Maple Leaf Stadium (Toronto)

This article was written by Kurt Blumenau

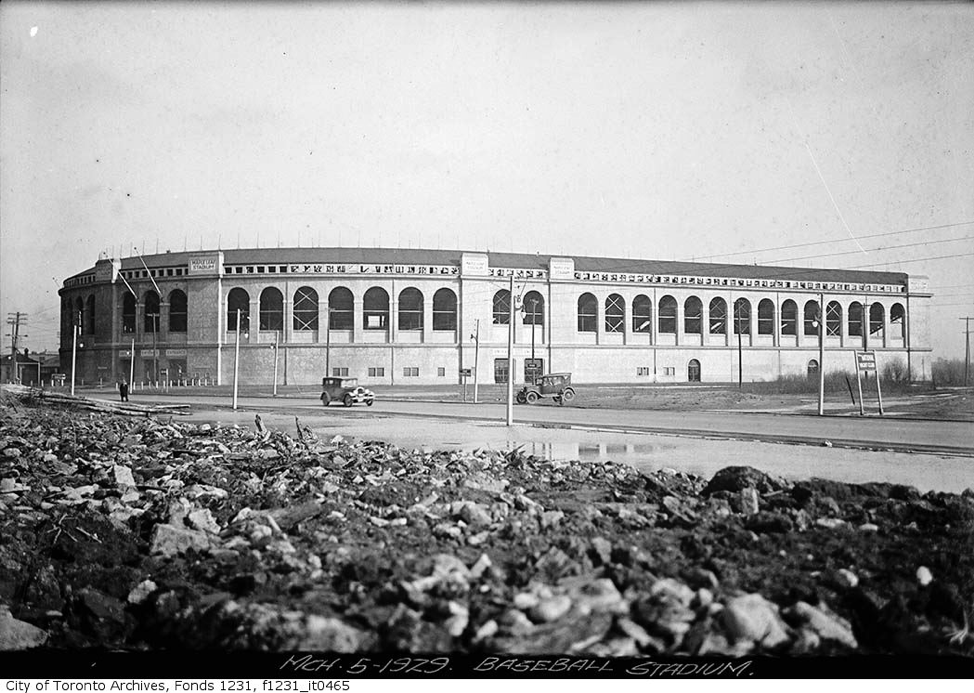

Maple Leaf Stadium, circa 1929. (City of Toronto Archives)

Toronto is a world-class city with a proud baseball history, but its ballparks have not always met a high standard. Exhibition Stadium, the American League Blue Jays’ home from 1977 to 1989, was a converted football stadium whose seating arrangements were not entirely suited to baseball. Its multi-purpose replacement, Rogers Centre, has a retractable roof and artificial turf – adaptations that make practical sense in a cold northern climate, but that fall short of many baseball fans’ aesthetic preferences for green grass and open skies.

The city had a vintage “jewel box”-style ballpark for more than 40 years. If one ambitious Canadian business leader had had his way, Maple Leaf Stadium would have been an American or National League park. Instead, the ballpark played host to minor-league teams from 1926 to 1967, years in which the city’s big-league dreams repeatedly fell short of fruition. Even without big-league ball, the park accommodated four decades’ worth of great games and famous names, hosting an eventful if somewhat faded chapter in Toronto’s baseball and civic history.

The history of professional baseball in Toronto dates to the 1880s, and the city became a charter member of the modern International League in 1912. For years, Toronto ballclubs played at Hanlan’s Point Stadium on Toronto Island, a site accessible only by ferry.

Lawrence “Lol” Solman, a well-liked Toronto businessman, had begun his professional career as manager of the Toronto Ferry Company, which benefited from carrying fans to Hanlan’s Point. In the early ‘20s, Solman – by then an entrepreneur of varied interests – became president of the Toronto Maple Leafs baseball team, which bore that name years before the city’s professional hockey team took it up.1

Despite his link to the ferry, Solman was canny enough to realize that the growth of the automobile created a new opportunity for a ballpark on the mainland. In September 1925, the Toronto Harbour Commission agreed to lease Solman 10 acres of filled-in land at the foot of Bathurst Street for a new stadium.2 Future big-league manager Mayo Smith, a Maple Leafs outfielder in the park’s early years, described the outfield built on reclaimed land as “hard as cement.”3

Designed by the Toronto firm of Chapman & Oxley,4 Maple Leaf Stadium offered a simple and attractive design. A single covered steel-and-concrete grandstand deck enclosed the field, running from one foul pole to the other. No permanent seating was provided beyond the outfield fences.5 (A proposed expansion in 1954-55 would have added two sizable bleacher sections behind much of the outfield, but the expansion was never built.6) A scoreboard and flagpole stood in deep center field.7 Lights were added in 1934, and the Maple Leafs played their first night game at home on June 28 of that year.8

News stories in the late summer of 1925 reported that the new park would seat 30,000 or even 35,000 spectators, which would have made it the largest park in the minor leagues.9 These early reports proved false. As Opening Day approached in April 1926, the stadium’s official capacity was listed at 23,500.10 Over the decades, the park’s available seating declined further; by the mid-1950s, news articles commonly cited capacity of 18,000 to 19,000.11

The smaller capacity made sense from a Triple-A perspective. In a 35,000-seat stadium, the Maple Leafs would have played before vast spreads of empty seats on all but their busiest handful of days. Over time, though, the smaller stadium hamstrung Toronto’s major-league prospects. As struggling teams looked to new markets in the 1950s, the refrain north of the border was the same: Toronto was a major market, but it could not be a real player without a firm commitment to expand its current park or build a new one. New big-league cities like Baltimore and Kansas City made ballpark expansion or rebuilding projects happen. Toronto didn’t until long after Maple Leaf Stadium was gone.12

