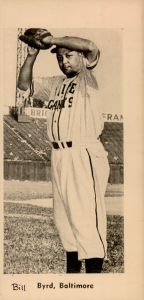

Bill Byrd

“I had a gift. That’s about all there was to it.” – Bill Byrd1

A Negro League ballplayer had no greater testimonial to his individual play than selection to the annual East-West All-Star Game. Of those who were pitchers, only three appeared in seven or more games. Leon Day led the way with nine, followed by Hilton Smith with seven. Bill Byrd also pitched in seven and was selected for two more games, one of which he appeared in as a pinch-hitter and the other in which he was not called on to play. Day and Smith are Baseball Hall of Famers. However, while devotees of Black baseball of the day knew how good Byrd was, playing outside the limelight of the showcase teams in the Negro Leagues has obscured his greatness. The fact is that Byrd’s career certainly showed him to be Hall of Fame-worthy as well, and his story underscores that claim.

A Negro League ballplayer had no greater testimonial to his individual play than selection to the annual East-West All-Star Game. Of those who were pitchers, only three appeared in seven or more games. Leon Day led the way with nine, followed by Hilton Smith with seven. Bill Byrd also pitched in seven and was selected for two more games, one of which he appeared in as a pinch-hitter and the other in which he was not called on to play. Day and Smith are Baseball Hall of Famers. However, while devotees of Black baseball of the day knew how good Byrd was, playing outside the limelight of the showcase teams in the Negro Leagues has obscured his greatness. The fact is that Byrd’s career certainly showed him to be Hall of Fame-worthy as well, and his story underscores that claim.

The Byrd family was a part of the Great Migration, living in Canton, Georgia, where William was born on July 15, 1907, and then relocating to Columbus, Ohio, for a better life when he was 12 years old. Not much is known about Byrd’s parents, Robert and Ovelle (Blake). Byrd himself completed the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s player profile form in 1973 and listed eight years of elementary education in both Canton, Georgia, and Riley, Alabama (the latter an apparent way station for the Byrd family on their way to Ohio).2 Byrd lists no high school in Ohio, but a later newspaper reference ties him to East High School in Columbus.3

Byrd later reminisced about his love for baseball as a kid. “I never had training, never had a teacher,” he told historian John Holway.4 Another biography of Byrd sheds light on his youthful penchant for the game: “According to legend, Bill honed his baseball skills by throwing rocks and hitting rocks with a tree limb that he had fashioned into a baseball bat.5 Simply put, his development as a ballplayer came on the sandlots.

Byrd’s connection to Columbus gave him exposure to the higher levels of Black baseball. Byrd played on a team called the Columbus Turfs in 1932, a member of the Negro Southern League. In his history of the NSL, William J. Plott noted:

The Columbus Turf Team was announced as a new league member in early July. The Ohio team was to play its first game on Saturday, July 16, at Neil Park [in Columbus], the home of the city’s white American Association Team. … It was reported that the Turf Club, sometimes called the Turf Stars, was bringing “colored professional baseball to Columbus” for the first time in ten years.6

Some of the players on the roster that season alongside Byrd were Satchel Paige, Dennis Gilchrist, C.B. “Clarence” Griffin, John Kerner, Alphonso “Duke” Lattimore, Sam Warmack, and Roy Williams; however, actual box scores have not yet been found.7

The Turfs’ play in the NSL may offer insight into how Byrd eventually became known to Tom Wilson, owner of the Nashville Elite Giants, the franchise for which Byrd would play nearly all of his career.

The Elite Giants are very much the story of Wilson, their founder and longtime owner. Wilson was born in Atlanta in the late 1880s. (His birth year is disputed.) His family moved to Nashville to further their education and became doctors. Because of their successful careers, the Wilsons became part of the Black middle class, from which the young Wilson benefited in terms of the social standing and financial wherewithal that came with it.8 Wilson’s business acumen and entrepreneurial pursuits included baseball, and he formed the Nashville Standard Giants in 1920.

Plott’s history of the NSL lists a team called the Nashville White Sox as a charter member of the league in 1920, run and managed by Marshall Garrett, one of Wilson’s business partners. In 1921 the Nashville franchise became the Elite Giants, previously Wilson’s Standard Giants. The NSL struggled early to find its footing. After its first four seasons, the league suspended play in 1924 and 1925, and again in 1928 and 1930. Through 1931, when the league did operate, Nashville won the title four times. In 1930 Wilson orchestrated the Elite Giants’ elevation to the top-tier Negro National League. That team, however, struggled at the gate and finished poorly, and Wilson, always looking for a more viable financial setting, relocated the team north to Cleveland as the Cubs in 1931. A history of “Black Baseball in Depression Cleveland” noted that “Wilson more than likely moved his club from Nashville to Cleveland in an attempt to make a profit off the black population in Cleveland by way of the numbers game.”9 Although this might have been true, the larger African American population in Cleveland in 1930 was probably greater justification for the relocation (72,000 in Cleveland vs. 43,200 in Nashville, providing a bigger population to draw on for Elite games.)10

