Dodger Stadium (Los Angeles)

This article was written by Curt Smith

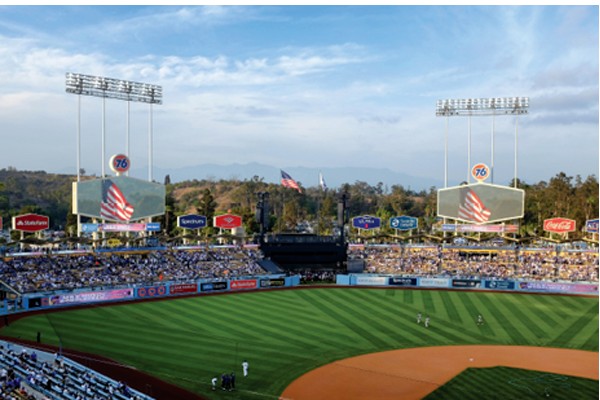

Fans cheer on their favorite team on June 29, 2021, at Dodger Stadium. (Copyright: Steven Cukrov / dreamstime.com)

On October 8, 1957, the stockholders and directors of the Brooklyn Baseball Club announced that the franchise would move to Los Angeles for the 1958 season.1 A welcoming parade jammed downtown LA streets.2 On the steps of City Hall, longtime Dodgers President and owner Walter O’Malley gave Mayor Norris Poulson home plate from Ebbets Field.3 Yet uncertainty lingered: Where would the Dodgers play?

In time, O’Malley forged Dodger Stadium, debuting in 1962 «with perfect sightlines for each of its 56,000 seats and glorious views in all directions,” said noted baseball architect and urban planner Janet Marie Smith. With a nonpareil 16,000 parking spaces, it was “surrounded by Elysian Park, one of the most beautiful urban oases in America – a park within a park.”4 Exuding the charm of baseball’s early-century classic sites, it avoided the later boredom of multi-sport stadiums. Fusing beauty and amenity, baseball’s third-oldest major-league home still is forever young.5

What, though, preceded it? As a stopgap O’Malley considered the longtime Pacific Coast League’s Wrigley Field, acquired by the Brooklyn franchise in February 19576 but housing far too few (20,450)7 for a big-league park. Pasadena’s famed football Rose Bowl (capacity 91,136)8 was too vast for baseball. With time running out, O’Malley chose Los Angeles’s 94,600-seat Memorial Coliseum9 to house his team until a new ballpark could be built.

Opening in 1923, the Coliseum was “a football and track and field place,” said Dodgers 1950-2016 radio/TV legend Vin Scully, “and football and baseball demand different configurations.”10 Left field’s 250-foot foul line, later measured at 251, was the majors’ shortest. To compensate, O’Malley hoisted a 42-by-140-foot screen. Center field’s last bleacher row was 700 feet from the plate,11 Angelenos bringing radios to hear Vin tell them what they couldn’t see. In 1958 the seventh-place club drew 1,845,556, dwarfing Brooklyn’s prior-year 1,028,258.12 It presaged things to come.

Ahead lay “The … Taj O’Malley,”13 in an area of LA to which Walter already had been drawn. In May 1957 he took a helicopter ride to survey possible sites for a new park,14 traveling two miles from downtown over a mélange of “mountains, hills, valleys, and basins.”15 At a gas station O’Malley found on a map the name of a plateau he had found especially striking on “underdeveloped city-owned ground.” It was “surrounded by urbanity – freeways, a teeming population, skyscrapers, sprawl – yet in traveling up a slight but steady palm-tree-lined grade, fans had the immediate illusion, in true movie style, of a park.”16 The site’s name was Chavez Ravine.

O’Malley “liked everything – the access, the vicinity, potential: the freeways above all,” longtime general manager Emil J. “Buzzie” Bavasi said.17 Later in 1957, the Los Angeles City Council voted 10-4 to accept Wrigley Field from the Dodgers, buy 300 acres of Chavez Ravine, and spend $2 million on infrastructure. LA wanted the team. “All O’Malley wanted was land. The city and county of Los Angeles had plenty of that,”18 including Ravine hillside inhabited by “illegal Mexican immigrants.”19 To get it, O’Malley swapped his property in Watts, the site of Wrigley Field.

Aiding him was City Councilwoman Rosalind Wyman, first elected to the Council in 1953 at age 22. Believing that “people wanted sports,”20 she vocally backed the June 3, 1958, “Dodgers Referendum” to let O’Malley buy the acreage. The vote pivoted on a five-hour June 1 KTTV “Dodger Telethon,” starring baseball-loving celebrities including Jack Benny, George Burns, Ronald Reagan, Debbie Reynolds, and Joe E. Brown, chairman of the Taxpayers Committee for “Yes on Baseball.” O’Malley made an eloquent plea, more than two million watching the show days before the vote. It helped the referendum pass, 351,683 to 325,898, a 25,785-vote margin.21

At the time, some wondered what the Dodgers don could possibly see in Chavez Ravine. Squatters’ shacks and grazing goats roamed amid the refuse. From the helicopter O’Malley had seen “dogs, possums, skunks, jackrabbits, gophers, rusty tin cans, rotting tires, moribund mattresses, and broken beer bottles.”22 The squatters included Manuel Arechiga, his wife, and four granddaughters, who were evicted in August 1957, but not before biting and bruising sheriff’s deputies.23 Other residents refused to leave until as late as 1960.24

Trying to block the sale, critics brought countless lawsuits, accusing O’Malley of reaping a giveaway with hidden oil and mineral rights.25 Twice the State Supreme Court ruled in the Dodgers’ favor. On September 17, 1959, groundbreaking ceremonies occurred at the Ravine. The next month the US Supreme Court ditched the protesters’ last appeal. Tractors then began their work. Soon O’Malley began the task of building what he hoped would be the ultimate baseball site.26

On February 18, 1960, O’Malley finalized the sale, paying $494,000 to buy land, then believed to be worth $92,000,27 to be used to build Dodger Stadium. He could afford it, that year’s Dodgers drawing a National League record 2,253,887. Meantime, construction intensified. Fused: 23,000 precast concrete frames and planks. Removed: 8 million cubic yards of earth. Supervised and engineered by: Captain Emil Praeger of Praeger, Kavanagh, and Waterbury, New York. Constructed by: Vinnell Constructors of Alhambra, California.28

Used: 19 giant earth-movers, 80,000 tons of asphalt and paving for parking lots and roads, 546 tons of cast iron, 40,000 cubic yards of concrete, 3 million pounds of reinforced steel, 3 tons of aluminum nuts and bolts, and 375,000 feet of lumber. Employed: Up to 342 workers at peak. Busted: the budget, $23 million, about twice the original estimate. Crucial was O’Malley’s passion to outdo any park ever built – to Scully, the “Golden Gulch”;29 to the public, “Dodger Stadium” or “Chavez Ravine – used interchangeably – involving him at every level.