Construction on Maple Leaf Stadium began in the fall of 1925 and proceeded smoothly, without significant interference from winter weather.13 The park was to have opened April 28, 1926, with Commissioner of Baseball Kenesaw Landis on hand to throw out the first ball.14 But the intended Opening Day was rained out, and Landis was forced to leave town to meet other commitments. Maple Leaf Stadium opened the following day in lingering chill and rain, with about 14,000 fans on hand and Toronto Mayor Thomas Foster throwing the ceremonial first ball. (Landis returned in May 1938 to finally do first-pitch duty in Toronto.15) The Maple Leafs rose to the occasion against the Reading Keystones, scoring five runs in the bottom of the ninth inning and one in the tenth to win 6-5.16

The Maple Leafs made 1926 a season to remember. They posted a 109-57 record, won the IL championship,17 and have been cited as one of the 100 greatest minor-league teams of all time.18 Stars included first baseman Mickey Heath (.335 in 164 games), shortstop Otis Miller (.345 in 152 games), third baseman Billy Mullen (.357 in 134 games) and outfielder Herman Layne (.350 in 148 games). Outfielder Cleo Carlyle had the honor of hitting the first home run at Maple Leaf Stadium on May 3, a shot to deep center field.19

Among the pitchers, Ownie Carroll won 21 games, Lefty Stewart 18, and Jess Doyle and Jim Faulkner 15 apiece. Carl Hubbell, a 23-year-old future Hall of Famer, contributed a relatively modest seven. For all that success, one news report quoted Solman as saying he lost money in 1926 – a foreshadowing of the team’s future.20

The IL introduced the Governor’s Cup playoffs in 1933, and Toronto contended for it intermittently during the Maple Leaf Stadium years. Toronto won the Governor’s Cup playoffs in 1934, 1960, 1965, and 1966 and posted the best regular-season record in 1926, 1943, 1954, 1956, 1957, and 1960.21

One of the most prized events for a baseball fan is the no-hitter, and Maple Leaf Stadium fans didn’t have to wait long to see one. Toronto’s Augie Prudhomme threw the first no-no at the ballpark on August 23, 1927, beating Reading 14-0. Prudhomme threw a second no-hitter almost exactly a year later, beating Jersey City 5-0 in a seven-inning game on August 22, 1928.22

Toronto fans saw 11 no-hitters by home pitchers in the Maple Leaf Stadium era, with Dave Vineyard throwing the last one in the park’s final season on May 23, 1967. They also saw the Maple Leafs get no-hit five times. Visiting pitchers who managed the feat included Tex Carleton, who threw a big-league no-no 11 years after he no-hit the Maple Leafs, and future big-league pitcher, manager, and coach George Bamberger. (For comparison’s sake, at the end of the 2021 season, the Toronto Blue Jays had played 45 seasons – four more than were played at Maple Leaf Stadium – and had hosted only three no-hitters.)23

Maple Leaf Stadium, circa 1961. (City of Toronto Archives)

Pitcher-friendly dimensions might have contributed to the abundance of no-hitters. Early news reports consistently stressed the park’s spaciousness: A visitor in the park’s first few weeks reported that “the playing field is a big one. It takes a real he-man swat to clear either fence for a homer.”24 One game story in 1933 called it a “pitcher’s paradise,” and just 21 homers had been hit there the prior season.25 While the fences were reportedly brought in in 1934, the ballpark’s reputation as a pitcher’s park continued into the 1940s.26 In the early 1950s, Maple Leaf Stadium’s dimensions were quoted at 300 feet to right field, 305 to left, and 425 to center.27 But news reports noted a “sharp fall-away” from the foul poles to the rest of the outfield, requiring a healthy belt for home runs.28

From its earliest days, Maple Leaf Stadium hosted a broad range of events beyond baseball. Circuses, boxing matches, softball, football, lacrosse, and various youth sports all made appearances. Soccer proved especially popular, with European teams – like the Glasgow Rangers in 1928 and Liverpool F.C. in 1946 – drawing 15,000 fans or more.29 Canadian hockey heroes from the NHL’s Toronto Maple Leafs and Montreal Canadiens played a sloppy charity baseball game in 1950 to benefit flood relief in Manitoba.30

The city’s Roman Catholic community gathered for annual rallies that drew 25,000 people, presumably with temporary on-field seating.31 Opera singer Miliza Korjus and conductor Oscar Straus packed the park in 1945, drawing 20,000 for a program of classical music.32 Nineteen years and a generation later, the 1964 Mariposa Folk Festival took place at Maple Leaf Stadium, with performers including native Canadians Buffy Sainte-Marie and Gordon Lightfoot and blues veterans Mississippi John Hurt and Rev. Gary Davis.33

But let’s go back to minor-league baseball in the park’s early years. Events in the global Depression period of the early 1930s had a major impact on Maple Leaf Stadium’s future. Solman died in March 1931 at age 67. While he was not always the most visible member of the team’s management group, Solman’s death robbed the Maple Leafs of a “solid man” at the helm and heightened the team’s struggle for solid financial footing.34

The Leafs’ 1932 attendance was disastrously low, possibly fewer than 50,000 fans.35 They were forced to borrow money from the league and went into receivership that fall, owing taxes of more than $20,000.36 Control of the stadium passed into the hands of the Toronto Harbour Commission.37 In a sign of the straitened economic times, the ballpark – less than a decade old – was advertised for sale at auction in early 1933 and received no bids.38 Maple Leaf Stadium remained under the control of the Harbour Commission for the remainder of its existence.