With the demise of the first, Rube Foster-founded NNL in 1931, the NSL ascended to “major” league status as the only premier Black Ball league left standing at the time. Wilson brought the team back to Nashville for the 1932 NSL season, and his squad, which won the league’s second-half championship, participated in the so-called Dixie Series against the first-half champion Chicago American Giants. The American Giants prevailed over Nashville in seven games. The Elite Giants remained in the NSL for two more years, but with the ongoing economic uncertainty at the height of the Depression, Wilson moved the franchise again. At first, he took his team to Detroit11 in 1935 to join the new Negro National League II (NNL2). However, after he was unable to arrange a lease on Hamtramck Field, he abruptly relocated to greener pastures in Columbus early that season.

Meanwhile, after his stint with the Turfs in 1932, the now 25-year-old Byrd surfaced on Columbus’s first entry in the NNL2 in the league’s 1933 inaugural year. The Blue Birds12 had been one of five affiliate teams in 1931, the last season of the first NNL, and now were a charter member of the reconstituted NNL2. However, the franchise struggled, so Gus Greenlee, president of the league, “moved the Columbus ball club to Cleveland [as the Giants] in hopes of making a profit.”13 A comparison of the rosters of both teams shows several of the Blue Birds making the move to Cleveland.

Records for Byrd in 1933 list 13 appearances as a pitcher with the Blue Birds (including 11 starts with a 3-8 record), but no records are available with him on the Cleveland squad that finished the season and then folded.

Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe and Roosevelt Davis were Byrd’s teammates on the 1933 Blue Birds, and Byrd credited Davis with teaching him how to throw the spitter.14 Byrd bounced around Depression baseball in his early professional years, and “[a]fter the Blue Birds folded that autumn, he went to the last place Cleveland Red Sox.”15 In 1934 the NNL2 tried to resuscitate a presence in Cleveland under what might have been league-appointed ownership of Prentice Byrd (no relation to Bill Byrd) and Dr. E.L. Langrum. The new owners hired Negro League veteran Bobby Williams as manager.16

The migration of Blue Birds/Giants players to the new Red Sox team saw Byrd joining “several of his Blue Bird teammates (Ameal Brooks, Roosevelt Davis, Kermit Dial, Dennis Gilchrist, Clarence Griffin, Wilson “Frog” Redus, and Roy Williams) on the new team.17 The second iteration of Cleveland’s entry in the league fared as poorly as the Cleveland Giants had, and it too was one and done in the league after playing to a 3-22 record. Byrd’s 2-8 record for the NNL’s cellar-dwelling team, along with an ERA of 6.90, was lackluster at best, but his adopted hometown of Columbus offered him another shot in 1935 with the arrival of the Elite Giants from Nashville via Detroit.

It is uncertain whether Wilson and his protégés remembered Byrd from the 1932 NSL season, but his modest beginning with the Columbus Elite Giants in 1935, in which he played alongside a reasonably stable lineup from the prior year, offered a foundation for his future success with that itinerant franchise.

And itinerant they continued to be, playing only one year in Columbus. In 1936 Wilson moved the team again, this time to Washington, DC, having arranged a deal with Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith to lease Griffith Stadium for the Elite Giants’ use. Manager Candy Jim Taylor, in a guest column for the Pittsburgh Courier in the spring of 1936, captured the move:

The Nashville Elite Giants, to be known as the Washington Elites for the 1936 season, started training Saturday. … Tom Wilson, owner of the Elite Giants, has been in baseball for about 20 years and for the last few years his club has been in the Negro National League. He promised Washington fans the same kind of club that he has put on the field in the last few years, and from the looks of things now it will be a first division club. … The pitching staff looks to be the best in the league. Bob Griffith, the schoolboy wonder heads the staff. Andy] Porter the speed ball wonder, sick most of last season, is reported to be in fine shape, Byrd, the big side arm boy from Columbus, Jim Willis, the only veteran on the staff, seems to be ready for a great season. Tom] Glover, southpaw with the club for a while last year will be back. Of the new men, Red Howard, from Memphis … will round out the rotation. Biz Mackey, the old warhorse … will be number one man behind the bat with his ability to handle pitchers.18

Having been promised a first-division team, Washington fans witnessed a slow start by the Elite Giants, but the team won the second-half crown, only to lose to the Pittsburgh Crawfords in the playoffs. Byrd, Jim Willis, and Bob Griffith anchored the Elite Giants’ rotation, with Byrd tossing the most innings and finishing with a 9-4 record and a 3.38 ERA. The other members of Taylor’s pitching staff did not fare as well (the team’s ERA was a voluminous 4.88), and the Washington squad did not play .500 ball.

