Tom Seaver

As baseball has often been described as a game of numbers, fans, reporters, and students of the game would most certainly recognize the preceding list of significant digits. These were the career accomplishments forever linked to the respective immortals Pete Rose, Hank Aaron, Nolan Ryan, Cy Young, and Ty Cobb. To that list, another number should be added to commemorate a feat of equal important to longevity in base hits, home runs, strikeouts, wins, and batting average.

98.8.

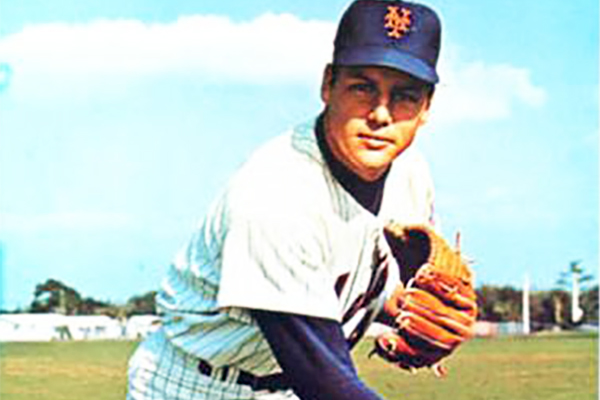

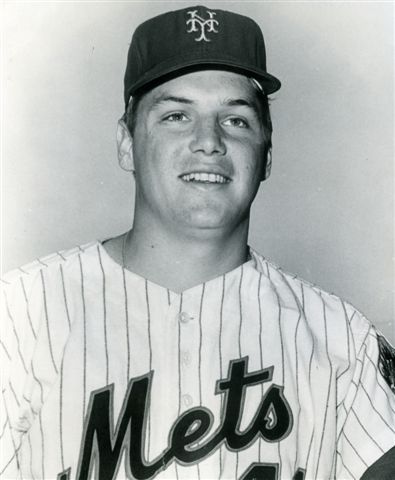

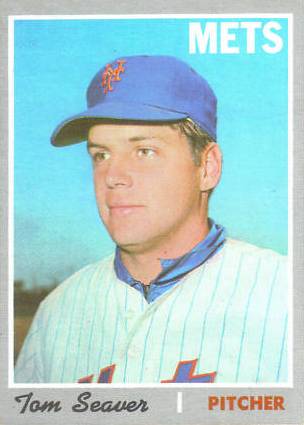

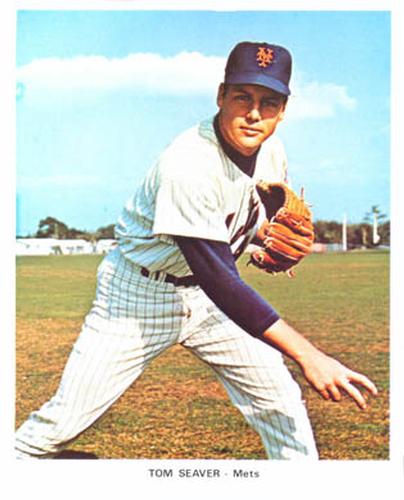

On January 7, 1992, that was the percentage by which Tom Seaver was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. To that time, no player ever received a higher approval rating by the Baseball Writers Association of America. Few players were ever more connected as a “franchise” player than Tom Terrific with the New York Mets. No member of the team was as intricately associated with their meteoric rise from cellar dwellers to world champions.

Seaver was an immediate success upon arriving in New York in 1967. His miracle season of 1969 was highlighted by the game of his career against the divisional rival Chicago Cubs. He continued to pitch brilliantly in the 1970s, fanning 10 consecutive Padres in a game, collecting 200 strikeouts for nine straight seasons, and becoming the first right-hander win three Cy Young Awards. In 1977 an ugly contract squabble led to what became known as the Midnight Massacre, a trade to the Cincinnati Reds that devastated the Mets and drove countless fans away from Shea Stadium. After five years of exile in the Queen City, Seaver returned to Queens in 1983. Although he wore socks of a different color scheme toward the end of his career, he saved his final crowning achievement for the New York fans to enjoy.

George Thomas Seaver was born on November 17, 1944, in Fresno, California. His mother, Betty, was a homemaker and his father, Charles, was an executive with the Bonner Packing Company, which harvested and shipped raisins to all corners of the country. The Seavers were an athletically minded family. Charles had been a Walker Cup golfer in his youth, while swimming, volleyball, and surfing were also represented in the family.

Seaver joined the North Rotary team in the Fresno Little League at the age of 9 as a pitcher and outfielder. Within three years, he had pitched a perfect game while batting a robust .540. Later, Seaver pitched for Fresno High, a school that had already graduated pitching luminaries Jim Maloney, Dick Ellsworth, and Dick Selma.

“Even … in high school, Tom was a thinking pitcher,” remembered Selma, later a teammate of Seaver’s on the Mets. “He knew how to set up a hitter by working the corners of the plate and the batter would usually pop the ball … for an easy out.”1

After graduating from high school in 1962, Seaver registered at Fresno City College while working in the raisin trade. While a student, he also put in training time in the Marines. Scouts had begun to notice his pitching repertoire after his second year, when he won 11 consecutive games while setting numerous school strikeout records. So did Rod Dedeaux, the legendary baseball coach who led the University of Southern California to 11 College World Series titles. Dedeaux asked Seaver to join the Trojans for his junior year. To prove his reputation and earn his scholarship, Seaver went to Alaska to pitch for the semiprofessional Goldpanners.

At USC in 1965, Seaver went 10-2, striking out 100 batters in 100 innings. Although only one organization scouted Seaver in 1965, the Atlanta Braves wasted no time the following year, drafting him in January and signing him a month later. The Braves had been Seaver’s team of choice growing up in Fresno. Hank Aaron was his hero, and as he told interviewer Marty Appel, “I loved their uniforms, and I loved their hitters … Aaron, Eddie Mathews, Joe Adcock.”2

But as much as he loved the tomahawk, Seaver never wore it for an inning of his professional career. Major-league rules prevented any organization from signing a college player while his season was in progress. Although Seaver had yet to pitch in 1966, the USC season was under way when the Braves signed their right-handed prospect. Commissioner William Eckert voided Seaver’s contract with the Braves on March 2. If other teams matched Atlanta’s offer of $51,500, they would participate in a lottery for Seaver’s services. Three teams — the Indians, the Phillies, and the Mets — stepped forward with contractual offers. The lottery was conducted on April 3 as each organization had its name thrown into a hat. Would Seaver join Sam McDowell and Sonny Siebert in Cleveland’s rotation? Would he emerge as Philadelphia’s third starter behind Jim Bunning and Chris Short? Neither. The winning paper selected belonged to the losingest team in baseball, the Mets.

