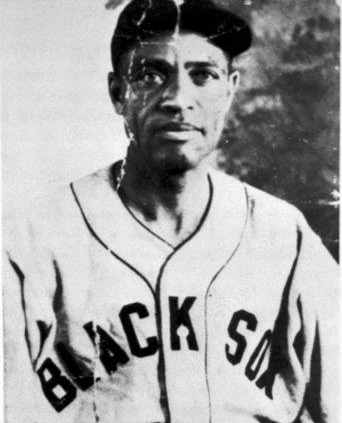

Crush Holloway

“He was what could be classified as a crazy ball player. You could never defense him well or pitch him certain kinds of pitches because he was so unpredictable. If you were nine runs down, Holloway might try to steal home if he thought it might help to motivate the team in their comeback effort.” –Clint Thomas1

“He was what could be classified as a crazy ball player. You could never defense him well or pitch him certain kinds of pitches because he was so unpredictable. If you were nine runs down, Holloway might try to steal home if he thought it might help to motivate the team in their comeback effort.” –Clint Thomas1

Crush Holloway was an all-around ballplayer, often hitting leadoff for some of the most storied teams in Negro League history where he had a knack for getting on base and wreaking havoc on the base paths, doing anything needed to guide his team to victory. Holloway learned his aggressive baserunning style by emulating his idol, Ty Cobb. Holloway explained this unlikely connection. “His picture used to come in Bull Durham tobacco. Showed the way he’d slide. That was my hero. I said, ‘I want to slide like Ty Cobb. I want to run the bases like him.’”2 Holloway also played for a lot of teams and had a penchant for jumping from one to another. So much so that while playing for manager and future Hall of Famer Pete Hill in Baltimore, Holloway was nicknamed “The Frog” due to his constant hopping from team to team.3

Crush Christopher Columbus Holloway, when talking about his early life and unique moniker, told this to baseball historian John Holway in 1969:

Crush, that’s my real name, that ain’t no nickname. And I’ll tell you how I got it. The day I was born, September 16, 1896, down in Hillsboro, Texas, my father was fixing to go see a “crash,” a collision.4 They’d take two old locomotive engines and crash them together for excitement, sort of a fair, and my father was going to see it. Before he got on the train, somebody pulled him off and said, “Your wife is about to have a child.” And when I turned out to be a boy, he named me “Crush.” That’s how I got my name. Oh, I’ve got some middle names, Crush Christopher Columbus Holloway, but I don’t use those other names. I just use Crush, ’cause I like Crush better.5

Holloway’s father, Thomas Holloway, was born on August 10, 1866, in South Carolina and his mother, Dora Criner, was born October 1, 1869, in Texas.6 The couple had eight children and life couldn’t have been easy on the family farm, where Thomas and his oldest son, Crush, toiled endlessly in the fields producing cotton, corn, and wheat. The Holloway family owned the farm and Thomas was also a schoolteacher, although his son didn’t make it past the fourth grade.7 Holloway explained how difficult his early life was:

I was the oldest boy, see. Had five sisters, but they couldn’t do nothing on the farm. I was the only boy he could depend on, you know what I mean? I had brothers, but they were so young, ten to twelve years younger than me. They couldn’t do anything. That’s why Pop would depend on me. I was his man, had to do everything. That’s what I did until I got grown.8

Four of Holloway’s sisters, Verna (1898), Zelma (1902), Ruth (1909), and Tommie (1916), were all younger than him; only Olga (1894) was older. Holloway also had two much younger brothers, Richard (1904) and Tyree (1905).