The Elite Giants reprised their time in Washington with a second season in 1937. Managed now by Mackey, Washington finished 23-36 in league play, a distant fifth to the champion Homestead Grays. Byrd had three batterymates – Mackey, Nish Williams, and 15-year-old Roy Campanella. Records for the year show that Byrd regressed on the mound. The team’s two subpar years in Washington did not do much to build fan support or a financial grounding for the team and it was no surprise that Wilson found justification to relocate once again. In fact, the team played some of its schedule at Oriole Park in Baltimore after Wilson was unable to reach an agreement with Griffith on hosting a full slate of games at Griffith Stadium. In early 1938 the Baltimore Afro-American reported:

It is almost a certainty that the Elite Giants, for the last two years representatives of Washington, DC, in the Negro National League, will be transferred to Baltimore this season. [According to Tom Wilson, Elite Giants owner] “Only a slight hitch remains to be ironed out [regarding stadium usage]. … Last year we lost money from operating from Washington. I sincerely feel Baltimore far superior to Washington as a baseball town. … It has been a long time since Baltimore has had a regular league team and I feel the people there need one and will support one.”19

Wilson and his partners “at last found adequate community support” in Baltimore.20 The city had a sizable African American population (growing from 142,000 in 1930 to 225,000 in 1950 and to nearly a third of the population). The team’s ballpark (Bugle Field) was situated in an East Baltimore working-class neighborhood, not far from the Old West neighborhood in the west-central part of town that middle-class Blacks called home.21 According to Luke, “Baltimore, with its large and growing black population and large black middle class, was just the kind of city Wilson needed for his baseball team.”22

The now Baltimore Elite Giants performed promisingly in their new setting. Managed by George Scales, Baltimore finished third, well behind the Grays and Philadelphia Stars. There was some debate about the final standings, but this was often the case as the NNL2 had limited resources to maintain accurate records. Baltimore assembled a core team that year with players who populated the roster over the next few years: a pitching rotation of Byrd, Andy Porter, School Boy Griffith, and Jonas Gaines; a lineup with veterans Henry Kimbo, Burnis “Wild Bill” Wright, and Bill Hoskins in the outfield; James West, Sammy Hughes, Felton Snow, and Hoss Walker in the infield; and the tandem of veteran Mackey and the young Campanella behind the plate. Despite finishing well behind league-leading Homestead with its future Hall of Famers Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, and Ray Brown, “Tom Wilson decided to keep the Elites in Baltimore. The box office had been good to him even if the team’s won-loss record had disappointed.”23

The 1939 season finally put the Elites on the Black baseball map. The team returned substantially the same lineup as in 1938, but with Felton Snow as manager and Andy Porter and School Boy Griffith having left for Mexico. Midseason pickup Pee Wee Butts was a plus and the rotation of Byrd, Gaines, Willie Hubert, Emery Adams, and Tom Glover was good enough to keep the team competitive. It was an atypical year for the league as the first- and second-half champion Grays and Elites did not play in a championship series. Instead, the top four teams engaged in a playoff. After the Grays defeated Philadelphia and Baltimore survived Newark, the winners played a five-game series. Byrd, the team’s regular-season workhorse with the most wins, won Game Four of the series with the Grays despite giving up 15 hits (including three singles and a homer to Josh Gibson) in a 10-5 outcome that tied the series at two games apiece and set the stage for the winner-take-all Game Five. Baltimore won the game, 2-0, behind the pitching of Gaines and Hubert.24 The Baltimore Afro-American averred, “Climaxing an uphill campaign in a blaze of glory, the Baltimore Elite Giants won the Negro National League baseball championship … by turning back the Homestead Grays.”25

Except for a one-year sojourn to Venezuela, Byrd centered his offseason play in a single Caribbean destination, Puerto Rico. Byrd journeyed to Puerto Rico for three successive winters (1939-1940, 1940-1941, and 1941-1942). The Puerto Rico Winter League had been inaugurated the year before Byrd’s first appearance and became what now is “the longest continually running winter league in the Western Hemisphere.”26 Each owner in the six-team league was “determined to win the all-important inaugural winter league championship, and they set about to staff their rosters with the best players they could find. There was a flurry of activity over the summer of 1938 as the owners went on a recruiting campaign from New York to Caracas, with briefcases full of money.”27 And Negro League ballplayers were prime recruits. Despite competition from Cuba, with its longstanding winter play, “the owners were able to attract several Negro Leaguers to their first season, including George Scales, Dick Seay, Jimmy Crutchfield,” and others. 28

The Puerto Rico Winter League’s success in its first year led to a more lucrative recruitment of Negro League ballplayers in 1939-1940. Signings included Satchel Paige, Ray Brown, Leon Day, Josh Gibson, Dick Seay, Roy Partlow, and Bill Byrd.29 How Byrd surfaced in Puerto Rico is unclear, but the Negro League fraternity was such that those signed in Puerto Rico often informed their team owners about other players to consider for their squads. Byrd ended up on Santurce that winter with fellow Negro Leaguers Josh Gibson, who managed the team, and Dick Seay.30