In the Dodgers’ 1956 tour of Japan, Walter had discovered ground-level suite seating – “dugout boxes” – built by connecting “the roof of the first-base dugout with the roof of the third-base dugout,”30 patrons and players getting the same up-close view. Mentally, O’Malley listed this and other features that he felt the new park should have like Santa Ana Bermuda grass, red infield and warning track clay, and palm trees beyond the outfield. Praeger preferred an 85,000-seat enclosed site with a center-field fountain. O’Malley craved a grand location and scenic park, meriting “enormous credit for declining to enclose the outfield.”31

Instead, Walter approved single-tier bleachers, five-tier seating (a baseball first) just past each line, and perpendicular bullpens to separate the bleachers from foul-line seats. Parking spaces held “cars on 21 terraced lots at five different levels. Seating and parking levels were color-coordinated for fan convenience”32 – top (sky blue), loge (tangerine orange), Stadium Club and dugout box (red, yellow, and blue), reserved (sea foam green), and field (yellow) – each minimizing a need for elevators, escalators, stairs, and lengthy treks after parking.33

Janet Marie Smith has related an “urban legend I believe to be true” about LA’s kinship with its ubiquitous symbol: the car. Chavez Ravine’s Club level – itself a baseball first – had a very wide concourse. Until officials ruled that gasoline-powered autos “would be unsafe inside an occupied stadium,”34 O’Malley hoped Club level members could drive to their seats, cars parked behind them. In 1960 an aerial photo showed “Dodger Stadium beginning to take shape,”35 several decks faintly evident of the first privately financed park since Yankee Stadium opened in 1923.

As Smith, an adviser to the Orioles (Camden Yards), Red Sox (Fenway Park), and Dodgers (since 2012), observed in her essay, “Ballpark Diaries: Notes from the Field,” the “glorious setting, carved into the hillside of Chavez Ravine,” enchants.36 At first glance, it might seem that O’Malley positioned the park to “capitalize on the views of the snowcapped San Gabriel mountains and the green of Elysian Park to the north and the downtown skyline to the south.” In fact, in 1962 “downtown’s only tower was City Hall to the East.”37 The city grew with the team, the ballpark’s third-base line fixed due north on the field to curb interference from the sun.

From any perspective, O’Malley believed in the Dodgers park and his Westward-Ho, claiming history would redeem him. By the end of 1961, the Coliseum had lured 7,974,738 since 1958,38 vindicating the trek from Brooklyn. Jerry Doggett, a 1956-87 Dodgers announcer, recalled how the first time “I came out of the dugout [in 1962] and looked up, I talked with Walter, and he was as pleased as a person could possibly be.”39 Having survived landslides and lawsuits, O’Malley and Rosalind Wyman walked through the Club level the night before 1962’s Opening Day,40 marveling at the result.

The next afternoon, April 10, after a parade passed through Center City, squeaky-clean Dodger Stadium opened with two temporary gaffes: Emil Praeger forgot to include water fountains – ironic given his design – and foul poles were in foul ground. For 1962, the NL ruled them fair. Doggett remarked, “It was almost like the club’s Brooklyn past,”41 crystallized by a 1926 game against the Braves when three Dodgers occupied third base.42 In 1963 the team relocated home plate slightly so that each pole became fair.43 Consequently, the Ravine’s most visible landmark is not foul-ball homers but a 10-story elevator shaft bearing the team’s logo rising behind home plate atop the upper deck.

Most found dimensions fair: lines, 330 feet; alleys, 380 (370 in 1969 and 385 in 1983); left- and right-center, 395; and center, 410 (400 in 1969). The top deck linked first to third base, other decks reaching past the poles. Unique: upturned concrete sunscreen poured in place on the top deck, a zig-zag wavy pavilion roof using folded corrugated metal, and four hexagonal scoreboards: two field-level auxiliary boards, baseball’s largest message/out-of-town board in left, and an in-game information board in right. A 10-foot (8 in 1973) fence tied left- and right-center.44 The 1000 Elysian – Greek for “paradise” – Park Avenue address hailed baseball’s first park, Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey.45

In Brooklyn O’Malley had telecast each home set; in LA, almost none. Since many felt that “here was the finest sports palace ever conceived,”46 they were happy to pay in person. The change profited radio: hence Scully. Atypically, the Ravine opener was locally televised, Vin emceeing the pregame rite. Attendance was 52,564: Trapped in traffic, some gave up and went home. O’Malley’s wife, Kay, tossed out the first ball. Johnny Podres lost, 6-3, to Cincinnati’s Bob Purkey. First hit/run: The Reds’ Eddie Kasko. Homer: mate Wally Post. Dodgers hit: Duke Snider. LA run: Jim Gilliam. “Reds Crash Stadium Party,” wrote the Los Angeles Times.47

Jackie Robinson’s statue stands near the center field entrance at Dodger Stadium. (Jon SooHoo / Los Angeles Dodgers)

When Dodger Stadium opened, it had far more foul turf than now: “as much as multipurpose parks, presumably so a 50-yard line for football would fit,” Smith wrote in another essay, “How the Firsts Have Fared.”48 Architect Edward H. Fickett’s drawings at the University of Southern California even suggested placing “the outfield seating on wheels so it could be moved to alter the center field for football or other uses.”49 Ultimately, O’Malley was wise enough to see the folly of a multisport yard. By 1999, then-owner Fox Entertainment Group even axed the “1962 dugout suites … and minimized foul territory to create a [solely baseball] premium seating area in front of the field box seats.”50

O’Malley Sr. resigned as president in 1970, remaining owner and chairman till his death in 1979. On January 4, 1997, his successor, son Peter, met at the park with Scully, by 1976 fan vote named “most memorable personality” in LA Dodgers history.51 Learning that O’Malley Jr. and sister Terry meant to sell the franchise, Vin felt “a … closure of a major portion of my life.”52 Next year media czar Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. bought the team for $311 million.53 In 2004 Fox sold it to Frank McCourt, who went bankrupt, yielding to Guggenheim Baseball Management LLC in 2012, after which continuity again became a Dodgers rite.

