienced,” was embroiled in one fracas after another.

A glib, convincing talker, Cox had the promotional instincts of a circus barker and a head substantially less knowledgeable for running a baseball team than he thought it was. Cox was an astute businessman. The trouble was he insisted on operating the Phillies with the same strict regimen with which he ran his lumber company.

He arrived on the scene with a considerable amount of fanfare in early 1943. Heading a 30-man syndicate, 20 of whose members were from Philadelphia, including future Phillies stockholders F. Eugene Dixon Jr. and his father, Cox outbid another syndicate led by John B. Kelly, Sr., for ownership of the team. The group put up $190,000 in cash, plus a $50,000 note for 4,950 of the team’s 5,000 shares. The National League eliminated one-half of the Phillies’ debt to it, and the Athletics’ Connie Mack forgave the amount owed him by the club.

Officially, the new group took title on March 15, 1943. At a press conference, Cox declared, “The Phillies will not want for an all-out show of energy, alertness and winning spirit.” He also said, “Whoever the manager is, there will never be an attempt on my part to interfere.” The statement would sound hollow a few months later.

Cox was 33 when he became president, the youngest man in that position in the major leagues. A native New Yorker, he was born in 1909 and grew up on swanky Riverside Drive, graduating from high school at the age of 15 and attending New York University and Yale.

After leaving Yale in his senior year, Cox worked for a New York bank, an investment firm, and finally a lumber company, which named him its president in 1936. Later, he founded his own lumber firm. In 1941 he became part-owner of the football New York Americans. Cox established a reputation for himself by running onto the field during one game to protest a referee’s call. His action earned his team a 15-yard penalty.

When Cox took control of the Phillies, he promised a fighting club. But the team had a limited number of bona-fide major-league players. And when spring training began at Hershey, Pennsylvania, there were only 14 players in camp.

Cox’s first big move was the appointment of Bucky Harris as the team’s manager. A veteran major-league pilot, Harris made some immediate improvements in the Phillies, and in the early part of the season the club even flirted with the first division.

The new president, who delighted in suiting up and practicing with the team, worked diligently to build the club into a winner. He acquired a number of respectable players, most notably Schoolboy Rowe, Babe Dahlgren, and Jimmy Wasdell. He bought a farm team at Utica, increasing the club’s minor-league holdings to two.

Overall, the Phillies of 1943 were vastly improved from the previous five years of eighth-place finishers. They wound up in seventh place with more wins (64) than any team since 1935. Fans responded favorably. Attendance (466,975) in 1943 not only was more than double that of 1942, but also was the highest for a Phillies team since 1916.

“Some of Cox’s maneuvers and statements were given a poor press and the public reacted unfavorably,” said Ed Pollock in the Evening Bulletin. “But at least he kept the fans talking about him and his ball club.”

Cox tried a lot of schemes to generate interest. On Opening Day, for instance, he set up a footrace before the game between the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Phillies. The Phillies won when Dodgers manager Leo Durocher ordered his players to jog and “save your running for the ballgame.”

The new owner was convinced that track and baseball had a lot in common. In pursuit of that notion, he hired a veteran track coach, Harold Anson Bruce, as the team’s trainer and physical-fitness director. Neither Harris nor the players were particularly thrilled by the intrusion.

But intrusions were part of Cox’s style. He often gave instructions to players, usually in conflict with Harris’s strategy. Cox made a habit of barging into the locker room before and after games, a practice generally frowned on. He was shocked when some of the writers advised him to stay out of the clubhouse.

During his reign, Cox feuded with National League President Ford Frick, with some of the other owners in the league, and even with officials of his farm team at Trenton, who protested to Commissioner Landis that he was raiding the club of its players.

In late July, climaxing a long and widening rift between the president and the manager, Cox leaked to the press that he was going to fire Harris. Bitter exchanges between the two men followed. The players were so irate that they refused to take the field for a game and returned to play only at the urging of Harris. At one point, almost as an aside, Harris told reporters that Cox had a habit of betting on the Phillies. The remark landed like an exploded bomb.

