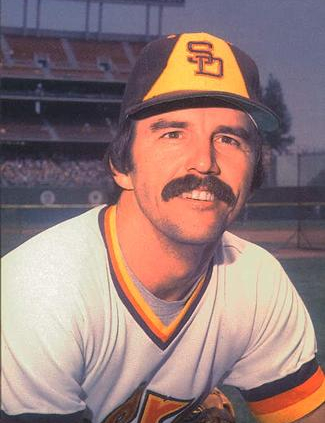

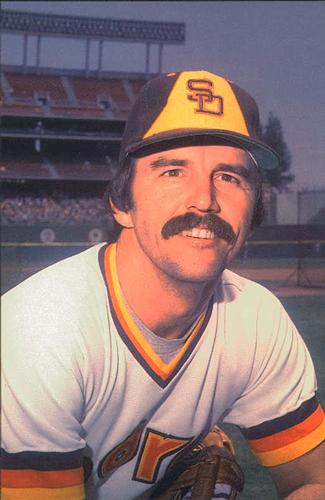

Kurt Bevacqua

Kurt Bevacqua played in 15 major league seasons with the Cleveland Indians, Kansas City Royals, Pittsburgh Pirates, Milwaukee Brewers, Texas Rangers, and San Diego Padres from 1971 to 1985. Bevacqua crafted a career as a pinch hitter and utility player at a time when that role was needed on a major league roster and for a 10-year stretch from 1975-1985, Kurt Bevacqua was one of baseball’s great pinch hitters and great characters. He caught fire as a designated hitter in the 1984 World Series, hitting .412 with two home runs, two doubles, and four RBIs. Bevacqua’s legacy transcends numbers and his .236 career batting average, marked by grit, tenacity, a World Series hot streak and a legendary feud with Tommy Lasorda. His post-baseball life has been dedicated to community, charity, and his fellow major league ballplayers.

Kurt Bevacqua played in 15 major league seasons with the Cleveland Indians, Kansas City Royals, Pittsburgh Pirates, Milwaukee Brewers, Texas Rangers, and San Diego Padres from 1971 to 1985. Bevacqua crafted a career as a pinch hitter and utility player at a time when that role was needed on a major league roster and for a 10-year stretch from 1975-1985, Kurt Bevacqua was one of baseball’s great pinch hitters and great characters. He caught fire as a designated hitter in the 1984 World Series, hitting .412 with two home runs, two doubles, and four RBIs. Bevacqua’s legacy transcends numbers and his .236 career batting average, marked by grit, tenacity, a World Series hot streak and a legendary feud with Tommy Lasorda. His post-baseball life has been dedicated to community, charity, and his fellow major league ballplayers.

Born on January 23, 1947, in Miami Beach, Florida, Kurt Anthony Bevacqua was raised by his parents in the same town. His stepfather, Mario Bevacqua, was chief bellhop of the Fontainebleau Hotel for 23 years. He not only loved baseball but also could teach a boy the value of a well-bet two-iron golf shot.1 His mother, Ethel (Cole), like many women at the time, was a homemaker raising Kurt and younger brother Rick. She was a member of choral group Sweet Adelines. Bevacqua was never pushed into sports; he truly loved playing and competing. He spent most summers and weekends at Moore Park. “I would leave in the morning, round up friends, head to the park where you could check out equipment,” he said. “The park closed from 12-1. Went home for lunch and we would go back and play until close. Very much of a ‘be home when the streetlights go on’ childhood.”2

Bevacqua’s favorite teams growing up were the Yankees and the Dodgers, who then dominated baseball. Mickey Mantle was his favorite player. “I had a Brooklyn Dodgers hat, too, and that was my favorite hat,” he said in 2020. “So, as most people know, I don’t like the Dodgers now, but I still wear a Brooklyn Dodgers hat that my son bought me.”3

Bevacqua honed his baseball skills in Little League and American Legion. He attended North Miami High School, where he earned All-City honors. In the spring of 1959, he served as a visiting batboy for the Baltimore Orioles in spring training. He took ground balls with Luis Aparicio.4 “I got a lot of help from Bobby Richardson, and I know working around big-league players helped my batting,” he said.5

After high school, Bevacqua transitioned to Miami Dade North Community College, a baseball powerhouse under College Baseball Hall of Famer Demie Mainieri. Bevacqua said the talent on the team was so deep that fellow North Miami alum Steve Carlton went out for the team and was told that he would not be a starter.6 More than 100 of Mainieri’s former players were drafted or signed by professional teams, and 30 of them made it to the major leagues.7 Bevacqua endeared himself to his coach with his outrageous hustle and ridiculous cockiness. “He’d run to the plate to hit,” says Mainieri. “Nothing intimidated him. We’d be playing the best teams, against the best pitchers, and he’d be yelling, ‘Give us your ace! We wanta see your ace!’”8

Drafted by the New York Mets in the 32nd round of the MLB June Amateur Draft in 1966, then by the Atlanta Braves in the sixth round of the Secondary Draft in January of 1967, and finally by the Cincinnati Reds in the 12th round of the Secondary Draft in June of 1967, Bevacqua signed with Reds scout Sheldon “Chief” Bender. When Bevacqua’s professional career began in the Reds’ minor league system, he played every position except pitcher and catcher; that versatility would define his career. In 1968, with the Tampa Tarpons of the Class A Florida State League, he showed flashes of potential. Teammate Bob Hall from Eau Claire, Wisconsin, was the first person who told Bevacqua that he would make the major leagues.9 In 1969, Bevacqua advanced to Double-A Asheville with teammate Dave Concepción. By 1970, he’d climbed to the Triple-A Indianapolis Indians, where he hit .261 and began to refine his approach at the plate.