Almost from the start the Ravine became a magnet. “People poured in from all over California, western Canada and northern Mexico, even Hawaii to marvel at the sheer grandeur of the place,” Frank Finch wrote.54 Pitching became a theme; speed, another, as in Dodgers shortstop Maury Wills stealing a record 104 bases in 1962. “It’d been [at Brooklyn] all power,” Wills said. By contrast, now “I’d steal second and … Gilliam sacrificed me to third and I’d come home on an infield out.” Said Mets skipper Casey Stengel: “He’s the most amazin’ slider I ever saw.”55

What has been amazin’ – at least indelible – about Dodger Stadium? In 1962 the ex-Brooks lost a tiebreaking playoff to the Giants but drew a big-league record 2,755,184 against the American League Angels’ 1,144,063 in the latter’s first of four years of tenancy. Sandy Koufax no-hit the Mets. Next year he went 25-5, tossed his second of four no-nos, and won two games in the Dodgers’ World Series sweep of the Yankees. “When Sandy was in top form, I became a fan out there on the field,” said 1962-63 batting titlist Tommy Davis. “You sometimes forgot you’re playing baseball because Sandy’s controlling the whole game.”56

LA took the 1965 Series, enduring Sandy’s next-year retirement from an arthritic elbow: “I don’t regret for one minute the 12 years I’ve spent with baseball, but I could regret one season too many.”57 Koufax finished 165-87, leading the NL thrice in victories (high, 27), four times in strikeouts (best, 382), and five years in ERA (at or below 2.54). The Ravine evokes Don Drysdale, too, Big D copping 1962’s 25-9 Cy Young Award and in 1968 pursuing Walter Johnson’s record for consecutive scoreless innings: 56 in 1913. By May 31, Don had 44 straight. “Curve – hit him!” Vin Scully etched a no-out bases-full ninth-inning pitch to Dick Dietz, the streak ending, or had it? “Hold everything!” – the umpire gesturing “as if to say Dietz stuck his arm in front of the pitch.”

Drysdale escaped the jam, his streak reaching 58⅔ innings, then tore his rotator cuff, retiring in 1969 with a 209-166 record.58 He broadcast for several teams and networks, the last six years with the Dodgers. On July 3, 1993, Don, 56, had a fatal heart attack in Montreal. That night Scully, a close friend, disclosed it during the game: “Never have I been asked to make an announcement that hurts me as much as this one,” Vin said. “And I say it to you as best I can with a broken heart.”59

Dodger Stadium also evokes history – in 1969 Willie Stargell belted the first homer out of the park, estimated at 506 feet 6 inches over the pavilion roof. (He later encored at 470 feet.) Others: Ronald Acuña Jr., Giancarlo Stanton, Mark McGwire, Dodger Mike Piazza, and Fernando Tatis Jr.60 – and heroism. In 1976 two men left the bleachers. One laid the US flag out, spreading lighter fluid. The other lit a second before Cubs outfielder Rick Monday raced to take it “away from him!” exclaimed Scully, a World War II veteran. “That guy was going to set fire to the American flag! … Rick will get an ovation, and properly so. … And now, a lot of the folks are standing. And now the whole ballpark!”61

Chavez Ravine conjures Hollywood. “Forget the glitz,” said longtime vice president of player personnel Al Campanis. “It’s TV-film tradition that matters.” Movie scenes have been filmed at Dodger Stadium. TV in the 1960s lured Dodgers Koufax, Drysdale, and coach Leo Durocher, among others, Big D appearing on The Rifleman and variety shows with Red Skelton, Groucho Marx, and Steve Allen. In a 1963 episode of Mister Ed, a series based on a talking horse, Ed offered hitting advice to Durocher.62 Celebrities like Benny and Cary Grant regularly visited the ballpark,63 as stars like Arsenio Hall, Jennifer Lopez, and Matthew McConaughey did in later years.64

The Ravine includes rites like the best-selling Dodger Dog, the “Peanut Guy” Roger Owens, 1954-76 manager Walter Alston’s “solidity,” and and 1976-96 skipper Tommy Lasorda’s wit: “Baseball is like driving, it’s the one who gets home safely that counts.”65 Scout Mike Brito was another institution, approached by Campanis in 1979 when pitcher Bob Welch began struggling. Al: “What are you doing tonight?” Brito: “Nothing special. Why?” Campanis: “I want you to go down to field level.” Standing behind the plate in a dugout box, Mike used a radar gun to judge pitches. His “The Straw-Hat Man” attire made the cigar-chomping Brito famous.66

Dodger Stadium recalls precedent. In 1967 it braved the ballpark’s first rainout after 737 games.67 The ’78 Angelenos became the first team to draw 3 million or more in attendance.68 In 1980 the Ravine debuted a large screen, high-definition left-field Electric “Diamond Vision Scoreboard” with line score, lineup, and replay; shortly, most of baseball followed. In turn, it was replaced in 2013 by a new state-of-the-art video board.69 In 1984 Dodger Stadium unveiled a star-spangled precedent, hosting part of that year’s Summer Olympics, the first privately financed Games.70

Another first buoyed Opening Day 1981: 20-year-old rookie Fernando Valenzuela, found in 1977 in Mexico by Dodgers scout Corito Varona, hurling a shutout in his first big-league start. “Got him swinging! And a little child shall lead them!” Vin cried. “Fernandomania included arguably baseball’s first Spanish-speaking broadcaster translating English into Spanish for Valenzuela, then back: Ecuador-born Jaime Jarrin arrived in LA in 1955, began play-by-play in 1959, and got the 1998 Hall of Fame Ford C. Frick Award for broadcast excellence, joining Scully and past Dodgers Red Barber and Ernie Harwell. He retired in 2022.71

In time, O’Malley had Scully do TV as well as radio. Other announcers ferried play-by-play, too. After René Cárdenas trained Jarrin, he went to Houston, returning to LA in 1982-96. From 1977 to 2004, Ross Porter shared radio/TV, using statistics like Roy Acuff did a fiddle. In 1989 Vin waived a road trip, Drysdale away. The game finally ended in the 22nd inning, LA winning, 1-0. By then, even statistics looked good. In 2005 Brooklyn native Charley Steiner joined Scully, so wowed by Vin as a child that Mom bought him a right-handed mitt at 6, assuming that her left-handed son’s glove would fit that hand. Steiner, a future five-time Emmy Award winner,72 soon found where his future lay: above the field, not on it.73

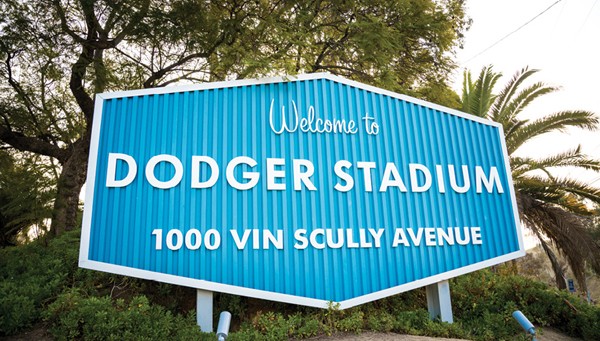

The entrance to Dodger Stadium at 1000 Vin Scully Avenue. (Copyright: Liamwh7 / dreamstime.com)