Byrd tossed a blistering 229 innings in the league his first year and pitched to a record of 15-10 record with a 1.97 ERA.31 Santurce finished at 26-29, with Byrd starting nearly half of the Crabbers’ games, and finished fourth in the eight-team league.32

January 7, 1940, marked a game for the ages between two Negro League hurlers battling under Caribbean skies. Leon Day, pitching for Aguadilla, was Byrd’s mound opponent. Aguadilla scored one run in the first and Santurce countered with one in the fourth. Then “Byrd and Day settled down to a long Sunday afternoon in the sun. The goose eggs piled up inning after inning until the sun set in the west and the umpire called the game on account of darkness. The final score of the 18-inning game was 1-1, and Leon Day had struck out 19 batters over the course of the day.”33

The financial attraction of Puerto Rico, Mexico, and Venezuela in these years was compounded by the inability of the Negro National and American Leagues to pay their players well and “to standardize and enforce the contracts and agreements between owner and player which were often easily broken at the convenience of either party.”34 The difference in wages between the Negro Leagues and the Caribbean was a big deal. Ed Harris of the Philadelphia Tribune “viewed player jumps as inevitable, as some players were not even ‘getting the wages they would on WPA [Works Progress Administration].’”35 Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier noted that “[b]all players are always going to go where they make the most money. Right now, Mexico [and Puerto Rico] is the place. Efforts to stop this have been unsuccessful and will be until the moguls here get together and organize a league with a solid foundation.”36 Chester Washington, also of the Courier, noted “that in this so-called Land of Opportunity how tragic it was that the greatest home run hitter in the game today – Josh Gibson – had to leave his native America to make a lucrative living in far-away Venezuela just because the Negro League can’t afford to pay him the salary he’s worth and the major leagues bar him because he is black.”37

Immediately after his time in the Puerto Rican Winter League in 1939-1940, Byrd was enticed to play for Venezuela’s Centauros de Maracaibo. Records for the 13-15-game season that spring are sparse, but it is known that Josh Gibson, Luis Aparico Sr., and Pedro “Perucho” Cepeda also played for the Centauros. Other Negro Leaguers were lured to Venezuela, including Satchel Paige, Ray Dandridge, and Leon Day. Apparently, Byrd’s time in Venezuela also served as a honeymoon for him and his new wife, Hazel, as they both embarked upon a second marriage.38

When Bill Byrd returned to the United States after his time in Venezuela, he was asked why he had chosen to go to South America to play ball. He responded, “They treat you better down there. They pay your way down. Get you an apartment and pay you pretty well. … They roll out the red carpet for you.”39 This was a common reaction. As Negro League historian Leslie Heaphy has noted, “Whether the Negro League players traveled south during the summer or winter they went because baseball was popular, they loved the game, they needed the extra money, and Latin American fans looked up them as heroes.”40

The increasing exodus of many star players to Puerto Rico and Mexico led to a ban issued by Negro League owners in 1940:

Aware of the potential for disaster during 1940, the two league presidents [J.B. Martin (NAL) and Tom Wilson (NNL)] agreed that any player jumping to a foreign locale would be suspended for three years, and all league clubs would be barred from playing independent teams using or competing against the suspended players.41

El Maestro,42 as Byrd was called in Puerto Rico, had to pitch in the Winter League without his spitter, his bread-and-butter pitch. It was outlawed. Gene Benson, a fellow Negro Leaguer and Byrd’s occasional winter season roommate, remarked to Holway that without the spitter, “I didn’t see no difference. He still blinded us – he threw the ball right past us. He had everything else he needed: threw a hard, good curveball. Shoot, very few teams beat Bill.”43 Even so, Buck Leonard remarked that Byrd would occasionally try to get away with throwing it: “Byrd was cutting heads right and left with that spitter. … Byrd would throw a high pitch over the batter’s head and while everyone watched the ball, Bill hastily put his fingers to his mouth.”44

Much is made of the 6-foot-1 right-hander as a spitballer. According to Luke, “Byrd chewed slippery elm; a soft greenish bark, to help his ball do tricks.45 However, Byrd recounted to Holway:

I threw almost everything: knuckler, slow knuckler, fast knuckler, curve, slider. I had good control … a good fastball overhand. I’d get a guy set up and then throw it. … [And Byrd insisted] I hated the spitter … they made me throw it. … [Candy Jim Taylor told him] if you’re gonna throw it, fake it.” The fear that Byrd might use his spitter … made his other pitches more effective.46

Since Byrd had been banned by the NNL2, Baltimore was without his talents in 1940,47 but the Elites managed to finish second, 3½ games behind the Homestead Grays in the six-team league. Meanwhile, Byrd made his way back to Puerto Rico for a second season, this time with Caguas. The Caguas owners broke the bank that winter to sign Negro League talent, and their investment paid dividends. Caguas won the first-half championship and Santurce the second half to set the stage for a seven-game championship series that ended up being a back-and-forth affair. Byrd lost 1-0 to Santurce’s Ray Brown in Game One, but Caguas won Game Two. A week later, Byrd beat Brown and then Santurce took Game Four. When the series resumed several days later, Byrd was again on the short end of a duel with Brown in Game Five, but Roy Campanella bailed out Caguas to take Game Six the next day. Game Seven immediately followed Game Six and Byrd and Brown dueled for a third time. In the finale Byrd turned in a 6-2 complete-game win to capture the series for Caguas.48