New ownership was found for the team, and the Maple Leafs managed to carry on uninterrupted as members of the IL. Throughout the Maple Leaf Stadium years, the team bounced from affiliation to affiliation, with some of its most successful years coming as an independent team. The Leafs’ big-league affiliations included the Detroit Tigers (1932-33), Cincinnati Reds (1934-36), Philadelphia A’s (1940-41 and again in 1945-46), Pittsburgh Pirates (1943-44), Boston Red Sox (1947 and again in 1965-67), Philadelphia Phillies (1948-1950), St. Louis Browns (1951-52), Milwaukee Braves (1962-63), and the Braves and Washington Senators (1964).

Maple Leafs teams of the 1930s and ‘40s finished all over the map, from a regular-season championship in 1943 to 100-loss seasons in 1932, 1940, and 1941. Player-manager Ike Boone won the IL Most Valuable Player award in 1934, hitting .372.39 Future Hall of Famers Burleigh Grimes and Tony Lazzeri also managed the team during this period. Lazzeri was booed at Maple Leaf Stadium after the outbreak of World War II, presumably for his Italian surname, although Lazzeri was an American born in San Francisco.40

Perhaps the best story of these years belonged to pitcher Dick Fowler. A Toronto native, Fowler was discovered at a “baseball school” tryout that attracted 150 young Canadian players to Maple Leaf Stadium in July 1937. He pitched for the Maple Leafs in 1940 and 1941, then moved on to a 10-season major-league career that was interrupted by service in World War II. In September 1945, pitching for the Philadelphia A’s, Fowler became the first Canadian to pitch a major-league no-hitter. Scout Clyde Engle, who ran the Leafs’ tryout camp, traveled through Canada and New England to sign future major-leaguers for the Leafs, including Walt Lanfranconi, Frank Colman, and Phil Marchildon.41

Canadian soldiers abroad during World War II missed their home country, including its ballparks. In 1945, the Canadian Press reported on a series of athletic competitions among Canadian Army soldiers stationed in the Netherlands. The soldiers dubbed their recreational facility “Maple Leaf Stadium,” apparently in honor of Toronto’s original.42

The Maple Leafs received a major postwar shakeup in July 1951, when Jack Kent Cooke purchased the team. The energetic owner of newspapers and radio stations, not yet 40 years old, promised Toronto fans “a new deal.”43

He delivered with a string of imaginative promotions that earned comparisons to flamboyant major-league owner Bill Veeck, whose St. Louis Browns happened to be the Maple Leafs’ parent club at the time. In his first few weeks, Cooke handed out free sodas and hot dogs, brought in actress Gloria de Haven and musical comedian Victor Borge for appearances, and hired a pole sitter who planned to stay atop his perch until Toronto reached the first division.44

One scribe tut-tutted Cooke for seeking success through “‘Roman Holiday’ shenanigans” and “evasive hippodrome nonsense,”45 and a proposed on-field wedding in 1954 was canceled amid outraged criticism from city clergy.46 Still, Cooke laughed all the way to the bank, as attendance in 1952 reached a record 469,325.47 He laughed all the way to the podium, too, being honored as The Sporting News’ Minor League Executive of the Year in 1952.48 Another fan-friendly innovation introduced later in the Cooke years was low-alcohol beer, first sold at the ballpark in 1957.49

Cooke made a substantive on-field change by integrating the Maple Leafs, signing Black second baseman Charlie White and pitcher-outfielder Leon Day within two weeks of taking over.50 Day, a future Hall of Famer, pitched in 14 games that season and then moved on to other teams.51 White played 132 games over two seasons before moving on to two seasons with the Milwaukee Braves. White and Day paved the way for future Black Maple Leafs like Sam Jethroe, Earl Battey, Dave Pope, Lou Johnson, Mack Jones, Marshall Bridges, and Reggie Smith – not to mention later generations of Black Blue Jays stars.

On August 18, 1950, less than a year before Cooke’s takeover, the Philadelphia Stars and Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League played a single neutral-site game at the ballpark.52 The Negro American League was one of seven Black leagues that Major League Baseball formally recognized as major leagues in December 2020.53 Major League Baseball specifically limited its period of formal recognition from 1920 to 1948, though, so the game at Maple Leaf Stadium falls slightly outside the period when the Negro leagues are considered major leagues – at least by MLB’s definition.

Traveling Black teams had played at Maple Leaf Stadium since its earliest days. News items from the summer of 1926 mention exhibition games involving the Buffalo Colored Giants and the Pullman Colored Stars of Buffalo.54 Satchel Paige also passed through Maple Leaf Stadium during his days in the Negro Leagues, pitching for the Kansas City Monarchs against the House of David before a crowd of 12,000 in August 1942.55

Cooke made no secret of his desire to bring the big leagues to Toronto – he was linked to attempts to buy several teams – and was keenly aware the city needed a larger stadium. He reportedly tried without success to buy Maple Leaf Stadium from the Harbour Commission to speed its expansion, then offered to build a $6 million stadium elsewhere in Toronto if the city would donate the land. It didn’t.56

Maple Leaf Stadium, circa 1968. (City of Toronto Archives)

In the 1954-55 offseason, Maple Leaf Stadium came as close as it ever would to expansion. Toronto City Council voted in January 1955 to approve, in principle, an enlargement adding 18,000 bleacher seats at a cost of $1.75 million.57 But the plan would have required the Harbour Commission to issue bonds. The commission said no thanks to the financial commitment, telling City Council it would prefer to redevelop the ballpark site for a more profitable commercial use.58

Plans were floated in 1958 to expand Canadian National Exhibition Stadium – the same Exhibition Stadium later used by the Blue Jays – to accommodate both major-league baseball and Canadian Football League play, including the CFL’s showcase Grey Cup championship game.59 The city’s football interests outmaneuvered Cooke, to his disappointment, and the expansion project was planned and executed for football only.60

In 1959, Cooke landed a commitment for one of eight franchises in the Continental League, a planned rival to the AL and NL backed by legendary baseball executive Branch Rickey. The Continental League required stadia of at least 35,000 seats.61 Once again Toronto officials showed no enthusiasm. Mayor Nathan Phillips said the task of creating a suitable facility “looks to me like a chore for the private promoters. I think they’ll know what to do.”62 Frederick Gardner, chairman of the Metropolitan Toronto Council, added: “I hope that in some manner or other [Cooke] will be able to finance the franchise and the other things needed for a major league club.”63 In any event, the Continental League never began play, and Cooke was unable to use it to force the city’s hand on a stadium.

