Dan Ford

Disco music peaked in the United States with the top six songs on the Billboard Hot 100 chart during the week ending July 21, 1979. At the time, “Disco Dan” Ford was starring for the California Angels club that was headed for that franchise’s first postseason appearance.1 Although the musical genre quickly fell out of fashion, Ford’s career didn’t, as he spent 11 seasons (1975-1985) in the majors with the Twins, Angels and Orioles before chronic knee problems ended his career. The right-handed hitting outfielder played for Baltimore’s 1983 World Series champions.

Disco music peaked in the United States with the top six songs on the Billboard Hot 100 chart during the week ending July 21, 1979. At the time, “Disco Dan” Ford was starring for the California Angels club that was headed for that franchise’s first postseason appearance.1 Although the musical genre quickly fell out of fashion, Ford’s career didn’t, as he spent 11 seasons (1975-1985) in the majors with the Twins, Angels and Orioles before chronic knee problems ended his career. The right-handed hitting outfielder played for Baltimore’s 1983 World Series champions.

On May 19, 1952, Darnell Glenn “Dan” Ford was born in Los Angeles. His father, Robert Ford – a farmer’s son from Bossier, Louisiana – had married Callie Mae Hunt in 1942 and entered the army shortly thereafter. By 1950, the couple had settled in L.A. and welcomed Dan’s older brother, Robert Jr. The census recorded that the elder Robert painted windows and doors for a paint company.

The Brooklyn Dodgers moved to Los Angeles shortly before Dan turned six. “As a kid I was a Dodgers fan and liked Maury] Wills and thought Jim Fregosi [who debuted with the expansion 1961 Angels) was a very good player, too,” Ford said. “In coming up I had good support from my parents. My dad played a little semipro ball.”2 Ford played three years of Little League baseball in South Park before advancing to Connie Mack competition.3 “I started out in kid baseball as a pitcher but one day my arm got sore, so I stopped that,” he said. “My two heroes have been Willie Mays and Hank Aaron.”4

Ford grew up in the Watts neighborhood, where six days of rioting over allegations of police brutality during the summer of 1965 left 34 dead. “Being athletic kept me away from a lot of things that could have affected my life,” he said.5 Based on his address, Ford began attending Jefferson High School the following year, but he said, “Playing ball throughout the city and meeting guys, guys were talking about Fremont.” Recent Fremont graduates Bobby Tolan, Willie Crawford, and Bob Watson had already commenced lengthy major-league careers. “I said, ‘I got to go there,’” Ford recalled. “That was one of the things I think I cried about with my dad; to transfer me to go to Fremont High School.”6

Future All-Stars George Hendrick (class of ’68) and Chet Lemon (’72) were among Ford’s teammates at Fremont. In 1968, Ford was named the 10th grade’s most outstanding athlete. He hit a 430-foot homer and made the All-Southern California All-Star team for the first of three consecutive years.7 He was also a star halfback for the Pathfinders’ football squad until he strained a knee ligament.8 Ford became a defensive safety before dropping football altogether following his junior year.9

When Fremont won the Southern League baseball championship in 1969, Ford was the Pathfinders’ MVP and made the All-City team. “He thinks maturely, tries to reason with himself, and is very even-tempered,” observed Fremont coach Dave Yanal. “I’ve never had a finer athlete, not only because of his physical capability, but his attitude.”10

That summer, Ford helped his Newton Street Los Angeles Police Department club reach the Joe DiMaggio League playoffs. Twin brothers Marshall and Mike Edwards were also on the team. As a senior, Ford batted .495 for Fremont to earn All-City recognition again. The Pathfinders defended their title and reached the city semifinals. Ford concluded his high school career by going 2-for-4 in the Cal-Pal All-Star Baseball Classic at Anaheim Stadium, including a homer to right-center field. He had already signed a letter of intent to attend the University of Southern California on a baseball scholarship and been selected by the Oakland A’s in the first round (18th overall) of the 1970 June amateur draft.11 “Whatever he is paid to sign, he’ll be worth every penny of it – not only as a ball player, but as a person,” said Yanal,12