In the spring of 1970, Bevacqua earned the nickname “Dirty Kurt,” which fit his relentless, hard-nosed style. That spring in Florida, the minor leaguers would dress and get on the bus in the early morning. They’d head across state to towns hours away like Cocoa Beach, play the B game, and face the major-league starters, who worked early to beat the afternoon heat. A long bus ride back to Tampa in uniform would follow. On arrival the minor leaguers were expected to finish the big-league spring training game. After the game, infield coach Alex Grammas lined up all the minor leaguers at shortstop for infield work. Fungoes were sprayed between second base and third base. Ten stops in a row were required. Grammas made everyone dive for the last ones. This was the daily routine.

Given Bevacqua’s tenacity, his uniform was dirty daily. One day, the Reds minor leaguers faced Houston’s J.R. Richard in the B game. Then they rode the bus for three hours back to the big-league game, played the rest of the game, then fielded Grammas’ postgame fungoes. For a guy whose uniform was always dirtiest on the team, that day was filthier than usual. Pete Rose had left the big-league game early but was still at his locker when Bevacqua had finished fungoes, Rose looked Bevacqua up and down and said, “You’re dirty [expletive]. You’re Dirty Kurt.”10

Bevacqua was the last player cut after spring training in 1971. “I was called into Sparky [Anderson]’s office. I knew what was going to happen.,” he said. “I had had a great spring and really thought I would make the team. Sparky told me that the club was going for more experience off the bench in Ty Cline and Jimmy Stewart. I was shocked.”11 He was sent to Indianapolis, then quickly traded to the Cleveland Indians and assigned to Triple-A Wichita. After the trade, Bevacqua told his mother, “Don’t worry, you’ll be able to see me on TV in about a month.”12

Indeed, it was just about a month later when Ken Harrelson abruptly retired from baseball to play professional golf. That opened an opportunity for Bevacqua, and he played in his first major-league game against the Red Sox at Fenway Park on June 22, 1971. Bevacqua played in 55 games mostly at second base. In a July 16 game against the Royals, he went 2-4 with a 3-RBI triple and scored a run in an 8-4 Cleveland victory.

Sent down to Triple-A Portland at the start of 1972, Bevacqua said, “I didn’t think they gave me enough of a chance for work in spring training.”13 He hit .313 at Portland and earned a late-season call-up. That November, Bevacqua was traded to the Kansas City Royals. He made the 1973 roster and saw playing time in 99 games across in the infield and outfield. On June 1, Bevacqua started what became a trend in his career, hitting a home run against his former team. With one out, Bevacqua drilled a solo shot against Indians reliever Tom Hilgendorf, giving the Royals a 5-4 win.

That offseason, he was traded to Pittsburgh. After limited playing time in 1974, Bevacqua was traded back to Kansas City in July. George Brett’s Rookie of the Year season cut Bevacqua’s time in Kansas City short. His contract was sold to the Milwaukee Brewers during spring training 1975.