Through a letter written to him by a Philadelphia sports editor, Judge Landis, who had strict rules against gambling, learned what Harris had said. Quickly, the commissioner launched an investigation. It dragged on for months amid rumors, innuendoes, and speculation. Finally, on November 23, 1943, Landis announced that he was banning Cox from Organized Baseball for life. Despite a hearing on December 3 at which Cox defended himself, Landis’s verdict stood.

Cox, however, continued to participate in sports. In 1945 he became part-owner with Rickey of the Brooklyn Dodgers of the All-America Pro Football Conference. The team later merged with the New York Yanks and entered the National Football League.

He also vainly attempted to form a 10-nation soccer league. In 1966 he headed the New York entry in the North American Professional Soccer League. In the late 1960s he became general manager of that league’s San Diego Toros, and then executive vice president of the St. Louis Stars. He died in Mount. Kisco, New York, on March 28, 1989.

There’s Hope for the Future

In an era when most baseball teams were the part-time toys of owners whose main interests and occupations were elsewhere, Robert R.M. “Bob” Carpenter Jr. was a rarity. His only job was running the Phillies. He did it for 28 years, more than any president in Phillies history, pouring his energy and his family’s fortune into a team that most of the time lost money and finished in the second division.

In an era when most baseball teams were the part-time toys of owners whose main interests and occupations were elsewhere, Robert R.M. “Bob” Carpenter Jr. was a rarity. His only job was running the Phillies. He did it for 28 years, more than any president in Phillies history, pouring his energy and his family’s fortune into a team that most of the time lost money and finished in the second division.

The team had been purchased by Carpenter’s father, Robert R.M. Carpenter, a wealthy resident of Wilmington, Delaware, where he had married the sister of Pierre S. du Pont, and later became the president and part-owner of the mammoth E.I. Du Pont de Nemours Company. Various people had tried to buy the team, reportedly even Bill Veeck, whose father had been president of the Chicago Cubs, and who reportedly said he would stock the team with Negro League players if he became the owner.

But the senior Carpenter had made it known that if the Phillies ever came up again for sale, he would be interested in buying the team. When the Phillies lost their second owner in less than one year, Carpenter was contacted. Commissioner Landis was in no mood to play games with the floundering franchise. Connie Mack went to bat for the Carpenters, assuring Landis that they would be good for baseball. Others gave similar recommendations.

On November 23, 1943, the franchise was officially awarded to the Carpenters. The price tag was an estimated $400,000. The senior Carpenter put up the money, the junior Carpenter was installed as president, and the family would become the Phillies’ sole owners for nearly four decades

Born August 31, 1915, the year of the Phillies’ first pennant, Bob had been a football, basketball, and baseball star at Tower Hill School in Wilmington. Later, he attended Duke University, where he earned a varsity letter as an end on the football team.

Carpenter quit college before his senior year to get married. He took a job in the public-relations department of Du Pont, but, unhappy in that position, he left the job after two years. By this time, he was involved in sports activities in Wilmington. He promoted boxing matches and owned the rights to several fighters. He also raised champion Chesapeake Bay retrievers. And in 1937 he won the Delaware state badminton championship.

In the late 1930s, Bob had convinced Connie Mack of the need for a minor-league team in Wilmington. The two became partners in the Blue Rocks of the Interstate League. Carpenter was president, and Mack agreed to use the club as a farm team for his Athletics. Carpenter also became the owner of the Wilmington Blue Bombers, a professional team then in the American Basketball League, and he was the driving force behind the construction of a new stadium in that city.

Once he was installed as president of the Phillies, despite his team’s sometimes shoddy performances, Carpenter became a major power in the National League. While owners of other teams came and went with regularity, Carpenter was a pillar of consistency.