To negotiate, Ford and his father turned to Charles E. Lloyd, the prominent local attorney who had helped 1967 first-round pick Wayne Simpson come to terms with the Cincinnati Reds.13 In mid-August, Ford – underwhelmed by Oakland’s reported $17,000 offer14 – announced that he would matriculate at USC.15 But the A’s convinced him to turn professional on September 15.16 The signing scout, Phil Pote, had coached Fremont when Tolan, Watson, and Crawford played there.17 Ford received a “substantial bonus.” Since the minor-league season was already over, he reported to the Arizona Instructional League.18

Ford debuted in the Class A Midwest League in 1971 by batting .267 in 107 games for the Burlington (Iowa) Bees. He led the team with 80 RBIs, tied for the top spot with 14 homers, and went deep in the circuit’s All-Star Game.19

In November, Ford married Patricia Sneed, who had given birth to Darnell Jr. (daughter Kimberly followed in 1977). Ford spent most of his offseason serving a National Guard commitment in Bell, California, causing him to miss the beginning of the 1972 season. He had not picked up a bat or ball in months when he returned to Burlington, and he admitted that he worried about being rusty.20 He allayed those concerns by hitting .354 with a team-high 18 homers despite appearing in just 72 of the Bees’ 128 games.

In 1973, Ford attended major-league spring training with the reigning World Series champion A’s. He was assigned to the Triple-A Pacific Coast League and helped the Tucson (Arizona) Toros post the loop’s best regular season record. In 128 games, he batted .293 with 14 homers, 12 triples and 16 steals. His 16 outfield assists tied for most in the circuit. Ford’s hitting streak ended at 22 consecutive games on July 19, in part because he was robbed of a homer by fellow Fremont alum Brock Davis.21 “From my point of view, I’m ready right now for major league ball,” Ford told The Sporting News in September. “Of course, I’m not the one who’s going to make that decision.”22

Oakland’s starting outfield – Joe Rudi in left, Bill North in center, and Reggie Jackson in right – was set, and the club had won a second straight World Series in 1973. Under new A’s manager Al Dark in 1974, playing time was scarce even during spring training, prompting Ford to say, “Suppose they have to call one of us up during the season. It’s one thing to read about how we’re doing, but it’s better to see for yourself.”23

Ford’s chance to stick as a reserve disappeared when the A’s opted to keep Herb Washington, a sprinter who had never played professional baseball, on the roster as a pinch runner. “I don’t understand it,” Ford told the Oakland Tribune. “But I’d rather go somewhere where I can play every day.”24 He returned to Tucson and batted .273 with 12 homers in 115 games.

Less than week after Oakland won a third consecutive World Series title, Ford and minor-league pitcher Dennis Myers were traded to the Minnesota Twins for former A’s backup first baseman Pat Bourque.25 “I was happy to be traded to the Twins. I felt when the deal was made I would get a chance to play,” Ford said.26

Ford made the 1975 Twins’ roster as a sixth outfielder. On April 12 in Kansas City, he debuted in right field at the tail end of Minnesota’s 10-inning loss. Four days later, he started in center and went 2-for-5 at Metropolitan Stadium, with singles off Angels relievers Steve Blateric and Orlando Peña. But Ford started just 10 of the Twins’ first 47 contests. His opportunity arrived following a series of injuries to other players and the trade of veteran Bobby Darwin.27 In 24 starts in June, Ford batted .305 with his first seven major-league homers, including an inside-the-parker against Oakland’s Vida Blue. He remained Minnesota’s primary center fielder for the rest of the season.