As the drama around Maple Leaf Stadium’s potential major-league future arose and subsided, the ballpark was showing signs of age, despite periodic bursts of investment, including an $80,000 upgrade circa 1950.64 Members of the 1959 Miami Marlins rated Maple Leaf Stadium’s lighting, infield surface, and showers the worst in the IL.65 The Milwaukee Braves agreed, with some players criticizing the lights following a 1958 exhibition game.66 A writer in another IL city called the lights “the worst in the entire International League,” suggesting it was no coincidence that 21 of the Maple Leafs’ team-record 32 shutouts in 1960 were pitched at home.67

It might not have helped matters that some of the park’s staff apparently had other things on their mind besides upkeep. In 1957, Colin Fraser, chief groundskeeper for 22 years, and two other ballpark employees pleaded guilty to charges related to a series of break-ins and thefts at the stadium. Items stolen included cigarettes, mustard, tea, and paint.68

By the mid-1960s, criticism of the old park’s condition grew sharper. In May of 1967, one writer called it an “unloved stepchild” that had “the blank abandoned look of long disuse.”69 (The same writer sharpened his claws in July, calling the ballpark “decrepit” and “an ugly stepdaughter.”70) A series of fires in the park’s later years caused damage. The scoreboard went up in flames in August 1955.71 An apparent arson fire during a furniture auction, held at the ballpark during an off-day in June 1958, caused $10,000 in roof damage.72 Still another fire in the 1963-64 offseason gutted the general manager’s office, destroying team records; repairs were added to an upgrade list that also included painting and new field lights.73 An alert eight-year-old boy passing the stadium in May 1961 spotted and reported a roof fire, helping firefighters prevent potentially significant damage.74

Cooke didn’t stick around until the end. Reportedly frustrated by business dealings in Canada,75 he moved to the United States and sold the team to new majority owners Sam Starr and Bob Hunter in January 1964.76 The boom days of 1951-52 were a distant memory by then, as Cooke reportedly lost $300,000 owning the Maple Leafs.77 Cooke later scratched his big-league itch by owning, at various times, the NFL’s Washington Redskins, the NBA’s Los Angeles Lakers, and the NHL’s Los Angeles Kings, building new facilities for all three.78 He was inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 1985.79

On the field, the Maple Leafs enjoyed a final spurt of glory in the mid-1960s. In its final few seasons, the team was a Boston Red Sox affiliate managed by Dick Williams in his first professional managing assignment.80 Williams’s Leafs finished third in the regular season in 1965 and tied for second in 1966. They won the Governor’s Cup postseason playoffs both years.81 The Boston parent club also paid a visit to Maple Leaf Stadium on June 20, 1966, defeating a team of IL all-stars, 8-4.82

A number of Maple Leafs – such as Reggie Smith, Joe Foy, Mike Andrews, Mike Ryan, Russ Gibson, and Gary Waslewski – joined Williams in Boston in 1967. This Toronto contingent contributed much to the “Impossible Dream” AL champion team that year, which helped end years of underperforming “country club” baseball in Boston and set the Red Sox on a new competitive course.

This success on the field, though, didn’t bring a surge at the gate. Attendance numbers – 144,785 in 1964, 118,310 in 1965, and 96,918 in 196683 – suggested Torontonians had given up on their minor-league team and its aging ballpark. Even the visit by the Red Sox for the exhibition game drew fewer than 2,500 fans, far and away the all-time low in 11 years of IL All-Star exhibitions featuring big-league opponents.84

Perhaps the only population in Toronto that truly loved the ballpark was its starlings. At one point, the Maple Leafs commissioned Dr. Bill Gunn, a Toronto-area recorder of wildlife sounds, to provide the recorded distress call of a starling, which was played over the stadium’s PA system to flush out the birds.85

In 1967, the final edition of the Maple Leafs – propped up by financial support from the Red Sox86 – missed the playoffs, struggling to a 64-75 record under future Boston manager Eddie Kasko. On one sunny, warm “perfect baseball night” in late August, the Leafs drew an official crowd of 627 against the Rochester Red Wings. A sportswriter on hand suggested the actual number might have been half that.87

On September 4, 1967, an officially announced crowd of 802 attended the final baseball game at Maple Leaf Stadium. The Syracuse Chiefs, a New York Yankees farm club, beat Toronto 7-2 behind a complete game by Stan Bahnsen, who earned the AL Rookie of the Year award the following season. Knockabout pitcher Garry Roggenburk started and lost for the Maple Leafs; Billy Rohr, who had electrified Boston fans by throwing a near no-hitter in April, gave up a run in one inning of relief. Toronto second baseman Syd O’Brien ruined Bahnsen’s shutout in the ninth inning by hitting the ballpark’s last home run.88

In mid-October, Starr and Hunter agreed to sell the bankrupt franchise for $65,000 to an Indiana realtor named Walter Dilbeck, who immediately announced plans to move the team to Louisville, Kentucky, for 1968.89 The team had drawn just 92,000 fans in its final season at Maple Leaf Stadium and lost roughly $400,000 in its final four seasons, leaving a string of creditors.90 “Fortunes have been lost and none gained by the numerous financial backers of the Toronto entry,” a Canadian sportswriter summarized that year.91

