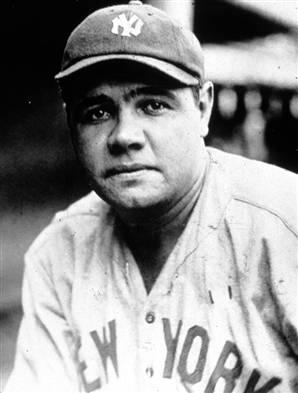

Babe Ruth

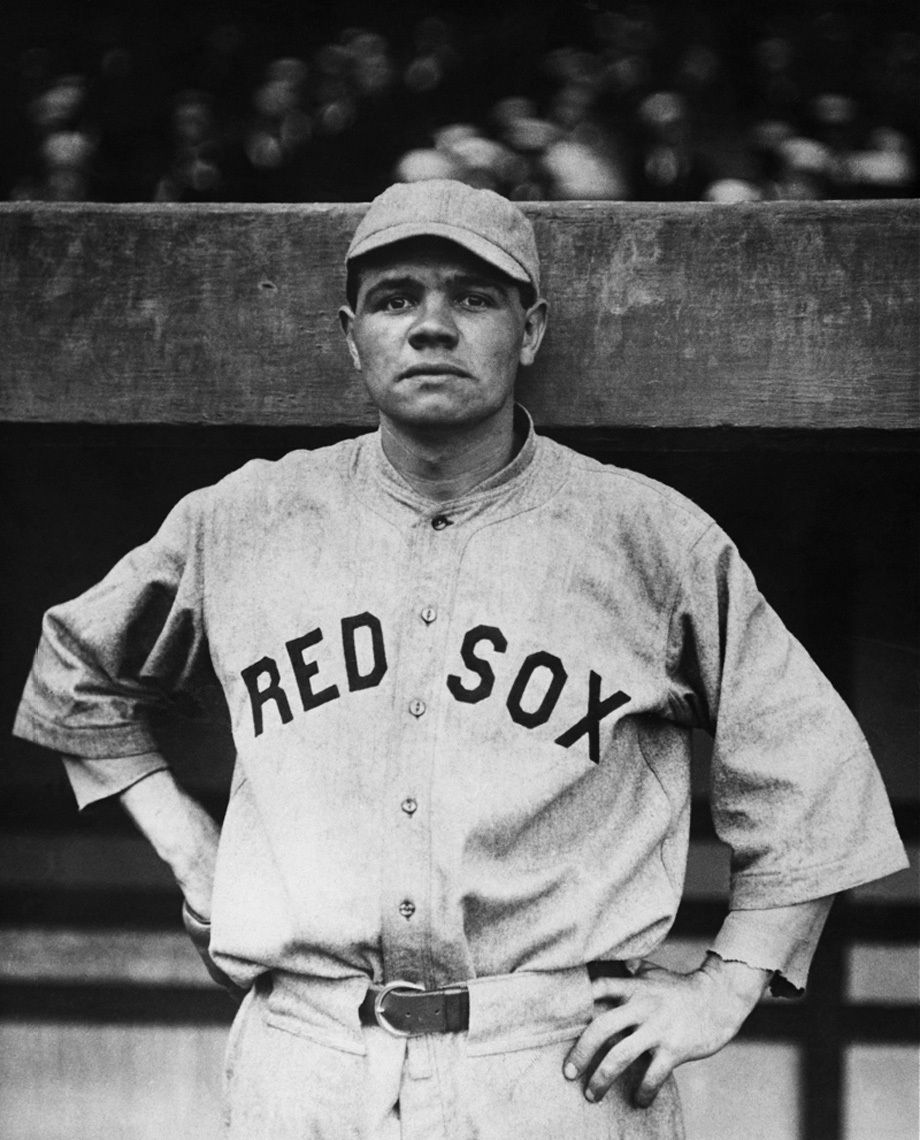

During his five full seasons with the Boston Red Sox, Babe Ruth established himself as one of the premier left-handed pitchers in the game, began his historic transformation from moundsman to slugging outfielder, and was part of three World Series championship teams. After he was sold to the New York Yankees in December 1919, his eye-popping batting performances over the next few seasons helped usher in a new era of long-distance hitting and high scoring, effectively bringing down the curtain on the Deadball Era.

During his five full seasons with the Boston Red Sox, Babe Ruth established himself as one of the premier left-handed pitchers in the game, began his historic transformation from moundsman to slugging outfielder, and was part of three World Series championship teams. After he was sold to the New York Yankees in December 1919, his eye-popping batting performances over the next few seasons helped usher in a new era of long-distance hitting and high scoring, effectively bringing down the curtain on the Deadball Era.

George Herman Ruth was born to George Ruth and Catherine Schamberger on February 6, 1895, in his mother’s parents’ house at 216 Emory Street, in Baltimore, Maryland. With his father working long hours in his saloon and his mother often in poor health, Little George (as he was known) spent his days unsupervised on the waterfront streets and docks, committing petty theft and vandalism. Hanging out in his father’s bar, he stole money from the till, drained the last drops from old beer glasses, and developed a taste for chewing tobacco. He was only six years old.

Shortly after his seventh birthday, the Ruths petitioned the Baltimore courts to declare Little George “incorrigible” and sent him to live at St. Mary’s Industrial School, on the outskirts of the city. The boy’s initial stay at St. Mary’s lasted only four weeks before his parents brought him home for the first of several attempted reconciliations; his long-term residence at St. Mary’s actually began in 1904. But it was during that first stay that George met Brother Matthias.

“He taught me to read and write and he taught me the difference between right and wrong,” Ruth said of the Canadian-born priest. “He was the father I needed and the greatest man I’ve ever known.”1 Brother Matthias also spent many afternoons tossing a worn-out baseball in the air and swatting it out to the boys. Little George watched, bug-eyed. “I had never seen anything like that in my life,” he recalled. “I think I was born as a hitter the first day I ever saw him hit a baseball.”2 The impressionable youngster imitated Matthias’s hitting style—gripping the bat tightly down at the knobbed end, taking a big swing at the ball — as well as his way of running with quick, tiny steps.

When asked in 1918 about playing baseball at St. Mary’s, Ruth said he had little difficulty anywhere on the field. “Sometimes I pitched. Sometimes I caught, and frequently I played the outfield and infield. It was all the same to me. All I wanted was to play. I didn’t care much where.”3 In one St. Mary’s game in 1913, Ruth, then 18 years old, caught, played third base (even though he threw left-handed), and pitched, striking out six men, and collecting a double, a triple, and a home run. That summer, he was allowed to pitch with local amateur and semipro teams on weekends. Impressed with his performances, Jack Dunn signed Ruth to his minor-league Baltimore Orioles club the following February.