In a Fourth of July doubleheader against the Rangers, Ford homered three times. He notched his first four-hit game on August 8 in Detroit. In 130 appearances, he batted .280 with a team-high 15 homers. “In the minors I was a dead pull hitter,” he said. “[Twins teammates Rod] Carew and also Tony Oliva helped me in my hitting… Especially with sliders.”28

In 1976, Ford shifted to right field for the Twins, while his former high school opponent, Lyman Bostock, manned center. On April 15 against Rudy May, Ford hit the first homer at Yankee Stadium since that ballpark reopened following two years of renovations. Ford finished among the AL’s top 10 in extra-base hits (51), homers (20), slugging (.457), and runs scored (87), while batting .267 in 145 games. He also stole 17 bases – his major-league best – as Minnesota rode a strong second half to an 85-77 record.

Ford started slowly in 1977, batting just .221 through June 27. But he hit .309 afterwards to finish at .267 for the second straight year. His homer total declined from 20 to 11, however, and his RBIs slipped from 86 to 60. During spring training 1978, Oliva – by then a full-time coach – suggested that Ford back away from home plate. “When I stood on top of the plate, I got jammed a lot with inside pitches,” Ford explained. “Especially early in the season before I had developed my timing.”29

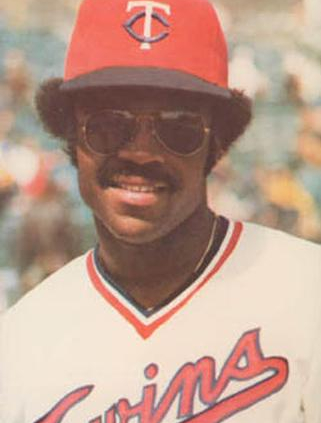

Bostock had gone to the Angels as a free agent, so Ford moved back to center field in 1978. One writer called him the “Wooshmobile” because of Ford’s ability to run a long way to make catches.30 But the nickname that stuck was “Disco Dan.” “I used to go to this club in Minnesota and got friendly with the people there. They put on disco and came out with a t-shirt of me and the nickname came out because of that,” Ford explained.31 Some games at Metropolitan Stadium featured 200 to 300 fans in “Disco Dan” Ford shirts sitting together in the outfield sections.32

Ford described his playing style as “Very fluid, as easy as possible. The game is as hard as you make it.”33 But, he noted, “it was like oil and water” when Gene Mauch became the Twins manager in 1976.34 “Nobody could break his rules. You can’t play flip, you can’t eat sunflower seeds, you can’t drink a Coke on the bench. You couldn’t play cards in the clubhouse. No checkers, no nothing. I was playing backgammon once and he told me to put the damn game up. I kept playing. He got ticked. No music. Somebody said my radio was too loud.”35

Mauch said, “I don’t think there’s any limit to how good [Ford] can be.” To progress from good to great, though – like Mays, Aaron or Roberto Clemente, for example – the manager believed that Ford had to be more committed. “In order for Dan Ford to get to that level, he has to live it. I mean live it.”36

Ford appeared in a career high 151 games in 1978 and established personal bests with 36 doubles and 11 triples, but the Twins rebuffed his efforts to secure a long-term contract. “[Twins owner Calvin] Griffith kept putting me off,” Ford said later. “I asked for $1.2 million over five years. They said, no way, I was mediocre, I played when I wanted to, crap like that.”37

On the penultimate weekend of the 1978 regular season, Bostock was murdered in Gary, Indiana. He was just 27. “When I saw Danny in the clubhouse with tears in his eyes, well, that’s something because Danny’s very cool,” Carew told a reporter. Ford acknowledged, “It’s a deep personal loss for me.”38

One week later, the Minneapolis Tribune reported offensive statements made by Griffith at the Waseca Lions Club. “I found out you only had 15,000 blacks here,” said Griffith about his decision to move his Washington Senators to Minnesota in 1961. “We came here because you’ve got good, hardworking white people here.”39 Ford responded, “If he said them, I’m pretty sure he meant them… This is going to be a burden for people to put this uniform on.”40

On December 4, 1978, Ford was traded to the Angels for corner infielder Ron Jackson and former number-one overall draft pick Danny Goodwin. “This is like a dream come true,” Ford said. “I’m home. It’s like being in high school again.”41 In February, his contract was extended through 1983.42 California also dealt four more players to Minnesota for Carew.