Dodger Stadium recalls defeat. “Big Blue” (a Dodgers moniker) trailed 1985’s best-of-seven League Championship Series to St. Louis but led Game Six, 5-4, in a one out and two Cardinals on base ninth inning. Lasorda and reliever Tom Niedenfuer communed on the mound, deciding to pitch to Jack Clark, who promptly homered: Redbirds win, 7-5. Later, the Dodgers manager consoled a shattered Niedenfuer, saying, “We wouldn’t be there without your [19 regular-season] saves. … [you] should talk to the media – be a Dodger.”74

The Ravine also evokes victory. An injury to each leg made Kirk Gibson ostensibly unable even to pinch-hit in 1988’s Series opener. In the ninth, A’s up 4-3, Kirk told Lasorda he could hit. Eyeing a monitor, NBC TV’s Scully said, “And look who’s coming up!” Barely able to swing, fouling off pitches, Gibson worked a 3-and-2 count. Then: “High fly ball into right field! She is gone!” Vin glittered, silent another 67 seconds, letting the crowd hold sway. Finally: “In a year that has been so improbable, the impossible has happened!”75 Lasorda, who called the park “Blue Heaven on earth,” levitated.76 Kirk pumped fists like pistons. Next day NBC ran an elegiac feature tying the plot to film’s The Natural – except that by contrast even fiction paled.

Three years earlier lanky right-hand pitcher Orel Hershiser had gone 19-3 in his second full major-league season. Now, in World Series Game Five, up 5-2, he faced Oakland’s Tony Phillips. “Got him!” Scully said of Orel’s second 1988 Classic triumph. “They’ve done it! Like the 1969 Mets, it’s the Impossible Dream revisited!” The previous month Hershiser had lived another dream, forging 59 straight scoreless innings to break Drysdale’s 1968 record.77 Thrice leading the NL in innings, Orel pitched for LA through 1994, spent five years with three other clubs, then returned in 2000 to Chavez Ravine, retiring at age 42 with a 204-150 record.78

In its seventh decade, Dodger Stadium respects age. Don Sutton pitched for Los Angeles in 1966-80 and then for four other teams, returning to the Ravine for a final year in 1988. Retiring at 43, he was, as of his death in 2021, LA’s all-time leader in innings pitched, wins (233), shutouts, and strikeouts.79 (Clayton Kershaw passed him in K’s in 2022.80) By comparison, in 1992, Eric Karros launched the Dodgers’ record of five consecutive Rookies of the Year, preceding Mike Piazza, Raul Mondesi, Hideo Nomo, and Todd Hollandsworth.81 Youth had been served.

Even in a pitching-friendly park, offense can rule. In 2000 Gary Sheffield tied Duke Snider’s then-single-season home-run mark (43): the sole Angeleno to top .300 (.325) with at least 30 homers, 100 runs batted in, 100 walks, and 100 runs for a second straight year.82 LA’s single-season best includes Tommy Davis’s 153 RBIs and 230 hits (both 1962) and Shawn Green’s 49 home runs (2001).83 Career highs include Sheffield’s on-base percentage (.438), slugging percentage (.643), and OPS (1.081).84

Like Koufax, Big D, Hershiser, and Sutton, Kershaw symbolized artistry on the mound: NL 2014 MVP, 2011-13-14 Cy Young Award honoree, thrice league-best in wins, first to lead baseball in ERA four straight years (2011-14), and as Steve Garvey had and Justin Turner would, received the Roberto Clemente Award in 2012 for exemplifying “extraordinary character, community involvement, philanthropy, and positive contributions, both on and off the field”85 – the same kind of service that lets the Los Angeles Dodgers Foundation programs help 2.3 million children each year.86

LADF grants and programs generously support such projects as “Dodgers Dreamfields,” “LA Reads,” and “Dodgers RBI [Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities].”87 Such charity has been contagious. In his 2000-04 Chavez Ravine career, outfield alumnus Green donated $1.5 million to the Dodgers’ Dream Foundation, backed four local Dodgers “Dreamfields,” and broke his 415-consecutive-game streak to honor the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur, not playing on September 5, 2001.88

Dodger Stadium has shared sorrow. On September 11, 2001, four planes were seized by terrorists and crashed into New York City, the Pentagon, and rural Pennsylvania, killing nearly 3,000 Americans. Six days later the Dodgers played their first post-9/11 game, at the Ravine. In a pregame video, President George W. Bush asked the nation to “go back to work.” Scully then spoke: “And so, despite a heavy heart, baseball gets up out of the dirt, brushes itself off, and will follow his command, hoping in some small way to inspire the nation to do the same.”89

Chavez Ravine has known joy. On September 18, 2006, the NL West title at stake, LA trailed San Diego, 9-5, in the ninth inning. Traffic exited while Jeff Kent, J.D. Drew, and Russell Martin then went deep. As cars U-turned, Marlon Anderson homered – a fourth straight homer: 9-all. Scully beamed: “Can you believe this inning? In fact, can you believe this game?” San Diego regained a 10-9 10th-inning edge, whereupon Kenny Lofton walked in the home half and Nomar Garciaparra “hits a high fly ball to left field! It is away out and gone! The Dodgers win it, 11 to 10! Unbelievable!”90

Dodger Stadium means change. In 2008 the team moved its longtime Florida spring-training site from Vero Beach to Arizona. To salute a half-century on the West Coast, the Dodgers that March played an exhibition against the Boston Red Sox – the Coliseum’s first baseball since 1961 and game’s largest-ever crowd, 115,300. Permanent seats cut left field by 50 feet to 201, the screen rising from 18 feet to 60 to compensate. The Red Sox won, 7-4.91 That year a $412 million project to build a Dodgers museum, shops, and restaurants around the Ravine was also disclosed.

In person or on TV, the Ravine defines living color. In 2012 Frank McCourt sold the team to Guggenheim Baseball Management, which modernized the park, yet preserved the past. It matched new signage and seating with the original seating color scheme, assigned by Emil Praeger to “mimic the LA sunset.”92 The next year, investing “over $150 million,”93 Guggenheim hired D’Agostino Izzy Quirk Architects to serve a public that bought food, beer, caps, and shirts from LA’s official store and brought children to “play areas.” New President and CEO Stan Kasten was addressing the Average Joe.

Kasten’s view resonated because while “suites and premium areas … had been added,”94 concourses gave Joe Fan little chance to change seating levels, walk around the park, or be entertained. So right- and left-field boards and ultimately other message boards were replaced by “state-of-the-art [high-definition] video boards,” restoring their former hexagon shape but “22 percent larger with 66 percent more active viewing area.”95 Renovation brought wider concourses, “companion seats,” and “improved wheelchair-access areas.”96 New standing-room areas gave “fans a unique view of the game.”97 A better sound system also muted echo.

