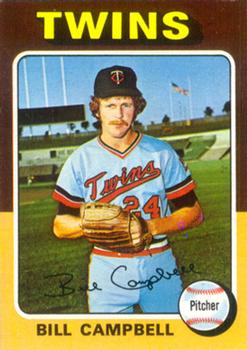

Bill Campbell

Saves became an official major-league statistic in 1969. By the mid-1970s, closers had become firmly entrenched on big-league rosters. Pitchers such as Rollie Fingers, Bruce Sutter, Sparky Lyle, and Rich “Goose” Gossage were helping to define the role, often pitching multiple innings at the end of games. In 1976, the antacid maker Rolaids, whose motto was “R-O-L-A-I-D-S Spells Relief,” created a new award to recognize the outstanding relief pitcher in each league. Because these relievers were also known as “firemen,” winners of the Rolaids award received a trophy with a fireman’s helmet. (The award is now called the Mariano Rivera Award in the American League and the Trevor Hoffman Award in the National League.)

Saves became an official major-league statistic in 1969. By the mid-1970s, closers had become firmly entrenched on big-league rosters. Pitchers such as Rollie Fingers, Bruce Sutter, Sparky Lyle, and Rich “Goose” Gossage were helping to define the role, often pitching multiple innings at the end of games. In 1976, the antacid maker Rolaids, whose motto was “R-O-L-A-I-D-S Spells Relief,” created a new award to recognize the outstanding relief pitcher in each league. Because these relievers were also known as “firemen,” winners of the Rolaids award received a trophy with a fireman’s helmet. (The award is now called the Mariano Rivera Award in the American League and the Trevor Hoffman Award in the National League.)

The first winner of the AL Rolaids Relief Award was Minnesota Twins closer Bill Campbell. The following year, Campbell became the first back-to-back winner of the award while pitching for the Boston Red Sox. Although an arm injury prevented him from sustaining his career at a high level, for a few seasons in the mid-1970s Bill Campbell was one of the most reliable closers in baseball. Campbell then leveraged that success into becoming one of the first ballplayers to take advantage of free agency.

William Richard Campbell was born in Highland Park, Michigan, on August 9, 1948, to Bill and Dorothy Campbell. His father served in the armed forces, per the 1950 U.S. census, which showed the family in North Carolina. When Bill was 10 years old, his father got a new job and moved the family to Pomona, California. On his first Christmas after the move, Campbell remembers receiving a bicycle as a present and going outside in shorts and t-shirt to ride the bike, a contrast to the weather he had been used to previously in Michigan. As a child, Campbell idolized Willie Mays and was a San Francisco Giants fan, even though he lived in Southern California. After graduating from Ganesha High School, Campbell went to Mount San Antonio College in Walnut, California. Campbell had been an outfielder and third baseman before he started pitching full-time while in junior college. His pitching coach at junior college taught Campbell to throw a screwball.1

After playing baseball for two years at Mount San Antonio, Campbell was recruited to play for Cal Poly Pomona, whose coach arranged for Campbell to play summer baseball in Saskatchewan. However, during the process of transferring to Cal Poly, Campbell lost his college deferment and was drafted into the army in 1967. It was the height of the Vietnam War and Campbell joined the 101st Airborne Division.2

Even before he shipped out to Vietnam, Campbell had come to believe that the war was “senseless” when his best friend was killed in action. Stationed stateside and on active duty, Campbell found that the only way he could attend his friend’s funeral was to serve as a military escort for his casket, which he did.3

Campbell remembered exactly how long he had served in Vietnam – “11 months and 27 days” – and said that his two most vivid memories of his military service were arriving in Vietnam and leaving. “I’ll never forget going there,” Campbell recalled years later. “You get off the plane. It’s hot.” He called the day he arrived one of the lowest days of his life. Campbell was trained as a radio and teletype operator and was later promoted to sergeant. He said the first few months of his service were relatively easy, because he remained at base camp as a general’s aide. After a personal conflict with a young officer, Campbell was transferred and found himself on jungle patrols.4

Returning to the States, according to Campbell, was one of the happiest moments of his life. He remembers the plane ride out of Vietnam was eerily silent – everyone was relieved to have survived his tour of duty and to be heading home. As with most soldiers, combat affected Campbell. “You’re not used to seeing people blown up,” he remembered. “When you see it a lot, it changes you.” Campbell gained the distinction of being one of the few major-league baseball players to have served in the military in Vietnam. Others include Jim Bibby, Al Bumbry, and Garry Maddox.5