Seaver earned a bonus contract worth $10,000 more than the Braves’ offer, and began his professional career with Jacksonville. Pitching for the Mets’ top farm club, Seaver went 12-12, throwing four shutouts and fanning 188 International League hitters. He married his high-school sweetheart, the former Nancy Lynn McIntyre, on June 6. Jacksonville manager Solly Hemus was overwhelmed by his pupil’s talent and poise, insisting that his “35-year-old head attached to a 21-year-old body” was ready for prime time.3 Earl Weaver, then managing the Orioles’ affiliate at Rochester, agreed with Hemus from the visiting dugout: “It was apparent in Tom Seaver’s pro debut that he was ready for the majors. He had an excellent fastball and slider and he put them precisely where he wanted to, in and out on the black of the plate, mostly knee-high. After Jacksonville beat us, I phoned [general manager] Harry Dalton and said that Seaver was going to be sensational and the Orioles could give up a piece of the franchise and do well to get him.”4

Having never won more than 66 games or finished higher than in ninth place since coming into existence in 1962, the New York Mets underwent a 19-player overhaul under new general manager Bing Devine. One of the new faces in New York in 1967, true to Hemus’s prediction, was Tom Seaver. His baptism into the major leagues for manager Wes Westrum occurred on the second day of the season, April 13, as he yielded six hits to the Pittsburgh Pirates in 5⅓ innings with eight strikeouts and four walks. Seaver gave up just two runs as the Mets won, 3-2, but Chuck Estrada was the winning pitcher. By July Seaver had amassed a record of 6-4 with a 2.60 ERA, commanding sufficient respect to merit a spot on the National League All-Star team. This midsummer classic, played at Anaheim Stadium, was deadlocked after 14 innings. After Tony Perez homered to give the senior circuit a 2-1 lead, manager Walter Alston summoned Seaver to face the American League in the bottom of the 15th. On that night, a nationally televised audience was introduced to a rookie with a 35-year-old head; Seaver got Tony Conigliaro to fly out before walking eventual Triple Crown winner Carl Yastrzemski. After Bill Freehan flied out, Seaver ended the game by striking out Ken Berry on a high fastball. Tom Terrific was bound for greatness.

Seaver rewrote the Mets’ pitching record book in 1967. It wasn’t hard given the team he was on 10th and last in the National League with 60 victories and 101 defeats, but he has since held his grip in most categories. His 16 victories, 18 complete games, 170 strikeouts, and 2.76 ERA in 1967 set new marks for the club. He also became the first Met in history to earn the National League Rookie of the Year Award. Even the normally reticent Hank Aaron expressed his admiration for Seaver. “You’ve got a nice pitch, kid,” he told Seaver. “Good fastball, nice curve.”5 The California kid was already drawing comparisons to Christy Mathewson as the pre-eminent righthanded pitcher of his generation to play for a Gothamite team. As for Bill Bartholomay, whose Braves were 0-4 against Seaver in 1967, all he could muster in light of the contract nullification was “I get sick every time I watch him pitch.”6

As Mets broadcaster Howie Rose later reminisced to author Bruce Markusen, Seaver brought a sense of hope that was absent from previous Mets teams. Before he joined the Mets, Rose said, “There was this inescapable culture of losing, and at least among their fans, a growing sense of losing was going to be something permanent.” He added, “People who watched [Seaver] as a rookie got the sense that they had finally developed a player who was capable of doing special things, and therefore capable of helping the Mets achieve some pretty good thing of their own along the way.”7

Seaver did not fall prey to the sophomore jinx in 1968, winning 16, fanning 205, and committing only one error all season. He could sense that greatness was around the corner for the Mets:

“We pass over 1968 too quickly,” Rose said. “That was the season the executives were getting the pieces together … getting Tommie Agee to play center field, getting Jerry Grote along as the catcher, getting the pitching staff together. They could see there was a Seaver, Ryan, Jerry Koosman, Grote, (Bud) Harrelson, and getting Gil Hodges.”8

If the Mets were destined for immortality in 1969, it was certainly not evident from their Opening Day performance on April 8. Broadcaster Ralph Kiner remembered Seaver “getting knocked out of the box” by the expansion Montreal Expos, who defeated the Mets, 11-10. The ensuing weeks were no kinder to the Mets. Injuries, slumps, erratic defensive play, and a lack of experience all prevented them from advancing beyond the second division of the National League East. In May, Hodges even told reporter Jack Lang that his hitters “looked like wooden soldiers.”9

On May 21 in Atlanta, Seaver shut out the Braves to improve his record to 6-2. The Mets, meanwhile, evened their record at 18-18. To Seaver the milestone was no cause for celebration. He defined the .500 mark as “neither here nor there” and said that his teammates’ embrace of mediocrity “isn’t going to get us very close to a pennant.”10 As Ralph Kiner chronicled in his 2005 memoir, Seaver’s role as a motivator was crucial for the Mets’ renaissance in 1969.

“Tom Seaver was the driving force behind the players, always pushing the team to be better than they were, never letting them settle,” Kiner reminisced.11 He might not have remembered the legacy he imprinted on Seaver at a far younger age. At the Bing Crosby Pro-Am Golf Tournament, Charles Seaver approached Kiner and said he would appreciate an autograph for his son, who aspired to become a baseball player. The retired Pirates outfielder gladly signed a school photograph: “To Tom, work hard and good luck, Ralph Kiner.”

Diligence and luck, along with talent, were essential ingredients in the Mets’ 11-game winning streak in late May and early June. For every player, there was a different highlight that augmented their confidence, but for Seaver, it was an extra-inning clutch hit to win the contest on June 4 against the Dodgers.

“We were in a scoreless game until the 15th inning. Then Wayne Garrett hit a ball up the middle with [Agee] on second. There was going to be a close play at the plate. Willie Davis came charging in and the ball was under his glove. The winning run scored. There was real electricity. I remember going into the clubhouse and making eye contact with Grote,” Seaver said. He described the experience as “the last ounce that tipped me over into believing we could win.”12

By now, the Mets were in second place behind the Chicago Cubs. When he defeated the Padres on June 14, Seaver improved his record to 10-3. The Mets’ mound excellence behind Seaver, Jerry Koosman, Don Cardwell, and rookie Gary Gentry was renowned throughout the league. Seaver claimed that a renewed collective excellence in the field was equally important, “especially up the middle with Grote, Harrelson, and Ken Boswell, and Agee in center field.”13 The Mets upgraded their offense on June 15 when they acquired Donn Clendenon in a trade from Montreal. A veteran first baseman who studied law in the offseason, the sardonic Clendenon complemented the more cheerful Ed Charles across the diamond. In a tense racial period the year after the assassination of Martin Luther King, both clubhouse leaders on the Mets were African Americans. In Seaver’s estimation, that hardly seemed to matter to his teammates, black or white. With sterling pitching and defense, solid offense, a hardnosed manager, clubhouse chemistry, and confident players, the Mets had no reason to look back. Only the Cubs stood in their way of a division title.

All of these factors set the stage for what was arguably the strongest game Seaver ever pitched. It certainly is the best-remembered Seaver game, even more than his no-hitter pitched for Cincinnati in 1978.

The Cubs, leading the division by four games, were visiting the Mets at Shea Stadium on July 9, 1969. Among the 50,709 exuberant spectators packed into the stands was Charles Seaver, who had flown from California on business. The younger Seaver had not even been certain he could pitch that evening due to a sore shoulder, but his pitches early on surpassed even his own perfectionist standards. While the Mets amassed a 3-0 lead in the third inning, no Chicago batsman even reached base. At this point, pitching coach Rube Walker broke one of baseball’s cardinal rules, turning to Hodges and confiding, “Gil, I see something special out there. He’s razor sharp. He’s going to throw a no-hitter tonight.”14

“Emotionally, I was fully aware of what was going on,” remembered Seaver. “I came to bat and got this incredible standing ovation [in the sixth inning]. I felt as if I was almost levitating.”15 It mattered not that Seaver struck out. Eighteen Cubs batters had strode to the plate. Eighteen returned disappointed to the dugout. The Flushing faithful were glued to the edges of their seats both at Shea and on WOR-TV as Seaver continued to baffle the Cubs. Don Kessinger led off the seventh inning by flying out to left. Glenn Beckert flied out the opposite way before Billy Williams ended the inning with a groundout to third base. Seaver was equally masterful in the eighth inning. After Ron Santo flied out to center field, Tom Terrific fanned Ernie Banks and Al Spangler for his 10th and 11th strikeouts of the night. Twenty-four up, 24 down.