On a cold, foggy day in December, an auctioneer sold off items left behind at the ballpark, finding takers for a pair of dirt-encrusted home plates ($5 each), 100 bats ($1.15 each), the clubhouse whirlpool bath ($85), and even a pile of crutches ($1). The event drew 160 bidders.92 The Harbour Commission moved quickly to put its white elephant out of its misery, awarding a contract for the stadium’s demolition in February 1968.93 Toronto remained without pro baseball until March 1976, when the expanding AL awarded the city the Blue Jays franchise. The province of Ontario and the city of Toronto, finally willing to invest in big-league facilities, each agreed to contribute $7.5 million toward improvements at Exhibition Stadium, where the new franchise began play on a snowy day in April 1977.94

As of 2022, the former site of Maple Leaf Stadium was home to apartment buildings and a public park, Little Norway Park, that includes a ball field.95 A few high-profile neighborhood landmarks from the Maple Leaf Stadium days still existed at that time, including the former Tip Top Tailors building, since converted to lofts, and the former Canada Malting building. Rogers Centre is only about a mile away – or, to use the appropriate Canadian measure, only about 1.6 kilometers.

Author’s note

This article is dedicated to the memory of Joe Dudziec, a former minor-league ballplayer who was arrested during a game at Maple Leaf Stadium on August 19, 1953, while suffering an apparent mental breakdown. He died of pneumonia a week later in a mental hospital at age 20 and was buried before his parents were notified of his death. The case was briefly a cause célѐbre in Ontario, with both city police and provincial health officials clearing themselves of blame.96

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Rory Costello and David Bilmes and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources and photo credits

The author consulted baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org for background information on players, teams, and seasons.

Photo of Maple Leaf Stadium in 1961 made available through a Creative Commons license by the City of Toronto Archives. Photos of stadium in March 1929 and January 1968 made available without use restrictions by the City of Toronto.

Notes

1 Toronto’s minor-league baseball teams used the Maple Leafs name as far back as 1902. The hockey team we know as the Maple Leafs was founded in 1917 as the Toronto Arenas, then changed its name to the St. Patricks before adopting the Maple Leafs name in 1927. Lol Solman, who built Maple Leaf Stadium, was also part of the group that built Arena Gardens, the hockey team’s first venue. Michael Stainkamp, “A Brief History of the Toronto Maple Leafs,” NHL.com, accessed June 29, 2022; “Lawrence Solman,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, accessed June 29, 2022.

2 “Lawrence Solman,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography; Canadian Press, “Toronto Leafs to Move to Mainland,” Winnipeg (Manitoba) Free Press Evening Bulletin, September 5, 1925: 19; Jamie Bradburn, “Historicist: Opening Day at Maple Leaf Stadium,” Torontoist blog. Posted April 11, 2015; accessed June 29, 2022.

3 Dink Carroll, “Playing the Field,” Montreal Gazette, June 21, 1967: 19. Smith played for the Maple Leafs in 1933, 1935, and 1937 through 1939. He reached the majors for a single season with the Philadelphia A’s in 1945.

4 Entry for Alfred Hirschfelder Chapman, Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada 1800-1950. Accessed June 23, 2022.

5 Several stories reported that a temporary bleacher section seating 1,000 was in place in left field for the park’s opening. One such account is “Toronto Stadium One of the Finest,” Kingston (Ontario) Standard, April 11, 1926: 11.

6 A photo of Maple Leaf Stadium, illustrated with two hand-drawn bleacher sections spanning much of the outfield, appeared in the Brantford (Ontario) Expositor, January 29, 1955: 8.

7 “Toronto Stadium One of the Finest.”

8 “Night Ball in Toronto,” Montreal (Quebec) Gazette, June 23, 1934: 14; “Leafs Get Four Runs in Ninth to Tie Game,” Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, June 28, 1934: 16.

9 Robert C. Stedler, “Bob’s Comment,” Buffalo (New York) Times, August 25, 1925: 13; Canadian Press, “Toronto Leafs to Move to Mainland,” Winnipeg (Manitoba) Free Press Evening Journal, September 5, 1925: 19; “Toronto Stadium Will Seat 30,000,” Montreal (Quebec) Gazette, September 5, 1925: 19.

10 “Toronto Stadium One of the Finest.”

11 A few examples: Photo of ballpark and caption, Brantford Expositor, January 29, 1955: 8; Andy McCutcheon, “Rose and the Red Wings,” Richmond (Virginia) News Leader, July 5, 1954: 18; Gerry Parker (United Press), “Montreal, Toronto Mentioned as Big League Prospects,” Shamokin (Pennsylvania) News-Dispatch, June 30, 1954: 12.

12 Baltimore built Memorial Stadium in 1949-1950 as a single-decked uncovered stadium seating 30,000. To prepare for the arrival of the former St. Louis Browns, an uncovered upper deck was added to bring seating to about 48,000. Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium, built in 1923, was almost entirely rebuilt as a double-decked structure during the 1954-1955 offseason to raise capacity from 17,000 to 31,000 for the incoming A’s, formerly of Philadelphia. Lawrence S. Ritter, Lost Ballparks: A Celebration of Baseball’s Legendary Fields (New York: Viking Studio Books, 1992): 111-120 and 129-139.

13 “Toronto Leafs Await Spring,” Windsor (Ontario) Star, October 23, 1925: 2; “Notes,” Branford Expositor, April 1, 1926: 16. The latter news item reported that a weather delay of a few hours on March 31 was the first delay seen since the start of work on the park.