Campbell served one more year in the military stateside. After his discharge from the Army, he began playing semipro baseball in Long Beach, California with a Dodgers rookie team. In 1971, Campbell threw a no-hitter against the Twins rookie team, which caught the attention of Twins scout Jesse Flores, who then brought Rick Dempsey, a catcher in the Twins farm system, to California for a private throwing session with Campbell. Afterwards, Flores was impressed enough to sign Campbell as an amateur free agent. “I signed at a Denny’s restaurant, over a cheeseburger and a malt,” Campbell remembered. “They signed me for $1,000. I’ll tell you, I thought that was the most money in the world. I couldn’t sleep that night.”6

The 6-foot-3, 185-pound right-hander worked his way up the Twins minor-league system as a starting pitcher who relied on a fastball and screwball. The screwball made him especially tough on left-handed hitters. In 1972, Campbell compiled a 13-10 record with a 2.42 ERA for the Double-A Charlotte Hornets, earning him Southern League Pitcher of the Year honors. He began the 1973 season with the Triple-A Tacoma Twins and went 10-5 before a midseason call-up by the Twins.

He made his major-league debut on July 14, 1973, in a home game against the Indians. Campbell relieved starter Jim Kaat and threw a scoreless ninth inning, giving up one hit and striking out two in a losing effort. His first strikeout at the top level was Chris Chambliss. Although Campbell would start two games in his first season with the Twins, manager Frank Quilici believed that he did not have enough pitches in his repertoire to remain a starter and converted Campbell into a relief pitcher. Once he got used to preparing for games as a reliever and made sure not to leave everything he had in the bullpen, Campbell ended up enjoying relief pitching because he was able to get into more games than he would as a starting pitcher. He appeared in 28 games in 1973, posting a 3-3 record with a 3.14 ERA and seven saves. As a player, Campbell picked up the nickname “Soup” for the obvious connection with Campbell’s Soup.7

He enjoyed his time in Minnesota, calling it “a great place to begin your career.”8 Over the next two years, Campbell posted solid numbers for a mediocre Twins team. He won eight games and notched 19 saves in 1974. Campbell arrived at the 1975 Twins spring training camp with a neatly trimmed beard, which was against team regulations. Team owner Calvin Griffith had loosened the rule to allow mustaches, but beards were still prohibited. Quilici ordered Campbell to shave and the reliever refused, sitting out two exhibition games while waiting for word from players’ union head Marvin Miller. After two days, Miller informed Campbell that he would have to abide by team policy.9 That season, Campbell got only five saves in 47 appearances. Tom Burgmeier was the team’s closer. Campbell actually started seven games that season, including a five-hit, complete-game shutout in the first game of a Fourth of July doubleheader. “I liked relieving better,” Campbell said.10 Indeed, every one of his remaining career appearances came out of the bullpen.

Gene Mauch became Minnesota’s manager in 1976 and named Campbell his closer; Burgmeier became the setup man. Together they formed what The Sporting News called “the top Bicentennial Bullpen.”11 Campbell had spent the winter of 1975-76 pitching winter ball in Venezuela. When he called his parents back home in the States, they told him that his contract had arrived in the mail. Campbell told them to cross out the amount and send it back to the Twins. Campbell had made $22,000 in 1975 and wanted a raise to $30,000. The notoriously tight-fisted Griffith was offering the reliever $27,500. The haggling over his contract made Campbell determined to test the newly created free-agent market at the end of the 1976 season.12

The 1976 season proved to be Campbell’s breakout year and arguably his best season in the majors. He led the league in winning percentage (17-5, .773), games (78), and finishes (68). His 17 wins tied him for second place for most wins in a season for a reliever. Roy Face had 18 in 1959 and John Hiller had 17 in 1974. No one has had more than 16 since – and of interest, that was Tom Johnson, who stepped into Campbell’s role with Minnesota in 1977.