Shea Stadium, courtesy of Jim Bunning in 1964, had been the site of the first National League perfect game since 1888. Now it seemed like the perfect place for a repeat as Seaver took the mound for the top of the ninth. The inning began with a gasp as Randy Hundley led off with a line drive to the pitcher’s mound. Seaver trapped it and tossed Hundley out at first base.

Enter Jim Qualls.

Of any Cubs hitter, Qualls had hit “the only hard-hit balls of the night.” Seaver had already yielded two sharply hit balls to the obscure rookie outfielder. The pitcher mused that “if anybody gets a hit off me tonight, it would be this guy.”16 Seaver was right. He pitched the left-handed hitter away, and Qualls unleashed a clean base hit to shallow left field. The perfect game was over. The “imperfect game” became a part of the Mets lexicon.

A consummate professional, Seaver retired the last two batters and threw the first of his club-record five one-hitters. The Mets won, 4-0, defeating the front-running Cubs in the most crucial game of the season to that point. The baseball universe knew that the Mets were for real.

Although the Mets and Seaver faded in late July, the third-place Cardinals could not capitalize on their errors to overtake them in the standings. Then, in August, the Mets were dealt a grueling test of endurance: 20 games in 20 days, including four doubleheaders against three California teams. While some teams would have capitulated to the exhausting schedule and the transcontinental flights, the Mets went 15-5. As the winner of three games during the Golden State marathon, Seaver had improved his record to 19-7. He had not lost since August 5, when he dropped a decision to Cincinnati’s Gary Nolan, and would be perfect in his final six decisions. The Mets took sole position of first place on September 19, and captured the division title five days later.

As the staff leader with 25 wins, Seaver was given the starting assignment for Game One of the National League Championship Series against the Atlanta Braves. But had the miracle run its course? The Braves, behind their ace Phil Niekro, jumped Seaver for five runs on eight hits in seven innings. Trailing by one in the eighth, the Mets rallied for five runs to preserve the victory for Seaver. The Mets easily disposed of the heavily favored Braves by winning the next two games, claiming a spot in the World Series against Baltimore.

As the staff leader with 25 wins, Seaver was given the starting assignment for Game One of the National League Championship Series against the Atlanta Braves. But had the miracle run its course? The Braves, behind their ace Phil Niekro, jumped Seaver for five runs on eight hits in seven innings. Trailing by one in the eighth, the Mets rallied for five runs to preserve the victory for Seaver. The Mets easily disposed of the heavily favored Braves by winning the next two games, claiming a spot in the World Series against Baltimore.

Despite the best overall record in the National League, the Mets remained the heavy underdog in the World Series against the 109-win Orioles. The O’s were an older, more experienced club with most of the same personnel who had won a world championship in 1966, when the Mets were still giddy over not losing 100 games for the first time. In the minds of many, the success of the Miracle Mets could not erase the image of Jimmy Piersall running backward around the bases or Marv Throneberry’s disqualified triple on the grounds that he failed to touch first or second base. Earl Weaver, the first-year manager of the Orioles, was not convinced that this would be another four-game sweep for the Birds. “I didn’t think for a minute that the so-called ‘Miracle’ Mets would be easy opponents in the Series,” he said in his autobiography. Their pitching was too good, particularly that of Tom Seaver and Jerry Koosman, whom I managed in the minors.”17

Yet after one batter in Game One, the skeptics appeared correct, as Baltimore’s Don Buford unleashed a home run to lead off the bottom of the first against Seaver. The Mets found themselves in worse trouble by the fourth inning, when Seaver allowed four hits, including a double to Buford, to bring in three additional runs. The Mets, meanwhile, managed to produce only one run against Baltimore starter Mike Cuellar. Compounding matters, a journalistic rumor began to circulate that if the Mets won the World Series, Seaver would purchase a full-page advertisement in the New York Times urging the United States to withdraw from Vietnam. Though the statement was without an ounce of truth, the baseball establishment was shocked that one of its brightest stars could lend his name to a controversial and divisive cause. Although Seaver could not dodge the bats of Cuellar and his teammates, he circumvented the Vietnam issue by stating that he “did not want to be used for political purposes.”18

As it happened, Seaver’s next turn to pitch was Moratorium Day, a nationwide day of protest against the conflict in Indochina. Seaver, like countless others entering Shea Stadium, was asked to don a black armband as part of the demonstration. True to his word, he refused. Game Four was a rematch of the opener, with Cuellar and Seaver facing off again. Only now, the Mets had won two straight and Seaver looked almost as good as he had against the Cubs in June. He threw eight shutout innings and held a one-run lead on Clendenon’s second-inning home run. The ninth inning was more cumbersome, particularly as Seaver faced Baltimore opponents named Robinson. A Boog Powell single advanced Frank Robinson from first to third, and Brooks Robinson hit a wicked liner to right that only a stupendous catch by right fielder Ron Swoboda kept as a game-tying sacrifice fly instead of a go-ahead triple. Despite losing the lead, Gil Hodges left Seaver in to pitch the 10th inning. In the bottom half of the frame, Grote led off with a double against 39-year-old accountant Dick Hall. Rod Gaspar pinch-ran. Pete Richert was called from the bullpen to face the left-handed J.C. Martin, who batted for Seaver. Martin bunted to the right of the mound, and Richert’s throw glanced off Martin’s wrist, then bounced into the outfield, allowing Gaspar to score from second base. Seaver got his only career World Series win and the next day the Mets completed one of the most stunning world championships in history.

One month shy of his 25th birthday, Tom Seaver was at the height of his game. He was a leader and motivator on a talented Mets team which, in its eighth National League season, defied all expectations. He led the league with 208 strikeouts while limiting opposing batters to a 2.21 ERA. He won the National League Cy Young Award and the Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year title, the only Met ever so honored. He finished a close second to Willie McCovey in the MVP voting (265 to 243), after no previous Met had even got near the top 10. Seaver took part in a ticker-tape parade described by the Wall Street Journal as a more colossal celebration than V-E Day, Charles Lindbergh’s flight, and the return of the Apollo astronauts, all rolled into one.19 He appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show, performed at a Las Vegas supper club, and purchased a Victorian farmhouse in Greenwich, Connecticut. However, if Seaver himself read this list of accomplishments, he probably would have added, “But you forgot one thing. I’m the only Mets pitcher who’s lost a ballgame in the World Series.”20

Seaver would not rest on his laurels. The next season, he led the league with a 2.81 ERA and 283 strikeouts. Nineteen of those whiffs were recorded on April 22 against the Padres, including the last 10 San Diego batters he faced, a feat still unmatched. In 1971 he had as good a year as he ever enjoyed in baseball statistically, setting personal marks with 289 strikeouts and a radiant 1.76 ERA to lead the NL in both categories. His 20 wins were four behind Ferguson Jenkins’s total and the Cubs hurler took the Cy Young Award by 36 votes.