Although he was a bumpkin with minimal social skills, at camp in South Carolina Ruth quickly distinguished himself on the diamond. That spring, the Orioles played several major league teams. In two outings against the Phillies, Ruth faced 29 batters and allowed only six hits and two unearned runs. The next week, he threw a complete game victory over the Philadelphia Athletics, winners of three of the last four World Series. Short on cash that summer, Dunn sold Ruth to the Boston Red Sox.

On July 11, 1914, less than five months after leaving St. Mary’s, Babe made his debut at Fenway Park: he pitched seven innings against Cleveland and received credit for a 4-3 win. After being hit hard by Detroit in his second outing, Ruth rode the bench until he was demoted to the minor leagues in mid-August, where he helped the Providence Grays capture the International League pennant. Ruth returned to Boston for the final week of the 1914 season. On October 2, he pitched a complete game victory over the Yankees and doubled for his first major-league hit.

Babe spent the winter in Baltimore with his new wife, Boston waitress Helen Woodford, and in 1915, he stuck with the big club. Ruth slumped early in the season, in part because of excessive carousing with fellow pitcher Dutch Leonard, and a broken toe — sustained by kicking the bench in frustration after being intentionally walked — kept him out of the rotation for two weeks. But when he returned, he shined, winning three complete games in a span of nine days in June. Between June 1 and September 2, Ruth was 13-1 and ended the season 18-8.

In 1916, Ruth won 23 games and posted a league-leading 1.75 ERA. He also threw nine shutouts—an American League record for left-handed pitchers that still stands (it was tied in 1978 by the Yankees’ Ron Guidry). In Game Two of the World Series, Ruth pitched all 14 innings, beating the Brooklyn Dodgers, 2-1. Boston topped Brooklyn in the series four games to one.

Ruth’s success went straight to his head in 1917, and he began arguing with umpires about their strike zone judgment. Facing Washington on June 23, Ruth walked the first Senators batter on four pitches. Feeling squeezed by home plate umpire Brick Owens, Ruth stormed off the mound and punched Owens in the head. After Ruth was ejected, Ernie Shore came in to relieve. The baserunner was thrown out trying to steal and Shore retired the next 26 batters. Ruth got off lightly with a 10-day suspension and a $100 fine. He ended the year with a 24-13 record, completing 35 of his 38 starts, with six shutouts and an ERA of 2.01.

Although Ruth didn’t play every day until May 1918, the idea of putting him in the regular lineup was first mentioned in the press during his rookie season. Calling Babe “one of the best natural sluggers ever in the game,” Washington sportswriter Paul Eaton thought Ruth “might even be more valuable in some regular position than he is on the slab — a free suggestion for Manager [Bill] Carrigan.”4 The Boston Post reported that summer that Babe “cherishes the hope that he may someday be the leading slugger of the country.”5

In 1915, Ruth batted .315 and topped the Red Sox with four home runs. Braggo Roth led the AL with seven homers, but he had 384 at-bats compared to Babe’s 92. Ruth didn’t have enough at-bats to qualify, but his .576 slugging percentage was higher than the official leaders in the American League (Jack Fournier .491), the National League (Gavvy Cravath .510), and the Federal League (Benny Kauff .509).

With the Red Sox offense sputtering after the sale of Tris Speaker in 1916, the suggestion to play Ruth every day was renewed when he tied a record with a home run in three consecutive games. Ruth hated the helpless feeling of sitting on the bench between pitching assignments, and believed he could be a better hitter if given more opportunity. In mid-season, with all three Boston outfielders in slumps, Carrigan was reportedly ready to give Babe a shot, but it never happened.6 Ruth finished the 1917 season at .325, easily the highest average on the team. Left fielder Duffy Lewis topped the regulars at .302; no one else hit above .265. Giving Ruth an everyday job remained nothing more than an entertaining game of “what if” — until 1918.

The previous summer, the United States had entered the Great War; many players had enlisted or accepted war-related jobs before the season began. Trying to strengthen the Red Sox offense, about two weeks into the season, manager Ed Barrow, after discussions with right fielder and team captain Harry Hooper, penciled Ruth into the lineup. The move came only a few days after a Boston paper reported that team owner Harry Frazee had refused an offer of $100,000 for Ruth. “It is ridiculous to talk about it,” Frazee said. “Ruth is our Big Ace. He’s the most talked of, most sought for, most colorful ball player in the game.”7 Later reports revealed that the offer had come from the Yankees.8

On May 6, 1918, in the Polo Grounds against the Yankees, Ruth played first base and batted sixth. It was the first time he had appeared in a game other than as a pitcher or pinch-hitter and the first time he batted in any spot other than ninth. Ruth went 2-for-4, including a two-run home run. At that point, five of Ruth’s 11 career home runs had come in New York. The Boston Post’s Paul Shannon began his game story, “Babe Ruth still remains the hitting idol of the Polo Grounds.”9

The next day, against the Senators, Ruth was bumped up to fourth in the lineup — and he hit another home run — where he stayed for most of the season. Barrow also wanted Ruth to continue pitching, but Babe, enjoying the notoriety his hitting was generating, often feigned exhaustion or a sore arm to avoid the mound.10 The two men argued about Ruth’s playing time for several weeks. Finally, after one heated exchange in early July, Ruth quit the team. He returned a few days later and, after renegotiating his contract with Frazee to include some hitting-related bonuses, patched up his disagreements with Barrow.

“I don’t think a man can pitch in his regular turn, and play every other game at some other position, and keep that pace year after year,” Ruth said. “I can do it this season all right, and not feel it, for I am young and strong and don’t mind the work. But I wouldn’t guarantee to do it for many seasons.”11 Ruth then began what is likely the greatest nine- or ten-week stretch of play in baseball history. From mid-July to early September 1918, Ruth pitched every fourth day, and played either left field, center field, or first base on the other days. Ruth’s double duty was not unique during the Deadball Era — a handful of players had done both — but his level of success was (and remains) unprecedented.12

In one 10-game stretch at Fenway, Ruth hit .469 (15-for-32) and slugged .969 with four singles, six doubles, and five triples. He was remarkably adept at first base, his favorite position. On the mound, he allowed more than two runs only once in his last ten starts. The Colossus, as Babe was known in Boston, maintained his status as a top pitcher while simultaneously becoming the game’s greatest hitter.