Jim Fregosi – by then Angels manager – predicted, “Danny [Ford] will be a better player on this club. He can drive in 100 runs and he gets a lot of extra-base hits.”43 California already had Gold Glove center fielder Rick Miller, so Ford moved back to right and remained there for the rest of his career. In the four-game series at Seattle to begin the 1979 season, Ford homered three times. But he hurt his right knee making a diving catch in California’s home opener against the Twins and missed the next 10 games.44

Ford mostly hit second in the Angels’ batting order until June 2, when he moved into the third slot, in front of cleanup man Don Baylor. “I told Donny that I’d let him lead the world while I set things up for him,” Ford recalled. “I am saying that I did my part, that I made a lot of things happen.”45 After Baylor led the majors with 139 RBIs and claimed AL MVP honors, he noted, “Danny Ford really started hitting when he went to the number-three spot. He really enjoys it.”46

Angels coach Deron Johnson convinced Ford to take more batting practice and spend less pre-game time meditating.47 “Dan just had his own way of doing things. He used to drive us crazy before games,” recalled second baseman Bobby Grich. “We would have a 1:05 game and Dan would still be in his socks, shorts and t-shirt at 1:02. At 1:04 he would buckle his pants and, at 1:05, he would walk into the dugout and say, ‘I thought you guys would never make it.’ It would break us up.”48

In August, Ford tied Fregosi’s club record with hits in eight consecutive at-bats, including a cycle performance in Oakland.49 In September, Ford drove in 22 runs in 21 games, including all four in the 4-3 victory over the three-time defending AL West champion Royals that clinched California’s first-ever division title. “Just call me Mr. Clutch,” he said. “I’m the image of [Basketball Hall of Famer] Jerry West for the Angels. He was the guy you wanted to give the ball to going down the court on the fast break.”50 Ford produced personal bests in batting (.290), RBIs (101), runs scored (100), and homers (21). Fans at Anaheim Stadium displayed a “Disco’s Noisy Fans” banner in right field, though Ford said, “My wife says she’s tired of the Disco image. She says it isn’t the real me.”51

In the ALCS, Ford homered in the first inning of each of the first two games in Baltimore (off future Hall of Famer Jim Palmer, and 1979 AL Cy Young Award winner Mike Flanagan.) The Angels lost both contests, however, and dropped the series, three games to one, despite Ford’s .294 (5-for-17) average.

In November, Ford underwent supposedly routine surgery on his right knee, but it turned into a five-hour ordeal in which bone and cartilage were removed from both sides of the joint. Although he was expected to miss the first month of the 1980 season, he started on Opening Day and went deep against Cleveland.52 Ford batted just .220 with two homers through May 28, however, and landed on the disabled list for more than two months. “I came back too soon,” he acknowledged.53

Without Ford, California sank into last place with a 29-48 record before the All-Star break. He was still limping when he returned to action on August 8 by going 3-for-4 with a homer. Angels fans gave him a standing ovation when he was replaced by a pinch-runner in the seventh inning.54 He appeared in 33 of California’s last 54 contests and batted .343, including a career-best 16-game hitting streak.55

Ford’s 1981 season was full of controversy. After Ford homered off right-hander Mike Norris in Oakland on April 29, A’s catcher Mike Heath tried to inspect his bat, setting off a tug-of-war in which both benches cleared. Umpire Jerry Neudecker used a pocketknife to cut off the end of Ford’s lumber but found nothing illegal. When the top of Ford’s bat broke off on September 4 in Cleveland, however, umpire Dallas Parks spied cork. Ford was suspended for three games and fined $500. “I just got caught,” Ford said. “I was going bad, and the team was going bad. I was trying to do something to help the team… I had that bat a long time, but I didn’t use it until [that road trip].”56

In between those two incidents, Ford appeared naked in the July issue of Playgirl, prompting Angels GM Buzzie Bavasi to threaten to sue the magazine for using the Angels’ logo without permission.57 Meanwhile, California fired Fregosi in late May and replaced him with Mauch, who had been axed by the Twins the previous summer.