Meanwhile, flashing strobe arcs were making the Ravine a better-lighted place, later replaced by even brighter LED lights that went on instantly, not gradually, changing the “game experience,”98 Kasten said. A “state-of-the-art wi-fi network and cellular antenna system upped cellphone and internet connectivity from mobile devices.” Change brought brighter signage and more picnic areas,99 new and expanded restrooms, concessions, indoor home and away batting cages, better training and conditioning facilities, and a larger footprint of the Dodgers clubhouse, as Kasten had vowed.

Once he asked, “Where, oh where, is the memorabilia? This is the Dodgers!” – a team proving Faulkner’s saw “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”100 Yearbooks and media guides were hung for public perusal. Staff re-created “MVP Awards, Gold Gloves, Silver Sluggers, the decades of program covers … enlarged and framed like artwork.”101 New entry plazas housed autographed baseballs, life-size bobbleheads, and five-foot replicas of Dodgers Cy Young winners.102 Another change became past “[logos being] … painted onto different areas” from Brooklyn’s only world title in 1955 to “1959 Dodgers 50th Anniversary.”103 Wrote Janet Marie Smith: “There is something about an anchor to the past that makes this a great game today.”104

Outside, in 1962, $6 million in landscaping included planting three palms beyond center field: to Vin, “The Three Sisters.”105 In 2012 they were moved to allow new power in buried duct banks under them, then next year to build the plaza and bullpen-overlook bars. Officials unsure if roots would survive in “burlap bags during construction”106 shifted trees to a temporary site, then planted and dug them up again. The trees now “grace the Dodgers bullpen” – where better to ensure saves? – “carefully replanted” to realign their trunks.107

“More than 3,400 trees cover[ed] the 300 acres of beautiful landscape” in 2001, “maintained by a full-time staff.”108 A decade later each tree displaced for plazas at a ballpark entry was replanted and more than 100 added. Old highway signs were replaced by corrugated metal signs in 1962’s hexagonal scoreboard shape. Red bougainvillea matched the color of the Dodgers’ home uniform number.109 Befitting a camera-phone age, in 2015 Dodger Stadium became the second most Instagrammed site in the world.110

By then, many performers had sung in a park largely defined by Scully’s tenor. Among them: David Bowie, Eric Clapton, Michael Jackson, Elton John, KISS, The Beatles, The Bee Gees, The Rolling Stones, and U2. In 1994 Jose Carreras, Placido Domingo, and Luciano Pavarotti gave a one-night-only concert performance at Dodger Stadium: “Encore – the Three Tenors.” Paul McCartney later starred, with Ringo Starr as guest performer, singing 38 songs in “an epic three-hour concert.”111 Less secularly, Pope John Paul II celebrated Mass there on September 16, 1987.112

“Never say Dodger fans do not love their history,” Smith attests, the franchise’s music between the lines among baseball’s most inspiring.113 Prior to 2022, the uniform numbers of eight players and two managers had been retired: 1 (Pee Wee Reese), 2 (Lasorda), 4 (Snider), 19 (Gilliam), 20 (Sutton), 24 (Alston), 32 (Koufax), 39 (Campanella), 42 (Jackie Robinson), and 53 (Drysdale). Gil Hodges’ number 14 was retired in 2022, Valenzuela’s 34 a year later. All were Baseball Hall of Famers save Gilliam, who died in the 1978 season, and Fernando.114

In 2012-20, Guggenheim’s LA baseball debut, Big Blue each year but the first won the NL West. In 2017 it became the first team to go 43-7 in a 50-game period since the 1912 Giants,115 but lost a seven-game Fall Classic to Houston, notably the Astros’ 13-12 10-inning Game Five victory deemed “one of the greatest World Series games ever.”116 Ten Dodgers including Reese, Campy, and Big D comprised the Ravine’s third-deck Ring of Honor. In May, Scully became the 11th, a mic, not a number, on his plaque.

A year earlier, more than 24,000 at the annual “FanFest” hailed the man who perhaps more than anyone defined Ravine and Dodgers history. “As the Legend said Goodbye, the World of Baseball Paid Loving Tribute,” the 2017 Dodgers Yearbook wrote of Vin’s last radio/TV year.117 On April 11, 2016, LA’s Elysian Park Avenue address was renamed “1000 Vin Scully Avenue.” That September 23, Vin Scully Appreciation Day, he got a key to the City of Los Angeles, tributes from Koufax and Kershaw, actor Kevin Costner, and fellow mic men Jarrin and Steiner, and a Dodgers blue carpet exit for Vin and wife Sandi.118

Scully won a lifetime Emmy, aired 25 World Series, made every major radio/TV Hall of Fame, and was named “Top Sportscaster of All Time” by the American Sportscasters Association. His record 67 years with the Dodgers made Vin integral to the Ravine. At his last home game, a sellout crowd and Dodgers and Giants players, tipping their caps, said so long. After Vin’s last game a week later in San Francisco, he bade farewell, quoting an Irish poem: “May God give you for every storm, a rainbow, For every tear, a smile, For every care, a promise, And a blessing in each trial. For every problem life sends, A faithful friend to share, For every sigh, a sweet song, And an answer for each prayer.”119

In 2017 Fox Television’s Joe Davis became LA’s lead TV play-by-play man, Hershiser on color. Today, Garciaparra, Karros, Jessica Mendoza, José Mota, Stephen Nelson, Tim Neverett, Steiner, Valenzuela, Kirsten Watson, Dontrelle Willis, and Pepe Yñiguez also buoy Dodgers radio/TV.120 In 2018 Jaime Jarrin entered the Ring of Honor121 and Walker Buehler started the franchise’s first combined no-hitter. Chavez Ravine lists 13 no-nos, the first by the Angels’ Bo Belinsky and eight by the Dodgers’ Koufax (three), Bill Singer, Valenzuela, Kevin Gross, Ramón Martinez, and Kershaw.122 In Series Game Three against Boston, Max Muncy’s 18th-inning blast gave LA a victory after the longest postseason set of 7 hours and 20 minutes.123

In 2019 Dodgers attendance peaked at 3,974,309, the team also breaking the NL season record with 279 home runs.124 The 2020 Angelenos outlasted the 29 other teams – and COVID pandemic. In March baseball canceled spring training. In July it ordained a 60-game season, sans spectators.125 The Dodgers’ 30-10 start was the best since the 31-9 2001 Mariners.126 Los Angeles ended the regular season 43-17, its winning percentage a post-1960 expansion high .717. Extrapolated to 162 games, LA’s 116 victories would tie the 1906 Cubs and 2001 Mariners.127 Mookie Betts, acquired from Boston, and A.J. Pollock led in home runs (16), Corey Seager and Justin Turner in average (.307), and Kershaw in victories (6) and ERA (2.16).128

The pandemic extended postseason, the Dodgers sweeping Milwaukee in the wild-card series. They ousted San Diego in the best-of-five Division Series, edged the Braves in the LCS, and beat Tampa Bay in the 2020 Fall Classic.129 Seager won the Series MVP Award.130 LA’s director of baseball operations Andrew Friedman was named Major League Baseball Executive of the Year131 and his team Baseball America’s Major League Organization of the Year132 for winning the bicoastal franchise’s seventh world title since 1955 and first since 1988.