Ruth’s performance led the Red Sox to the American League pennant, in a season cut short by the owners, partially because of dwindling attendance. All draft-age men were under government order to either enlist or take war-related employment — in shipyards or munitions factories, for example — which led to paltry turnouts of less than 1,000 for many afternoon games that summer.

Ruth opened the World Series on September 5 against the Chicago Cubs with a 1-0 shutout. He pitched well in Game Four, despite having bruised his left hand during some horseplay on the train back to Boston, and his double drove in what turned out to be the winning runs. Those performances, together with his extra-inning outing in 1916, gave Ruth a record of 29⅔ consecutive scoreless World Series innings, one of the records Ruth always said he was most proud of.13 His streak was finally broken by Whitey Ford of the Yankees in the 1960s.

Ruth opened the World Series on September 5 against the Chicago Cubs with a 1-0 shutout. He pitched well in Game Four, despite having bruised his left hand during some horseplay on the train back to Boston, and his double drove in what turned out to be the winning runs. Those performances, together with his extra-inning outing in 1916, gave Ruth a record of 29⅔ consecutive scoreless World Series innings, one of the records Ruth always said he was most proud of.13 His streak was finally broken by Whitey Ford of the Yankees in the 1960s.

While with the Red Sox, Ruth often arranged for busloads of orphans to visit his farm in Sudbury for a day-long picnic and ball game, making sure each kid left with a glove and autographed baseball. When the Red Sox were at home, Ruth would arrive at Fenway Park early on Saturday mornings to help the vendors—mostly boys in their early teens—bag peanuts for the upcoming week’s games.

“He’d race with us to see who could bag the most,” recalled Tom Foley, who was 14 years old in 1918. (Ruth was barely out of his teens himself.) “He’d talk a blue streak the whole time, telling us to be good boys and play baseball, because there was good money in it. He thought that if we worked hard enough, we could be as good as he was. But we knew better than that. He’d stay about an hour. When we finished, he’d pull out a $20 bill and throw it on the table and say ‘Have a good time, kids.’ We’d split it up, and each go home with an extra half-dollar or dollar depending on how many of us were there. Babe Ruth was an angel to us.”14

To management, however, Ruth was a headache. His continued inability — or outright refusal — to adhere to the team’s curfew earned him several suspensions and his non-stop salary demands infuriated Frazee. The Red Sox owner had spoken publicly about possibly trading Ruth before the 1919 season, when Babe was holding out for double his existing salary and threatening to become a boxer. However, Ruth and Frazee came to terms and the Babe’s hitting made headlines across the country all season long. He played 110 games in left field, belted a record 29 home runs, and led the major leagues in slugging percentage (.657), on-base percentage (.456), runs scored (103), RBIs (113), and total bases (284). He also drove in or scored one-third of Boston’s runs. But while Ruth also won nine games on the mound, the rest of the staff fell victim to injuries and the defending champs finished in the second division with a 66-71 record.

The sale of Ruth to the Yankees was announced after New Year’s 1920 and although it was big news, public opinion in Boston was divided. Many fans were aghast that such a talent would be cast off, while others, including many former players, insisted that a cohesive team (as opposed to one egomaniac plus everyone else) was the key to success.15

“While Ruth, without question, is the greatest hitter that the game has ever seen, he is likewise one of the most selfish and inconsiderate men that ever wore a baseball uniform,” Frazee explained. “Had he possessed the right disposition, had he been willing to take orders and work for the good of the club like the other men on the team, I would never have dared let him go.”16 And despite Ruth’s record-setting (and attention-grabbing) 29 home runs, the Red Sox had finished in sixth place. Frazee considered the long balls “more spectacular than useful.”17

He also intimated that the Yankees were taking a gamble on Ruth. It was a statement he would be later ridiculed for, but at the time the Yankees felt the same way. The amount paid ($100,000) was astronomical, Ruth ate and drank excessively, frequented prostitutes, and had been involved in several car accidents. It would have surprised no one if, for whatever reason, Ruth was out of baseball in a year or two.

Amidst this speculation over his future, on February 28, 1920, Babe Ruth left Boston and boarded a train for New York, on his way to spring training in Florida. He was still just 25 years old.

* * *

Babe Ruth arrived in New York City at the best possible time for his outsized hitting and hedonistic lifestyle. It was the Roaring Twenties, the Jazz Age, a time of individualism, more progressive social and sexual attitudes, and a greater emphasis on the pursuit of pleasure. (Prohibition, instituted in 1920, had no effect whatsoever.) Sportswriter Westbrook Pegler called it “the Era of Wonderful Nonsense.”18

It was also a time when “trick pitches” — the emeryball, the spitter, and various ways of scuffing the ball — were outlawed. Both leagues began using a better quality (i.e., livelier) baseball. Ruth thrived — and over time, so did the players in both leagues.

The Babe got off to a slow start in 1920. He was in spring training for nearly three weeks before he crushed his first home run. Ruth also jumped into the stands to fight a fan who had called him “a big piece of cheese” (probably not a direct quote).19 While tracking a fly ball during an exhibition game in Miami, Ruth ran into a palm tree in center field and was knocked unconscious.

After a disappointing April, in which he missed time due to a strained right knee, Ruth began May with home runs in consecutive games against the Red Sox. He went on to set a major league record for the month with 11 homers. That record lasted less than 30 days, when he smacked 13 long balls in June. He tied his own single-season record of 29 home runs — set the previous year with Boston — on July 16. Two weeks later, he had 37.

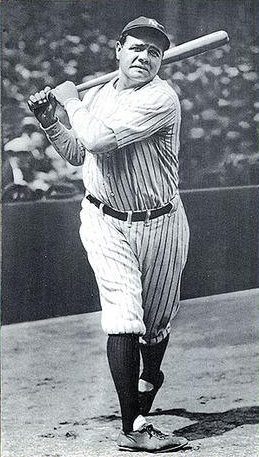

He finished the year with the unfathomable total of 54 home runs. He outhomered 14 of the other 15 major league teams. The AL runner-up was George Sisler, with 19; Cy Williams needed only 15 to top the National League. Ruth hit 14.6% of the American League’s 369 home runs. For Barry Bonds to outdistance his peers in 2001 (when he set a new single-season mark of 73 home runs) as Ruth did in 1920, Bonds would have needed to hit 431 homers. In addition to this stunning display of power, Ruth was fourth in batting average at .376. His slugging percentage of .847 stood for more than 80 years — until Bonds reached .863 in 2001.