Ford’s .767 OPS ranked second on the team behind Grich in ’81, and he said he resented the lack of recognition he received. “It’s probably because of the people we have. Guys like [Fred] Lynn and Carew and Don Baylor who’ve been MVPs, batting champs, All-Stars,” Ford said. “I’ve never been on an All-Star team, even when I had a super season. The only thing I’ve ever heard against me was, ‘That guy can really play if he ever makes up his mind to play.’”58

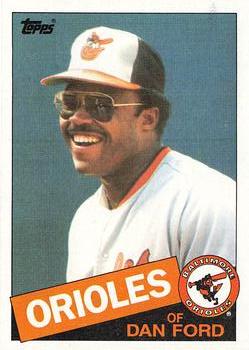

California failed to win the AL West in either half of the strike-shortened, split season, and finished 51-59. On January 28, 1982, the Angels traded Ford to the Orioles for third baseman Doug DeCinces and lefty Jeff Schneider.

“[Orioles manager] Earl Weaver told me, ‘You’ll hit behind Eddie Murray,’” Ford recalled. “That was fine by me… Eddie and I grew up together in Watts.”59 Ford collected three hits in his Baltimore debut, including a three-run homer, but he didn’t raise his batting average above .200 to stay until May 26.

The Orioles battled the Brewers for the AL East title until the final day of the regular season but – while DeCinces had a career year for the Angels – Ford lost his regular job and started only nine of the last 32 games. Overall, Ford batted .235 with 10 homers in 123 appearances while starting at six different spots in the batting order. “Everything seemed to happen so fast,” he reflected. “I tried all kinds of different things to come out of the slump and nothing worked. I started pressing and everything kind of came apart.”60

Weaver retired and Joe Altobelli became the Orioles manager for 1983. “They came to me in spring training and said they wanted me to hit second and be the right fielder,” Ford recalled. “They said, ‘Let’s try to put last year behind us.’ They took the load off my back.”61 On Opening Day in Baltimore, Ford was booed for dropping the first ball hit his way for an error.62 Through May 19, however, the Orioles had the AL’s best record and Ford was batting .350 with game-winning RBIs in three consecutive games. His homer in a 1-0 victory on May 18 broke up White Sox righty Richard Dotson’s bid for a no-hitter with one out in the bottom of the eighth. The following night in Toronto, Ford snapped another scoreless, eighth-inning tie with a two-run blast.

Weaver retired and Joe Altobelli became the Orioles manager for 1983. “They came to me in spring training and said they wanted me to hit second and be the right fielder,” Ford recalled. “They said, ‘Let’s try to put last year behind us.’ They took the load off my back.”61 On Opening Day in Baltimore, Ford was booed for dropping the first ball hit his way for an error.62 Through May 19, however, the Orioles had the AL’s best record and Ford was batting .350 with game-winning RBIs in three consecutive games. His homer in a 1-0 victory on May 18 broke up White Sox righty Richard Dotson’s bid for a no-hitter with one out in the bottom of the eighth. The following night in Toronto, Ford snapped another scoreless, eighth-inning tie with a two-run blast.

But Ford strained his left knee on the artificial turf in Minnesota on June 1. He aggravated the injury by trying to come back too soon and underwent arthroscopic surgery on June 28.63 He returned on July 20, batting leadoff in Seattle, and produced the only three-homer game of his career. On August 25, Ford’s two-run double in the bottom of the 10th beat the Blue Jays, 2-1. In 103 games, he hit 30 two-baggers and batted .280 – including .348 with runners in scoring position.