Since then, it has tried to top the topper. In 2021 Los Angeles lost the West for the first time since 2012, but made the postseason a record ninth straight year – 106 victories the most for a team that hadn’t won its division or league.133 A year later, the Ravine hosted the All-Star Game, six Dodgers chosen including starting pitcher Kershaw. LA won a franchise-high 111 sets but lost the 2022 Division Series to San Diego, not advancing despite the divisional era’s best regular-season record. “It’s crushing,” said NL 2016 Manager of the Year Dave Roberts.134

The 2023 Dodgers went 100-62, 16 games ahead of second-place Arizona, but again stumbled in October. In the Division Series, the D-backs tamed Big Blue at Dodger Stadium, 11-2 and 4-2. In Game Three at Phoenix, Arizona became the first big-league team to hit four postseason home runs in an inning.135 After three batters had gone deep, Gabriel Moreno’s drive was ruled a homer, then reversed by instant replay. Unfazed, Moreno smashed a drive “to the moon,” cried TBS broadcaster Bob Costas. It presaged another 4-2 LA loss for the club with the most wins (317) in three years (2021-23) not to make a World Series.136 Brooklyn’s ancient cry, “Wait Till Next Year,” rarely seemed so poignant.

Despite that, by 2023 a $100 million center-field plaza renovation at Chavez Ravine included a children’s playground, relocation there of Jackie Robinson’s statue from the left-field entrance, and display feting “The Legends of Dodger Baseball.” It hailed Steve Garvey, Kirk Gibson, Orel Hershiser, Fernando Valenzuela, Maury Wills, 1949-58 Dodgers pitcher, 1956 Cy Young Award recipient, and founder of baseball’s first community relations department Don Newcombe, and LA’s 1969-80 and 1982 nonpareil pinch-hitter and 1980-2012 coach Manny Mota.137

In 2015 Stan Kasten and Dodgers Chairman and part-owner Mark Walter had commissioned a statue to be unveiled on the 70th anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s breaking the color line – the Ravine’s first. Oakland-based Haitian-American artist Branly Cadet138 was named to create it, prior works including public figures like Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr. in New York City and educator Octavius Catto in Philadelphia. They showed, said Janet Marie Smith, “the power of a bronze to tell the story of a man.”139

Working with widow Rachel and daughter Sarah Robinson, Smith was struck by how the statue heightened the effect of Jackie sliding into home plate. On the sculpture’s base lie several Robinson quotes, the most familiar “A life is not important except for the impact it has on others.”140 On April 15, 2017, 20 years after the pioneer’s number 42 was retired by baseball, Cadet’s statue was unveiled. Baseball’s first Black owner, Magic Johnson, said that “Jackie paved the way”141 for him to invest in the Dodgers, Robinson’s impact having helped end segregation.

On June 18, 2022, another graceful Cadet statue showing Sandy Koufax’s classic leg kick142 was dedicated in the “Legends” area flanking Jackie’s. “As teammates, we were bound together by a single interest and common goal. To win,” the pitcher’s quote read. “Nothing else mattered and nothing else would do.”143 Koufax spoke modestly at the event, saying, “I think my only regret today is that so many are no longer with us,” including the ailing Scully, who died on August 2.144 Sandy’s big-league career began with the 1955-56 Dodgers, Robinson’s last two years before retiring. Vin broadcast each. Any definition of the franchise must accent all three.

When Elysian Park Avenue was renamed in 2016, the Dodgers “planted a double row of trees and firestick plants along the street to celebrate,” Smith wrote.145 Yearly the palms and lilacs blossom as if to coincide with Opening Day: apt for Scully, who helped each season bloom with poetry and gentle humor, and baseball, each year renewing its need for courage and resilience, Vin once musing of an injured player, “He’s listed day to day. Aren’t we all?”

The book A Baseball Century wrote, “More difficult than imagining America without baseball is imagining baseball without the Dodgers.”146 As difficult is imagining the Dodgers without the wonder of Chavez Ravine.

Last revised: July 1, 2024

SOURCES

Thanks to the sources cited under “Interviews by author.” Grateful appreciation is made to reprint play-by-play and color radio text courtesy of The Miley Collection. In addition to sources cited in the Notes, especially the Society for American Baseball Research, the author consulted the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites, box scores, season, and team pages, batting and pitching logs, and other material relevant to this history. FanGraphs.com provided statistical information. Beyond the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted:

Reidenbaugh, Lowell. The Sporting News Take Me Out to the Ball Park (St. Louis: Sporting News Publishing Co., 1983).

Wood, Bob. Dodger Dogs to Fenway Franks: And All the Wieners in Between (New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Co., 1988).

Interviews by author:

Emil J. ”Buzzie” Bavasi, 1978.

Jerry Coleman, 2010.

Bob Costas, 1988.

Jerry Doggett, 1992.

Dick Enberg, 2014.

Pat Hughes, 2022.

Jorge Iber, 2022.

William Johnson, 2005.

Jon Miller, 1991.

Phil Mushnick, 2007.

Vin Scully, 1986 and 1992.

Charley Steiner, 2007.

George Vecsey, 2012.

NOTES

1 Gene Schorr. A Pictorial History of the Dodgers: From Brooklyn to Los Angeles. (New York: Leisure Press, 1985), 104.

2 Frank Finch, The Los Angeles Dodgers: The First Twenty Years. (Virginia Beach, Virginia: Jordan & Company, 1977), 16.

3 Finch, 17.

4 Janet Marie Smith, “How the Firsts Have Fared” (speech, NINE Conference, Phoenix, Arizona, March 2016.)

5 Thomas Harrigan, “Every Ballpark, from Oldest to Newest,” MLB.com, February 22, 2022. https://www.mlb.com/news/mlb-parks-from-oldest-to-newest.

6 Jim Gordon, “Wrigley Field (Los Angeles),” SABR.org. https://sabr.org/bioproj/park/wrigley-field-los-angeles/.

7 https://www.ballparksofbaseball.com/ballparks/los-angeles-wrigley-field/.

8 https://uclabruins.com/facilities/the-rose-bowl/1.

9 Philip J. Lowry, ed., Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major and Negro League Ballparks (New York: Addison-Wesley, 1992), 170.