Tragedy overshadowed New York’s 1972 season in spring training when Gil Hodges died of a heart attack after a round of golf. Seaver paid an eloquent tribute to his late manager, affirming that “Gil is here inside each man, and he will be here all season. The man made a terrific impact on this ballclub.”21 Under new skipper Yogi Berra, Seaver led the club with 21 wins and 249 strikeouts. In his first six seasons 1967-72, Seaver led all National League pitchers with 116 wins and 1,404 strikeouts. Only Bob Gibson’s 2.42 ERA was better than Seaver’s 2.44.

In 1973 Seaver became the first pitcher to win the National League Cy Young Award without winning 20 games. As was the case with his first Cy Young, it was evident to anyone associated with the Mets that he was indeed their franchise player. Off to a promising start, the Mets ended April atop their division with a record of 12-8. However, mediocrity soon prevailed, after injuries to key players Jerry Grote, Cleon Jones, Bud Harrelson, and even Willie Mays. By June 25 the Mets languished in the divisional basement, 8½ games behind the Cubs. Still, the second-place Montreal Expos were only two games ahead of the Mets. “It was the kind of year that nobody seemed to want to win,” Seaver later remarked.22

The Mets entered July with a losing record, but so did four of their opponents in the “NL Least.” Gloom prevailed in Flushing as the Mets posted a 32-49 record from May through July. When rumors circulated that Berra would be fired, chairman M. Donald Grant rushed to the manager’s rescue. He affirming that Berra would not be fired “unless public opinion demands it.”23 The New York Post capitalized on the remark, conducting a poll to ask which Mets executive should be fired, Berra, Grant, or general manager Bob Scheffing. Only 611 of the more than 3,000 ballots cast found Berra culpable for the Mets’ futility.

Amid the despair there was one bright hope, embodied in a blue and orange pinstriped uniform emblazoned with the number 41. After defeating the Phillies on Opening Day, Seaver’s consistency outshone that of his teammates. When the Mets were 30-35, Seaver was 7-3. In a three-week stretch of late May and early June, Tom Terrific was responsible for the only four wins registered by the Mets. In one of those games, on May 29, he struck out 16 San Francisco Giants and was named National League Player of the Week. When Berra rhetorically asked sportswriter Terry Shore where the Mets would be without Seaver, the writer replied, “In last place with a 17-game losing streak and certainly out of any division race.”24 Seaver was particularly effective after Grote returned from the disabled list in late July.

Although the Mets remained in last place through late August, Grant ignited confidence in a clubhouse meeting in which he reminded his players that they could win their division if they believed in themselves. Tug McGraw’s repeated exclamation of “Ya gotta believe!” drove Grant from the locker room and a rallying cry was born. Berra echoed Grant’s sentiments in observing the divisional race. He remarked that every team had a hot streak except the Mets, adding, “It ain’t over ’til it’s over.”25

Berra, Grant, McGraw, and company were right. The Mets surged in September, winning 21 of their last 29. On September 21 Seaver defeated the Pirates to even the club’s record at 77-77, which in their mediocre division was good enough for first place. Seaver took the mound again on October 1 and defeated the Cubs, 6-4, to win his 19th and final victory of the regular season and clinch the division title. Until the San Diego Padres won their division in 2005, no National League team finished first with a worse record than the 1973 Mets’ 82-79. For his part, Seaver led the league with 251 strikeouts and a 2.08 ERA. He completed 18 games, tying Steve Carlton for the league lead.

Yet there was some concern about Seaver’s shoulder and it took a workout at Shea Stadium two days after the clinching for him to be pronounced as fit to start the NLCS opener against the powerhouse Reds, winners of 17 more games than the Mets and with an 8-4 mark against New York during the season. Cincinnati, which had represented the National League in two of the previous three World Series, had a lineup that was a veritable Murderers Row: Even if the Mets succeeded against Pete Rose, Joe Morgan, and rookie Dan Driessen in one inning, they still had Tony Perez, Johnny Bench, and Ken Griffey due up the next inning. Facing Jack Billingham, a distant relative of Christy Mathewson, Seaver fanned 13 and walked none in the NLCS opener; he also benefited his own cause by doubling in a run in the second inning. Nevertheless, the ghost of Big Six smiled upon his cousin and the Big Red Machine in the latter frames of the game. Rose tied it in the eighth with a home run and Bench’s ninth-inning blast won the game, 2-1.

The Mets came right back from the disappointment and won the next day on Jon Matlack’s two-hit shutout. The Mets took Game Three at Shea despite a nasty brouhaha between Rose and Bud Harrelson. Seaver, along with Mays, Berra, Cleon Jones, and Rusty Staub, went out to left field to restore order after fans at Shea pelted Rose in left field with everything from paper cups to a whiskey bottle. The Mets won the game, but Rose exacted some revenge by homering to win Game Four in 12 innings. The stage was set for a Seaver-Billingham rematch in the finale.

In the first inning of Game Five, Ed Kranepool drove in two runs with a bases-loaded single. The Reds struck back as Driessen brought in Morgan in the third inning, while Rose crossed home plate to tie the game on a single by Perez in the fifth. Then the Mets blew it open with four runs in the home fifth to chase Billingham, and who better to drive in the go-ahead run than the Say-Hey Kid. Having already said “goodbye to America” at his retirement game, the 42-year-old Willie Mays, batting for Kranepool, collected a bases-loaded single to score Felix Millan. Seaver led off the sixth inning with a double and scored on a Cleon Jones single to give the Mets a 7-2 lead. McGraw relieved Seaver and got the last two outs and then ran for his life as fans stormed the field.

Amid banners that proclaimed “Rose is a Weed” and “This Rose Smells,” the series marked an acrimonious victory over the otherwise superior Reds. Charley Hustle compared the Mets and their fans to a flock of zoo animals, while manager Sparky Anderson expressed his dismay at their riotous celebration: “I can’t believe this could happen in this country, but then I’m not sure New York is part of this country.”26 In spite of geography, and against all probability, the Mets were returning to the World Series for the second time in five years.

To paraphrase Yogi Berra’s rhetoric, the 1973 World Series was indeed “déjà vu all over again” for the Mets. After winning an unexpected division title and then pulling off a stunning upset for the pennant, the underdog Mets faced a proven winner in the World Series: the Oakland A’s. The defending world champion A’s upset the baseball establishment by uniforming their long-haired, bearded players in green and gold haberdashery while experimenting with orange baseballs, designated runners, and ballgirls. Even their manager, Dick Williams, otherwise a traditionalist, sported long hair and a mustache. The Swingin’ A’s boasted a rotation featuring Catfish Hunter, Vida Blue, and Ken Holtzman, with Rollie Fingers in the bullpen, while their lineup was punctuated by Bert Campaneris, Joe Rudi, Sal Bando, Reggie Jackson, and Gene Tenace.