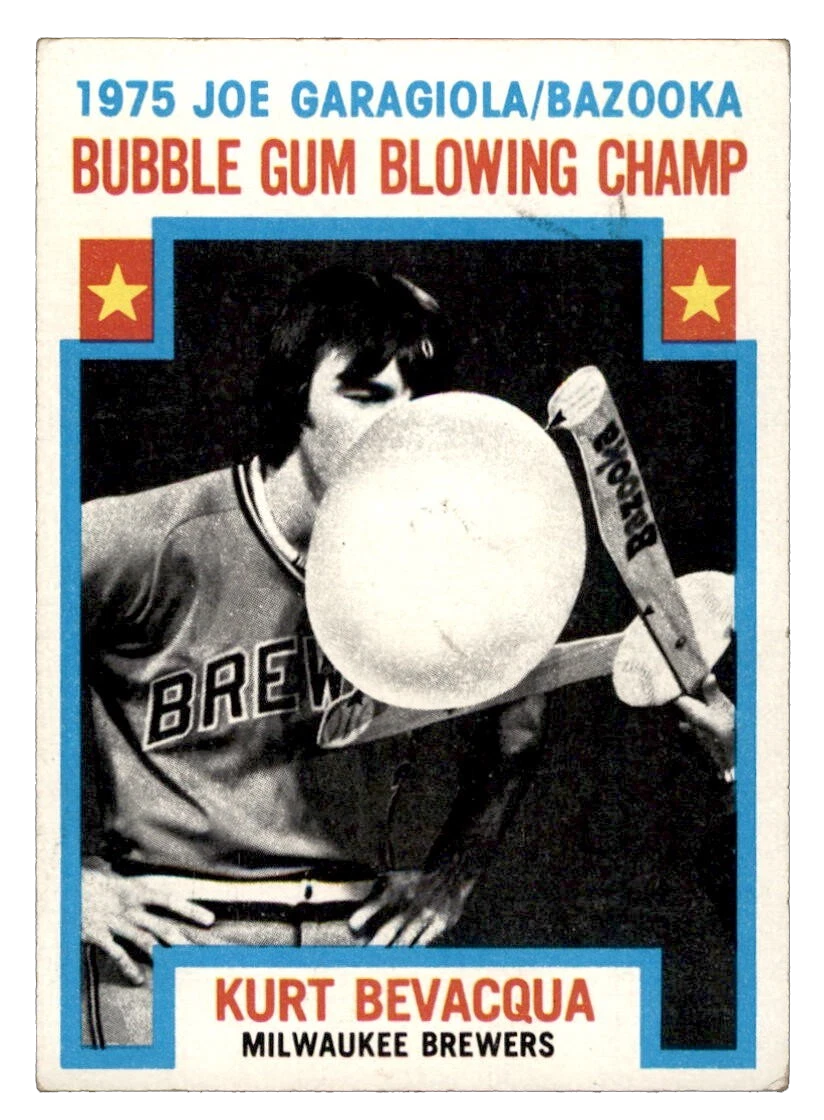

That season, the Joe Garagiola Bazooka Big League Bubble Gum Blowing Championship put Bevacqua on the national stage. “Back then there was Game of the Week. It was the only national broadcast,” Bevacqua said. “We always knew where the cameras were and when they were pointed in the dugout. Guys would try anything to be on camera. Mine was to slide in frame and blow bubbles. So, we are on Game of the Week, Joe Garagiola came up to me before the game, well before the contest ever started, and he goes, ‘Would you be interested in being in a bubble gum blowing championship?’ He says, ‘We’re gonna have a championship and have a representative from each team, and I’m picking you to win.’”14 The contest began in August 1975 with each team having its own competition. Then from a round of two- and three-player “blow-offs,” a pair of league champions emerged: Johnny Oates of the Philadelphia Phillies and Bevacqua.15 The championship aired on a special episode of the Baseball World of Joe Garagiola before Game Three of the 1975 World Series in Cincinnati. Bevacqua prevailed and was commemorated with a special 1976 Topps baseball card. When asked, he has often said, “The trick is to not blow but breathe into the bubble.”16

That season, the Joe Garagiola Bazooka Big League Bubble Gum Blowing Championship put Bevacqua on the national stage. “Back then there was Game of the Week. It was the only national broadcast,” Bevacqua said. “We always knew where the cameras were and when they were pointed in the dugout. Guys would try anything to be on camera. Mine was to slide in frame and blow bubbles. So, we are on Game of the Week, Joe Garagiola came up to me before the game, well before the contest ever started, and he goes, ‘Would you be interested in being in a bubble gum blowing championship?’ He says, ‘We’re gonna have a championship and have a representative from each team, and I’m picking you to win.’”14 The contest began in August 1975 with each team having its own competition. Then from a round of two- and three-player “blow-offs,” a pair of league champions emerged: Johnny Oates of the Philadelphia Phillies and Bevacqua.15 The championship aired on a special episode of the Baseball World of Joe Garagiola before Game Three of the 1975 World Series in Cincinnati. Bevacqua prevailed and was commemorated with a special 1976 Topps baseball card. When asked, he has often said, “The trick is to not blow but breathe into the bubble.”16

Bevacqua saw regular work for Milwaukee in 1975, but in 1976 he was used sparingly, with just seven plate appearances, mostly as a late-inning pinch-runner for Hank Aaron. On May 30, 1976, Bevacqua pinch-ran for George Scott, scoring the winning run, but was demoted to Triple-A Spokane after the game. While Bevacqua punished Pacific Coast League pitching, he hoped for opportunity with expansion. The Seattle Mariners’ first general manager, Lou Gorman, previously director of player development for the Royals, knew Bevacqua well. Thus, Seattle purchased his contact that October.

Bevacqua had a great spring in 1977, batting .467 with several game-winning hits. Even so, he was unexpectedly cut. “As I understand it, Danny Kaye [then Seattle’s part-owner] heard me cussing on the bench one day, and there were some kids around,” he said. “When they cut me, they said I was a ‘bad influence’ on younger players. Hell, I was a monk compared to some of them. But instead of starting, I was in the street. I wound up with Texas, which traded me to San Diego in 1978, so it worked out O.K., but at the time I wasn’t too happy about it.”17

After being released, Bevacqua hit the phones to find a baseball home, landing with the Rangers. His self-described “wackiness and innate optimism” led to his continued presence in the game. Bevacqua was able to negotiate a contract with Rangers owner Brad Corbett at a birthday party held at a country club. He shared time at third base and designated hitter with John Lowenstein in 1978 but did not deliver and was traded to the Padres.18

San Diego quickly became his home. During the 1979 season, he saw time at first base, second base, third base, and left field. Bevacqua often rose to the occasion. On August 29, 1979, in a start at third base, he singled, doubled, and drove in two of the three Padres runs in a victory over the Cubs – one of his six games that season with multiple RBIs.