Ruth’s arrival in New York began a stretch of offensive dominance the game will likely never see again. In the 12 seasons between 1920 and 1931, Ruth led the AL in slugging 11 times, home runs 10 times, walks nine times, on-base percentage eight times, and runs scored seven times. His batting average topped .350 eight times. In exactly half of those 12 seasons, he batted over .370. (Ruth once said that if he shortened his swing and tried to hit singles, he’d hit .600.20)

Ruth’s effect on the national game was nothing short of revolutionary. Leigh Montville, author of The Big Bam, wrote that Ruth’s teammates reacted with the same sense of wonder as everyone else in America. “They never had seen anything like it. The game they had learned was being changed in front of their faces.”21

Ruth also starred in a short movie entitled Headin’ Home, which was filmed in Fort Lee, New Jersey. The plot, such as it was, starred Babe as a country bumpkin who makes good in big league ball — not exactly playing against type. According to Variety, “It couldn’t hold the interest of anyone for five seconds if it were not for the presence of” Ruth.22 Babe often returned to the Polo Grounds after a morning of filming still wearing his movie makeup and mascara, much to the annoyance of manager Miller Huggins.23

During his final season in Boston, Ruth played most of his games in left field. When he joined the Yankees, and began playing his home games at the Polo Grounds, he played all three outfield positions. In 1920, Ruth started 84 games in right, 31 in left, and 25 in center. The following season, he was almost exclusively used in left, starting 132 of 150 games; he didn’t play even one inning in right field. Once the Yankees moved into their own stadium in the Bronx, Ruth generally played right field at home and left field on the road. Although the Babe is remembered as mainly a right fielder, he started nearly as many games in left (1,040) during his career as he did in right (1,122).24

Ruth quickly became one of the most famous people in the country. On Yankees road trips, people with no interest in baseball traveled hundreds of miles to get a glimpse of the Babe. He was cheered wildly in every park — for rival fans, if Ruth smacked one out of the park, it hardly seemed to matter what the final score was.

Sunday baseball became legal in New York in 1919 and the fan base changed forever. Women and children came out regularly to the park. One of Ruth’s most enduring nicknames — the Bambino — came from the Italian fans in the upper Manhattan neighborhood around the Polo Grounds.

Everyone wanted to know as much about Ruth as possible. The New York papers (more than 15 English-language dailies) began devoting more and more space to the Babe’s exploits. Nothing was too trivial. According to sportswriter Tom Meany, if Ruth was seen “taking an aspirin, it was practically a scoop for the writer who saw him reach for the sedative.”25 Marshall Hunt was hired by the Daily News to write about the Babe — and only the Babe — 365 days a year.26

“There was no such thing as no news with the Babe. … The Speed Graphic, the newspaper photographer’s camera of choice, loved his broad face with its flat nose and tiny eyes, loved his absolutely unique look, features put together in a hurry, an out-of-focus bulldog, no veneer or sanding involved. This was a face that soon was instantly recognizable, seen again and again … The Babe was an incorrigible, wondrous part of everyone’s family. … He was the life of everybody’s party. … Laughing but earnest men in fedoras and off-the-rack suits, sportswriters, watched the sun rise and fall on his big head and were moved to grand statements. They typed the legend into place, adding layer upon layer of adjectives until often the man in the middle couldn’t even be seen.”27

In the 1920s, these giddy sportswriters were coming up with nicknames for Ruth nearly every day. His Boston nickname — the Colossus — morphed into the Colossus of Clout. From there, a seemingly endless — and often silly — list emerged: the Wizard of Wham, the Maharajah of Mash, the Rajah of Rap, the Caliph of Clout, the Sultan of Swat, the Behemoth of Bash, the Bazoo of Bang, the Potentate of Pow, the Wali of Wallop, the Prince of Pounders, and on and on.

His own name became a nickname, bestowed on someone who was the best in his or her field: the Babe Ruth of Surfing, the Babe Ruth of Bowling, the Babe Ruth of Poker. His last name became an adjective: “Ruthian,” defined as “colossal, dramatic, prodigious, magnificent; with great power.”28 His teammates usually called him “Jidge” (for George).

The Yankees finished the 1920 season in third place with a 95-59 record, only three games behind Cleveland. It was their best showing in 10 years. They followed that up in 1921 by winning 98 games and their first-ever pennant. And somehow Ruth may have actually had a better year at the plate than he did in 1920. His batting average improved slightly (.376 to .378), and while his OBP (.532 to .512) and slugging (.847 to .846) dipped slightly, he drove in 168 runs and hit a career-high 16 triples. (According to manager Huggins, Ruth was the second-fastest player on the team.29) He also broke his own single-season home run record — for the third consecutive year — with 59. On July 18, Ruth became the game’s career home run leader, hitting his 139th homer, passing Roger Connor. Ruth also set new season records for runs scored (177), extra base hits (119), and total bases (457) — three achievements that no player has yet matched.

Ruth also pitched in two games. On June 13, he allowed four runs in five innings. He also hit two home runs that day and finished the game in center field as the Yankees won, 13-8.

In September 1921, Ruth underwent three hours of tests at Columbia University to determine his athletic and psychological capabilities. Sportswriter Hugh Fullerton wrote up the findings for Popular Science Monthly:

“The tests revealed the fact that Ruth is 90 per cent efficient compared with a human average of 60 per cent. That his eyes are about 12 per cent faster than those of the average human being. That his ears function at least 10 per cent faster than those of the ordinary man. That his nerves are steadier than those of 499 out of 500 persons. That in attention and quickness of perception he rated one and a half times above the human average. That in intelligence, as demonstrated by the quickness and accuracy of understanding, he is approximately 10 per cent above normal.”30

The psychologists also discovered that Ruth did not breathe during his entire swing. They stated that if he kept breathing while swinging, he could generate even more power.

The Yankees faced their co-tenants in the Polo Grounds, the New York Giants, in the 1921 World Series. Ruth cut his left arm (which then became infected) during a slide in the second game and wrenched his knee in the fifth game. Babe made only one pinch-hitting appearance in the final three contests. The Yankees won the first two games, but the Giants took the best-of-nine series, five games to three.

After the World Series, Ruth and some other Yankees went on a barnstorming tour to earn extra money. This was in violation of the National Commission’s 1911 edict that players on the two pennant-winning teams could not barnstorm after the World Series — enacted, perhaps, to preserve the integrity of the World Series or to limit the players’ total income. Kenesaw Mountain Landis, newly installed as the game’s first commissioner, suspended Ruth and fellow outfielder Bob Meusel for the first six weeks of the season, and fined them each $3,362 — the amount of their 1921 World Series share.