After the teams split their first two games amid more controversy — Oakland owner Charles O. Finley forced infielder Mike Andrews to sign a waiver that he was unfit to play after he bungled two routine grounders in New York’s 12-inning victory in Game Two — Seaver faced Hunter in Game Three. Night games in the World Series were still a novelty and didn’t seem like such a great idea when the temperature hovered near 40 degrees for the three games at Shea. The Mets still started out hot, taking a 2-0 lead before Hunter could gain his composure. Bando doubled in the sixth inning and scored on another double by Tenace. Campaneris led off the eighth inning with a single, stole second, and tied the game on a single by Rudi. Seaver exited after eight innings. McGraw, who threw 10 innings in relief in the first three games, left after the 10th. Harry Parker allowed the go-ahead run the following inning. But the Mets managed to win the next two and jetted back to warm, sunny Oakland a win away from a world championship. Berra could have handed the ball in Game Six to George Stone, who became the favorite among second-guessers, but Yogi went with his best and brought back Seaver to face Hunter again.

Seaver later admitted that he lacked his “good hard stuff” as Oakland scored twice early and held on for the 3-1 win that tied the Series. Remarkably, the A’s had yet to hit a home run in the Series entering Game Seven, but two third-inning blasts by Campy and Reggie sank the Mets and Matlack, 5-2. A decade would pass before the Mets even competed again to play October baseball.

Despite a bittersweet 1973 season, Seaver converted his stellar performance and second Cy Young into a $172,000 contract. At the time, he was the highest-paid pitcher in baseball. However, the pain in Seaver’s shoulder and hip that impeded his performance down the stretch continued to plague him in 1974. Facing Steve Carlton and the Phillies on Opening Day for the second consecutive year, Seaver twice failed to hold leads before Tug McGraw surrendered a winning home run to rising star Mike Schmidt. Seaver’s fastball was even less effective in his second start, prompting pitching coach Rube Walker to ask if he was injured. Only after five starts did Seaver finally register a win; by Memorial Day, he was 2-5. Atlanta’s Johnny Oates called his fastball “a lame duck.”27 Meanwhile, Seaver was being described as surly in the clubhouse and in dealings with the media. In his column in the New York Daily News, Dick Young wrote that Seaver was an agent of discontent among his teammates. In a summer of headlines dominated by Watergate, this curmudgeonly Dick made it perfectly clear that Seaver had made his enemies’ list; it would not be the final war of words between the two.28

For the first time in his star-studded career, Seaver had an ERA above 3.00 and failed to make the All-Star team. But 1974 was not a complete washout. Through September, he managed to strike out 187 batters while pitching through pain. Late in the month, he attended two osteopathic sessions with Dr. Kenneth Riland. The doctor diagnosed him with a sciatic nerve problem and a dislocated pelvic structure, both legacies from years of hard throwing. Seaver later estimated that Riland worked on him for less than 10 minutes. After previously announcing that his season was over, he requested one final start. Facing Philadelphia in the next to last game of the 1974 campaign, Seaver still had a remote chance of becoming the first National League pitcher to strike out 200 batters in seven consecutive seasons. Despite an early two-run double by Willie Montanez that proved to be the deciding hit in an inevitable 2-1 loss, Seaver was masterful. He fanned eight Phillies through six innings and struck out the side in the seventh. The Phillies put the ball in play in the eighth and he entered the final inning still two strikeouts shy of the elusive 200 mark. After punching out Mike Schmidt with fastballs to lead off the ninth inning, Seaver fanned Montanez to achieve 200 strikeouts in seven seasons. The Mets had the cover image ready for their 1975 yearbook, a photo of Seaver posed with baseballs forming the number 7. Then, for good measure, Seaver ended his season by striking out Mike Anderson. The Mets went down meekly to ensure his first nonwinning season at 11-11.

With a rejuvenated arm and a new pelvic structure, the Seaver of old re-emerged at Shea in 1975. The pinnacle of his season occurred on September 1 when he reached two statistical milestones in midst of a shutout against Pittsburgh. When Seaver struck out Manny Sanguillen in the seventh inning, he reached a plateau that even Walter Johnson and Rube Waddell never attained. He became the first pitcher to strike out 200 batters in eight consecutive seasons. Earlier in the season, Dan Driessen became his 2,000th career strikeout victim. The victory for interim manager Roy McMillan – Yogi had been fired in August — would be Seaver’s 20th of the season, and he added add two more to finish at 22-9 and earn his third Cy Young Award. He was denied another victory despite taking a no-hitter two outs into the ninth inning at Wrigley Field on September 24. Joe Wallis singled to break up the bid, but even if he’d gotten Wallis, it wouldn’t have been a no-hitter because the Mets did not score. Seaver left after 10 shutout innings and the Mets lost on a bases-loaded walk in the 11th inning, 1-0.

Seaver edged out San Diego’s Randy Jones to earn his third Cy Young, becoming the second pitcher, after Sandy Koufax, to win the award three times. Contract negotiations, on the other hand, would prove to be a whole different ballgame.

Seaver edged out San Diego’s Randy Jones to earn his third Cy Young, becoming the second pitcher, after Sandy Koufax, to win the award three times. Contract negotiations, on the other hand, would prove to be a whole different ballgame.

Two National League pitchers, Los Angeles’ Andy Messersmith and Montreal’s Dave McNally, had played the entire 1975 season without contracts. On December 23 arbitrator Peter Seitz ruled that both players were free to negotiate new contracts to the highest bidding team on the open market. The reserve clause, which had bound a player to his employer for life, was obsolete, and the replacing system that granted free agency to players with six years’ experience was met with vociferous opposition by the baseball establishment. As the Mets’ union representative, Seaver worked to create an equitable negotiating environment for his fellow players. Now he wanted to experience the rewards.

Seaver demanded a three-year, $825,000 contract. Team president M. Donald Grant grew incensed and threatened to trade him to the Dodgers for Don Sutton. One pitch into the 1976 season, Seaver would become a “10-for-5 man.” In another coup for the players in a previous round of labor negotiations, any player with 10 years’ experience, five with the same team, could reject any prospective trade, leaving the Mets only a few months to arrange a deal for Sutton. Rather than risk a public-relations nightmare from trading their franchise player, the Mets agreed to renegotiate with Seaver, offering an incentive-based contract with a base annual salary of $225,000 through 1978. Though Seaver reluctantly agreed, it cost him any professional rapport he had with Grant.

Though Seaver’s record in 1976 was a disappointing 14-11, his offensive support produced only 15 runs in his aggregate losses. Registering seven consecutive fruitless starts (0-4 with three no-decisions) between July 13 and August 24, he still managed to limit the opposition to a 2.13 ERA. Seaver’s ERA for the year was 2.59 (third in the league), and his 235 strikeouts earned him his fifth NL strikeout crown. He also extended his record to 200 whiffs in nine consecutive seasons. As impressive as Seaver’s 1976 numbers might have been, they represented his last hurrah in a Mets uniform.

The Mets reacted to baseball’s new economic reality by failing to initiate any intention to sign any of the 24 potential free agents. After they had finished a pedestrian third place in each of the previous two seasons, the environment was ideal for the Mets to improve their offense by signing a free agent. In sportswriter Bill Madden’s eyes, Gary Matthews would have been “a perfect fit” to play center field. Yet, as Seaver decried to a barrage of reporters in spring training, he was dismayed by his club’s refusal to adapt to changing economic times.29 The contract squabble of the year before still fresh in his mind, Seaver watched as other teams signed players of star caliber. Across town in the Bronx, the six-year, $2 million contract the Yankees gave Don Gullett to sign him away from Cincinnati suddenly rendered Seaver’s contract outmoded. Observant of the ordeal teammate Dave Kingman endured in his own negotiations, Seaver wondered if he would have been better off not signing a 1976 contract and filing for free agency. Grant’s reaction was predictable, deprecating Seaver as “an ingrate” and blasting the economic system his union had brought forth.30

“We will try to run our business in a sensible way,” Grant said. “Nobody is going to plan to spend a lot of money for players and lose money at the park.”31 He understood the economics of the game, that free-agent contracts would inflate ticket prices, thereby pricing his product out of the reach of thousands of Mets fans. An acrimonious relationship between Seaver and Grant became even more pronounced. Most of the New York writers sided with Tom Terrific, including Maury Allen of the New York Post.