14 “Landis to Attend,” Kingston Whig-Standard, April 16, 1926: 8.

15 Mort Fellman, “Sport Static,” North Bay (Ontario) Nugget, May 6, 1938: 16.

16 Bradburn.

17 The Maple Leafs’ championship broke a seven-season run by the Baltimore Orioles.

18 Baseball-Reference BR Bullpen pages on the Toronto Maple Leafs and the 100 Greatest Minor League Teams of All Time, accessed June 27, 2022. Historians Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright picked the list of greatest minor-league teams in 2001. From the Maple Leaf Stadium years, the 1960 Maple Leafs, who won the Governor’s Cup playoffs and the regular-season championship, also made the list.

19 “Carlyle Hitting,” Windsor Star, May 4, 1926: 9.

20 “Karpe’s Comment,” Buffalo Evening News, October 27, 1926: 37.

21 Baseball-Reference BR Bullpen pages on the Governor’s Cup and the Toronto Maple Leafs, accessed June 27, 2022.

22 All information on minor-league no-hitters in this and the next paragraph is taken from Baseball-Reference’s page on minor-league no-hitters, accessed June 24, 2022. A linked spreadsheet that listed minor-league no-nos in detail was especially helpful.

23 List of all-time major-league no-hitters on MLB.com (the official site of Major League Baseball), accessed June 24, 2022. The three major-league no-hitters that occurred in Toronto through the end of 2021 were thrown by Dave Stewart of the Oakland A’s on June 29, 1990; Justin Verlander of the Detroit Tigers on May 7, 2011; and Verlander again for the Houston Astros on September 1, 2019. Other no-hitters involving the Blue Jays in this time span were thrown on the road.

24 “Karpe’s Comment,” Buffalo Evening News, May 19, 1926: 31. The columnist also noted that Maple Leaf Stadium’s original press accommodations were below ground and behind home plate, with limited view of the field. An aerial press box similar to those in other parks was later provided.

25 Frank Wakefield, “Homer Drive Gives Leafs 2-1 Victory,” Buffalo (New York) Evening News, September 3, 1932: 6; “Big Struggles Likely to Be Traded by Orioles,” Kingston Whig-Standard, November 5, 1932: 8.

26 “Leafs to Install Lights, Shorten Fences Next Year,” Buffalo Evening News, September 12, 1933: 34; W.G. Curran, “Sports News and Views,” Sault Star (Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario), August 10, 1942: 9.

27 “Canadian Sports Parade,” Kingston Whig-Standard, May 9, 1951: 11. The StatsCrew.com page for Maple Leaf Stadium, accessed June 24, 2022, gives unattributed dimensions of 311-425-310 in 1939 and 300-425-305 in 1961.

28 Shelley Rolfe, “The Fences Close In,” Richmond (Virginia) Times-Dispatch, May 14, 1957: 20. Richmond hosted International League teams from 1954 to 2008. This and other stories make clear that most other IL parks of the period had at least one short fence, and Buffalo’s Offermann Stadium was snug to both right and left fields.

29 Canadian Press, “Big Crowd Sees Liverpool Triumph,” Regina (Saskatchewan) Leader-Post, June 6, 1946: 12; “Soccer Shots,” Branford Expositor, July 10, 1929: 18.

30 Canadian Press, “Toronto Wallops Montreal in Relief Fund Ball Game,” Kingston Whig-Standard, June 12, 1950: 11. Toronto won the game 27-9.

31 Canadian Press, “Toronto Rally of Holy Name Society,” October 5, 1948: 10; and other stories from the post-World War II years about other Holy Name rallies.

32 Jack Gray (Canadian Press), “Oscar Straus, Miliza Korjus Pack Maple Leaf Stadium,” Owen Sound (Ontario) Sun Times, August 1, 1945: 6.

33 List of performers at Setlist.fm, accessed June 24, 2022. Setlist.fm, which collects concert setlist and other information, also lists two rock performances as having taken place at the ballpark. However, contemporary news accounts of the 1966 Herman’s Hermits/The Animals double bill make clear that it occurred at Maple Leaf Gardens, home rink of the Toronto Maple Leafs hockey team, and not Maple Leaf Stadium. The other listed performance, by Canadian band The Guess Who in April 1974, clearly couldn’t have occurred at Maple Leaf Stadium, which had long since been demolished.

34 “Lawrence Solman Is Widely Mourned,” Montreal Gazette, March 25, 1931: 19; Michael J. Rodden, “Sports Highways,” Kingston Whig-Standard, May 23, 1946: 9.

35 One contemporary report gives the season’s attendance at 80,000: “Leafs’ Poor Season,” Montreal Gazette, September 10, 1932: 12. Several later sources cite an attendance figure of 49,963, including Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 3rd edition (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 2007): 329. StatsCrew.com also cites that figure.

36 “Leafs’ Poor Season;” Paul Menton, “A Different President,” Baltimore Sun, November 30, 1932: 22; “Obtains Property,” Montreal Gazette, December 30, 1932: 14.

37 “Obtains Property.”

38 “Leaf Stadium Not Wanted,” Buffalo Evening News, February 3, 1933: 32.

39 Bill Nowlin, “Ike Boone,” SABR Biography Project, accessed June 27, 2022.

40 Dink Carroll, “Playing the Field,” Montreal Gazette, May 8, 1945: 22. Given that Lazzeri’s 1940 Leafs lost 101 games, it’s possible that the fans had other reasons to boo him, but this article attributes it to apparent anti-Italian sentiment.

41 Gary Belleville, “Dick Fowler,” SABR Biography Project, accessed June 27, 2022; Associated Press, “Clyde Engle, Ex-Boston Red Sox Player, Dead,” Windsor Star, December 27, 1939: 2 (sports section).