Holloway so badly wanted to escape the labor of the family farm that he attempted to enlist in the US Army during World War I, but quotas kept him out until his chances faded with the ending of the conflict. Finally, at the age of 21, Holloway left with his father’s blessing to pursue a career in baseball. Holloway recalled his parting conversation with his father like this: “My father said, ‘You’re a grown man, you can do what you want to do, but I want you to stay here with me.’ I said, ‘No! I’m going to play baseball. That’s the end of it, Pop. I got to go.’ He was a good father, didn’t try to hold me. He knew I did my chores right. So he let me go.”9

As a kid Holloway snuck off on Sundays to play sandlot ball with his friends until the sun went down. Back on the farm, he hit pebbles with a broomstick and imagined he was his favorite hitter, Frank “Home Run” Baker, smashing homers into the distance.10 Holloway’s dream became a reality in 1919 when he suited up for his first professional team, the Waco Black Navigators. The team struggled mightily for the first three months of the season until it was sold to a man named L.W. Moore and moved to San Antonio to become the formidable Black Aces.11

The 1919 San Antonio Black Aces were a loaded squad with talent that included such Negro League stalwarts as Hall of Famer Biz Mackey, Steel Arm Davis, Robert “Highpockets” Hudspeth, Johnny Jones, and Namon Washington. The San Antonio Evening News compared second baseman Holloway to Eddie Collins and praised him in a September 19, 1919, column, writing, “He covers about as much ground as a big top at the circus, and they never come down there too hot for him.”12 Black and White fans alike rallied around the team, causing the San Antonio Evening News to also exclaim, “The Black Aces would give any Negro club in the country a battle.”13

By season’s end it was determined that the San Antonio Black Aces would face off against the Dallas Black Marines to determine the Texas Negro League champion and collect a cash prize of $1,000. The Black Aces sported a record of 45-10 and the Black Marines were right on their tails at 51-17.14 This ferociously fought series came down to a deciding fifth game when the hometown Black Aces quickly fell into a five-run deficit. Clawing back, the Aces managed to tie it up, 5-5, going into the ninth inning when Steel Arm Davis smashed a double to drive in the winning run.15 The win soon turned bittersweet, though, as 1919 turned out to be the only season of existence for the champion San Antonio Black Aces.

C.I. Taylor, owner of the Indianapolis ABCs, knew talent when he saw it and he quickly pounced and offered contracts to six of the Black Aces’ best players. Holloway, Henry Blackmon, Highpockets Hudspeth, Biz Mackey, Morris Williams, and Namon Washington were all set to join the ABCs in the inaugural season of the newly formed Negro National League, but Holloway balked.16 Holloway described to Holway the dismantling of his beloved Black Aces and why he refused to join his teammates in Indianapolis: “It broke our club all to pieces. I didn’t go that year. I didn’t want to go ‘cause I was mad. I was so mad I didn’t know what to do.” Holloway cooled down enough to join the ABCs the following season, in 1921, and later called the 1922 ABCs the greatest team he ever played on.17

The Indianapolis News welcomed Holloway to the team with this glowing mention: “Crush Holloway, who will take care of the keystone sack, hails from Texas. He is a big fellow, handles himself with ease around second and gets the ball away in good form. A reputation as a hitter precedes him and some of the players who have seen him slam the ball are loud in their praises of him. He bats from the left side of the plate, and hits them far and often.”18

Holloway was one of many great Black ballplayers from the Lone Star state that included Cyclone Joe Williams, Willie Wells, Hilton Smith, Rube and Bill Foster, Jesse Hubbard, and fellow Black Ace and ABC teammate Biz Mackey. He was especially fond of Mackey, of whom he said, “And he was funny. He was jolly, especially with those fast men who said they were gonna steal on him. When he’d throw them out, he’d get such a kick out of it, he’d fall down laughing.”19

Holloway was never shy about heaping praise on his fellow teammates and the man standing to his right in the ABCs outfield was no exception. Holloway considered Oscar Charleston to be the greatest defensive outfielder he’d ever witnessed and said that if Charleston “had time to get under a fly ball, he’d walk, he had it timed, he’d walk fast. And he’d do acrobatics. People used to come out and see him do his stunts in the outfield.”20 Holloway also credited ABCs owner and manager C.I. Taylor with helping him convert to the outfield and refining his base-running skills.21

While Holloway was a consistent .300 hitter and above-average right fielder in his three years with the ABCs, the team never quite reached its potential, playing second fiddle to the powerhouse Chicago American Giants and Kansas City Monarchs.