“When you have the best pitcher in the world, you sign him,” Allen wrote. “You don’t humiliate him. Grant can’t stand opposition from Seaver or anybody.” In assessing Grant’s stance on contract negotiations, Allen charged that “he’d sooner lose a pennant” than accede to the demands of his players and their agents.32

There was one notable holdout in the press. On the Seaver front, Grant soon formed an axis with one of the city’s most powerful voices, Dick Young of the Daily News. A maverick Republican in a city of Democrats, Young reacted to Seaver’s free agency regret by labeling him “a troublemaker,” insistent that no team would be interested in signing him.33 The sports section at the Daily News was rendered into “the battle page,” as Young and the pro-Seaver Jack Lang sparred using pens rather than foils. Seaver appeared unfazed by the diversions off the field, posting a record of 4-0 by the end of April and tossing his fifth one-hitter as a Met, against the Cubs. Seaver’s performance did not prevent Young, however, from continuing his offensive:

“Tom Tewwific,” he wrote, “[is] a pouting, griping, morale-breaking clubhouse lawyer poisoning the team.”34 Young was correct about the Mets’ position in the standings. By the end of May, the team was already 13 games out of first place. The Mets had hired their fourth manager in two years, replacing Joe Frazier with the untested Joe Torre. Meanwhile, the trading deadline was only two weeks away.

Rumors began to circulate that general manager Joe McDonald was arranging a deal with Bob Howsam, his counterpart in Cincinnati, to send Seaver to the Reds. On June 7 Seaver struck out 13 Reds in an 8-0 shutout at Shea to improve his record to 6-3. Sparky Anderson remembered the game: “For years, I had been naming Tom, whenever I was asked, as baseball’s best pitcher. I never saw him better than he was [that night] when he whipped us. It was an artistic effort. I drooled when I thought of what a pitcher of Seaver’s class could do for us.”35

After Seaver won in Houston on June 12, the Mets offered to extend his contract so that it would be comparable to a free-agent offering elsewhere. He would receive a three-year extension which included a pay raise to $300,000 in 1979 and then to $400,000 in 1980 and 1981. On June 14, one day before the trading deadline, Seaver contacted McDonald to halt trade negotiations with the Reds. He planned to remain a Met.

Conventional wisdom suggests that if something sounds too good to be true, it often is. After he agreed in principle to a three-year contract extension with the Mets, the ordeal appeared over for Seaver. However, as he read the Daily News on the road in Atlanta, he became appalled by the latest offensive launched from Dick Young’s typewriter:

“Nolan Ryan is getting more now than Seaver, and that galls Tom because Nancy Seaver and Ruth Ryan are very friendly and Tom Seaver long has treated Nolan Ryan like a little brother.”36 As Seaver told Bruce Markusen years later, his welcome mat with M. Donald Grant had finally run out. Incensed that Young would pull a false punch aimed at his family, Seaver bolted in search of public-relations director Arthur Richman. “Get me out of here!” he ordered Richman, “and tell Joe McDonald everything I said last night is forgotten.”37

McDonald had no leverage to pull the trigger on a deal he regretted making. On June 15 Tom Seaver was traded to the Cincinnati Reds for a package of players, none older than 26: pitcher Pat Zachry, infielder Doug Flynn, and outfielders Steve Henderson and Dan Norman. Not only would New Yorkers endure the turbulence of the .44-caliber killer, a crippling blackout followed by massive looting and rioting, and a bitter four-candidate campaign for mayor of a near-bankrupt city — for Mets fans, the summer of 1977 would also live in infamy for a trade known as the Midnight Massacre.

After an emotional press conference in the Shea Stadium clubhouse, Seaver was ready to move on, joining his new teammates in Montreal. Disappointed by the situation he was leaving in New York, at least he would no longer have Johnny Bench, Pete Rose, or Joe Morgan to face. Though victorious in the previous two World Series, the Reds trailed Los Angeles in the 1977 National League West standings. Tony Perez was gone, but George Foster emerged as a power source; his 52 home runs were the most by any major-league slugger in a dozen years. Despite a 14-3 mark with a 2.34 ERA for Cincinnati — including a victory over old pal Jerry Koosman at Shea Stadium in August — Seaver did not re-ignite his teammates to overtake the Dodgers in the standings. While he earned his fifth and final 20-win season, he fell short of his 10th straight 200-K season by four strikeouts.

He brought out scores of fans to Riverfront Stadium on days he pitched, and he also conveyed a presence to the locker room that was felt even among the two-time world champions. “Seaver was a joy to have around. He is such a bright young guy that his weird sense of humor almost seems out of character,” recalled Sparky Anderson on Tom Terrific’s immediate impact. “His personality fit right in with the veterans. They accepted him and he accepted them. Moreover, Tom was of tremendous help to our young pitchers who frequently sought his advice.”38

He brought out scores of fans to Riverfront Stadium on days he pitched, and he also conveyed a presence to the locker room that was felt even among the two-time world champions. “Seaver was a joy to have around. He is such a bright young guy that his weird sense of humor almost seems out of character,” recalled Sparky Anderson on Tom Terrific’s immediate impact. “His personality fit right in with the veterans. They accepted him and he accepted them. Moreover, Tom was of tremendous help to our young pitchers who frequently sought his advice.”38

Seaver, who hadn’t really bonded with a manager since the death of Gil Hodges, worked well with one of the game’s top dugout minds. “Sparky communicates well. He’s intelligent. He has the ‘smarts.’ He believes in his convictions. He’ll argue to the death when he thinks he’s right. And he often is right.”39 Expectations were high for the 1978 Reds to re-establish themselves as the pre-eminent club in their division. Seaver did his part, posting a record of 16-14 with 226 strikeouts and a 2.88 ERA. On June 16 he reached an achievement never accomplished as a Met: He pitched a no-hitter, against the St. Louis Cardinals. The Reds, however, fell short in the standings to the Dodgers and with Dick Wagner now operating as Reds’ general manager, he wanted his own man in the dugout. Anderson was let go.

Although injuries impeded Seaver’s performance early in the 1979 season, he recovered to win 14 of his last 15 games. After two bridesmaid finishes, the Reds won their division once again under new manager John McNamara. The Pittsburgh Pirates, clad in their stovepipe hats emblazoned with stars from Willie “Pops” Stargell, emerged victorious from a white-knuckle divisional race with the Expos. It would be the fourth League Championship Series of the decade between Pittsburgh and Cincinnati, with the first three won by the Reds. This time, however, Cincinnati was without Rose, who’d signed as a free agent with Philadelphia the year before. Though Seaver limited the Pirates to two runs and five hits in Game One, Pittsburgh starter John Candelaria was equally effective. Tom Terrific had long since exited the game when Stargell snapped the tie in dramatic fashion, hitting a three-run homer off reliever Tom Hume in the top of the 11th inning. The Pirates went on to sweep the Reds before defeating the Baltimore Orioles in the 1979 World Series.