The 1980 Padres were inconsistent in play and plan – the team was called a soap opera in the press. Nonetheless, Bevacqua had established himself as one of the game’s premier pinch-hitters. The San Diego press questioned why he was not playing more. On May 18, 1980. against the Cubs, down 3-0, Bevacqua pinch-hit in the seventh inning and drove in two runs. He stayed in the game at second base and batted again in the ninth inning, facing Bruce Sutter, then one of the game’s premier closers. Bevacqua singled to center, scoring Paul Dade and Dave Winfield for the walk-off win. For the day, he was 2-for-2 with four RBIs.

Yet that performance still did not translate into more playing time.19 Bevacqua, hitting .300, asked for a trade and went to the press.20 At the All-Star break, the team fired general manager Bob Fontaine and hired “Trader” Jack McKeon as replacement.21 Bevacqua got his wish in a 2 AM phone call from McKeon and was sent to Pittsburgh.22

The Pirates were the defending World Series champion when Bevacqua joined the team. The culture change renewed “Dirty Kurt.” After the trade he said, “I was with the Pirates in 1974, and they haven’t changed a bit. When the game was over, everybody came into the clubhouse saying, ‘We’ll kick them tomorrow.’”23 Bevacqua finished the season and spent most of 1981 with the Pirates. “They were some of the best teammates. Willie Stargell was as good as it gets. He was the real deal,” he said.. “Dave Parker in his prime, what a tremendous ballplayer and guy. Dock Ellis too. I connected with those guys. The whole team was a real team.”

However, Bevacqua continued, “The politics of the game limited my opportunities with the Pirates.”24 The 1981 season was marred by the longest in-season strike in baseball history. Bevacqua was the Pirates’ assistant player representative, and he was vocal. He was one of 10 major-leaguers in strike negotiations. Bevacqua explained, “I came here because I’m an average major-league player, not a superstar, the kind of player who will be affected by the owners’ compensation proposal.”25 He added, “I sat there and listened, and I didn’t see any sign of any kind of settlement whatsoever. The only thing I saw was adamancy. I’m ready to sit out all season if I have to, and when the strike started that was the last thing I wanted to do. We’re no closer to a settlement than we were a year ago.”26

When the players held a brief two-day strike in 1985, Bevacqua recalled the 1981 stoppage. “A lot was written on me because Bob Boone, Dave Winfield, and Mike Schmidt were there, and all of sudden, Kurt Bevacqua shows up. I said what I thought. Well, the day they settled, I was sent to the minors. Anything can happen. If a player is dumped on, it’s always the extra man.”27 Sent to Triple-A Portland to make room for Bill Robinson, Bevacqua announced to the press that he would not go down to the minors at age 34. Willie Stargell had a long talk with his friend and said, “Keep the uniform on your back.”28 He returned in September but was released by the Pirates after the 1981 season.

San Diego and Bevacqua were a match made twice. By 1982, the Padres had turned a corner; according to Bevacqua, “They are doing things that are important to a winning team.”29 He had signed with the club in the offseason, a veteran on a youthful Padres squad, including rookie Tony Gwynn. Bevacqua’s skills were in demand and there were rumors that the Dodgers were interested in signing him.30 Dick Williams, by then well-known as one of the finest managerial turnaround artists, fired up the Padres clubhouse. He demonstrated faith in Bevacqua’s ability to pinch-hit. The veteran became the unofficial clubhouse spokesman, unafraid of “Dirty Kurt” commentary to the press.

That season the Dodgers-Padres rivalry heated up. According to Bevacqua, the agitation started on June 29, 1982, when San Diego beat L.A. 7-5 at Dodger Stadium in 10 innings. In the top of the ninth inning, Jerry Reuss was just three outs away from his 10th win of the season and a possible 4-0 shutout. The Padres rallied. Bevacqua, playing first base, doubled to left-center, scoring Sixto Lezcano and moving Terry Kennedy to third. The score was 4-2 with no outs. Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda went to the mound to get Reuss and called his bullpen. Bevacqua’s double had knocked Reuss out of the game. Lasorda verbally unloaded on Reuss and stared down Bevacqua at second. “He’s yelling at Reuss but looking at me. He is calling me an [expletive] hitter. I yelled at Lasorda, grabbed my crotch and told him where to stick it and next thing I knew Alan Wiggins was tapping me on the shoulder telling me that Dick Williams sent him in to pinch run. So, I left the field upset at Williams and Lasorda,” Bevacqua said.31

The Padres scored five runs that inning, but the Dodgers tied it in the bottom of the ninth to force extra innings. Wiggins drove in two in the 10th for the Padres’ biggest comeback of the year.32

Bevacqua’s most memorable moment of 1982 came in a game the next day – in which he never played. In the nightcap of the June 30 doubleheader, Broderick Perkins homered off Tom Niedenfuer in the ninth inning. The next pitch hit Joe Lefebvre in the helmet. Bevacqua, who was not in the game, charged the mound; he was stopped by first base umpire Joe West and ejected. He was the first and only one out of the dugout.