42 Canadian Press, “Canadian Scottish Take Sports Title,” Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, July 16, 1945: 11.

43 Don Peacock (Canadian Press), “Jack Cooke Buys Baseball Leafs,” North Bay Nugget, July 6, 1951: 15.

44 Canadian Press, “Toronto’s Baseball Leafs Headed for Better Things?” Edmonton (Alberta) Journal, July 17, 1951: 6.

45 Michael J. Rodden, “Sports Highways,” Kingston Whig-Standard, July 19, 1952: 10.

46 “Weddings in Ball Park Said Absolutely Pagan,” Calgary (Alberta) Albertan, June 17, 1954: 5; Canadian Press, “Ball Park Wedding Off in Toronto,” Montreal Gazette, June 18, 1954: 17.

47 Cy Kritzer, “Jack Cooke Settles for 469,325 at Gate,” The Sporting News, September 17, 1952: 27. The Leafs outdrew one major-league team in 1952: The lame-duck Boston Braves drew only 281,278. The StatsCrew.com page for Maple Leaf Stadium lists a slightly smaller attendance number – 446,040. According to StatsCrew, attendance only topped 400,000 in one other year, 1954, when it reached 408,876. Accessed June 24, 2022.

48 “Kings and Queens … of ’52 Sports Competition,” The Sporting News, January 7, 1953: 14.

49 Canadian Press, “Weak Kick Beer Sold at Toronto Baseball Game,” Vancouver Province, June 27, 1957: 24; Canadian Press, “Not Permitted to Market Beer through Groceries,” Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, June 28, 1957: 20.

50 Canadian Press, “Leafs Sign Two Negro Players,” North Bay Nugget, July 16, 1951: 11.

51 According to Baseball-Reference, Day appeared in 20 games with the 1951 Maple Leafs and hit .259. He is not listed as appearing at any other position besides pitcher, so he might have picked up a few at-bats as a pinch-hitter in addition to his pitching duties.

52 “Clowns Sell Hairston to Chicago White Sox,” Macon (Georgia) News, August 7, 1950: 3. The game is also cited in Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals (Phoenix, Arizona: Society for American Baseball Research, 2019): 291.

53 Anthony Castrovince, “MLB Adds Negro Leagues to Official Records,” MLB.com. Posted December 16, 2020; accessed June 24, 2022.

54 Untitled news item, Branford Expositor, June 17, 1926: 3; “Giants and Brands Play at Toronto Saturday,” Buffalo Evening News, August 13, 1926: 17.

55 Canadian Press, “Large Crowd Sees Paige in Toronto,” Kingston Whig-Standard, August 20, 1942: 18. Paige pitched the final three innings of the game.

56 United Press, “Toronto After Veeck’s Club,” Bristol (Virginia) Virginia-Tennesseean, April 29, 1953: 11; Canadian Press, “Dream Realized for Leafs’ Owner,” Regina Leader-Post, July 28, 1959: 25.

57 Canadian Press, “Toronto Council Approves Plan Enlarge Stadium,” Ottawa Journal, February 1, 1955: 15. This story says the additional 18,000 seats would have brought capacity to 42,200 – apparently using the 23,500 seating figure quoted in the earliest days of the ballpark. It seems more likely in retrospect that 18,000 more seats would have roughly doubled capacity to somewhere around 36,000 to 37,000, which still would have been adequate for major-league use.

58 Canadian Press, “Commission Not Anxious Enlarge Stand,” Sault Star, February 10, 1955: 28; Canadian Press, “Plans to Enlarge Leaf Stadium Are Stalled,” Brantford Expositor, February 11, 1955: 8.

59 Bill Senyk (Canadian Press), “Toronto Divided Over Big League Baseball,” Ithaca (New York) Journal, September 19, 1958: 13; Canadian Press, “Baseball, Football Clubs Back All-Purpose Stadium,” Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, January 3, 1958: 10.

60 Canadian Press, “Finishing Touches on CNE Stadium Make It Second Largest in Canada,” Kingston Whig-Standard, July 29, 1959: 11.

61 Associated Press, “Land Requested for Toronto Ball Park,” Fort Myers (Florida) News-Press, July 31, 1959: 3B.

62 “Dream Realized for Leafs’ Owner.”

63 Canadian Press, “New Park if Leafs in Majors,” Ottawa Citizen, July 28, 1959: 1.

64 Canadian Press, “Phyllis Indispensable to Canadian Ball Club,” Vancouver Province, February 26, 1951: 13.

65 Don Hunt, “Marlins’ Defensive Play Puts Them in 4th Place,” Miami News, June 12, 1959: 4C. Players were complaining about Maple Leaf Stadium’s lights at least as early as 1942, when Toronto’s Frank Colman said he couldn’t hit .220 if he played all his games at the park. Dink Carroll, “Playing the Field,” Montreal Gazette, August 15, 1942: 16.

66 George Beahon, “Braves Beat All-Stars; Browning Halts Champs,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, July 29, 1958: 23.

67 George Beahon, “Odds Without Ends,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, September 11, 1960: 2C.

68 Canadian Press, “Stadium Staff Facing Thefts,” Windsor Star, August 7, 1957: 12.

69 Bill Vanderschmidt, “Wings Split with Leafs on Leonhard’s 4-Hitter,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, May 23, 1967: 1D.

70 Bill Vanderschmidt, “IL Baseball in Toronto Near End?” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, July 12, 1967: 3D.

71 Canadian Press, “Fire Destroys Board,” Sault Star, August 4, 1955: 18.

72 Canadian Press, “Fire Threatens Maple Leaf Stadium,” Kingston Whig-Standard, June 6, 1958: 1; “Arson Suspected,” Vancouver (British Columbia) Province, June 7, 1958: 5.