The California Winter League was a Southern California league that presented the perfect destination for the best Black baseball stars to showcase their talents. Beginning with Rube Foster’s 1910 Leland Giants until the integration of White major-league baseball, Black superstars like Cyclone Joe Williams, Bullet Rogan, Cool Papa Bell, Pop Lloyd, and Satchel Paige were fixtures in the circuit.22 These players dominated their White counterparts, winning more than 60 percent of their matchups, including an incredible 13 of 16 championships between 1924 and 1939. 23

Holloway’s first appearance in the CWL took place in 1922-23 with the St. Louis All-Stars, but he shined most brightly with the CWL champion Philadelphia Royal Giants in 1925-26. Featuring a stacked lineup consisting of old friend Biz Mackey, Rap Dixon, Bullet Rogan, and Newt Allen, Holloway and his band easily outdistanced the White King Soapsters to capture the title.24 Holloway led his team with a .371 batting average, swiped 10 bases, and led the league with 59 hits in 41 games. Overall, in six winter seasons played on the West Coast, Holloway batted .303 in 476 at-bats.25

After the 1923 season the Indianapolis ABCs were raided of some of their best players, including Oscar Charleston and Holloway. Holloway signed with the team he would be most associated with, the Baltimore Black Sox, citing money as his motivation for moving east. Holloway was making $150 a month with the ABCs and $350 to $375 with the Black Sox. Of his jump to the Black Sox, he said: “Man, you know we were going to come here.”26 Holloway had a stellar first season with the Black Sox, hitting .324 with 18 stolen bases, and he credited manager Pete Hill for his improvement at the plate. “He’s the man taught me how to hit to left field,” Holloway explained. “I was pulling the ball. Ball on the outside, I was pulling to right. He gave me a bigger bat [and said,} ‘Now knock that third baseman down. Just step up in front of the plate, hit the ball out in front, see?’ “Oh he was a great hitter.”27

Baltimore’s march toward the pennant ended abruptly with the sudden passing of third baseman Henry Blackmon. This, coupled with an unbalanced schedule in which Hilldale lost and played more games than the Black Sox, allowed Hilldale to capture the flag and earn a spot in the first-ever Negro League World Series against the Kansas City Monarchs, denying the Black Sox their chance at immortality.28

When not taking advantage of the warm California sunshine, Holloway was found tearing around the bases and outfields of the Cuban Winter League. The 1924-25 winter season was Holloway’s first venture to the island and he was in good hands with the Habana team and legendary Cuban Hall of Fame manager Miguel González. There wasn’t a shortage of star power on the Habana team: Holloway shared the field with Cristóbal Torriente, Martín Dihigo, and Rats Henderson, but the team finished a distant second place to the Almendares team despite Holloway’s .311 average. Holloway returned to Cuba just once more, in 1928-29, and seemed to prefer spending his winters playing ball in California.29

For the next four seasons, 1925 to 1928, Holloway patrolled the outfield for the perennial bridesmaids the Baltimore Black Sox. The team was never able to fire on all cylinders during Holloway’s tenure, but it featured a powerful lineup that included a group referred to as the “Four Horsemen,” a quartet that consisted of Jud Wilson, John Beckwith, Heavy Johnson, and Holloway.30 Holloway also was often singled out for his spectacular displays of fielding and in 1926 he was regarded as the second best Eastern League fielder after Oscar Charleston and lauded as a “Ball Hawk” by the Baltimore Afro-American.31 His personal highlights with the Black Sox were many, but a few stood out. In a late July 1927 doubleheader sweep of the Brooklyn Royal Giants, which saw the Black Sox score 20 runs and collect 28 hits, Holloway smashed four safeties, scored four runs, and stole home against fireballer Dick “Cannonball” Redding.32 In another doubleheader sweep, this time of the Bacharach Giants on May 10, 1928, Holloway lit up the scoresheet with four hits, including a double, triple, home run and a stolen base.33