On July 3, Niedenfuer was fined $500 for the beaning. After learning about the fine, Bevacqua told reporters, “They ought to fine the fat little Italian who ordered the pitch.”33 The reference was obvious and led to Lasorda’s expletive-laden rant the next day. A sanitized version was published on July 5 as, “If I were going to order a pitcher to throw at a hitter, it wouldn’t be at .170 hitters like Bevacqua and Lefebvre. When I was pitching, I would send a taxicab to pick up guys who hit like they do.”34

The full audio came out a few weeks later. In it, Lasorda disputed that he ordered the beanball and claimed, “[Expletive] Bevacqua couldn’t hit water if he fell out of a [expletive] boat.”35

In the press, a feud ensued. For the Padres and their developing rivalry with the Dodgers, it was marketing gold, according to former Padres Vice President of Marketing Andy Strasberg. “Both Lasorda and Bevacqua took advantage to keep the story alive. They knew that it had legs,” he said.36 According to Strasberg, “The Padres needed a rival. The Dodgers had the Giants, but the rant gave us the opportunity to promote a rivalry. It didn’t hurt that the team was improving against the talented Dodgers.”37 The rant was national sports talk radio fodder, with KLAC’s provocateur Jim Healy fanning the flames.

The rivalry continued for years. By midseason 1985, the story still had legs. On June 29, the San Diego Madres, a non-profit that provides financial assistance for youth baseball and softball, held a luncheon with Lasorda and Bevacqua as featured guests and Strasberg as emcee. A capacity crowd enjoyed the afternoon. Lasorda and Bevacqua were both gentlemen and funds were raised for the Madres.

Bevacqua recalled, “I saw him a few times after the incident, but never really talked about it. As a matter of fact, I did a luncheon with him when I was still playing when the Dodgers came into town.”38 When Lasorda died in 2021, Bevacqua said in an interview, “It was never hate…He was the kind of guy that you cannot stand when you are on the opposite side of the field, but when you are on the same side you love ’em.”39

The 1983 Padres added longtime Dodgers rival Steve Garvey. Garvey cost Bevacqua time at first base, but a fast and lasting friendship developed. Bevacqua sported a “Steve Garvey is My Shadow” t-shirt in spring training.40 They became San Diego’s odd couple. “A winning baseball team is more than just good players, it’s a chemistry, a combination of factors. I supply the flakiness,” said Bevacqua.41

On July 14, Bevacqua launched a pinch-hit grand slam, the first in the majors since 1975, to put the Padres ahead of the Pirates 6-3. It was not a day to celebrate, however – the Pirates put up four in the ninth. When asked for comment, he replied, “Oh bleep.”42

As a pinch-hitter in 1983, he batted .412 with one HR and 16 RBIs.43 However, the season wound up as a disappointment for the Padres, who finished in fourth place with a .500 record, as they had the year before.

Bevacqua was also a fan favorite off the field: Padre Fever Day, charity luncheons, and the Michelob-Kurt Bevacqua Celebrity Golf Classic were all part of his off-field community work. The range of causes included St. Madeleine Sophie Center, San Diego Children’s Hospital, St. Jude, and more. “It comes from a place of being in a position to take advantage to help.” Bevacqua said. He also started a Padres newspaper, Baseball Gold with Fred O. Rodgers; its circulation grew to more than 50,000.44

The 1984 Padres continued to beef up their veteran presence. Rich “Goose” Gossage was acquired in free agency. Eight days later owner Ray Kroc, whose purchase of the franchise in 1974 kept the team in San Diego, passed away. The McDonald’s builder had been determined to bring a winning team to the city. The Padres were predicted to win the National League West Division.45 They fulfilled that expectation, winning a team-record 92 games and spending 145 calendar days in first place.

The team famously brawled with the rival Atlanta Braves on August 12. Bevacqua, who was not in the game, was hit by a beer and charged into the stands. A total of 17 players were ejected.46 “It was one of those deals where you’re watching out for your teammates…Did it go overboard a little bit? Eh, maybe. But looking back at it, we probably would have done everything basically the same,” Bevacqua said.47

For Bevacqua himself, the regular season performance was hot and cold. At the end of June, he was batting .333, but that mark fell until September 14, when he doubled home two runs to give the Padres a 4-2 win over the Houston Astros.48 “A pinch-hitter on a winning club doesn’t bat as much as a pinch-hitter on a fourth, fifth or sixth place club,” he said. “I haven’t felt too bad lately.”49

The Padres, in the postseason for the first time, faced the red-hot Chicago Cubs, in the postseason for the first time since 1945. Opportunities were scarce for Bevacqua in the NLCS: he had only two at-bats, both times pinch-hitting for Dave Dravecky. In Game Two, Bevacqua grounded into a double play in the eighth inning. In the series finale, Game Five, he flied out to center field in the fifth inning before the Padres completed their improbable comeback from a two-game deficit to win the National League pennant.