The highlight of Bob’s regime was the club’s 1950 National League pennant. He also presided over the signing of future Hall of Famers Robin Roberts, Richie Ashburn, and Mike Schmidt, as well as such stars as Dick Allen, Chris Short, Greg Luzinski and Larry Bowa. And he championed the city’s construction of Veterans Stadium.

Perhaps Carpenter’s chief contribution to the Phillies, though, was the dignity he gave to a flimsy franchise. Bob changed the image of the club, giving it the respectability it had for so long been lacking while finishing in the first division just once between 1918 through 1948.

During his 28 years as president, Carpenter’s teams finished over .500 12 times, placing in the first division nine times. The club either finished in or tied for first one time, second once, third twice, fourth five times, fifth seven times, sixth four times, seventh three times, and eighth six times. Over this period, Carpenter, spending nearly every minute of his waking hours working on Phillies business, had 12 managers.

Bob never took a salary, and he never expected to show heaping profits from the Phillies. “If anybody goes into this business for money,” he once said, “he should have his head examined.”

But Carpenter wasn’t anxious to lose money, either. He was a tough-minded businessman who described himself as “an awful skinflint” and who worked hard to achieve success with the Phillies. “I always wanted to make money,” he admitted, “because there’s no satisfaction in doing something if you don’t make a success of it.”

When Carpenter took over the Phillies, the franchise was in ashes, the result of the previous regimes. “All we had to start with,” said Bob, “was 25 second-division players and one minor leaguer named Turkey Tyson.”

The Phillies had a working agreement with one minor-league team (Trenton) and one scout. There was only one player on the roster who would be with the club three years later, young catcher Andy Seminick.

Although he was only 28 years old, at the time the youngest club president in National League history, with World War II at its height, Carpenter faced being drafted. So that he would have someone to run the club when that happened, his first move was to hire Herb Pennock as general manager.

Pennock was a former pitcher and a future Hall of Famer. He most recently was the farm director of the Boston Red Sox. He had been friendly with the Carpenters for many years, even to the point of taking Bob as a youngster on a road trip with him when he played for the New York Yankees.

In 1943 the Phillies had finished seventh, but having been eighth in the five previous seasons, Pennock and Carpenter formulated a plan to pull the club out of the National League dungeon. It would be a slow process, but the basic idea was to build a strong farm system.

“The first thing I want to do is build up the farm system,” said Carpenter at his first Phillies press conference. “We’re not going to beat anybody’s brains out by trying to get a good club right off the bat. But we are going to start working for one systematically.”

With Pennock teaching the young owner how to run a big-league baseball team, the two put their plan into action. Eventually, it became known as “the five-year plan.” Carpenter was drafted into the Army in March 1944 and served until January 1946, leaving Pennock to carry out the plan. Within four years, the Phillies had doled out bonuses amounting to $1,250,000. And the farm system was built up to a level where the club soon had nine scouts and working agreements with 11 minor-league teams.

During the early days of Carpenter’s presidency, the Phillies languished in eighth place. But after two years there, they climbed to fifth in 1946. The team that year was made up mostly of veteran players including Schoolboy Rowe, Emil Verban, Johnny Wyrostek, and Skeeter Newsome, who had been picked up from other teams. Their function was to make the club respectable until the youngsters arrived from the farms.

Meanwhile, Carpenter lavished huge sums on young players. A bonus of $65,000 went to Curt Simmons, $25,000 to Roberts, and lesser amounts to Ashburn, Del Ennis, Granny Hamner, Willie Jones, Stan Lopata, Bob Miller, Bubba Church, and others. Bob would stop at nothing to sign a player he thought would help the Phillies, often outbidding some of the wealthier teams like the Yankees, Red Sox and Cardinals.

To get Simmons, Carpenter even sent the entire Phillies squad to Curt’s hometown of Egypt, Pennsylvania, to face the left-hander’s local team. Simmons put on a dazzling show, nearly beating the Phillies. After the game, Carpenter treated all comers to a chicken dinner at the local fire hall.