Holloway was a phenomenal basestealer and certainly ranked among the all-time greats. Intimidation may have played a large role in his success. Cool Papa Bell, perhaps the greatest basestealer of them all, explained: “Some guys even sharpened their spikes with a file. Crush Holloway was one. I suppose he wanted to be like Ty Cobb.”34 In an incident on July 8, 1926, Holloway spiked mild-mannered Judy Johnson so badly that Johnson went after him with a bat.35 On July 25, 1931, Holloway almost caused a riot when he once again took out Johnson, this time almost tearing the third basemen’s pants off. Holloway was ejected from the game for unnecessary roughness as the fans swarmed the field.36

Double Duty Radcliffe described another Holloway run-in: “One guy cut me, gave me five stitches. His name was Crush Holloway. He came sliding home and cut open my leg. Two nights later I pitched against him and threw one behind his head about 100 miles an hour. He said, ‘Ain’t no use doin’ that, Duty. You could’a killed me!’ I said, “Man, look where you cut me!” He said, ‘I’m sorry. I beg my pardon.’ He bought me beer all night.”37 Holloway had a chance to defend himself in his 1969 interview with John Holway: “Stealing? Oh, I was pretty good. That’s what they say anyway. Yeah, I made them jump down there on second base. They were scared of me ’cause I’d say, I’m gonna jump on you. I wouldn’t really jump on them, just try to scare them. I didn’t want to hurt anybody. But I filed my spikes, that’s true. Most fast men used to do that. We didn’t intend to hurt anybody, though, just scare them, that’s all. Naw, I wouldn’t hurt anybody for anything in the world. Unless it’s necessary.”38

In late January of 1929, in a blockbuster deal, Holloway was traded to Ed Bolden’s Hilldale Club, also known as the Daisies, along with second baseman Dick Jackson for Merven “Red” Ryan and Frank Warfield. The Philadelphia Tribune commented, “Crush will fit in as a lead-off man that is gifted with the knack of getting on the sacks and in turn can sock the apple at a lively clip.”39 Pittsburgh Courier columnist W. Rollo Wilson sympathized with the Black Sox for losing Holloway, writing, “By my faith, replacing him with a fly-chaser of equal ability isn’t a job you can leave to the janitor. While there are a few who are the peer of the talented Crush none of them is on the mart for sale or barter.”40

In an unfortunate twist of fate, Holloway’s former team, the Black Sox finally reached their potential in 1929 and ran away with the American Negro League crown, winning both the first and second halves to claim the title without him. Holloway’s new team finished a distant third. despite the presence of four future Hall of Famers – Biz Mackey, Judy Johnson, Martín Dihigo, and Oscar Charleston. One has to wonder if team chemistry was an issue with Holloway and Judy Johnson sharing the same field after their previous heated altercation. For his part, Holloway had a stellar season, hitting .296 and leading the league in stolen bases with 29 as reported by the secretary’s office of the American Negro League.41 Holloway’s Hilldale stint was short and he bolted to the Detroit Stars in 1930 to fill the vacant spot in center field.42 (He briefly returned to Hilldale in 1932 to witness the demise of the once-proud club.)

Holloway spent the entirety of the 1930 season manning the outfield for the second-half champions of the Negro National League, the Detroit Stars, but despite playing alongside the great Turkey Stearnes, the Stars faded losing an exciting seven-game series to Cool Papa Bell and his St. Louis Stars. Holloway played all seven games, scored eight runs, struck nine hits for a .310 average and had a sparkling .412 on-base average. Instead of reloading for another shot with Detroit, Holloway jumped back to an old favorite, the Baltimore Black Sox, for the 1931 season. Without him, the Stars suffered through a miserable final season, which turned out to be the last of their existence.