The 1984 World Series was played with American League rules, so the Padres added the designated hitter. Dick Williams selected Bevacqua for the role despite his meager .200 batting average, one home run, and nine RBIs in 80 at-bats in the regular season.50 In retrospect, Williams’ selection was not a surprise. According to Bevacqua, “He was the kind of manager who basically pinch-hit me for almost everyone in the lineup with the exception of Gwynn and Garvey over those few years. He put me in the middle of the lineup when Pascual Pérez pitched against us his next start after the brawl in San Diego. He put me right smack dab in the middle of the lineup that night, hitting fourth. He then found a place for me in the lineup during the World Series when other managers probably wouldn’t have. But he must have known something that I was the kind of player that could rise to the occasion. I think that’s one of the reasons I look back at Dick so kindly.”51

Game One of the 1984 World Series, at Jack Murphy Stadium, was a battle. Jack Morris masterfully used his split-finger fastball to jam and get out of jams. The Tigers held a 3-2 lead. Leading off in the seventh inning, Bevacqua slashed a drive down the first base line into the right field corner and under the in-play bullpen bench. Rounding second, he got the sign from Ozzie Virgil, stumbled, then made for third base. Kirk Gibson fired to Lou Whitaker, who heard the roar of the San Diego crowd, turned and fired to nail the head-first sliding Bevacqua easily.52 With no outs, it was a monumental error. What could have been a game-tying run was a costly out.

Bevacqua did not realize how big this base-running gaffe would be in the media. To the Padres’ credit, Williams, Virgil, and Bevacqua all took the blame as their own. Bevacqua was second-guessed and badgered post-game. “I can say this now, the plan was to run on Gibson. We thought he had a weak arm. I went for it, I stumbled, and we lost. If we win Game One, then we go to Detroit up 2-0.” Bevacqua recalled.53 He vowed to himself to atone for that mistake.54

He did so straight away. In Game Two, held the next night (October 10), Bevacqua gave the Padres franchise its first World Series win by blasting a three-run homer off Dan Petry for a 5-3 Padres victory, tying the Series at one game apiece.

His trot around the bases created a stir with Sparky Anderson, by then Tigers manager. Bevacqua pirouetted before first base, thrust his index finger at second base, and blew kisses to the crowd while rounding third base.55 “It’s probably the most jubilant moment of my career.” Realizing the magnitude of this understatement, “Probably? What a dumb statement,” Bevacqua told reporters after the victory.56

Garvey told reporters, “He came back into the dugout with that look of his. It’s kind of a far-off Jack Nicholson look. You know he’s there physically, but you know he’s someplace far away mentally.”57

Bevacqua, now a World Series star, was booked on The Today Show via satellite from Detroit. As the Series moved to Detroit, however, the momentum, however, shifted to the Tigers. Although Bevacqua singled in Game Three and doubled in Game Four, both were San Diego losses.

In Game Five, Bevacqua drew a walk and scored on a Bobby Brown sacrifice fly in the fourth, which evened the score at 3-3. By the seventh inning, the Tigers had pulled ahead 5-3, when Bevacqua homered to left field off Cy Young Award winner Willie Hernández. It was not enough – the Padres fell, 8-4.

Bevacqua led his club in the Series, batting .412 and slugging .882 with two HRs and four RBIs. “What disappoints me most is that we didn’t get this thing back to San Diego. The fans deserved it,” he told reporters.58

Offseason publicity took the tone of Bevacqua the ballplayer rather than the off-the-wall persona. “He makes it easier to come to the park,” said Tony Gwynn.59 Bevacqua started writing a weekly inside baseball column for the Blade-Tribune. He also put himself on the cover of the January 1985 issue of Baseball Gold. “Actually, my editor did it. He said, ‘You’re the only one from the Series we could honestly single out.’”60 The media published introspective articles on the game’s premier pinch-hitter. “I hear guys say, ‘I owe the game of baseball everything.’ I don’t feel I owe it anything. I know I’ve put a lot more into it than I’ve gotten out of it.”61

Though Bevacqua was more serious, he was still able to pull a great baseball prank. On April 1, 1985, he bewildered listeners of the KBZT radio phone-in show. He announced that the Padres had traded Tim Flannery to Milwaukee for Rollie Fingers, and then traded Fingers, Steve Garvey, and Gerry Davis to the Yankees for Don Mattingly and Willie Randolph. Bevacqua then hung up, forgetting to say that it was an April Fool’s gag. He called back, but it took hours to get through as the KBZT listeners jammed the phone lines.62