The reliever had taken a risk, but his timing was perfect. “Calvin could have had me for thirty thousand at the beginning of the season,” Campbell said at the time, “but once I picked up a quick five or six saves, he could have saved his breath.” As his season progressed, Campbell proudly noted that he was “building negotiating power as I went along.”13

Campbell also finished seventh in Cy Young Award voting and eighth in MVP voting. As noted, he won the newly created AL Rolaids Relief Pitching Award for best reliever. As with so many relievers of that era, Campbell averaged more than two innings a game, often coming in to pitch in the seventh inning. This helped boost his win totals. Campbell pitched 167 2/3 innings that year, an incredible statistic for a reliever. Obviously, Mauch relied heavily on Campbell that year. In those days, teams carried fewer relievers and there was less player specialization. Reflecting a different set of priorities towards pitchers, Mauch believed that Campbell was strong enough to shoulder the heavy workload, saying that he was “going to use him whenever I need him, unless he tells me he can’t pitch.” Reflecting his competitive spirit, Campbell said that to Mauch only once that season.14 Campbell viewed his nearly 168 innings that year as a point of pride. In later years, many people told Campbell that they couldn’t believe he could rack up that many innings without starting a single game.15

Campbell held out the possibility that he would re-sign with the Twins but was determined to test the open market. “As long as I’ve gone this far, I might as well go all the way,” he said at the end of the 1976 season. “I don’t know what I can get on the open market, and it won’t hurt me to find out what the highest bid is.” Campbell did give the team’s fans some glimmer of hope that “if the Twins come close to matching” the highest bid for him, “I’ll sign with Minnesota.”16

On November 4, 1976, at New York City’s Plaza Hotel, major-league baseball held its first “re-entry draft.” Twenty-four players had played out their options that season and were declared free agents. Among the players were some of the biggest names in the game, including Reggie Jackson, Bobby Grich, Sal Bando, Don Baylor, Rollie Fingers, and Joe Rudi. Bill Campbell was one of the 24. Teams would select players in the “draft.” Players could be selected by as many as 13 clubs, including their current team. Those teams would then have the right to negotiate with their “drafted” players for a free-agent deal.17

That night, Campbell and his agent, Larue Harcourt, went to the bar at the Plaza Hotel. Oakland A’s owner Charlie Finley called the two over to his table. He offered Campbell a three-year $100,000 contract with a $100,000 signing bonus if he signed before he left the table. Campbell and Harcourt had already settled on a figure of a million-dollar contract. “Finley started laughing,” Campbell told reporter Leigh Montville. “He said: ‘A million dollars! You know what? Those dumb s.o.b.’s will give it to you.”18

Two days later, Campbell signed the first free-agent contract of the off-season with the Boston Red Sox. Initially, it looked as if Campbell would sign with the St. Louis Cardinals, but in the end the Red Sox came in with a five-year, one-million-dollar contract.19 The deal made Campbell the third free agent in baseball history after Andy Messersmith and Catfish Hunter.20

Campbell ultimately enjoyed playing for the Red Sox, but got off to a rough start in 1977, compiling a 0-3 record with no saves and a 10.57 ERA by April 25. Campbell felt pressure to live up to his contract, which even he called “ridiculous.” He was a “millionaire” – although his contract was spread out over five years. Still, Red Sox fans were angry that Campbell did not seem to be living up to his new contract. The contrast between the intense Red Sox fans and the more laid-back Twins fans to whom Campbell had been accustomed quickly became apparent. During one April game at Fenway Park, a large sign – “Sell Campbell, Bring Back $1.50 Bleachers” – was hung from the center field wall. “I had the feeling I had to strike everyone out,” Campbell remembered. “If I was going to be making so much more money, I felt I had to be so much better.”21 Fans threw things at him while he was warming up in the bullpen and one fan tossed a beer at this wife in the stands. “It was brutal,” Campbell remembers. He was pressing too much. “It took me a while just to forget the money,” Campbell said. “To just go out there and pitch.”22

Thankfully, he fixed a mechanical flaw in his delivery and turned his season around. He ended the 1977 season with a team-high 13 wins and 31 saves – the latter figure also led the AL – and a 2.96 ERA. He won the Rolaids Relief Award for the second straight year. Red Sox manager Don Zimmer relied heavily on Campbell that year as the Red Sox won 97 games, finishing second to the Yankees in the AL East. Campbell pitched 140 innings in 1977, averaging two innings a game. Later in the season, the fan who hung the banner critical of Campbell called the reliever to apologize. Campbell invited the fan to breakfast and the fan gave Campbell the banner.23