10 Vin Scully interview, 1992.

11 Green Cathedrals, 168-70.

12 Finch, 24.

13 Finch, 41.

14 Emil J. “Buzzie” Bavasi interview, 1978.

15 Steven Travers, A Tale of Three Cities: The 1962 Baseball Season (Washington: Potomac Books, 2009), 9.

16 Travers, 25.

17 Bavasi interview, 1978.

18 Travers, 9.

19 Travers, 25.

20 “Blue Heaven,” 2018 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 10.

21 https://www.walteromalley.com/en/features/chavez-ravine/Timeline.

22 Finch, 13.

23 Green Cathedrals, 52.

24 https://www.walteromalley.com/en/features/chavez-ravine/Overview/view-all.

25 Finch, 14.

26 https://www.walteromalley.com/en/features/chavez-ravine/Overview/view-all.

27 Matt Borelli, “This Day in Dodgers History: Walter O’Malley Buys Land to Build Dodger Stadium,” dodgerblue.com, February 18, 2022. https://dodgerblue.com/this-day-dodgers-history-walter-omalley-completes-purchase-land-build-dodger-stadium/2022/02/18/.

28 https://www.walteromalley.com/en/dodger-stadium/construction-facts/Page-1.

29 https://www.walteromalley.com/en/dodger-stadium/construction-facts/Page-1.

30 Smith, “How the Firsts Have Fared,” 12.

31 Bruce Adams and Margaret Engel, Baseball Vacations (New York: Fodor’s Travel Publications, 2000), 312.

32 Adams and Engel, 312.

33 Randi Radcliff, “Dodger Stadium’s History, Facts, and Nostalgia,” dodgersway.com, June 6, 2017. https://dodgersway.com/2017/06/06/dodgers-stadium-history/.

34 Smith, “How the Firsts Have Fared,” 13.

35 Finch, 45.

36 Janet Marie Smith, “Ballpark Diaries: Notes from the Field,” NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture 30(1): 16-17.

37 Smith, “Ballpark Diaries: Notes from the Field,” 17.

38 https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/LAD/.

39 Jerry Doggett interview, 1992.

40 2018 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 10.

41 Doggett interview.

42 L. Robert Davids, “Three Men on Third,” Baseball Research Journal (SABR), 1977. https://sabr.org/journal/article/three-men-on-third/.

43 Green Cathedrals, 53.

44 Green Cathedrals, 52.

45 John Thorn, “The Elysian Fields of Hoboken,” ourgame.mlblogs.com, December 2, 2014. https://sabr.org/latest/thorn-the-elysian-fields-of-hoboken/.

46 Travers, 1.

47 Finch, 41.

48 Smith, “How the Firsts Have Fared,” 12.

49 Smith, “How the Firsts Have Fared,” 12.

50 Smith, “How the Firsts Have Fared,” 12.

51 Rowan Kavner, “Vin Scully Was Dodger Baseball,” foxsports.com, August 2, 2022. https://www.foxsports.com/stories/mlb/vin-scully-was-dodger-baseball.

52 Larry Stewart, “There’s No Change in the Booth,” Los Angeles Times, March 20,1998, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-mar-20-sp-30847-story.html.

53 Thomas Heath and Paul Farhi, “Murdoch Adds Dodgers to Media Empire,” Washington Post, March 20, 1998, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1998/03/20/murdoch-adds-dodgers-to-media-empire/4cc70d40-801d-4e53-8a8d-0af1626f0f9e/.

54 Finch, 41.

55 Finch, 42.

56 2013 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 14.

57 Finch, 67.

58 Finch, 97.

59 “Don Drysdale, Hall of Fame Dodger Pitcher, Dies at 56,” New York Yankee Fans Forum, July 3, 1993, https://nyyfansforum.sny.tv/forum/forum/general-baseball-forums/history-trivia-memorabilia/12613008-july-3-1993-don-drysdale-passes-away.

60 Andrew Simon, “Acuña’s Derby Blast Leaves Dodger Stadium,” MLB.com, July 18, 2022, https://www.mlb.com/news/home-runs-hit-out-of-dodger-stadium.

61 Gene Schoor, A Pictorial Picture of the Dodgers: From Brooklyn to Los Angeles (New York: Leisure Press, 1985), 202-203.

62 https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0649836/.

63 Travers, 72-73.

64 2019 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 143, 145.

65 https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/tommy_lasorda_139446.

66 Charley Steiner interview, 2007.

67 Finch, 95.

68 Schoor, 219.

69 Scott Andes, “Farewell Sweet Diamond Vision,” Dodgers Way, January 21, 2013, https://dodgersway.com/2013/01/21/farewell-sweet-diamond-vision/.

70 “Peter Victor Ueberroth,” Encyclopedia.com, May 29, 2018, https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/sports-and-games/sports-biographies/peter-victor-ueberroth.

71 A Martinez, “Veteran Baseball Broadcaster Jaime Jarrin Says Goodbye,” NPR.org, October 14, 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/10/14/1129001701.

72 https://www.mlb.com/dodgers/team/broadcasters.

73 Steiner interview, 2007.

74 Richard Justice, “Lasorda Doesn’t Dodge Rehashing Fateful Pitch to Cardinals’ Clark,” Washington Post, February 14, 1986, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/1986/02/14/lasorda-doesnt-dodge-rehashing-fateful-pitch-to-cardinals-clark/6ac83422-0a40-4677-b9b0-6aa1a48779a7/.

75 https://www.youtube.com.com/watch?v=jeGFSEIONyA.

76 Matthew Moreno, “Tommy Lasorda Receives Lifetime Achievement Award at 17th Annual LA Sports Awards,” dodgerblue.com, March 9, 2022. https://dodgerblue.com/dodgers-tommy-lasorda-lifetime-achievement-award-los-angeles-sports-awards/2022/03/09/.

77 Matthew Moreno, dodgerblue.com, September 28, 2022, https://dodgerblue.com/this-day-dodgers-history-orel-hershiser-breaks-don-drysdales-record-59-consecutive-scoreless-innings/2022/09/28/.

78 https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/h/hershor01.shtml.

79 Matt Kelly, “Sutton’s Numbers Still Boggle the Mind,” MLB.com, January 19, 2021, https://www.mlb.com/news/don-sutton-facts-and-figures.

80 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=10nmbbAQktg.

81 Luke Norris, “Remember When the LA Dodgers Had 5 Rookie of the Year Winners in a Row?” sportscasting.com, October 21, 2020, https://www.sportscasting.com/remember-when-the-la-dodgers-had-5-rookie-of-the-year-winners-in-a-row/.

82 2001 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Dodgers, Inc.), 55.

83 https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/LAD/leaders_bat_season.shtml.

84 https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/LAD/leaders_bat_season.shtml.

85 https://www.mlb.com/news/roberto-clemente-award-2023-nominees.

86 2019 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 154.

87 2019 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 154.