In 1985, the Padres could not recapture the magic of 1984 and slid into third place in the NL West. After his heroics in the Fall Classic, Bevacqua reverted to statistical norm, but he did crank two grand slams that June. In the final season of his contract, Bevacqua described a recurring dream on his San Diego radio show. He would be traded and return to the Padres as a free agent. That dream was unfulfilled and he filed for free agency in November. The Padres did exercise the right to arbitrate with Bevacqua.63 At the end of the one-month window, the team declined to offer a contract but did extend a non-roster invitation to 1986 spring training. Bevacqua said, “There comes a time when you get fed up with being a slab of meat and that’s what my situation here has come down to. I might even consider my options outside of baseball.”64

Bevacqua got into eight games in camp in 1986, batting .316 with four RBIs, but it was not enough. He was cut in late March. “Kurt did a lot of good things for this club. He’s been a very important piece to our puzzle,” said Gwynn on learning that Bevacqua had been released.65 Dirty Kurt’s playing days were over.

Unknown, but speculated at the time, was major-league ownership’s collusion against free agents.66 Bevacqua was one of 62 players from 1985 who were frozen out.67 The MLBPA eventually filed grievances, and a $280 million settlement to over 650 players in November 1990 was reached, but payments for damages with interest were not awarded until 1995. Bevacqua received $272,012.42 for lost jobs and $13,600.62 for lost labor mobility.68

Broadcasting was Bevacqua’s next role. He worked on a call-in sports show, “San Diego Sportsline” and auditioned with NBC opposite Marv Albert.69 He landed the job on the backup Game of the Week. Later he had roles with ABC and ESPN. Bevacqua remained in the public eye and popular in San Diego. According to Strasberg, “Kurt is one of the few ballplayers that is also a fan.”70

As of 2025, Bevacqua and wife Cynthia resided in the San Diego area and were parents to five children. In addition to his charity work, Bevacqua ran the Major League Baseball Retired Players Association, a 501(c)(3) non-profit with the motto of “Players helping players.” The group focused on pensions, licensing payments, and other issues facing retired ballplayers while giving back to the community. “There is not the support that most former ballplayers think there is,” Bevacqua said. “MLBRPA is set up to help players and their legacy.”71

Last revised: July 28, 2025

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Kurt Bevacqua and Andy Strasberg for their input.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and David Bilmes and fact-checked by Tony Oliver.

Photo credit: Kurt Bevacqua, Trading Card Database.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the SABR Weir Collection, Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, baseballalmanac.com and LA84 Foundation Digital Library Collections.

Notes

1 John Underwood, “A Great Role Player,” Sports Illustrated, July 1, 1985, https://vault.si.com/vault/1985/07/01/a-great-role-player

2 Bevacqua telephone interview with author, May 20, 2025. (Hereafter Bevacqua telephone interview.)

3 Rocco Constantino, “Dirty Kurt: Kurt Bevacqua,” BallNine, November 12, 2020, https://ballnine.com/2020/11/12/dirty-kurt-kurt-bevacqua/

4 Bevacqua telephone interview.

5 Neil Amdur, “Miami High, Southwest Land Four Players Each,” Miami Herald, May 11, 1965: 25.

6 Bevacqua telephone interview.

7 2014 College Baseball Hall of Fame Inductees, https://www.mlb.com/college-baseball-hall-of-fame/class-of-2014#mainieri. (last accessed June 4, 2025).

8 Underwood, “A Great Role Player.”

9 Bevacqua telephone interview.

10 Bevacqua telephone interview.

11 Bevacqua telephone interview.

12 Al Levine, “Bevacqua has optimism plus a chance to play,” Miami News, May 18, 1971: 33.

13 Charlie Nobles, “Bevacqua says Orioles were ready to go home,” Miami News, September 30, 1972.

14 Bevacqua telephone interview.

15 Tom Shieber, Bubble Play, National Baseball Hall of Fame, https://baseballhall.org/discover/short-stops/bubble-play (last accessed June 4, 2025).

16 Bevacqua telephone interview.

17 Underwood, “A Great Role Player.”

18 Bevacqua telephone interview.

19 Bevacqua telephone interview.

20 “Bevacqua want out of Padres,” Daily Times-Advocate, July 10, 1980: 43.

21 “Padres face a major shakeup,” Daily Times-Advocate, July 9, 1980: 33.