In Game One of the ALCS, Ford aggravated his sprained right foot rounding first base after a ninth-inning double.64 The Orioles beat the White Sox in four games to win the pennant, but he did not start again until Game Two of the World Series against the Phillies. In the fifth inning of that contest, Ford’s glasses were broken by a slider from Philadelphia reliever Willie Hernández that skimmed off the bill of his batting helmet. “I had never been hit in the head before… I was scared,” he admitted.65 But Ford stayed in the game and singled in his next at-bat to help the Orioles even the series. In Game Three at Veterans Stadium, his towering sixth-inning homer off future Hall of Famer Steve Carlton started Baltimore’s rally to a come-from-behind victory. Two days later, the Orioles were World Series champions.

Ford became a free agent, and nearly signed a deal to play in Japan. When the Orioles increased their offer from two guaranteed years to three, he re-signed with Baltimore in January 1984.66 Because of his uncertain status, Ford had not received offseason medical attention for his troublesome left knee. He appeared in only six games before it locked up on him on April 15, necessitating another arthroscopic surgery. “There was certainly enough evidence to suggest he should have been operated on last winter,” remarked Baltimore GM Hank Peters. “But at that point he didn’t belong to any club. It’s a set of circumstances that is part of the system. I certainly don’t fault him.”67

More than three months passed before Ford returned to action on July 20. On August 7, he fractured his right wrist in a collision with Cleveland catcher Chris Bando. He kept playing until the injury was diagnosed on August 15, then missed the remainder of the season.68 Ford appeared in just 25 games in 1984, batting .231 with one homer in 91 at-bats.

He began 1985 as a platoon DH/pinch-hitter for Baltimore. In 75 at-bats before the end of May, Ford hit .187 with one homer. The Orioles placed him on the disabled list, and he underwent a season-ending operation on his left knee in July.69

On January 23, 1986, the Orioles released Ford, despite owing him $450,000 for the remaining year on his contract. Peters cited reduced roster sizes and Ford’s inability to play defense with his bad knee. “If we go with 24 [players],” Peters explained. “It would be a luxury to carry a player who can only stand at the plate and swing a bat.”70 Ford finished his 11-year major-league career with a .270 batting average and 121 homers in 1,153 games.

Ford spent four years helping to run his family’s ranch in Louisiana before he moved back to California to scout for the A’s.71 “Didn’t like it much,” he said. “Judging talent isn’t easy.”72 Next, he teamed up with former Twins pitcher and L.A. native Darrell Jackson to form the Athletic Connection Team, which helped athletes adjust to life after sports.73 Ford also described ACT as an “intervention program” that “worked with tough kids.”74

In 2007, the Los Angeles Sentinel reported that Ford was in the real estate business and raising horses.75 “I acquired some horses a few years ago by just love of horses,” he told an interviewer in 2020. “I got into the trail riding competition which was really a lot of fun… It gave me a lot of, I guess, a sense of responsibility again, a sense of dedication… I really learned a lot based upon dealing with horses… They also had to train me just as well so I could be a better horseman.”76

Whereas Ford opted to enter professional baseball rather than attend USC on a baseball scholarship, his grandson became a wide receiver for the Trojans’ football squad. In January 2023, Kyle Ford transferred to rival UCLA for his senior year.

As of 2023, Dan Ford resided in Benton, Louisiana, and owned Paycation Travel.77

Last revised: April 11, 2023

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Dan Ford for his helpful input.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and David Bilmes and fact-checked by Rod Nelson.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com, www.retrosheet.org and https://sabr.org/bioproject.

Notes

1 First through sixth, the songs were: “Bad Girls” by Donna Summer, “Ring My Bell” by Anita Ward, “Hot Stuff” by Donna Summer, “Good Times” by Chic, “Makin’ It” by David Naughton, and “Boogie Wonderland” by Earth, Wind & Fire, featuring The Emotions. Troy Brownfield, “The Week of Peak Disco,” Saturday Evening Post, July 22, 2019, https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2019/07/the-week-of-peak-disco/ (last accessed February 11, 2023).