There was nothing bashful about Carpenter when it came to opening his checkbook. As he later would demonstrate, that went for established players, too. Bob once offered the Cardinals $500,000 for Stan Musial. And he handed Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley a signed blank check for Duke Snider and Gil Hodges.

Of course, Carpenter’s big bucks didn’t always produce dividends for the Phillies. The club had some notorious flops: Tom Qualters, Tom Casagrande, Steve Arlin, Stan Hollmig, and Ted Kazanski, to name a few recipients of big bonuses.

Carpenter was, however, always attempting some positive change. He even tried to improve the club’s image by changing its nickname. In 1944, Carpenter held a public contest to pick a new name. The winner was Blue Jays. The name, however, was never registered with the league office as an official nickname and, having never gained much acceptance, it was dropped as a secondary nickname in 1948.

In 1946 Carpenter made headlines when he hired a woman scout, Edith Houghton. A former softball star on the widely heralded Bobbies and a former Navy officer, she is believed to have been the first female scout in baseball. One year later, Carpenter set up spring-training camp in Clearwater, Florida, after decades of moving around the country. More than 70 years later, the team was still there.

Pennock died suddenly in 1948, leaving Carpenter to run the club. When the senior Carpenter died a year later, Bob was strictly on his own. He acted as the club’s general manager for six years, until signing Roy Hamey in 1954. As GM, Bob traded away Harry Walker, who had won the batting championship just one year earlier. But he made the deals that gave the Phillies such key members of the 1950 team as Jim Konstanty, Dick Sisler, and Eddie Waitkus.

The high point of Carpenter’s administration came in 1950 when the players he and Pennock had planted on the farms ripened to produce a National League pennant. Sisler hit a 10th-inning game-winning home run to beat Brooklyn 4-1, and give the club the flag on the final day of the season. Relief pitcher Jim Konstanty won the league’s Most Valuable Player Award as a relief pitcher. The team, which averaged just 26 years old, justified the $2 million that Bob by then had pumped into a long-range development plan.

The Phillies lost the 1950 World Series in five games to the Yankees, and they never again came close to a flag during Carpenter’s reign. Some of the stars of the Whiz Kids never approximated their 1950 performances again. Eddie Sawyer, the manager who had been so popular a few years earlier, fell out of favor in 1952 and was fired. And the team in general did a downhill slide from which it never recovered, even though Sawyer was brought back as manager in 1958.

Philadelphia Phillies teammates carry Robin Roberts off the field following the 10-inning pennant-clinching game on October 1, 1950. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

The worst part of Carpenter’s regime occurred in the early 1960s. In 1961 the Phillies lost a major-league-record 23 straight games. Then in 1964, with Gene Mauch as manager and Johnny Callison, Allen, and Jim Bunning starring on the field, the first-place Phillies blew a 6½-game lead with 12 games left to play. It would be a disaster that was never forgotten by anyone who was around at that time.

One of the main criticisms of the Carpenter era was the team’s reluctance to sign black as well as Latin American players. It hadn’t helped the team’s image when manager Ben Chapman and some of his staff screamed racist comments at Jackie Robinson during his major-league debut year in 1947.

Actually, that view was badly mistaken as the team had signed its first African-American, a player named Ted Washington of the Philadelphia Stars, in 1952. Others were signed in the years shortly thereafter, although the first black player to perform in an actual Phillies game did not occur until John Kennedy took the field in 1957.

It was sometimes said that Roy Campanella, a Philadelphia native, would have preferred the Phillies to the Dodgers. But he wasn’t the only great star the Phillies could have but didn’t sign. Al Kaline and Carl Yastrzemski could have worn Phillies uniforms, but got away. So did Hank Aaron.

Carpenter was always somewhat preoccupied with big, strapping pitchers who could throw hard. He packed his major- and minor-league rosters with pitcher like Short, Bob Miller, Jack Meyer, Jim Owens, Don Cardwell, Dick Farrell, Jack Sanford, Dallas Green, Art Mahaffey, Ray Culp, Dennis Bennett, and Rick Wise. One such pitcher the Phillies developed but let go in an ill-advised trade was Ferguson Jenkins, who became one of the outstanding hurlers in the major leagues and a Hall of Famer.