22 Bevacqua telephone interview.

23 Dan Donovan, “Dirty Kurt makes typical debut as Pirate”, Pittsburgh Press, August 6, 1980: 51.

24 Bevacqua telephone interview.

25 Jerome Holtzman, “Baseball Owners, Players haven’t reached first base,” Pittsburgh Press, June 27, 1981: 8.

26 Associated Press, “Baseball negotiations break down,” The Times, Saturday June 27, 1981: 6.

27 Kenneth Reich, “Strike III”, Los Angeles Times, August 7, 1985: 43.

28 Underwood, “A Great Role Player.”

29 Gary Hyvonen, “Bevacqua knows how to help in a pinch,” North County Times, March 15, 1982: 17.

30 John Maffei, “Jones Spoiling Padre Plans for Gwynn,” Daily Times-Advocate, April 23, 1982: 31.

31 Kurt Bevacqua, email correspondence with author, May 24, 2025.

32 Steve Dolan, “Padres rally twice, win in 10th, 7-5,” Los Angeles Times, June 30, 1982: 27.

33 Chris Cobbs, “Bevacqua ‘Fine Lasorda, Too’,” Los Angeles Times, July 4, 1982: 37.

34 Dan Hafner, “Bevacqua’s comment, of course, infuriates Lasorda,” Los Angeles Times, July 5, 1982: 17

35 Tommy Lasorda meltdown about Kurt Bevacqua full audio, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fzjWQF1oP2M (last accessed May 25, 2025).

36 Strasberg telephone interview with author, May 27, 2025. (Hereafter Strasberg telephone interview.).

37 Strasberg telephone interview.

38 Constantino, “Dirty Kurt: Kurt Bevacqua.”

39 Fox 5 San Diego, “Former Padre Pays Respect to Tommy Lasorda,” January 8, 2021 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7WBNpxsvjxo (last accessed May 14, 2025).

40 Don Norcross, “Steve Garvey the newest Padre has been accepted,” Daily Times-Advocate, March 25, 1983: 23.

41 Underwood, “A Great Role Player.”

42 Larry Weinbaum, “Pirates trip up Padres,” Daily-Times Advocate, July 15, 1983: 21.

43 Larry Weinbaum, “Feeling is relaxed as Padres open spring training,” Daily Times Advocate, February 27, 1984: 15.

44 Craig Muder, “#Cardcorner: 1980 Topps Kurt Bevacqua,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, https://baseballhall.org/discover/CardCorner-1980-Topps-Kurt-Bevacqua (last accessed May 22, 2025).

45 Bob Matthews, “Padres’ pennant chances are more than just a prayer,” Statesman Journal, March 31, 1984: 38.

46 Bill Nowlin, August 12, 1984: Braves-Padres brawl leaves 17 players ejected in one game, SABR, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/august-12-1984-braves-padres-brawl-leaves-17-players-ejected-in-one-game/ (last accessed May 2, 2025).

47 Constantino, “Dirty Kurt: Kurt Bevacqua.”

48 Dan Hafner, “Padres Win, and Magic Number is Six”, Los Angeles Times, September 15, 1984: 60.

49 Steve Dolan, “Bevacqua makes some noise with his hitting as Padres top Astros,” Los Angeles Times, September 15, 1984: 21.

50 Underwood, “A Great Role Player,”

51 Constantino, “Dirty Kurt: Kurt Bevacqua.”

52 Fred Mitchell, “San Diego crowd help Tigers win World Series opener,” Chicago Tribune, October 10, 1984: 47.

53 Bevacqua telephone interview.

54 Bevacqua telephone interview.

55 Vern Plagenhoef, “Bevacqua’s three-run shot kills Tigers, 5-3”, Muskegon Chronicle, October 11, 1984: 31.

56 Dave Distel, “In the finest traditions of World Series, Bevacqua jumps from nobody to hero,” Los Angeles Times, October 11, 1984: 34.

57 Distel, “In the finest traditions of World Series, Bevacqua jumps from nobody to hero.”

58 Dave Distel, “Tiger fans make the day even worse for Padres,” Los Angeles Times, October 15, 1984: 38.

59 Underwood, “A Great Role Player.”

60 Underwood, “A Great Role Player,”

61 Gary Ferman, “Padres’ batter Bevacqua not ready to quit swinging,” Miami Herald, February 3, 1985: 409.

62 Underwood, “A Great Role Player.”

63 Gary Hyvonen, “Padres leave three roster spots open,” North County Times, December 10, 1985: 22.

64 Gary Hyvonen, “Padres give Bevacqua a ‘no’ with an option,” North County Times, January 8, 1986: 21.

65 John Shea, “Few farewells for Bevacqua,” Daily Times-Advocate, March 25, 1986: 17.

66 Steve Beitler, “The empire strikes out: Collusion in Baseball in the 1980s,” SABR, https://sabr.org/journal/article/the-empire-strikes-out-collusion-in-baseball-in-the-1980/(last accessed May 2, 2025).

67 Jeff Barto, “1985 Winter Meetings: Free-Agent Freezeout: Collusion I,: SABR, https://sabr.org/journal/article/1985-winter-meetings-free-agent-freezeout-collusion-i/ (last accessed May 13, 2025).

68 “Baseball Collusion Damages,” USA Today, January 19, 1995: 12.

69 Larry Stewart, “Long, Wide World of ABC Highlighted in a 2-hour special,” Los Angeles Times, April 25, 1986: 55.

70 Strasberg telephone interview.

71 Bevacqua telephone interview.

Full Name

Kurt Anthony Bevacqua

Born

January 23, 1947 at Miami Beach, FL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.