The presence of Byrd and his peers in Puerto Rico and Mexico adversely impacted the NNL2 and NAL, which missed many of their marquee players in 1940. By early 1941, the owners reconsidered their position to ban players who journeyed south, and according to the New York Age:

The] … smart play the owners made was lifting the ban imposed on star players who had “jumped” the country for more lucrative jobs in Mexico, Porto Rico, and Venezuela. These players, whose ranks include some of the biggest names in Negro baseball, will now be allowed to return to the league upon payment of a $100 fine. Since nearly all the team owners are thirsting for the return of such drawing cards as Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige, they will probably be willing to pay the fines for the players of their choice.49

For the Baltimore Elite Giants, despite a decent 1940 season, getting Byrd back (he agreed to pay the $100 fine imposed by the league) made a difference as the Grays and Elites outpaced the rest of the NNL2 in 1941.50

Byrd played one more year in Puerto Rico, 1941-1942, again for Caguas. The team could not repeat its 1940-1941 championship season and finished tied for fifth despite Byrd’s 10 wins. His Puerto Rican swan song ended with his selection to the league’s North All-Star team, his second all-star designation after similar recognition the year before.51

Byrd’s return to the NNL2 after his one-year ban was a remarkable one. Deservedly chosen for that year’s All-Star Game, he compiled a 9-3 record with an ERA of 2.23 against league competition. The Elites lost the first-half pennant to their nemesis, the Grays. Although Baltimore finished ahead of Homestead in the second half, the team now trailed the New York Cubans and missed out on the playoffs. Byrd’s batterymate, Roy Campanella, had a breakout year for Baltimore that provided a hint of things to come in his career. Byrd’s season was punctuated by a 3-2 win against the Memphis Red Sox in July in which he threw no-hit ball through the first eight innings and, purportedly, a three-strikeout “immaculate inning” in the third, fanning the three Red Sox batters he faced with the minimum nine pitches.52

In what was a recurring theme in the 1940s, the Grays again bested the second-place Elite Giants in 1942. Over the next five years, from 1943 to 1947, Baltimore finished fifth, fourth, third, second, and fourth, well behind perennial pennant winners Homestead, and then Newark in 1946 and the New York Cubans in 1947. During those years, Byrd toiled in workmanlike fashion for the Elites, in a rotation that variously included Andy Porter, Jonas Gaines, Tom Glover, Bill Harvey, Bill Burns, and a young Joe Black.

In 1942 Byrd famously beaned Newark Eagles player-manager Willie Wells. The Pittsburgh Courier wrote:

The Jersey team had some … bad luck in the eighth when their player manager Willie Wells, was struck in the temple by a pitched ball from the hand of Bill Byrd, who relieved Porter on the mound. Wells suffered a slight concussion, but soon regained consciousness in the dressing room.53

The story is worth recounting because the incident allegedly led to Wells visiting a local construction site before his next game to obtain and modify a hard hat for use when batting.54 Thus, Wells became the first Negro League player to use a batting helmet.

Ironically, one of Byrd’s worst years in that stretch was 1944, the year in which he was chosen for both All-Star games. In 1945 Wild Bill Wright returned from his extended time in Mexico and along with Henry Kimbro, Roy Campanella, Bill Hoskins, and Norman “Bobby” Robinson, made for a solid lineup, with the team finishing second in league batting.

Even in his later 30s, Byrd still had gas in the tank. His league win totals from 1942 to 1947 were 10, 10, 6, 11, 4, and 8. With NNL2 play amounting to around 60 games per season, Byrd’s career totals, if adjusted to a 162-game schedule, would have averaged 19 to 20 wins per season.

Negro League all-star teams commonly barnstormed against White teams after the regular season ended. In fact, “the Black and White all-stars met regularly in Baltimore [and elsewhere] to make some extra money barnstorming every Friday and Sunday until the weather got too cold. ‘We had a good draw, white and black [Byrd said]. We all had a good time, no arguments, no fussing, nothing like that. Just nice baseball, friendly. I enjoyed playing them.’”55 In 1945 Byrd played for Mackey’s All-Stars in a five-game series against the White Charlie Dressen’s All-Stars. The latter included the likes of Ralph Branca, Virgil Trucks, Red Barrett, and Eddie Stanky. Alongside Byrd were Don Newcombe, Roy Partlow, Monte Irvin, Roy Campanella, Johnny Davis, and Willie Wells.56