Racking up over 300 innings in two seasons took a toll on Campbell’s arm. He began to feel pain in his shoulder at the end of the 1977 season; by spring training in 1978, his arm troubles were limiting his ability to pitch competitively. Campbell pitched just 50 innings in 29 games in 1978, but still won seven games and earned four saves while battling arm trouble all season. Not having Campbell as a reliable closer hurt the Red Sox, whose 14-game lead over the Yankees in July evaporated. Boston was forced to use a bullpen by committee of Campbell, Bob Stanley, Dick Drago, and Campbell’s former Twins teammate Tom Burgmeier. 24

At the end of the 1978 season, Campbell generated headlines when he said that his former teammate and soon-to-be free agent, Twins first baseman Rod Carew, would probably not sign with the Red Sox. “Boston is not a racially suitable city,” Campbell explained.25 Boston had been dealing for years with the controversy over busing and desegregation in its public schools, an issue that laid bare long-simmering racial tensions in the city. African-American athletes such as Celtics star Bill Russell and Red Sox outfielder Reggie Smith both complained about the racial discrimination they encountered while playing in Boston. The Red Sox had been the last major-league baseball team to integrate, more than a decade after the arrival of Jackie Robinson. Campbell went on to note that if Red Sox outfielder Fred Lynn had had the MVP season that teammate Jim Rice had in 1978, “the man would have been put on a pedestal and taken through Kenmore Square.”26 The implication was that Boston fans did not appreciate the accomplishments of the team’s African-American star outfielder. Campbell lived in the same condo complex as Rice and the two were friends.27

In 1979, Campbell continued to struggle with elbow and shoulder problems. He refused to get surgery and continued to play through his injury. He was no longer the Red Sox closer and was mostly used in a situational role to get out lefthanders.28 The common procedure in these cases was for pitchers to rest their arms and it was not until 1980 that Campbell began to seriously rehab his arm and shoulder. He began the 1980 season on the disabled list and began long-term physical therapy at Boston’s Children’s Hospital. Campbell did not return to the Red Sox until late June.29 When he returned, Campbell was no longer a closer; he was a diminished pitcher with a 4.79 ERA, though he won four games without picking up a save. In the strike-shortened 1981 season, however, Campbell’s fastball was back in the low 90s. Although he pitched in only 30 games, he earned seven saves as the Red Sox used a bullpen by committee with Burgmeier, Campbell, and Mark Clear.30 In his final three seasons with the Red Sox, Campbell never threw more than 54 innings in a season.

As Campbell’s five-year contract was set to expire, the reliever’s relationship with the Red Sox seemed to deteriorate. Considering the impact of his arm injury, the team would offer Campbell only a one-year contract to prove that he could pitch again at his peak level of the mid-1970s. Campbell, though, wanted the security of another long-term contract. “We think we have better pitchers than Bill Campbell,” Red Sox GM Haywood Sullivan said. “I had the feeling I wasn’t wanted,” Campbell said.31

Campbell again made the right call in rejecting a short-term deal with the Sox. He was being courted by the Brewers and A’s, but at the December 1981 winter meetings he ended up signing a three-year, $1.2 million contract with the Chicago Cubs. Cubs GM Dallas Green phoned Campbell when trying to decide whether to offer him a contract. “The one thing that really turned my head was the class guy I was talking to on the other end of the phone,” Green said. “I’m a nut on innards and this man has them.” Green then offered Campbell a contract, beating out the Brewers in the competition for Campbell’s services.32

Campbell began the 1982 season as the Cubs closer, but when he saw the young Lee Smith pitch, he wondered why he had been signed. Campbell realized that his days as the team’s closer were numbered. Smith would take over that role in 1982 on his way to a Hall of Fame career.33 Sliding into a middle-relief role, Campbell remained healthy in his two seasons with the Cubs. He appeared in 62 games and pitched 100 innings in 1982, still getting eight saves. In 1983, he led the NL in pitching appearances with 82. Campbell threw 122 innings and notched another eight saves as Smith led the league with 29 saves and earned a trip to the All-Star Game. Campbell’s arm injuries had taken velocity off his fastball. “I never had the consistency that I had before,” he later recalled. “I had to learn how to do different things . . . I didn’t have the extra stuff, but I actually learned how to pitch better.”34