It was just the reverse situation with Roberts. The great right-hander, often rated by Carpenter as his number-one player, performed brilliantly year after year in Philadelphia, at one point winning 20 or more games in six straight years. Repeatedly Carpenter turned down trade offers for Roberts. He finally did move him, reluctantly and only after it had become apparent that Roberts and new manager Gene Mauch couldn’t get along. But he refused $75,000 from one club, instead accepting $20,000 from the Yankees so that Roberts could play for a pennant contender.

Carpenter was like that. A generous man, he loaned money to many of his players who wanted to buy businesses or homes or who were simply short of cash. And he often took care of their expenses when they were ill or had problems. When Waitkus was shot in 1950 by a deranged woman, Bob ordered the best available medical care. Then he paid for a winter of rehabilitation in Florida for Waitkus and trainer Frank Wiechec, one of the first full-time trainers in baseball.

Carpenter could be a strict president. He was opposed to his players enjoying too much nightlife. When the postgame habits of some of the Phillies seemed to become a problem in 1954, Bob and Hamey hired private detectives to follow them. The tactic backfired when infielder Granny Hamner discovered that he was being trailed home after a game. Hamner called police who arrested the detective. Hamner exploded in a well-publicized tirade, demanding and subsequently getting an apology from Carpenter.

Bob could get mad himself. One famous outbreak occurred at spring training in 1949. The Boston Red Sox were visiting Clearwater for an exhibition game. Expecting to see the mighty Red Sox sluggers, a large crowd poured into the ballpark. Boston manager Joe McCarthy, however, had left Ted Williams and Vern Stephens home. When Carpenter learned this, he was irate. Bob grabbed a microphone and announced to the fans that they could have their ticket money refunded. The gesture merely served to infuriate the Red Sox, especially McCarthy. A near-brawl followed in which several Red Sox and Phillies officials almost engaged in a fistfight.

Carpenter could throw his weight around when necessary. When A.B. “Happy” Chandler’s contract as baseball commissioner came up for renewal, Bob led the fight to oust him. He also led the drive to install National League President Ford Frick as commissioner. Carpenter’s side won both battles.

Carpenter was heavily involved in the demise of Connie Mack Stadium (the former Shibe Park) as a major-league ballpark and the emergence of Veterans Stadium. In 1954, although he wasn’t anxious to do so, Bob bought Connie Mack Stadium when the Athletics left for Kansas City. He paid $1,657,000 for a ballpark that in 1908 had been built for $315,248.69. Soon afterward, he began a campaign for a new ballpark.

Carpenter sold Connie Mack Stadium in 1964 to Philadelphia Eagles owner Jerry Wolman for a meager $600,000. The Phillies continued to play there, while the campaign for a new ballpark staggered along. Finally, with Carpenter, the owners of the Philadelphia Eagles, and others prodding the city, a new site was selected at Broad Street and Pattison Avenue in South Philadelphia. Costing some $52 million, the city-owned ballpark that seated 55,371 for baseball officially opened as Veterans Stadium in 1971.

By then the Phillies had run the gamut from pennant winner to doormat to pennant contender to mediocrity. Carpenter’s team had been on a frustrating roller-coaster. On November 22, 1972, Bob announced that he was stepping out as president. His son, Ruly, became the chief executive, and Bob took the position of chairman of the board.

Carpenter died at his home outside of Wilmington on July 8, 1990. He was 74.

Daredevil Karl Wallenda crosses a high-wire atop Veterans Stadium on August 13, 1972, in Philadelphia. (Courtesy of the Philadelphia Phillies)

In his nine years as president of the Phillies, Robert R.M. “Ruly” Carpenter III watched his team and the sport it played change completely.