In 1947 the breaking of the color barrier was the beginning of the end for the Negro Leagues. “Official” statistics from the Howe News Bureau are available for numerous seasons after 1948, but cannot be fully corroborated by box scores. A new problem arose in that “players like Bill Byrd and Henry Kimbro were two of the many Negro League players who were considered to be too old to be viable candidates to be signed by ‘organized’ baseball. Byrd and Kimbro’s decision was real easy – return to the Baltimore Elite Giants because they didn’t have any other real options.”57 Byrd pitched well for Baltimore in 1947,58 a season marked by Tom Wilson’s death and the transfer of Elite Giants ownership to Vernon Green. Bob Romby was the ace of the staff and, along with Byrd, the rotation included Jonas Gaines, Amos Watson, and Joe Black. Kimbro was the league’s premier hitter. Baltimore finished in third place behind the New York Cubans and Newark Eagles.

Byrd was 10-4 with a 1.75 ERA in NNL2 games in 1948, belying his 40 years. Baltimore won the first-half championship in the last year of the NNL2 but lost to second-half Homestead for a chance to play NAL winner Birmingham in the final Negro League World Series. In the best-of-five series with the Grays, Elites manager Hoss Walker opted to open with Lefty Gaines over Byrd. Gaines lasted 3⅔ innings, giving up five runs in the eventual 6-0 defeat to Homestead. Byrd pitched 5⅓ innings to mop up the game, giving up three hits and a single tally in the top of the ninth. Two days later, on September 16, the Grays captured Game Two – also at Bugle Field – by a 6-2 score, with Joe Black taking the loss for the Elites. The two teams played to a 4-4 tie in Game Three the next day; the game was suspended because of Baltimore’s 11:15 P.M. curfew. Byrd came back two days later to pitch a complete-game 11-3 win. However, the league subsequently declared the 4-4 game to be a forfeit by Baltimore since the team had used stalling tactics in the ninth inning that were intended to ensure that any Grays tallies in that inning would not be counted. The forfeit gave the Grays the series.59

The 1949 season offered the shrinking Negro League fan base glimpses of the Byrd of yesteryear as he pitched to a 12-3 record with a 3.50 ERA.60 The Elites were now a member franchise of the NAL as the NNL2 had folded after the 1948 season. Baltimore won the second-half championship and played the first-half champion Chicago American Giants for the league crown. Baltimore swept Chicago in four games, with Byrd starting Game One and pitching a 9-1 win.61

Byrd’s final year, 1950, saw him play sparingly for the Elites. The organized Black leagues were slowly imploding with fan interest moving to the American and National Leagues and their minor-league systems, which now incorporated the next generation of Black ballplayers. Not long into the season, Baltimore’s owner Richard Powell (now in charge after Vernon Green’s death) released Byrd, who for the rest of the season became player-manager for an independent team in Baltimore, the Negro League All Stars.62

Toward the end of his career, Byrd showed up in a few box scores for other teams, notably the Philadelphia Stars. Why Byrd was with the Stars in June 1944 on the winning end of a 13-0, three-hit, seven-strikeout complete game against the NAL Cincinnati Clowns is uncertain. The Philadelphia Inquirer referenced Byrd in the story “as a right hander from the Baltimore Elite Giants.”63

Byrd was selected for the East-West All-Star Classic nine times, pitching in seven, pinch-hitting in one, and appearing on the roster in another. He first appeared in 1936 (August 23 in Chicago’s Comiskey Park) as a Washington Elite Giant, pitching the middle three innings in a winning cause for the East, 10-2, striking out four and giving up an unearned run.

Byrd was selected for and started both games in 1939, a testimony to his superlative season for Baltimore. In Game One in Chicago (August 6), he pitched three innings with a strikeout, a walk, and two hits allowed. He left the game with a 2-0 lead, but Roy Partlow gave up three runs in the late innings as the East lost the game 4-2. Three weeks later at Yankee Stadium (August 27), Byrd gave up a run in three innings and left the game ahead, 5-1, in a game that the East won, 10-2.

Byrd missed out on the 1940 all-star game due to the ban on players who had started the season in Venezuela. In 1941 he pitched a scoreless ninth as the East won, 8-3, at Comiskey Park on July 27. In 1942 the Cleveland Call Post listed the East and West rosters, noting four Elite Giants: Gaines, Byrd, Kimbro, and Wright. Only Wright and Gaines entered the game.64

In 1944’s August 13 contest in Chicago, Byrd shut out the West in his two innings pitched (the eighth and ninth) but it was mop-up duty as the East lost, 7-4. In 1945 Byrd pinch-hit for the Grays’ Roy Welmaker in the ninth, was walked by Kansas City’s Booker McDaniel, and scored one of the East’s five runs that inning, but that was not enough in a 9-6 loss.65 Byrd’s turn as a pinch-hitter was no fluke. Holway recounted, “Like many other black pitchers, Bill was a threat at bat as well. He pitched righthanded but batted left or right. The left side was his strong side. … Byrd played in the outfield between starts.”66