Before the start of the 1984 season, Campbell was traded to the Phillies along with Mike Diaz for Gary Matthews, Bob Dernier, and Porfi Altamirano. Cubs manager Jim Frey regretted losing Campbell. “I’ll be frank with you, I hated like hell to give up Bill Campbell,” Frey told reporters. “There aren’t many classier people in the game than Campbell.”35 Yet it was a lopsided trade that was not very popular in the Phillies clubhouse. Bill Buckner was supposed to come over with Campbell in the trade, but the Phillies balked at his demands, and he refused to be traded. The Phillies, desperate for relief help, went ahead with the deal for Campbell with the same players.36

By then a 36-year-old pitcher with a diminished fastball, Campbell again served as a middle reliever for the Phillies in 1984. He went 6-5 with a 3.43 ERA in 57 games but failed to pick up a save in seven out of eight opportunities.37 Philadelphia Daily News writer Bill Conlin dubbed Campbell “the Phils’ underachiever No. 1 this season.”38

So the reliever found himself on the move again before the start of the 1985 season as the Phillies traded him and infielder Iván de Jesús to the Cardinals for fellow reliever Dave Rucker. That year, Campbell had a solid season in middle relief (5-3, 3.50 ERA, four saves in 50 games), but the real high point was his first appearance in the postseason. In the NLCS, Campbell pitched 2 1/3 scoreless innings in relief. He added four innings over three games in the World Series against the Royals, who defeated the Cardinals. Campbell was mostly used in a mop-up role – but appearing in the World Series was a career highlight for him.39

Coming off a decent season with the Cardinals in 1985, the 37-year-old Campbell signed a one-year, $200,000 deal with the Detroit Tigers. It was the only offer he received. “To tell you the truth,” Campbell said, “I was really upset that I got only one offer this spring.” Age and past injuries had hurt his market value, but the reliever also believed – rightly, as later upheld in arbitration – that the owners were conspiring to restrict free agency.40 Tigers GM Bill Lajoie wanted to use Campbell in long relief to help reduce the innings burden of the team’s closer, Willie Hernández. Lajoie said Campbell was an attractive option because of his screwball (which was also Hernández’s out pitch), the fact that he had not pitched in the American League for four years, and because “he’s a man of exceptional character.”41

Campbell suffered through the 1986 season with a bone spur in his elbow, which landed him on the disabled list a number of times.42 He still managed to appear in 34 games in 1986, but at the end of the season, the Tigers released him.

During the 1987 spring training, Campbell drove down to Florida and “knocked on doors” hoping to find a team that would sign him. Montreal Expos manager Buck Rodgers finally agreed to make him a non-roster invitee. Campbell made the club at the close of training camp.43 Although he pitched well enough to make the team, he gave up 12 earned runs in 10 innings to start the season and was released by the Expos on May 1. At 38, his big-league career was over. He had pitched 15 seasons for seven different teams and compiled an 83-68 record with 126 saves and an ERA of 3.54.

Upon his retirement, Campbell took a marketing job working on commission.44 He played amateur baseball in the Chicago area, “drinking beer in the parking lot after the games.”45

Yet Campbell had serious off-field burdens. His agent, Larue Harcourt, was a man who rode the new era of big free-agent paydays for his clients – but also symbolized the darker side of the business. Many of his clients were not financially sophisticated and allowed Harcourt to invest their money in shady deals that the players never understood – and about which Harcourt provided them little information. Besides Campbell, other Harcourt clients included Don Sutton, Rick Wise, Doug Rau, and Ken Reitz. Journalist Armen Keteyian estimated that Harcourt lost 14 of his clients some $6 million by 1987. To make matters worse, Harcourt set up suspect tax shelters for his clients. Not only did the ballplayers lose money in their investments with Harcourt, but the IRS came down hard on them and demanded back taxes with penalties. Campbell estimated that he lost $800,000 in his investments with Harcourt, and he had to pay more to the IRS to settle the back taxes. “I don’t like to get going on the subject,” Campbell told Keteyian. “It ruins my whole day.”46

Amid these financial problems, Campbell received a call from his former Red Sox teammate Bill Lee, who told him about the newly created Senior Professional Baseball Association. In the inaugural 1989 season of the new league, Campbell joined the Winter Haven Super Sox, where he led the league with a 2.12 ERA in 72 innings. The following year, Campbell pitched for the Sun City Rays in Arizona, before the entire league folded one month into its second season.47