Holloway was 34 years old but showing no signs of slowing down. After a mid-July doubleheader against the Homestead Grays, the Afro-American commented that Holloway’s “fielding in both games was little short of sensational.”43 Charley Walker, president of the Grays, heaped more praise on Holloway, stating, “Crush Holloway is one of the most powerful men on the offense in the game because of his hitting, base running and ability to get on.”44

Holloway’s services were never in more demand than in 1932, when he would display his penchant for hopping from team to team. He began the year with the Black Sox, but on May 24 he was released to the Hilldale Club to play left field.45 His time with Hilldale was short and by early July he was suiting up for the New York Black Yankees. At this time “jumping” in search of a bigger paycheck was becoming a huge problem for Negro League baseball; even the mighty Homestead Grays had a difficult time fielding a team when five of their players bolted.46 Holloway was on the field and batting third in a July 16 matchup with Satchel Paige and his Pittsburgh Crawfords. Paige no-hit the Black Yankees that day, winning 6-0 at Greenlee Field in the Steel City.47

Holloway was still with the Black Yankees in early March of 1933 when they took three of four games against a Cuban team in Puerto Rico as a spring-training warm-up.48 Holloway sprained his ankle and missed some playing time.49 He next turned up in 1933 back in Baltimore, but this time for the Baltimore Sox. The team lost the right to use the name Black Sox after failing to pay their taxes in 1930.50 While the Sox were a mediocre team all year, Holloway’s season was packed with highlights. On May 30, in a doubleheader sweep of the Detroit Stars, he smacked a three-run homer and stole a base while covering center field and batting second for the Sox.51 On June 18, in a twin-bill split with the Chicago American Giants, Holloway’s brilliant play in the outfield was pointed out by the Baltimore Afro-American: “Crush Holloway proved a thorn in the side of the Giants, accepting five chances without an error, two of which were difficult running catches and one of which he took off the centerfield fence.”52 In a three-game sweep of the Detroit Stars at the end of June, Holloway was once again praised for his fielding, but also made his presence known with the lumber with six hits, including a double and two triples.53 On July 23 the Sox clobbered the Bacharach Giants, outscoring them 28-11 and outhitting them 36-22 in a doubleheader massacre that featured six hits and five runs from Holloway.54 The dog days of summer certainly didn’t slow him down as he swatted five hits in six at-bats in a 17-13 loss to the Philadelphia Stars on July 30.55

Holloway, by now 37 years old, labored through a disastrous 1934 season with the next-to-last-place Philadelphia Bacharach Giants. He hit a meager .141 in 17 games. The next season he was relegated to backup status, splitting the season between the New York Black Yankees and the Brooklyn Eagles. As luck would have it, Holloway enjoyed one last hurrah when in 1936 he latched on with the New York Crusaders, one of the leading black traveling clubs in the East.56 The Crusaders were a rag-tag bunch led by manager-pitcher Connie “Broadway” Rector, a 22-year veteran of the Negro Leagues. Besides Holloway, this fascinating team featured Dick Lundy, George Britt, Johnny “Schoolboy” Taylor, and Henry Spearman.57 This is most likely the team Holloway was referring to when he told John Holway, “I retired in 1937. I was playing up in Albany, New York, then. We had one colored team in the league and all the rest were white, but we won the championship.”58

Holloway seemed to be sipping from the fountain of youth while playing for the Brooklyn Royal Giants, also in 1936, when, in a doubleheader on June 21 against Bay Ridge, he swatted six hits in 10 at-bats with five runs and two stolen bases.59 Even more unlikely, in early September, once again in a doubleheader against Bay Ridge, Holloway stroked four hits, but this time with an amazing three stolen bases on tired, 39-year-old legs.60

Holloway didn’t hang up his spikes for good in 1937 as he claimed. He showed up in a box score for a team mysteriously called the Baltimore Black Sox in an early July 1939 16-1 loss to a New Jersey-based team, the Long Branch Greys. Baltimore’s lone run is mentioned as “a prodigious circuit clout by Crush Holloway, Baltimore’s touted slugger in the third round.”61 Oddly, there is, no known record of a Baltimore Black Sox team existing in 1939 outside of this newspaper reference. Holloway finally called it quits after what appears to be an emergency start for the Baltimore Elite Giants in a doubleheader played against the New York Cubans on August 27, 1939. In a game that was scheduled on the same day as the East-West All-Star contest, the 42-year-old Baltimore native Holloway filled in for all-star-bound Wild Bill Wright in right field for the Elites. Holloway proved to still have some thump left in his bat as he banged out at least two run-scoring flies, including a 400-foot drive that took a spectacular grab by center fielder José Vargas to rob him of a hit.62 The Elite Giants upset the heavily favored Homestead Grays to win the championship that year, but Holloway was not around to enjoy it.