Seaver’s 10-8 season in 1980 was marred by disappointment. The Reds finished third and he suffered from arm trouble for the first time in his career. The following season was equally disappointing, but for vastly different reasons.

Although the Reds posted the best record in baseball, a midseason players strike resulted in a unique split-season format. As the Reds finished second in both halves, they had little recourse in the postseason besides watching the Dodgers’ divisional playoff against the Astros on television. Moreover, Seaver’s record of 14-2 represented the highest winning percentage in either league. Unfortunately, his comeback season coincided with Fernandomania, the pandemonium that surrounded the Dodgers’ unhittable rookie phenom Fernando Valenzuela. Seaver lost the Cy Young Award to Valenzuela by one vote. The 1981 season was not without personal acclaim for Seaver. He reached the 3,000-strikeout plateau when he fanned Cardinal Keith Hernandez on April 8.

As the decade of the 1980s progressed, so did the frustration for Seaver. Defections continued as Ken Griffey and George Foster were traded, while Dave Collins was lost to free agency. Consequently, the Reds plunged to the division cellar in 1982, recording an abysmal record of 61-101. Not even Seaver was immune; he went just 5-13 with an unsightly ERA of 5.50. Emerging from the worst record in franchise history, the Reds were eager to part with their 38-year-old pitcher with the suspect shoulder. At least one team was equally enthusiastic in trading for Seaver.

In 1980 the New York Mets had been sold to a consortium led by publisher Nelson Doubleday and developer Fred Wilpon. Rebranding the Mets as “the People’s Team,” Doubleday and Wilpon vowed to field a winning team at Shea Stadium, and allowed general manager Frank Cashen the pursestrings to field a contender. The resurrection of the Mets was a struggle at first. Not even George Foster, brought to the Mets with great fanfare, and new manager George Bamberger could lift the Mets in 1982. Cashen turned his sights to a third George, trading pitcher Charlie Puleo and two minor-league players to reacquire Seaver from the Reds on December 16. As M. Donald Grant had retired and Dick Young was reduced to journalistic obscurity, the coast was clear for Seaver’s return to New York.

Over 48,000 fans flocked to Shea Stadium for Mets nostalgia on April 5, watching Tom Terrific throw six shutout innings against the Phillies in his return. Rookie Doug Sisk, who got the win in relief against Steve Carlton, observed that he “didn’t know [Seaver] could still throw that hard.”40 It was his 14th Opening Day assignment, tying another Walter Johnson pitching record. Seaver was the most durable pitcher on the 1983 Mets, tying Mike Torrez with 34 starts and leading the staff with 135 strikeouts in 231 innings. However, not even Seaver, rookie Darryl Strawberry, or midseason acquisition Keith Hernandez could save the Mets. Seaver went 9-14 in New York’s seventh consecutive losing season. Though that long streak was about to end, Seaver would not experience it.

The resolution of the 1981 players strike established an annual pool of players from which teams could select players as compensation for free-agent losses. With several young prospects they were anxious to keep, the Mets did not envision that any team would want Seaver, now 39, whose value was higher in New York because of his appeal as an attendance draw. The 68-94 Mets kept their young players but lost their Franchise. Again.

The Chicago White Sox lost pitcher Dennis Lamp to the Toronto Blue Jays as a free agent and were eligible to take an unprotected player from any other club as compensation. On January 20, 1984, they selected Seaver. On the heels of winning 99 games before losing the American League Championship Series to the Orioles, the White Sox were excited to bring in a pitcher of Seaver’s craft and experience.

“Tom’s a competitor. I think he’s going to be happy here,” said White Sox president Eddie Einhorn. “This is the best place for him for the rest of his career. It’s an excellent way to end it. It’s possible he’ll get back into the World Series. He’ll certainly reach 300 wins with us. And the atmosphere is great.”41

Einhorn’s predictions were not entirely wrong. Seaver did achieve his 300th win with the White Sox, on August 4, 1985, crashing Phil Rizzuto Day at Yankee Stadium to defeat the Bronx Bombers at home. (Tom Terrific joined the Scooter in the Yankees’ broadcast booth after retiring as a player.) Though he ended his career with a World Series entrant, it would not be in a Chicago White Sox uniform.

The White Sox had capitalized on weak American League West opponents in 1983, winning the division by 20 games over second-place Kansas City. However, their style of “winning ugly” proved to be a one-year wonder. Though he won a respectable 15 games in 1984 and 16 in 1985, the White Sox had returned to mediocrity. Seaver did enter the record books by being the pitcher of record on May 9, 1984. When Harold Baines won the game with a home run in the 25th inning, Seaver won the first eight-hour game in major-league history. It had been stopped after 17 innings and resumed the next afternoon. As the scheduled starter later that day, he became the first White Sox pitcher since Wilbur Wood to win two games played in the same day. In 1968 Seaver had started and thrown 10 shutout innings in what turned into a 24-inning game at the Astrodome. Now he entered a game after 24 innings and picked up the win in his first relief appearance since 1976.

As the 1986 season approached, Seaver could see the terminus of his professional baseball career. After his mother died that spring, he wanted to spend more time with his family, which now included two young daughters. Seaver asked to be traded to a New York team or to Boston to be closer to his Connecticut home. On June 29 the White Sox granted him his wish, dealing him to the Red Sox for utilityman Steve Lyons. A change of Sox reunited Seaver with manager John McNamara in Boston. Led by perennial batting champion Wade Boggs, dependable outfielders Jim Rice and Dwight Evans, and pitching sensation Roger Clemens, these Sox were poised for their first World Series appearance since 1975. After a tight pennant race with the Yankees and an exciting Championship Series victory over the Angels, the Red Sox did indeed return to the October classic. As for Seaver, after posting a 7-13 record in an injury-plagued season, he was left off the postseason roster. He was unavailable in Game Six when Johnny Mac required a right-hander in the 10th inning, a frame that ended when a groundball passed between Bill Buckner’s weathered ankles. The Red Sox went on to lose Game Seven and the World Series. The winners? The New York Mets.

Seaver did try to put on uniform number 41 for the Mets one last time. His attempted comeback with the 1987 Mets proved fruitless and Seaver announced his retirement on June 22. A year later he joined Casey Stengel and Gil Hodges on the short list of Mets notables to have their numbers retired. Two decades later, he remained the only Met to have his number retired for his achievements as a player. And they were many. Most of his Mets records may never be broken, including wins (198), complete games (171), shutouts (44), starts (395), innings (3,045), strikeouts (2,541), and ERA (2.57).