When Ruth returned to the lineup on May 20, he was also named as the team’s captain, succeeding Hal Chase (1912) and Roger Peckinpaugh (1914-21). The honor lasted less than one week. Ruth was again slow to get his bat started and after five games, he was hitting .095 and being booed.

On May 25, he was thrown out trying to stretch a single into a double and, furious at the call, threw dirt in umpire George Hildebrand’s face. On his way towards the dugout, he spied a heckler and jumped into the stands, ready to fight. The fan ran away and Ruth ended up standing on the dugout roof, screaming, “Come on down and fight! Anyone who wants to fight, come down on the field!”31 Ruth was fined $200 and was replaced as captain by shortstop Everett Scott.

Babe was also suspended for three days in mid-June for his part in an obscenity-laced tirade against umpire Bill Dinneen. When Ruth got the news the following day, he challenged Dinneen to a fist fight—and the suspension was increased to five days.32 In the wake of the suspensions, Ruth made an effort to check his temper. On June 26, as some of his teammates argued with Dinneen, Babe merely sat down in the outfield grass and watched.33

Ruth played in only 110 games in 1922. His batting average dropped to .315, but he led the league with a .672 slugging percentage and his OBP of .434 was fourth-best.

The Yankees and the Giants met in the World Series for the second straight year. After a three-year experiment as a best-of-nine, the series was back to being a best-of-seven, where it has remained to the present day. The Giants swept the Yankees in five games (Game Two ended in a tie due to darkness). Ruth went 2-for-17.

The Yankees left the Polo Grounds and began 1923 in their own ballpark, directly across the Harlem River in the borough of the Bronx. Yankee Stadium was dubbed the House that Ruth Built, but with its short right-field porch, a more appropriate title might be the House Built for Ruth. Babe returned to his battering ways with a vengeance. He hit .393—if only four of his 317 outs had fallen for hits, he would have batted .400—and hit 41 home runs. Harry Heilmann of the Tigers led the AL with a .403 average.

The Yankees won their third straight pennant, finishing 16 games ahead of the Tigers. And for the third straight year, the World Series was an all-New York affair. This time, it was the Yankees, after losing two of the first three games, who prevailed. Ruth went 7-for-19 in the Series, with three home runs. However, all three came at the Polo Grounds. Giants’ outfielder Casey Stengel hit the first World Series home run at Yankee Stadium.

Ruth won his only batting title in 1924, easily topping the AL at .378—almost 20 points higher than Charlie Jamieson’s .359. Babe hit 46 home runs and tied for second with 124 RBIs. His .739 slugging percentage was more than 200 points higher than runner-ups Harry Heilmann and Ken Williams (both at .533). However, the Yankees finished in second place, two games behind the Washington Senators.

In 1925, the Yankees fell all the way to seventh, 69-85, 28½ games out of first place. It was a bad year from the start. Ruth showed up for spring training at 256 pounds and went on to have the worst year of his career. He hit .290/.393/.543 (batting/on-base/slugging), with 25 home runs and a paltry 67 RBIs. This was also the year Ruth suffered what W.O. McGeehan of the New York Tribune famously called “The Bellyache Heard ‘Round the World.”34 Ruth fell ill during the team’s spring training exhibition tour. The initial story was that Ruth had eaten too many hot dogs, and the New York Evening Journal ran a photo of Ruth with 12 numbered franks superimposed on his stomach.35

However, it was clearly more serious than indigestion or a matter of Ruth being “run down and [having] low blood pressure,” as the Yankees’ team doctor claimed.36 On April 17, Ruth had minor surgery for what doctors termed an “intestinal abscess”37 and he did not return to the Yankees lineup until June. Several teammates hinted it might have been a sexually-transmitted disease; one teammate said it wasn’t a bellyache, “it was something a bit lower.”38

Whatever it was, it didn’t cramp Ruth’s style. Babe was staying out all night more often than not and by the end of the season, he was a physical wreck. In mid-December, Ruth realized if he wanted to continue playing ball into his thirties, he needed to do something different. He showed up at Artie McGovern’s gymnasium on East 42nd Street in Manhattan, a well-known gym used by New York’s rich and famous.39

Ruth committed himself to McGovern’s strict regimen of exercise, diet, and rest. Six weeks later, by the time he was ready to head south for spring training, Ruth had lost 44 pounds and shed almost nine inches from his waistline.40

The Babe still had plenty of fun, obviously, but he never let himself get seriously out of shape again. As Robert Creamer wrote in Babe: The Legend Comes to Life, “From 1926 through 1931, as he aged from thirty-two to thirty-seven, Ruth put on the finest sustained display of hitting that baseball has ever seen. During those six seasons, he averaged 50 home runs a year, 155 runs batted in and 147 runs scored; he batted .354. … From the ashes of 1925, Babe Ruth rose like a rocket.”41

As Ruth rose, so did the Yankees. The Bombers went from seventh place to first, winning 91 games and the 1926 pennant. Ruth batted .372/.516/.737, with 47 home runs (runner-up Al Simmons had 19), and drove in 153 (36 more than his nearest challenger). The Yankees were also boosted by the great play of two rookie infielders: second baseman Tony Lazzeri and shortstop Mark Koenig. First baseman Lou Gehrig, in his second full season at age 22, led the league with 20 triples and 83 extra-base hits — one more than Ruth.

In Game Four of the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, Ruth belted three home runs. It was the first time he had ever hit three in one game — and it was the first time that had been done in a World Series game. This was also the game before which Ruth allegedly promised to hit a home run for 11-year-old hospital patient Johnny Sylvester.

The 1926 Series came down to a deciding seventh game at Yankee Stadium. New York trailed 3-2 in the bottom of the ninth inning, when Ruth walked with two outs. Bob Meusel was facing Grover Cleveland Alexander when Ruth took off for second. He was thrown out trying to steal — ending the game and the World Series.

The 1927 Yankees are often talked about as the greatest team in baseball history. New York finished with a 110-44 record, winning the league by a whopping 19 games and sweeping the Pittsburgh Pirates in the World Series. They scored 976 runs, 131 more than second-best Detroit.

Ruth’s fabled 60 home runs — which he had become obsessed with since hitting 59 six years earlier — captured the headlines, but Gehrig, at age 24, had a better season. He outhit Ruth (.373 to .356) and nearly matched him in on-base percentage (.474 to .486), and slugging (.765 to .772). Gehrig had more extra base hits (117 to 97), total bases (447 to 417), and RBIs (173 to 165). He led the major leagues in doubles, RBIs, and total bases and was second in the American League in triples, home runs, hits, and batting average.