After his playing days were through, Holloway stayed in the game by umpiring for the Baltimore Elite Giants, but threats from players and shamefully low pay led him to be disillusioned with the profession quickly enough to state, “To umpire in the Negro National League is not a life’s ambition of mine.” Umpires’ jobs were also subject to the whims of team owners who could easily let go of an umpire who ruled a close play against his team.63 In June of 1947 the NNL requested that the Elite Giants stop using Holloway as an umpire effectively ending his career. NNL Vice President Alex Pompez accused Holloway of “action detrimental to the best interests of the game” in explaining his actions.64

Holloway was always regarded as a sharp dresser, and in April 1951 he was recognized as the “best dressed man” at an Easter parade in Baltimore.65 Holloway and his wife, Buelah, settled down in Baltimore and ran a tailor shop together. They were married in 1921, but don’t appear to have had any children.66

Crush Holloway died on June 24, 1972, from cancer and is buried at the Mount Calvary Cemetery in Baltimore, Maryland. When standout Negro League first baseman Dave “Showboat” Thomas was asked in 1944 to fill out his all-time team, he chose Holloway as his right fielder.67 Sportswriter Marion Jackson, writing for the Atlanta Daily World in 1971, listed Holloway, along with familiar names like Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, Buck Leonard, Ray Dandridge, Vic Harris, and Cannonball Redding as players he thought should be enshrined in Cooperstown.68 There is no doubt that Holloway was one of the top outfielders of his era and undeniably one of the all-time greats on the basepaths.

When speaking about his time in the Negro Leagues just two months before his death in 1972, Holloway told John Holway: “Those were great players back then. But nobody knows about us anymore. If you put all these stories in the sporting pages, they could read all about it and understand how it was. But that’s lost history, see? It’s just past, that’s all. Nobody’s going to dig it up.”69 Thankfully, Mr. Holloway was wrong about that. One just wishes he could have been around to see it.

Sources

All statistics, unless otherwise noted, are from Seamheads.com.

Notes

1 Phil Dixon, The Negro Baseball Leagues: A Photographic History (Mattituck, New York: Amereon Ltd., 1992), 145.

2 Richard Bak, Turkey Stearnes and the Detroit Stars: The Negro Leagues in Detroit, 1919-1933 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1995), 189.

3 Bob Luke, Pete Hill: Black Baseball’s First Superstar (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2023), 146.

4 Most sources list Holloway’s birthdate as September 15 although there are some discrepancies regarding the year. On his World War I draft registration card, it’s listed as 1896, but on his World War II draft card it’s listed as 1899.

5 John Holway, Voices From the Great Black Baseball Leagues (New York: Da Capo Press Inc., !992), 62. Hereafter: Voices.

6 Ancestry.com.

7 Voices, 63.

8 Voices, 63.

9 Voices, 64.

10 Voices, 62-63.

11 Voices, 64.

12 “A Dozen Black Aces Sure Make a Winning Hand,” San Antonio Evening News, September 12, 1919: 11.

13 “Black Aces and Marines Split Games,” San Antonio Evening News, July 5, 1919: 11.

14 Edwin Ocasio-Lopez, “San Antonio Black Aces” (San Antonio: Texas A&M University-San Antonio, 2020), 14.

15 Ocasio-Lopez, 15-16.

16 Paul Debono, The Indianapolis ABCs: History of a Premier Team in the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 1997), 87-89.

17 Voices, 66.

18 “A.B.C. Team Has Two New Infielders for 1921 Club,” Indianapolis News, April 11, 1921: 18.

19 John Holway, Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books, 1988), 221.

20 Jeremy Beer, Oscar Charleston: The Life and Legend of Baseball’s Greatest Forgotten Player (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019), 133.

21 Debono, The Indianapolis ABCs, 141.

22 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2002), 12.

23 McNeil, 237.

24 McNeil, 14.

25 McNeil, 112.

26 Neil Lanctot, Fair Dealing & Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1910-1932 (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1994), 107.