Ruly was 3 when his father took over the team. He was 10 when the team won its second National League championship, but by the time he enrolled in Yale University, the team had reached bottom.

At Yale, Ruly was a two-way end on the football team and captained the baseball team, on which he pitched and batted .350. He was also teased constantly by his classmates and friends about how bad his father’s baseball team was.

Ruly had gone to New Haven with the idea of pursuing a career in law, but he changed his mind while at school. “The teasing and criticism from my teammates and classmates in college convinced me that I wanted to do something about the Phillies. It was kind of a challenge,” he said.

After Carpenter graduated from Yale, he took courses in business administration at the University of Delaware and served as the university’s assistant baseball coach. In 1963 he joined the Phillies in the accounting department. By the spring of 1964, he and then-scout Paul Owens worked together, evaluating the talent on the lowest minor-league teams in the Phillies chain. Later, Carpenter said he enjoyed player development more than anything else in baseball.

“His dedication and intensity were so great, I was certain once he got experience, he would make a fine baseball executive,” Owens said.

Both Owens and Ruly could see something was wrong with the Phillies’ farm system. In 1965, at Ruly’s urging, Owens was named farm director. Ruly became his assistant. The roots had been planted to turn the team around by developing players instead of trying to trade for them.

In June 1972 Owens replaced John Quinn as general manager. One month later, he fired Frank Lucchesi and named himself field manager, explaining that he had to see firsthand what his team was all about. Ruly agreed totally with that philosophy. The Phillies won only 59 games in 1972.

Ruly, at age 32, assumed the presidency after the 1972 season. When he did, the Phillies had a quartet already working for the club who would become the longest-serving employees in the team’s history. Public relations director Larry Shenk had been hired by the team in 1963 and would hold that position until he retired in 2007. Chris Wheeler had joined the Phillies’ PR staff in 1971, then became a broadcaster in 1977, holding that post until 2013. Harry Kalas had also joined the team in 1971, and would be the team’s iconic play-by-play announcer until 2008. And public-address announcer Dan Baker would start in 1972 and after 46 years was still at work in 2018, the second-longest PA stint in baseball history.

When Carpenter took over, however, the Phillies’ future did not seem bright. About the only thing they had going for them was the result of a trade. In the last major deal made by general manager Quinn, who had joined the team in 1959, he talked the Cardinals into giving him Steve Carlton for Rick Wise. It was a deal that would forever stand as one of the best the Phillies ever made.

But there were other problems. Before that season, baseball had undergone a massive change, and the Phillies were hugely affected. When Curt Flood was traded to the Phillies in 1970, he challenged the reserve clause, which bound a player to a club as long as it wanted him. The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Eventually, free agency was born.

Ruly hated it all. He admitted that things had not been right in the past, but that now they had swung the other way. At first he refused to get into any auctions for players, preferring instead to sign his own stars like Schmidt and Greg Luzinski to lucrative long-term contracts. He believed the Phillies had developed the players and that they should enjoy the fruits of their labor. Bowa, Bob Boone, and Dick Ruthven were among others who had grown up through the Phillies farm system.

Eventually, they all took major roles on the team. And from 1976 through 1978, under manager Danny Ozark and with Owens adding some high-ranking players like Garry Maddox, Manny Trillo, and Tug McGraw in trades, the Phillies won three National League East titles. But they lost in the League Championship Series each time. Then in 1979, the Phillies signed Pete Rose.

That proved to be a brilliant move. In 1980, led by Rose and the provocative manager Dallas Green, the Phillies won the East Division, and the League Championship Series in a thrilling match with the Houston Astros. They then won the first World Series in club history, beating the Kansas City Royals in six games with Carlton winning two games and McGraw winning one and saving two.

“It was the greatest day of my life, more awesome, more emotional than I ever dreamed it would be,” Carpenter said. But that was one day of happiness. There were too many other days of misery. “It isn’t fun anymore,” Ruly said in 1981, the year of a players strike.