The Yankees won nine fewer games in 1928, but their 101-53 record was still good enough for a third straight pennant. Ruth batted only .323, but his 54 home runs helped him lead the major leagues in slugging at .709. The Yankees used only three pitchers as they swept the Cardinals in the World Series. Ruth batted .625 (10-for-16), with three doubles, three home runs, and a 1.375 slugging percentage. Gehrig hit .545 (6-for-11) and slugged 1.727.

In January 1929, Babe’s first wife, Helen, died in a house fire in Watertown, Massachusetts. At the time, Helen was living with Edward Kinder, a dentist, and while the deed on the house listed Helen and Kinder as husband and wife, they were not, in fact, married. (Babe and Helen had never officially divorced.) Ruth was devastated by the news. At the funeral, he wept uncontrollably.42

Babe married Claire Hodgson on April 17. The following day, the Yankees — with numbers on the back of their uniforms for the first time — opened the season against the Red Sox. Babe, wearing his new #3, whacked a first-inning home run to left field and doffed his cap to Claire as he rounded the bases.

On August 11 in Cleveland, Ruth hit the 500th home run of his career. The New York World called it “a symbol of American greatness.”43 The man who retrieved the homer got two signed baseballs and, after posing for a photo with Ruth, the Babe slipped him a $20 bill.44

Miller Huggins passed away suddenly near the end of the 1929 season — and Babe lobbied for the manager’s job for 1930. (Ruth would drop hints about wanting to manage for the next four years, but the Yankees never seriously considered it.) Ruth also asked for his salary to be increased to $100,000 — this coming a few months after Black Tuesday and the start of what became the Great Depression. He ended up signing a two-year deal for $80,000 per season. With exhibition game receipts, movie shorts, personal appearances, and endorsements, Ruth probably earned close to $200,000 in 1930.

By the end of June 1930, Ruth was ahead of his 60-homer pace of 1927, but injuries slowed him down and he finished with 49.

The Yankees were an offensive juggernaut. In both 1930 and 1931, they scored more than 1,000 runs — an average of nearly seven runs per game. But it was the Philadelphia Athletics who won the pennant in 1929, 1930, and 1931 behind the big bats of Jimmie Foxx and Al Simmons and the pitching of Lefty Grove.

In 1931, at age 36, Ruth had one of his finest seasons. He hit .373/.495/.700, with 46 home runs, 162 RBIs, 128 walks and 149 runs scored.

Ruth made his final trip to the World Series in 1932. Amazingly, in the seven-year reign of Ruth and Gehrig from 1929-1935, the Yankees won only one pennant. Gehrig (.349/.451/.621, 34 HR, 151 RBIs) and Ruth (.341/.489/.661, 41 HR, 137 RBIs) were ably assisted by Lazzeri, Bill Dickey, Ben Chapman and Earle Combs. However, it was Jimmie Foxx of the A’s who led the league in home runs (58).

Ruth made his final trip to the World Series in 1932. Amazingly, in the seven-year reign of Ruth and Gehrig from 1929-1935, the Yankees won only one pennant. Gehrig (.349/.451/.621, 34 HR, 151 RBIs) and Ruth (.341/.489/.661, 41 HR, 137 RBIs) were ably assisted by Lazzeri, Bill Dickey, Ben Chapman and Earle Combs. However, it was Jimmie Foxx of the A’s who led the league in home runs (58).

The Yankees swept the Chicago Cubs in the 1932 World Series, giving them wins in 12 straight World Series games. It was during the third game — October 1 at Wrigley Field — that Ruth added to his legend. The game was tied 4-4 when Ruth stepped in against Cubs starter Charlie Root with one out in the fifth inning. Ruth had already hit a three-run homer and flied to deep right, and the Cubs’ bench-jockeying was at a fever pitch.

Everyone agrees that as Root threw two called strikes to Ruth, the Babe held up one and two fingers. What exactly happened before Root threw his 2-2 pitch will never be definitively known. The legend says Ruth pointed towards the center field bleachers, indicating that was where he was going to hit the next pitch. Or he may have been saying “I’ve still got one strike left.” Or he was jawing with the hecklers in the Cubs’ dugout.

Either way, Ruth swung and belted the ball to deep center field — one of the longest home runs seen at Wrigley — for his second home run of the afternoon. He laughed as he jogged around the bases, pointing and jeering at the Cubs dugout.

Of the many game stories written that afternoon, only one (Westbrook Pegler) mentioned Ruth “calling his shot.”45 Within two or three days, however, writers who had initially made no reference to Ruth’s theatrics — and even a few who had not been in attendance at the park — were offering their own recollections. And thus a legend was born.46 A 16mm home movie of the at-bat surfaced in 1999. The grainy film does show Ruth pointing his arm, but it’s impossible to determine exactly what he is doing.

Root maintained that Ruth “did not point at the fence before he swung. If he had made a gesture like that, well, anybody who knows me knows that Ruth would have ended up on his ass.”47 As for the Babe, when asked whether he had really pointed to the bleachers, he smiled and said, “It’s in the papers, isn’t it?”48

It was Ruth’s last trip to the World Series. He played on seven World Series champions: four with the Yankees (1923, 1927, 1928, 1932), and three with the Red Sox (1915, 1916, 1918). He was also on the losing side of three World Series teams with New York (1921, 1922, 1926).

1933 was Ruth’s 20th season in major league baseball. He batted only .301 with 34 home runs, though he still led both leagues in walks. One of the season’s highlights was the inaugural All-Star Game, played at Comiskey Park in Chicago. Ruth hit the game’s first home run. He also robbed Chick Hafey of a home run in the eighth inning, to preserve the AL’s 4-2 win.

The Yankees finished seven games behind the Senators and, in an effort to boost attendance for the last home game of the year, announced that Ruth would pitch against the Red Sox. The 39-year-old outfielder held the Red Sox without a run for five innings. With a 6-0 lead, he stumbled in the sixth, allowing a walk, five singles, and four runs. The Yankees held on to win, 6-5. Although Ruth prepared for the start by throwing batting practice for weeks, the complete game took its toll. He couldn’t so much as comb his hair with his left arm for about a week.49

Ruth took a $17,000 pay cut in 1934. His $35,000 contract was still the highest in the game, but it was his lowest salary since 1921. On July 13, in Detroit, Babe hit his 700th career home run. (At that point, only two players had hit even 300 home runs: Lou Gehrig (314) and Rogers Hornsby (301).) Four days later, Ruth drew his 2,000th walk.