2 “‘Disco’ Dan Ford: the One More Inning Interview,” BaseballGuru, June 2003, http://baseballguru.com/omi/DISCODAN.htm (last accessed August 21, 2022).

3 Dan Ford, Publicity Questionnaire for William J. Weiss, November 18, 1970.

4 Regis McAuley, “Fast-Moving Ford Makes Easy Adjustment as Toro,” The Sporting News, September 15, 1973: 23.

5 “‘Disco’ Dan Ford: the One More Inning Interview.”

6 Anthony LaPanta, “Checking in with Dan Ford,” Minnesota Twins YouTube channel, September 23, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WJd5350PqpM (last accessed August 21, 2022).

7 Ford, Publicity Questionnaire for William J. Weiss.

8 Mark Heisler, “Angel Notes,” Los Angeles Times, April 14, 1979: D1.

9 Brad Pye Jr., “RC Cola Prep of the Month,” Los Angeles Sentinel, July 2, 1970: B3.

10 Pye Jr., “RC Cola Prep of the Month.”

11 “Fremont’s Ford Signs With USC,” Los Angeles Times, May 26, 1970: D3.

12 Pye Jr., “RC Cola Prep of the Month.”

13 Brad Pye, Jr., “A Swinging Brock,” Los Angeles Sentinel, July 9, 1970: B1.

14 Loel Schrader, “Haden Showcased Against Millikan,” Independent (Long Beach, California), September 21, 1970: 19.

15 “Ford Rejects A’s,” Los Angeles Sentinel, August 13, 1970: B1.

16 Brad Pye, Jr., “Prying Pye,” Los Angeles Sentinel, September 17, 1970: B4.

17 Ford, Publicity Questionnaire for William J. Weiss.

18 “Fremont Star Ford Signs with Oakland,” Los Angeles Times, September 19, 1970: D6.

19 “Stars Shine Bright,” The Sporting News, July 31, 1971: 44.

20 McAuley, “Fast-Moving Ford Makes Easy Adjustment as Toro.”

21 “Spillner Stops Ford,” The Sporting News, August 4, 1973: 38.

22 McAuley, “Fast-Moving Ford Makes Easy Adjustment as Toro.”

23 Ron Bergman, “A Ford to Run on A’s Farm,” Oakland Tribune, March 20, 1974: 37.

24 Bergman, “A Ford to Run on A’s Farm.”

25 Oakland released Bourque in spring training 1975 after he refused an assignment to Triple A. Bourque finished his career in the Mexican League, where he played until 1979. Clayton Trutor, “Pat Bourque,” https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/pat-bourque/ (last accessed August 23, 2022).

26 Bob Fowler, “Twins Find a Ford in Their Present,” The Sporting News, July 12, 1975: 17.

27 Fowler, “Twins Find a Ford in Their Present.”

28 “‘Disco’ Dan Ford: the One More Inning Interview.”

29 Fowler, “Twins Find a Ford in Their Present.”

30 Fowler, “Twins Find a Ford in Their Present.”

31 “‘Disco’ Dan Ford: the One More Inning Interview.”

32 Bruce Markusen, “Dan Ford and the Disco Revolution,” Hardball Times, November 9, 2018, https://tht.fangraphs.com/card-corner-plus-dan-ford-and-the-disco-revolution/ (last accessed March 14, 2022).

33 Mark Heisler, “Twin Becomes Angel,” Los Angeles Times, March 27, 1979: D1.

34 “‘Disco’ Dan Ford: the One More Inning Interview.”

35 Heisler, “Twin Becomes Angel.”

36 Heisler, “Twin Becomes Angel.”

37 Heisler, “Twin Becomes Angel.”

38 “Bostock’s Friends Die a Little,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), September 25, 1978: 30.