73 Vern Degeer, “Good Morning,” Montreal Gazette, March 4, 1964: 23.

74 Canadian Press, “Alert Boy, 8, Helps Quell Stadium Fire,” Montreal Star, May 8, 1961: 16.

75 Cooke is said to have been offended when the Canadian government rejected his bid for the country’s first privately owned television license in 1960, instead choosing a bid by rival businessman John Bassett. (As owner of the Toronto Argonauts football team, Bassett had also benefited from Toronto’s late-1950s decision to expand Exhibition Stadium for football use only.) Marci McDonald, “The Lion in Winter,” Macleans, January 27, 1992: 40-41.

76 Associated Press, “Cooke Sells Toronto Cut,” Fort Worth (Texas) Star-Telegram, January 21, 1964: 6. New owners Starr and Hunter sold shares in the team to the public.

77 Barbara Moon, “Jack Kent Cooke in Lotusland,” Macleans, July 4, 1964: 14.

78 The Lakers and Kings shared a facility, the Forum, in Inglewood, California. The stadium Cooke built for the Redskins in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., initially carried his name but has since been rebranded for corporate sponsors.

79 “Jack Kent Cooke,” Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum website. Accessed June 24, 2022.

80 Williams, a future Hall of Famer, succeeded another future Hall of Famer who also took his first managing job in Toronto. Sparky Anderson, at age 30, led the 1964 Maple Leafs to an 80-72 record before leaving town for other opportunities. Anderson had played for the Leafs from 1960 through 1963, following a single season in the majors with the Philadelphia Phillies in 1959.

81 Regular-season standings from Baseball-Reference; Governor’s Cup titles from Baseball-Reference BR Bullpen Governor’s Cup page, accessed June 24, 2022.

82 Canadian Press, “Red Sox Trim IL All-Stars by 8-4 Score,” North Bay Nugget, June 21, 1966: 10.

83 Attendance figures taken from the StatsCrew.com page for Maple Leaf Stadium, accessed June 29, 2022. While the attendance numbers given by StatsCrew sometimes differ slightly from those in contemporary news reports – one example is cited in endnote 85 – the difference is not significant.

84 “Red Sox Trim IL All-Stars by 8-4 Score.”

85 “Songs and Sounds of the Forest in Hi-Fi,” Ottawa Citizen (Weekend magazine section), September 17, 1960: 6. The starling anecdote appears on page 46 of the magazine.

86 John M. Flynn, “The Referee’s Sporting Chat,” Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), May 6, 1967: 19.

87 Bill Vanderschmidt, “Red Wings Top Leafs, Gain No Ground,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 26, 1967: 1D.

88 Canadian Press, “Chiefs Defeat Toronto, 7-2, in Season Finale,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, September 5, 1967: 4D.

89 Billy Reed, “Baseball’s Back! Colonels in AAA International Loop,” Louisville (Kentucky) Courier-Journal, October 19, 1967: B9. The Red Sox’ Triple-A team remained in Louisville through the 1972 season, then moved to Pawtucket, Rhode Island, where it spent more than 45 seasons. As of 2022, Boston’s top affiliate plays in Worcester, Massachusetts. Walter Dilbeck, meanwhile, also gained media attention as the backer of another proposed third major league, the “Global Baseball League.” Warren Corbett’s article “A Global Fiasco: Walter Dilbeck’s Third Major League,” published in SABR’s spring 2020 Baseball Research Journal, is heartily recommended.

90 Neil MacCarl, “Creditor Files Bankruptcy Suit Against Toronto,” The Sporting News, December 9, 1967: 46. The StatsCrew.com page for Maple Leaf Stadium, accessed June 24, 2022, lists attendance for the final season as 94,308.

91 Mike Rodden, “Sports Highways,” Kingston Whig-Standard, May 30, 1967: 11.

92 Neil MacCarl, “Leaf Relics Sold for Top Prices at Final Auction,” The Sporting News, January 13, 1968: 45; Canadian Press, “Baseball Leafs Laid to Rest by Auctioneer,” North Bay Nugget, December 19, 1967: 14.

93 Canadian Press, “Toronto Axes Ball Stadium,” Montreal Star, February 17, 1968: 20.

94 Adrian Fung, “April 7, 1977: A Snowy Beginning for Toronto’s Major-League Debut,” SABR Games Project. Accessed June 24, 2022.

95 Nicole Brockbank, “The Original Maple Leafs: Pro-Baseball in Toronto Before the Blue Jays,” CBC News, October 14, 2016. Accessed June 24, 2022.

96 Canadian Press, “Father Reports Son Died, Was Buried Like Dog,” Branford Expositor, September 2, 1953: 3; “Toronto Police Probe Death, Quick Burial,” Victoria (British Columbia) Daily Times, September 2, 1953: 2; Canadian Press, “Exonerate Toronto Police in Man’s Death,” Ottawa Citizen, September 4, 1953: 9; Canadian Press, “Ask Full Report on Man’s Death in Mental Home,” North Bay Nugget, September 9, 1953: 5; “Need Full Report on Death of Joseph Dudziac [sic],” Owen Sound Sun-Times, September 11, 1953: 6; Canadian Press, “Abbreviated Address Sent,” Windsor Star, September 11, 1953: 28. Baseball-Reference lists a Joe Dudziec as playing 36 games in 1953 with the St. Louis Browns’ Class D farm team in Dothan, Alabama. Early-season game stories from the Dothan Eagle newspaper spell the player’s last name Dudziac and do not specify when he left the team or what happened to him afterward. A statistical roundup published on June 2 credits him with 30 games played, while an end-of-season roundup in December credits him with 36, so it’s possible that his career ended sometime in June.