In August, during the Yankees’ final trip to Fenway, a record crowd of 48,000 turned out on a Sunday afternoon, assuming it would be Ruth’s last appearance in Boston. The fans cheered everything Ruth did. When he grounded out in his final at-bat, he was given a long, standing ovation. “Do you know that some of them cried when I left the field?” Ruth said afterwards. “And if you wanna know the truth, I cried too.”50

On the other hand, on September 24, for what was rumored to be his final home game in a Yankees uniform, only 2,000 fans showed up. Babe played only one inning, being replaced by a pinch-runner after drawing a walk. He ended the year with a .288 batting average.

During the off-season, Ruth agreed to travel with an all-star team to Japan. In arranging for a passport, he discovered that his date of birth was February 6, 1895. He had always believed he was born on February 7, 1894.51 He was actually a year younger than he had thought.

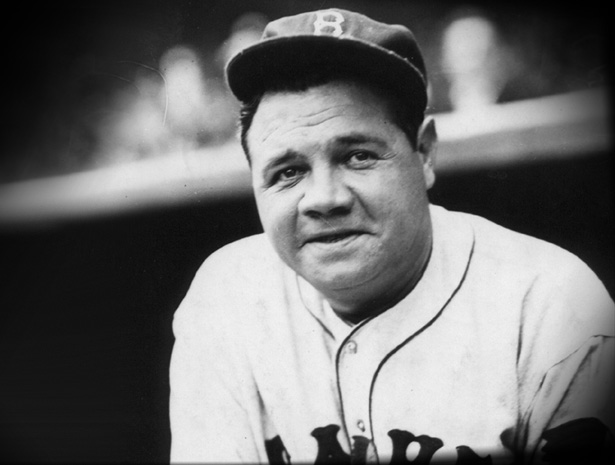

Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert, not wanting Ruth to return in any capacity in 1935, worked out a secret deal with Boston Braves owner Emil Fuchs. Fuchs would offer Ruth a contract that included the titles of “assistant manager” and “vice president.”52 Ruth loved the idea and when he informed Ruppert, the Yankee owner said he wouldn’t stand in Ruth’s way. At spring training in 1935, Ruth learned that the Yankees had already assigned his #3 to George Selkirk. They were also using his locker to store firewood.53

Ruth ended up playing in 28 games for the Braves, batting .181. The one bright spot came on May 25 in Pittsburgh. Ruth belted the final three home runs of his career, and drove in six runs. Career home run #714 disappeared over the right field roof — the longest home run ever hit at Forbes Field.

Ruth ended up playing in 28 games for the Braves, batting .181. The one bright spot came on May 25 in Pittsburgh. Ruth belted the final three home runs of his career, and drove in six runs. Career home run #714 disappeared over the right field roof — the longest home run ever hit at Forbes Field.

Many of the hitting records Ruth once held have been broken, but what cements Babe’s status as the best to ever play the game is the combination of hitting for average, hitting with power, and his work on the mound. In addition to his batting exploits, Ruth also pitched in 163 games, with a record of 94-46 and a career ERA of 2.28 (12th-best in the modern era, since 1900). For 71 years, he was also the unlikely answer to a great trivia question: Who is the only major leaguer to pitch in at least 10 seasons and have a winning record in all of them? Ruth had winning records in 10 seasons: 1914-1921, 1930 and 1933. Andy Pettitte now holds the record at 13 seasons (1995-2007).

After a brief stint as a Brooklyn Dodgers coach, Ruth retired to a life of golf, fishing, bowling, and public appearances. In November 1946, he checked into French Hospital on 29th Street in Manhattan, complaining of headaches and pain above his left eye. It was cancer, though the newspapers never printed the word.

Babe Ruth Day was held at Yankee Stadium (and every other major league park) the following April. A crowd of 58,339 was there and many of them, players as well as fans, were shocked at how frail and shrunken the mighty Babe had become.

Ruth was in and out of the hospital for the next year. He returned to the Bronx one more time, on June 13, 1948, a rainy, cold day. Yankee Stadium was celebrating its 25th anniversary and Babe’s #3 was being retired. Ruth was back in the hospital 11 days later. The cancer had spread to his liver, lungs, and kidneys. He knew he was dying.

Babe Ruth died at 8:01 p.m. on August 16, 1948. He was 53 years old. He is buried at the Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Valhalla, New York, next to his second wife Claire, who died in 1976.

Leigh Montville, author of The Big Bam, called Ruth “the patron saint of American possibility … The fascination with his career and life continues. He is a bombastic, sloppy hero from our bombastic sloppy history, origins undetermined, a folk tale of American success.”54

The New York Times began its obituary: “Probably nowhere in all the imaginative field of fiction could one find a career more dramatic and bizarre than that portrayed in real life by George Herman Ruth.”55

Photo credits

National Baseball Hall of Fame Library

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

Druscilla Null, “‘My Father Was of German Extraction’: Babe Ruth’s Ruth/Rüdt Ancestors,” Maryland Genealogical Society Journal, December 2017. This article documents that Babe Ruth’s great-grandfather was Jacob Ruth/Rüdt of Mondfeld, Germany, whose son, John Anton Ruth, was Babe Ruth’s grandfather.

Notes

1 Allan Wood, Babe Ruth and the 1918 Red Sox (San Jose, California: Writers Club Press, 2001), 55.

2 Ibid.

3 George Herman Ruth, Babe Ruth’s Own Book of Baseball (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1928; Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, Bison Books, 1992), 5-6.

4 Paul W. Eaton, Sporting Life, August 7, 1915.

5 “Talking It Over In The Dugout At Fenway Park,” Boston Post, August 15, 1915.

6 The Boston Globe of June 12, 1916 reported: “Some one of these days Babe Ruth may become an outfielder. [Manager Bill] Carrigan, [pitcher Vean] Gregg and others think that with the proper training, the Baltimore slugger should make a whale of a player for the outer garden.” The next day, the Boston American reported, “Babe is such a great hitter that Bill wants to have him in the lineup daily if possible. So fans at home don’t be a bit surprised if Ruth soon becomes one of the Red Sox outfielders.” Paul Shannon wrote in the Boston Herald, “[If] the batting of certain parties does not improve, big Babe Ruth may soon be a fixture in the Boston outfield.” As quoted in Kerry Keene, Raymond Sinibaldi and David Hickey. The Babe in Red Stockings: An In-Depth Chronicle of Babe Ruth with the Boston Red Sox 1914-1919 (Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1997), 81.