Besides broadcasting Yankees games for five seasons, Seaver worked as a public-relations representative for the Chase Manhattan Bank. He spent seven years as a Mets broadcaster before leaving after the 2005 season. Inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1992 by an unprecedented margin, Seaver attracted a then-record 10,000 pilgrims to witness his induction speech. Among them, Rudy Gafur, who chronicled the milestone in his baseball diary entitled “Cooperstown Is My Mecca”:

“Seaver finished his career with 311 wins and 205 losses. Among his numerous awards and honors are Rookie of the Year, National League Pitcher of the Year, and Cy Young Award. He also shares or holds many National League records such as the lowest earned run average (2.73) for a pitcher with 200 or more wins and most consecutive seasons with 200 or more strikeouts. In a speech filled with emotion, Tom Terrific spoke of his deep love and respect for the game which meant so much to him. He thanked his family and friends for support.”42

After living most of his adult life in Connecticut, Seaver later returned to his native California, establishing a winery with his wife, Nancy, near Calistoga. Seaver always has been a man of his times. Born into a middle-class family and raised during America’s period of postwar prosperity, Seaver represented a new breed of player: independent, cerebral, educated. As the New York Mets’ “franchise player,” he was the spokesman for thousands of suburbanites, blue-collar workers, and immigrants united by their team’s emergence as World Series champions in 1969. A man of profound opinions, he preferred not to disclose his personal stance on controversial issues away from baseball. Though he worked tirelessly on behalf of the Major League Baseball Players’ Association, he never filed for free agency.

Records, of course, are made to be broken and since the original publication of this biography, two of the standards cited in the introduction have since been surpassed. “Move Over Henry, Here Comes Barry” was the song they were singing in San Francisco as Barry Bonds topped Hank Aaron’s home run standard in 2007 before extending the record to 762. Meanwhile, Hall of Famer Ken Griffey Jr. was elected in 2016 with 99.1% of the ballot, a record since surpassed by Mariano Rivera’s unanimous election in 2019. Decades from now, fans will continue to visit Seaver’s Cooperstown plaque, which has since been joined by a second Met, Mike Piazza, in 2016.

The 2019 season marked the 50th anniversary of Neil Armstrong’s small step for man and Tom Seaver’s giant leap for Metkind. Sadly, the semicentennial celebrations at Citi Field shall persist without the Mets’ franchise player. In March 2019, Seaver announced that he was retiring from the public eye as he was diagnosed with dementia. The Mets also announced that the address for Citi Field, 123-01 Roosevelt Avenue, shall be changed to 41 Tom Seaver Way. Included among the 50th anniversary celebrations was the unveiling of a statue of Tom Seaver, a player forever synonymous with the New York Mets and the Miracle at Flushing Meadows.

On September 2, 2020, baseball fans were shocked and saddened to learn that the noblest Met of them all had passed away two days before. Nancy, Sarah, and Anne Seaver lost their husband and father on August 31. He died in Calistoga, California at the age of 75. Tom had been battling Lyme disease for the better part of three decades. Ultimately, he died of complications of Lewy body dementia and COVID-19.

Sadly, parallels may be drawn between Tom Seaver and Christy Mathewson, both in life and in death. Just as Matty brought a human face to soldiers in the First World War who died of tuberculosis, Seaver became identified as an athletic hero associated with COVID-19 during a global pandemic.

What followed may have been the largest outpouring of grief among baseball fans since Mickey Mantle passed away a quarter-century earlier. To borrow a line from a popular Broadway musical, Seaver was a Met and a Met all the way. Even after he was sent to the Reds in an unpopular trade, Topps chose a photograph at Shea Stadium for his first card in a Cincinnati uniform.

Winner of 311 games, he was never afraid to dirty his right knee if it meant helping his team. Immortalized as “The Franchise” in Flushing and on a bronze plaque in Cooperstown, Tom Seaver may best be remembered as the ace of a Mets team that surprised everyone but themselves by winning an improbable World Series against the Baltimore Orioles. A great miracle happened there.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted baseball-reference.com, IMDB.com, retrosheet.org, and the following:

Appel, Martin. Yesterday’s Heroes: Revisiting the Old-Time Baseball Stars (New York: Wm. Morrow & Co., 1988).

Aron, Eric. “Dick Williams,” in The 1967 Impossible Dream Red Sox: Pandemonium on the Field, Bill Nowlin and Dan Desrochers, eds. (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2007).

Lyons, Douglas B. The Baseball Geek’s Bible: All The Facts and Stats You’ll Ever Need (London: MQ Publications Ltd., 2006).

Manuel, John. “Coaching Legend Dedeaux Dies at 91,” on Baseball America (January 6, 2006): 13 pars. [Journal Online]. Available from baseballamerica.com/today/news/060106dedeaux.html. Accessed February 2, 2008.

Miller, Marvin. A Whole Different Ballgame: The Sport and Business of Baseball (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1991).

Ranier, Bill, and David Finoli. The 1979 World Champion Pittsburgh Pirates: When the Bucs Won It All (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2005).

Weissman, Harold, ed. New York Mets Official 1975 Yearbook (Flushing, New York: The New York Mets, 1975).

Notes

1 Gene Schoor. Seaver (Chicago: Contemporary Books Inc., 1986), 32.

2 Schoor, 58.

3 Schoor, 58.

4 Earl Weaver and Berry Stainback. It’s What You Learn After You Know It All That Counts: The Autobiography of Earl Weaver (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co. Inc., 1982), 171.

5 Duncan Bock and John Jordan. The Complete Year-By-Year N.Y. Mets Fan’s Almanac (New York: Crown Publishers Inc., 1992), 50.

6 Bock and Jordan, 110.

7 Jack Lang and Peter Simon. The New York Mets: Twenty-Five Years of Baseball Magic (New York: Henry Holt and Company, Inc., 1986). 133.

8 Maury Allen. After the Miracle: The Amazin’ Mets — Two Decades Later (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989), 233.

9 Bruce Markusen. Tales from the Mets Dugout (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2005), 22.

10 Ralph Kiner and Danny Peary. Baseball Forever (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2004), 198.

11 Kiner and Peary, 198.

12 Allen, 236.

13 Allen, 235.

14 Schoor, 125.

15 Allen, 237.

16 Allen, 237.

17 Weaver and Stainback, 171.

18 Bock and Jordan, 75.

19 Schoor, 162.

20 imdb.com.

21 Bock and Jordan, 94.

22 Tim Hamilton, ed. “That Championship Season 1973,” in Now The Fun Starts! The New York Mets Official 1983 Yearbook (Flushing, New York: Doubleday Sports Inc., 1983), 6S.

23 Bock and Jordan, 106.

24 Schoor, 194.

25 Schoor, 195.

26 Bock and Jordan, 111.

27 Bock and Jordan, 120.

28 Bock and Jordan, 117.

29 Bill Madden. “The True Story of the Midnight Massacre: How Tom Seaver Was Run Out of Town 30 Years ago.” New York Daily News, June 17, 2007: par 9; [journal online]; Available from dailynews.com; accessed October 5, 2007.

30 Schoor, 235.

31 Bock and Jordan, 138.

32 Schoor, 238.

33 Schoor, 238.

34 Schoor, 238.

35 Sparky Anderson and Si Burick. The Main Spark: Sparky Anderson and the Cincinnati Reds (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, 1978), 224.

36 Madden, par. 24.

37 Madden; Markusen, 88.

38 Anderson, 226.

39 Anderson, 281.

40 Bock and Jordan, 175.

41 Paul Jensen and Ken Valdiserri, eds. Chicago White Sox 1984 Yearbook (Chicago: White Sox Public Relations Department, 1984).

42 Rudy A.S. Gafur. Cooperstown Is My Mecca (Toronto: Rudy A.S. Gafur, 1995), 100-101.

Full Name

George Thomas Seaver

Born

November 17, 1944 at Fresno, CA (USA)

Died

August 31, 2020 at Calistoga, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.