27 Voices, 67.

28 Bernard McKenna, The Baltimore Black Sox: A Negro Leagues History, 1913-1936 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2020), 108-109.

29 Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2003), 44, 45, 75, 353.

30 McKenna, The Baltimore Black Sox, 110.

31 “Second Best,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 24, 1926: 6; “Three Additions Would Give Sox Greatest Team in Loop,” Baltimore Afro-American, March 27, 1926: 7.

32 “The Charleston Deal Is Off,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 30, 1927: 15.

33 “Black Sox Win Double Header,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 12, 1928: A6.

34 Jim Bankes, The Pittsburgh Crawfords (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2001), 86.

35 Lanctot, Fair Dealing & Clean Playing, 150.

36 “Hilldale Defeats Baltimore Black Sox,” New York Age, August 1, 1931: 6.

37 Kyle P. McNary, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe: 36 Years of Pitching & Catching in Baseball’s Negro Leagues (St. Louis Park, Minnesota: McNary Publishing, 1994), 152-153.

38 Voices, 60.

39 “The Stamp of Approval Awaits Warfield at Balto.,” Philadelphia Tribune, March 14, 1929: 10.

40 W. Rollo Wilson, “Sport Shots: Popular Kid Chocolate,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 16, 1929: A4.

41 “Smith Heads American Negro League in Final Averages,” New York Amsterdam News, September 25, 1929: 12.

42 “DeMoss Takes His Detroit Stars to Balmy Nashville,” Chicago Defender, April 12, 1930: 8.

43 “Sox and Grays Split Bill,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 18, 1931: 12.

44 W. Rollo Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 18, 1931: A4.

45 “Black Sox in League Lead,” New York Amsterdam News, May 25, 1932: 13.

46 “Johnson, Tolan, Dues Score in Olympic Tests,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 9, 1932: 15.

47 John B. Holway, Josh and Satch: The Life and Times of Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige (New York, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1991), 50.

48 “Black Yankees Win Series,” Baltimore Afro-American, March 11, 1933: 16.

49 William F. McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season: Pay for Play Outside of the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2007), 114.

50 McKenna, The Baltimore Black Sox, 152.

51 “Sox Enter Win Column, Beat Detroit Twice,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 10, 1933: 16.

52 “Sox Take Chicago,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 24, 1933: 17.

53 “Sox Move Up by Taking Series From Detroit,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 1, 1933: 16.

54 “Sox Pound Four Bacharach Hurlers to Win Twin Bill,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 29, 1933: 16.

55 “Stars Win From Sox Both Ends of Double Bill,” Baltimore Afro-American. August 5, 1933: 21.

56 “Pilot Drops Nolan Vamps,’” Mount Vernon (New York) Argus, May 28, 1936: 23.

57 “Allendale A’s Play New York Crusaders,” Allentown (Pennsylvania) Morning Call, May 22, 1936: 28.

58 Voices, 68.

59 “Bay Ridge Has Faith in Team Despite Losses,” Brooklyn Times Union, June 22, 1936: 11.

60 “Bay Ridge Wins Double-Header,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 9, 1936: 40.

61 “Long Branch Nine Drives Out 17 Blows to Crush Black Sox for Third Straight Victory,” Asbury Park Press, July 7, 1939: 13.

62 Ralph F. Boyd, “Elites and Cubans Split Twin Bill,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 2, 1939: 23.

63 “Dan Burley’s ‘Confidentially Yours,’” New York Amsterdam News, October 27, 1945: 14.

64 “Washington’s Bat Gives Locals Win,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 7, 1947: 17.

65 “On the Avenue,” Baltimore Afro-American, April 14, 1951: 9.

66 Voices, 60.

67 “Dan Burley’s ‘Confidentially Yours,’” New York Amsterdam News, May 27, 1944: 6B.

68 “Views Sports of the World,” Atlanta Daily World, July 1, 1971: 12.

69 Voices, 69.

Full Name

Crush Christopher Columbus Holloway

Born

September 15, 1896 at Hillsboro, TX (USA)

Died

June 24, 1972 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.