7 Burt Whitman, “Frazee Rejects $100,000 Offer For Pitcher Ruth,” Boston Herald and Journal, April 30, 1918.

8 “Frazee States Col. Ruppert Offered $150,000 For Ruth,” Boston Herald and Journal, May 29, 1918. Frazee: “I think the New York man showed good judgment in making such a big offer. Ruth already is mighty popular in New York, and just think what he would mean to the Yankees if he were playing for them every day and hitting those long ones at the left field bleachers and the right field grandstand!”

9 Glenn Stout, The Selling of the Babe: The Deal That Changed Baseball and Created a Legend (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2016), 52.

10 Wood, 144, 146-147.

12 Wood, 204-206. Several players had both pitched and played in the field before Ruth, but none of them were as talented or successful. Guy Hecker pitched, played the outfield, and spent time at first base from 1882-90. In 1884, he won 52 games for the Louisville Colonels (American Association) and had a 1.80 ERA. Hecker was rarely among the league’s top hitters, but his .341 average in 1886 won the batting title. Washington Senators pitcher Al Orth pulled double duty for several seasons, but when he led the American League in wins and complete games in 1906, he played only one game in the outfield. Doc White of the Chicago White Sox led the American League in 1907 with 27 wins, but appeared on the mound in all but two of his 48 games. In 1909, when he truly divided his time, he batted only .234 (although his on-base average was .347) and was 11-9 with a 1.72 ERA. Doc Crandall played second base and pitched for the St. Louis Terriers of the Federal League in 1914, leading his team in batting average (.309) and tying for the lead in wins (13). The following year, as a pitcher and pinch-hitter, Crandall won 21 games and batted .284.

13 Robert W. Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes To Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1974), 177.

14 Interviews with Allan Wood, July 22, 1995, October 30, 1995, and January 5, 1997. Allan Wood, “Someone Can Recall Red Sox Title,” Baseball America, March 6, 1997.

15 Fred Tenney and Hugh Duffy, former members of the Boston Beaneaters (National League), supported the deal. Tenney: “I agree with Frazee for he knows his business best. … No ball player is indispensable to a team.” Duffy: “Star players do not make a winning team. Players of ordinary ability working for the interest of the club are greater factors in the winning machine than the individual.” Johnny Keenan, leader of Boston’s Royal Rooters: “It will be impossible to replace the strength Ruth gave to the Red Sox. The Batterer is a wonderful player and the fact that he loves the game and plays with his all to win makes him a tremendous asset to a club.” (New York Times, January 7, 1920: 22.) Orville Dennison, a fan living in Cambridge, wrote to the Boston Globe: “Many sane followers of baseball claim that there is no player in the game who is worth paying $100,000 for, and that if the Boston club obtained such a sum, it is the gainer.” (Wood, 352.) Frazee: “[B]aseball fans pay to see games won and championships achieved. They soon tire of circus attractions. And this is just what Ruth has become.” (Stout, 190.) Ed Cunningham of the Boston Herald noted that while Ruth “is of a class of ball players that flashes across the firmament once in a great while … Stars generally are temperamental. This goes for baseball and the stage. They often have to be handled with kid gloves. Frazee has carefully considered the Ruth angle … Boston fans undoubtedly will be up in arms but they should reserve judgment until they see how it works out.” Ed Cunningham, “Red Sox Sell Babe Ruth to Yanks for More than $100,000,” Boston Herald, January 6, 1920: 18.

16 “Babe Ruth Accepts Terms Of Yankees,” New York Times, January 7, 1920: 22.

17 Wood, 352.

18 Kal Wagenheim, Babe Ruth: His Life and Legend (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974), 62.

19 Leigh Montville, The Big Bam: The Life and Times of Babe Ruth (New York: Doubleday, 2006), 111.

20. During the 1946 World Series, Ruth watched the St. Louis Cardinals employ a drastic shift against Ted Williams of the Boston Red Sox. Ruth told sportswriter Frank Graham: “They did that to me in the American League one year. I could have hit .600 that year slicing singles to left.” Mark Gallagher, The Yankee Encyclopedia (6th Edition) (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2003), 206.

21 Montville, 114.

22 Variety, September 24, 1920.

23 Marshall Smelser, The Life That Ruth Built (New York: Random House, 1975), 201.

24 Ruth’s fielding statistics can be found at Baseball Reference (https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/r/ruthba01.shtml#all_standard_fielding).

25 Tom Meany, Babe Ruth: The Big Moments of the Big Fellow (New York: A.S. Barnes and Company, 1947), 84.

26 Montville, 167-71.

27 Montville, 159-60.

28 Paul Dickson, The New Dickson Baseball Dictionary (New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1999), 424.

29 Glenn Stout and Richard A. Johnson. Yankees Century: 100 Years of New York Yankees Baseball (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2002), 99.

30 Hugh Fullerton, “Why Babe Ruth is Greatest Home Run Hitter,” Popular Science Monthly, October 1921. (The magazine’s cover promised: “Babe Ruth’s Home Run Secrets Solved by Science.”)

31 Creamer, 258.

32 Creamer, 261.

33 Creamer, 262.

34 Montville, 203.

35 Wagenheim, 140. The caption read: “Notice how snugly they nestle in the vast cavern of his interior.”

36 Montville, 203.

37 Stout and Johnson, 112.

38 Wagenheim, 140.

39 Montville, 216-18.

40 Montville, 218-21.

41 Creamer, 301.

42 Montville, 282-84.

43 Wagenheim, 196.

44 Montville, 293.

45 Creamer, 364, 367-68.

46 Stout and Johnson, 153.

47 Creamer, 366-67.

48 Creamer, 368. In The Big Bam, Leigh Montville writes: “He called shots all the time. He loved to create situations. It was for other people to determine what they meant. … He challenged his entire environment. Whipped up all parties, then made them shut up. The specifics might be hazy, but the general story was not wrong.” (312) The next day, Cubs starter Guy Bush, facing Ruth in the top of first inning, with men on first and second and no outs, drilled the Babe with a first-pitch fastball. Montville adds: “Something out of the ordinary [had] happened.” (313)

49 Montville, 322.

50 Montville, 327.

51 Ibid.

52 Montville, 337-38.

53 Montville, 339.

54 Montville, 13.

55 Murray Schumach, “Babe Ruth, Baseball’s Greatest Star and Idol of Children, Had a Career Both Dramatic and Bizarre,” New York Times, August 17, 1948: 14. “A creation of the times, he seemed to embody all the qualities that a sport-loving nation demanded of its outstanding hero. … Ruth [was] a figure unprecedented in American life. A born showman off the field and a marvelous performer on it, he had an amazing flair for doing the spectacular at the most dramatic moment.”

Full Name

George Herman Ruth

Born

February 6, 1895 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

Died

August 16, 1948 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.