Playing in the SPBA rekindled Campbell’s love of the game. “I realized in Florida how much I missed baseball,” he remembered, “and that’s when I got the bug to get back in.”48 Fred Stanley, who worked in the Milwaukee Brewers organization at the time, was the third base coach for Campbell’s Seniors team and arranged for Campbell to get a get a job with the Brewers.49 In the 1990s, Campbell served for a number of years as a pitching coach in Milwaukee’s minor-league organization. In 1999, he joined the big club as their pitching coach.50 After that one season, Campbell was released. He spent the next three years as a pitching coach in the Cardinals minor-league system, then retired from baseball.51

In retirement, Campbell and his wife Linda made their home in the Chicago area, where Linda is a professor of psychology at Harper College in Palatine, Illinois. The Campbells were married for 46 years and had three children – Emily, Marnie, and Joseph – and four grandchildren.52 Bill Campbell passed away from cancer on January 6, 2023.

Last revised: January 8, 2023

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Author interview with Bill Campbell, February 23, 2022; Chuck Greenwood, “’Soup’ Came in Seven Varieties in 15-year Career,” Sports Collectors Digest, July 16, 1999: 96-97.

2 Author interview with Bill Campbell, February 23, 2022; Drew Olson, “Brewers’ Pitching Coach Served in Vietnam,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, March 17, 1999.

3 Author interview with Bill Campbell, February 23, 2022.

4 Olson, “Brewers’ Pitching Coach Served in Vietnam.”

5 Olson, “Brewers’ Pitching Coach Served in Vietnam.”

6 Bob Ibach, “Cubs Spell Relief Campbell,” Chicago Cubs Scorebook, 1982, 70.

7 Bill Ballew, “Campbell Soup,” Sports Collectors Digest,” April 19, 1996: 70-72; Author interview with Bill Campbell, February 23, 2022.

8 Interview with Bill Campbell, https://twinstrivia.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Campbell.mp3.

9 “The Beard Goes, So Bill Campbell Stays,” Orlando Sentinel Star, March 5, 1975: 7-D.

10 Interview with Bill Campbell, https://twinstrivia.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Campbell.mp3.

11 Bob Fowler, “Campbell Earns Twin ‘Young’ Vote,” The Sporting News, October 9, 1976: 16.

12 Author interview with Bill Campbell, February 23, 2022; Bob Fowler, “Campbell’s Spring Gamble Paid Off in October,” The Sporting News, October 16, 1976: 3.

13 Gerry Finn, “Million Dollars Later,” Springfield Republican, September 11, 1977.

14 Fowler, “Campbell’s Spring Gamble Paid Off in October,”3; Finn, “Million Dollars Later.”

15 Ballew, “Campbell Soup.”

16 Fowler, “Campbell’s Spring Gamble Paid Off in October.”

17 Gregory H. Wolf, “1976 Winter Meetings: Changing Demographics and Broadcast Challenges” in Baseball’s Business: The Winter Meetings, Volume 2, 1958-2016, Steve Weingarden and Bill Nowlin, eds. (Society for American Baseball Research, 2017), 105-112; Murray Chass, “For Sale Today: 24 Baseball Players,” New York Times, November 4, 1976: 64.

18 Leigh Montville, “The First to Be Free,” Sports Illustrated, April 16, 1990, https://vault.si.com/vault/1990/04/16/the-first-to-be-free-in-1976-baseballs-first-free-agents-landed-the-big-big-money-lucky-guys-they-were-set-for-life-or-were-they.

19 There was some confusion initially about the length of Campbell’s contract, as well as the structure of the contract. Most press reports announced that it was a four-year deal. However, the deal would end up being for five years at $200,000 per year.

20 Murray Chass, Red Sox Sign Campbell to 4-Year, $1 Million Pact,” New York Times, November 7, 1976: S3.

21 Montville, “The First to Be Free,” https://vault.si.com/vault/1990/04/16/the-first-to-be-free-in-1976-baseballs-first-free-agents-landed-the-big-big-money-lucky-guys-they-were-set-for-life-or-were-they.

22 Interview with Bill Campbell, https://twinstrivia.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Campbell.mp3.

23 Author interview with Bill Campbell, February 23, 2022; Montville, “The First to Be Free,” https://vault.si.com/vault/1990/04/16/the-first-to-be-free-in-1976-baseballs-first-free-agents-landed-the-big-big-money-lucky-guys-they-were-set-for-life-or-were-they.