The 1946 games marked Byrd’s last selections to the East-West Classic (despite another lackluster regular season in which he finished 4-7 with a 4.48 ERA). In Washington on August 15, Byrd threw the middle three innings. He entered the game to stop a West rally, and the East mounted a comeback to win, 6-3, with Byrd as the winning pitcher. In his worst stint in All-Star play, Byrd pitched 1⅓ innings at Comiskey Park three days later and gave up all four runs the West scored in its 4-1 triumph.67

Byrd’s All-Star legacy had him tied for second with most games pitched (7); tied for the most wins with two along with Dan Bankhead and Satchel Paige; third with most innings pitched (16 over seven games), and fifth-most strikeouts at 10.68

The collapse of the Negro Leagues on the heels of the gradual integration of the National and American Leagues and their minor leagues foreclosed any further baseball pursuits for Byrd (now in his 40s) save for the occasional semipro game. He found work in Philadelphia at General Electric as a stockman and retired in his 60.69 After a prolonged bout with cancer, Byrd died at the age of 83 at the Medical College of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.70

The Baltimore Sun’s Bill Glauber captured the essence of Bill Byrd, his career, and legacy, writing, “Bill Byrd was a pitcher who threw spitballs and a pioneer who helped pave the way for the integration of baseball. Others were more charismatic, and brought greater talent to the game, but Byrd was a seemingly indestructible master who became the symbol of the Baltimore Elite Giants during a Negro League career that spanned two decades.” One of the winningest pitchers in Negro League history, “he also will be remembered as a teacher of future major-leaguers Roy Campanella, Jim Gilliam, and Joe Black.”71 So important was Byrd held in the esteem of younger ballplayers that he was known as “Daddy.”72

Byrd finished his career with a 108-69 record (.610) with a 3.34 ERA in Negro League play. According to one statistical analysis, Byrd is the best pitcher of the Negro League’s final decade not currently enshrined in Cooperstown:

Byrd’s lifetime winning percentage was in excess of .600 from 1932 to 1950, during which he had only one losing season. His career WAR of 33.4 through 1948 is higher than that of four other Negro League Hall of Fame pitchers, including contemporaries Leon Day and Hilton Smith. … According to Seamheads, he accumulated the ninth highest number of wins of any pitcher in official American Negro League games, even though Byrd often pitched for lesser teams. As his teammate Roy Campanella put it when arguing for Byrd’s admission to the Hall of Fame, “He was a good pitcher, and he was good for a long time.”73

Byrd’s 12-3 1949 season which, while not official yet,74 further augments his career numbers. Holway’s examination of Byrd led him to consider Byrd “Cy Young”-worthy in 1942, 1948, and 1949 (Holway’s George Stovey award). Byrd was a finalist in the 2006 voting for the Negro League class inducted that year.75 Others may deservedly have been chosen for the Hall before him, but greater awareness of his career as the Elite Giants’ rotation anchor speaks to his ultimate merit. Asked about his career and whether he was bitter over not having a chance to play in the White major leagues, Byrd said, “No. Well, I did the best I could.”76

Sources

Except where otherwise noted, all cited statistics are from Seamheads.com.

Notes

1 Bill Glauber, “Bill Byrd, Negro Leaguer, Dies at 83/Baltimore Pitcher Trained Big Leaguers,” Baltimore Sun, January 7, 1991.

2 Baseball Hall of Fame player profile, received January 1973, included in the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s player file.

3 “Byrd to Play Here Friday,” Columbus Dispatch, May 31, 1945.

4 John Holway, “The Original Baltimore Byrd,” Baseball Research Journal 19 (1990): 24.

5 Dr. Layton Revel, “Forgotten Heroes: Bill Byrd,” http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Hero/422255%20Center%20for%20Negro%20League%20Baseball_Bill%20Byrd.pdf, accessed July 6, 2023.

6 William J. Plott, The Negro Southern League: A Baseball History, 1920-1951 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2015), 98.

7 Revel, 4.

8 Andrea Williams, “Tom Wilson, Black Baseball and Nashville’s Connection to the Negro Leagues,” nashvillescene.com, 3. Last accessed on May 29, 2023.

9 Thomas E. Pfundstein, “Black Baseball in Cleveland, 1920–1950,” Unpublished MA thesis, John Carroll University, 1996. Special thanks to the Cuyahoga County Public Library for their help in confirming this source.

10 See these websites that provide the estimated African American population in Nashville and Cleveland, respectively: Black Bottom | Tennessee Encyclopedia and AFRICAN AMERICANS | Encyclopedia of Cleveland History | Case Western Reserve University.

11 California Eagle, March 29, 1935: 7. The article states that “The Negro Baseball association has its plans all set now for the season. The roster will be the Philadelphia Stars, Chicago American Giants, Newark Dodgers, New York Cubans, Brooklyn Eagles, Pittsburg Crawfords, and the Detroit Elite Giants.”