88 Alan Schwarz, “Green to Sit Out on Yom Kippur,” ESPN.com, September 5, 2004, https://www.espn.com/mlb/news/2001/0905/1248286.html.

89 https://www.mlb.com/video/scully-s-touching-speech-c18652293.

90 www.mlb.com/video/dodgers-win-on-homer-fest-c20006559.

91 Eric Stephen, “Dodgers vs. Red Sox LA Coliseum Exhibition,” truebluela.com, June 20, 2020, https://www.truebluela.com/2020/6/20/21293920/dodgers–red-sox-coliseum-exhibition-2008.

92 Smith, “Ballpark Diaries,” 18.

93 Smith, “How the Firsts Have Fared,” 14.

94 Smith, “How the Firsts Have Fared,” 15.

95 2013 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 8.

96 2013 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 6.

97 2013 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 7.

98 Matthew Moreno, “Stan Kasten: New Dodger Stadium Lights Change ‘Game Experience,’” dodgerblue.com, March 20, 2023, https://dodgerblue.com/stan-kasten-new-dodger-stadium-lights-change-game-experience/2023/03/30/.

99 2013 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 8.

100 https://www.goodreads.com/work/quotes/2041161-requiem-for-a-nun.

101 Smith, “Ballpark Diaries,” 13.

102 2013 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 8.

103 2013 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 7.

104 Smith, “Ballpark Diaries,” 13.

105 Smith, “How the Firsts Have Fared,” 15.

106 Smith, “How the Firsts Have Fared,” 15.

107 Smith, “Ballpark Diaries,” 17.

108 2001 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Dodgers, Inc.), 89.

109 Smith, “Ballpark Diaries,” 18.

110 Smith, “How the Firsts Have Fared,” 14.

111 Katie Atkinson, “Paul McCartney Spreads Love with Ringo Starr, Plus More Highlights from Epic Final Tour Stop at Dodger Stadium.” Billboard, July 14, 2019, https://www.billboard.com/music/rock/paul-mccartney-dodger-stadium-concert-recap-8519795/.

112 2001 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Dodgers, Inc.), 89.

113 Smith, “Ballpark Diaries,” 13.

114 Ken Gurnick, “Dodgers’ All-Time Retired Numbers,” MLB.com, December 1, 2021, https://www.mlb.com/dodgers/history/retired-numbers.

115 2018 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 25.

116 2018 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 36.

117 2017 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 17.

118 2017 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 32.

119 2017 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 38.

120 https://www.mlb.com/dodgers/team/broadcasters.

121 2019 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 55.

122 https://www.nonohitters.com/dodger-stadium-no-hitters/.

123 2019 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 39.

124 Ken Gurnick, “Dodgers Set NL Single-Season Mark for Homers,” MLB.com, September 5, 2019, https://www.mlb.com/dodgers/news/dodgers-set-single-season-nl-home-run-record.

125 Mark Feinsand, “Play Ball: MLB Announces 2020 Regular Season,” MLB.com, July 6, 2020, https://www.mlb.com/news/mlb-announces-2020-regular-season.

126 Eric Stephen, “Battle of the Bullpens Tilts Toward Dodgers in Late Home Run Derby with Rockies,” truebluela.com, September 4, 2020, https://www.truebluela.com/2020/9/4/21423734/dodgers-home-run-derby-rockies-bulllpen-recap.

127 Do-Hyoung Park, Andrew Simon, and Chad Thornburg, “Which Teams Won the Most Games in a Season?” MLB.com, October 5, 2022, https://www.mlb.com/news/most-mlb-wins-in-a-season-c289159676.

128 https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/LAD/2020.shtml.

129 Anthony Castrovince, “Wait Is Over! Dodgers Win 1st WS since ’88,” MLB.com, October 28, 2020, https://www.mlb.com/news/dodgers-win-2020-world-series?game_pk=635886.

130 Richard Justice, “World Series MVP Seager 8th in Special Club,” MLB.com, October 28, 2020, https://www.mlb.com/news/corey-seager-named-2020-world-series-mvp.

131 Ken Gurnick, “Friedman Wins Executive of the Year Award,” MLB.com, November 17, 2020, https://www.mlb.com/dodgers/news/andrew-friedman-2020-executive-of-the-year-award.

132 Bill Plunkett, “2020 MLB Organization of the Year: Los Angeles Dodgers,” baseballamerica.com, November 30, 2020, https://www.baseballamerica.com/stories/2020-mlb-organization-of-the-year-los-angeles-dodgers.

133 Blake Williams, “Dodgers’ Streak of NL West Titles Snapped at 8 Years by Giants,” dodgerblue.com, October 3, 2021, https://dodgerblue.com/dodgers-streak-eight-nl-west-titles-snapped-giants-division/2021/10/03/.

134 Juan Toribio, “LA’s Historic Season Ends in NLDS Heartbreak,” MLB.com, October 16, 2022, https://www.mlb.com/dodgers/news/dodgers-lose-nlds-to-padres-eliminated-from-2022-postseason.

135 Associated Press, “Diamondbacks 1st Team to Homer 4 Times in Postseason Inning with Big 3rd vs. Dodgers,” October 11, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/diamondbacks-homers-perdomo-marte-walker-moreno-a04d774b4b90d40e5dbc20de7ca3ed81.

136 AJ Gonzales, “Dodgers Set MLB Record Without 2023 World Series Appearance,” msn.com, October 13, 2023, https://www.msn.com/en-us/sports/mlb/dodgers-set-mlb-record-without-2023-world-series-appearance/ar-AA1iaNZW.

137 Eric Stephen, “Orel Hershiser & Manny Mota to Join ‘Legends of Dodger Baseball’ in 2023,” truebluela.com, February 10, 2023, https://www.truebluela.com/2023/2/10/23594616/orel-hershiser-manny-mota-legends-baseball-honor-2023.

138 https://www.branlycadet.com.

139 Smith, “Ballpark Diaries,” 14.

140 2018 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook, “Paving the Way” (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 155.

141 2018 Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbook, “Paving the Way” (New York: Professional Sports Publications), 155.

142 Juan Toribio, “‘One of a Kind’ Koufax Immortalized With Dodger Stadium Statue,” MLB.com, June 18, 2022, https://www.mlb.com/news/sandy-koufax-statue-unveiled-at-dodger-stadium.

143 https://www.branlycadet.com/sandy-koufax-monument.

144 Anthony Castrovince, “Vin Scully, Legendary Broadcaster, Dies at 94,” MLB.com, August 3, 2022, https://www.mlb.com/news/vin-scully-legendary-announcer-dies.

145 Smith, “Ballpark Diaries,” 18.

146 Jeremy Friedlander, ed., A Baseball Century: The First 100 Years of the National League (New York: Rutledge Books, 1976), 177.