24 Larry Whiteside, “Campbell’s Comeback,” Boston Globe, February 25, 1979: 37.

25 “Campbell Says Boston Isn’t Racially Suitable,” Boston Globe, October 24, 1978: 29.

26 “Campbell Says Boston Isn’t Racially Suitable.”

27 Author interview with Bill Campbell, February 23, 2022. For more on Campbell’s comments about race and the Red Sox, see Marc Onigman, “Facing the Race Factor,” Boston Globe, October 27, 1978: 23 and Leigh Montville, “I am a Black Player. . . Do I Come to Boston?” Boston Globe, October 26, 1978: 47. For more background on the history of race and the Red Sox, see Howard Bryant, Shut Out: A Story of Race and Baseball in Boston (New York: Routledge, 2002).

28 Larry Whiteside, “Campbell Right Pick,” Boston Globe, July 23, 1979: 30.

29 Author interview with Bill Campbell, February 23, 2022; Joe Giuliotti, “Security Request Doomed Campbell,” The Sporting News, December 5, 1981: 57.

30 Ibach, “Cubs Spell Relief Campbell.”

31 Giuliotti, “Security Request Doomed Campbell.”

32 Joe Goddard, “A Phone Call Does It; Cubs Sign Campbell,” The Sporting News, January 9, 1982, 42.

33 Author interview with Bill Campbell, February 23, 2022.

34 Ballew, “Campbell Soup.”

35 Peter Pascarelli, “Trading with Phils Hasn’t Solved the Cubs’ Problems,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 8, 1984: G5.

36 Rich Ashburn, “A Tale of Two Trades,” Philadelphia Daily News, November 13, 1984: 85.

37 Peter Pascarelli, “How Phillies Became a Club Fated to Fade,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 16, 1984: E1.

38 Bill Conlin, “Phillies’ Bullpen Bowled Again,” Philadelphia Daily News, September 7, 1984: 120.

39 Greenwood, “’Soup’ Came in Seven Varieties in 15-year Career.”

40 Larry Whiteside, “It Wasn’t a Free-For-All This Time,” Boston Globe, March 12, 1986: 33.

41 Peter Gammons, “Sox Sign Sambito,” Boston Globe, February 1, 1986: 29.

42 Interview with Bill Campbell, https://twinstrivia.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Campbell.mp3.

43 Author interview with Bill Campbell, February 23, 2022; “Expos Sign Another Aging Veteran in Endless Search for Talent,” Ottawa Citizen, March 7, 1987: E3.

44 Greenwood, “’Soup’ Came in Seven Varieties in 15-year Career.”

45 Montville, “The First to Be Free,” https://vault.si.com/vault/1990/04/16/the-first-to-be-free-in-1976-baseballs-first-free-agents-landed-the-big-big-money-lucky-guys-they-were-set-for-life-or-were-they.

46 Armen Keteyian, “At Times You Flat Out Cry: How Larue Harcourt’s Baseball Player Clients Were Driven to Tears,” Sports Illustrated, October 19, 1987, https://vault.si.com/vault/1987/10/19/at-times-you-flat-cry-how-larue-harcourts-baseball-player-clients-were-driven-to-tears; Montville, “The First to Be Free,” https://vault.si.com/vault/1990/04/16/the-first-to-be-free-in-1976-baseballs-first-free-agents-landed-the-big-big-money-lucky-guys-they-were-set-for-life-or-were-they.

47 Author interview with Bill Campbell, February 23, 2022; William Schneider, “Our Last Season in the Sun: The Saga of the Senior Professional Baseball Association,” in Baseball in the Sunshine State, Cecilia M. Tan, ed. (Society for American Baseball Research, 2016), 74-79.

48 Ballew, “Campbell Soup.”

49 Greenwood, “’Soup’ Came in Seven Varieties in 15-year Career.”

50 Greenwood, “’Soup’ Came in Seven Varieties in 15-year Career.”

51 Author interview with Bill Campbell, February 23, 2022.

52 Author interview with Bill Campbell, February 23, 2022; Interview with Bill Campbell, https://twinstrivia.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Campbell.mp3.

Full Name

William Richard Campbell

Born

August 9, 1948 at Highland Park, MI (USA)

Died

January 6, 2023 at , IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.