12 Perhaps a derivative name from the Columbus Red Birds of the American Association, which was similarly organized in 1931.

13 “Black Baseball in Cleveland,” 13.

14 Holway, 24. This same accolade is due Davis for his tutoring of Chet Brewer, who also threw a spitter.

15 Holway, 24.

16 “Black Baseball in Cleveland,” 16.

17 Revel, 6.

18 Candy Jim Taylor, “Mackey to Catch for Crack D.C. Ball Club,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 18, 1936: 15.

19 “May Transfer Elite Giants from Washington to Balto,” Baltimore Afro-American, February 5, 1938.

20 Bob Luke, The Baltimore Elite Giants (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 16.

21 Luke, 18-19.

22 Luke, 23.

23 Luke, 42.

24 Luke 43-51. Also “Homestead Grays, Elites Divide Pair,” Chicago Defender, September 23, 1939: 8.

25 As quoted in Luke, 51-52.

26 William F. McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season: Pay for Play Outside the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2007), 117.

27 McNeil, 117.

28 McNeil, 117.

29 McNeil, 121.

30 Winter League rules capped international players at no more than three for each team.

31 Thomas E. Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers: Sixty Seasons of Puerto Rican Winter League Ball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1999), 214.

32 Van Hyning, 201.

33 McNeil, 120.

34 Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 90.

35 Lanctot, 91.

36 Wendell Smith, “Smitty’s Sports Spurts,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 5, 1941: 17.

37 Chester Washington, “Sez Ches,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 18, 1940: 16.

38 Holway, 26.

39 Revel, 21.

40 Leslie A. Heaphy, The Negro Leagues, 1869-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2003), 168.

41 Lanctot, 90.

42 Heaphy, 169.

43 Holway, 23.

44 Holway, 24.

45 Luke, 37-38.

46 Holway, 24.

47 The Elite Giants also lost Wild Bill Wright and Tom Glover to Mexico; see Luke, 59.

48 Van Hyning 13-14.

49 Buster Miller, “The Sports Parade,” New York Age, March 22, 1941: 11.

50 Luke, 63.

51 McNeil, 123.

52 “Elites Shade Memphis Red Sox,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 26, 1941: 19. See also Revel, 21.

53 “12,000 Witness Stadium Classic,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 11, 1942: 16.

54 James A. Riley, Dandy, Day, and the Devil (Cocoa, Florida: TK Publishers, 1987), 112.

55 Holway, 26.

56 McNeil, 105.

57 Revel, 31.

58 Byrd was Baltimore’s Opening Day starter that year, pitching a complete-game victory in a 20-4 defeat of the Philadelphia Stars on May 3 in Philadelphia. Luke, 105.

59 Baltimore’s papers covered the series in detail. “Elite Giants Bow, 6-0, to Homestead Grays,” Baltimore Sun, September 15, 1948: 23. “Homestead Nine Beats Elites Again in Playoff,” Baltimore Sun, September 17, 1948: 17. “Grays and Elites Play 4-4 Tie in Series Game,” Baltimore Sun, September 18, 1948: 11. “Elites Test Homestead,” Baltimore Evening Sun, September 18, 1948: 9. “Elites Top Homestead in Playoff Test, 11-3,” Baltimore Sun, September 20, 1948: 13. “League Upholds Grays Protest,” Baltimore Sun, September 21, 1948: 20. “Elites Lose by Forfeit,” Baltimore Evening Sun, September 21, 1948: 27.

60 “Official 1949 NAL Pitching Records,” Center for Negro League Baseball Research, http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Stats/NAL%201949/NAL1949.pdf, accessed July 11, 2023.

61 “Elites Take NAL Title in Four Straight,” Chicago Defender, October 1, 1949: 15.

62 Luke, 128.

63 “Stars Defeat Clowns 13-0,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 6, 1944: 40.

64 “Satch Paige, Josh Gibson at Stadium on August 18,” Cleveland Call Post, August 15, 1942.

65Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 230.

66 Holway, 24.

67 Lester, 82, 125, 130, 155, 186, 216, 230, 249, 255.

68 Lester, 479-480.

69 Holway, 27.

70 “William (Bill) Byrd; Pitcher, 83,” New York Times, January 9, 1991: D21.

71 Bill Glauber, “Bill Byrd, Negro Leaguer, Dies at 83 Baltimore Pitcher Trained Big Leaguers,” Baltimore Sun, January 7, 1991.

72 Roy Campanella, It’s Good to Be Alive (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 66.

73 Steven R. Greenes, Negro Leaguers in the Hall of Fame: The Case for Inducting 24 Overlooked Ballplayers (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2020), 146-47.

74 Official Negro League statistics as of 2023 reflected only certain leagues/seasons from 1920 to 1948 as being “major league.”

75 Greenes, 149.

76 Holway, 27.

Full Name

William Byrd

Born

July 15, 1907 at Canton, GA (USA)

Died

January 4, 1991 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.