39 Associated Press, “The Speech Heard ‘Round Waseca,” Los Angeles Times, October 1, 1978: C2.

40 “Owner’s Remarks Infuriate Twins,” Hartford (Connecticut) Courant, October 2, 1978: 65.

41 Mike Littwin, “Angels Make the First Move,” Los Angeles Times, December 5, 1978: D1.

42 “The Newswire,” Los Angeles Times, February 17, 1979: C4.

43 Pete Donovan, “Hype is Name of the Game,” Los Angeles Times, January 5, 1979: B17.

44 Dick Miller, “Angel Notes,” The Sporting News, May 5, 1979: 29.

45 Ross Newhan, “Angels’ Ford is Right on Time for the Opener,” Los Angeles Times, April 11, 1980: E1.

46 Dick Miller, “Big-Gun Baylor Shooting for a Huge Salary Hike,” The Sporting News, December 22, 1979: 52.

47 Dick Miller, “Ford is Strictly Cadillac in Angels’ Glossary,” The Sporting News, September 8, 1979: 54.

48 Chris Foster, “‘Disco’ is Part of Sunday Afternoon Fever,” Los Angeles Times, July 15, 1991: C10.

49 Baltimore Orioles ’82 Information Guide: 100.

50 Dick Miller, “Angels Notes,” The Sporting News, September 29, 1979: 4.

51 Miller, “Ford is Strictly Cadillac in Angels’ Glossary.”

52 Ross Newhan, “Angels’ Ford is Right on Time for the Opener,” Los Angeles Times, April 11, 1980: E1.

53 Dick Miller, “There’s Doubt About a Ford in Angels’ Future,” The Sporting News, August 30, 1980: 38.

54 Miller, “There’s Doubt About a Ford in Angels’ Future.”

55 Baltimore Orioles ’82 Information Guide: 102.

56 John Strege, “Ford’s Bat Ploy Isn’t a Better Idea,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1981: 39.

57 Peter Gammons, “It’s Show Biz: Awards Must Go On,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1981: 16.

58 John Strege, “Ford’s Idea: Better Press for Batting Feats,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1981: 22.

59 “‘Disco’ Dan Ford: the One More Inning Interview.”

60 “Disco Dan Boogies to a New Beat,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1983: 12.

61 Kent Baker, “3-Year Pact Sold Ford on O’s,” Baltimore Sun, March 1, 1984: C3.

62 Jim Henneman, “Bird Seed,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1983: 24.

63 Orioles 1984 Media Guide: 128.

64 Orioles 1984 Media Guide: 128.

65 Dave Nightingale, “Rookie Boddicker Keeps on Truckin’,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1983: 15.

66 Kent Baker, “3-Year Pact Sold Ford on O’s,” Baltimore Sun, March 1, 1984: C3.

67 Jim Henneman, “Injuries Feed Birds’ Slow Start,” The Sporting News, April 30, 1984: 18.

68 Orioles Media Guide ’85: 129.

69 Richard Justice, “Briefly,” Baltimore Sun, July 19, 1985: 3E.

70 Kent Baker, “Orioles Feel Ford Has Run Out of Gas, Release Him,” Baltimore Sun, January 24, 1986: 7D.

71 Chris Foster, “‘Disco’ is Part of Sunday Afternoon Fever,” Los Angeles Times, July 15, 1991: C10.

72 “‘Disco’ Dan Ford: the One More Inning Interview.”

73 Mark Ambrogi, “ACT Helps Athletes Deal With ‘After-Life’,” Indianapolis Star, July 10, 1994: C2.

74 “‘Disco’ Dan Ford: the One More Inning Interview.”

75 Kenneth Miller, “Southern League Trailblazers Honored,” Los Angeles Sentinel, November 1, 2007: B2.

76 LaPanta, “Checking in with Dan Ford.”

77 “Dan Ford,” https://www.linkedin.com/in/dan-ford-72375777/ (last accessed August 28, 2022).

Full Name

Darnell Glenn Ford

Born

May 19, 1952 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.