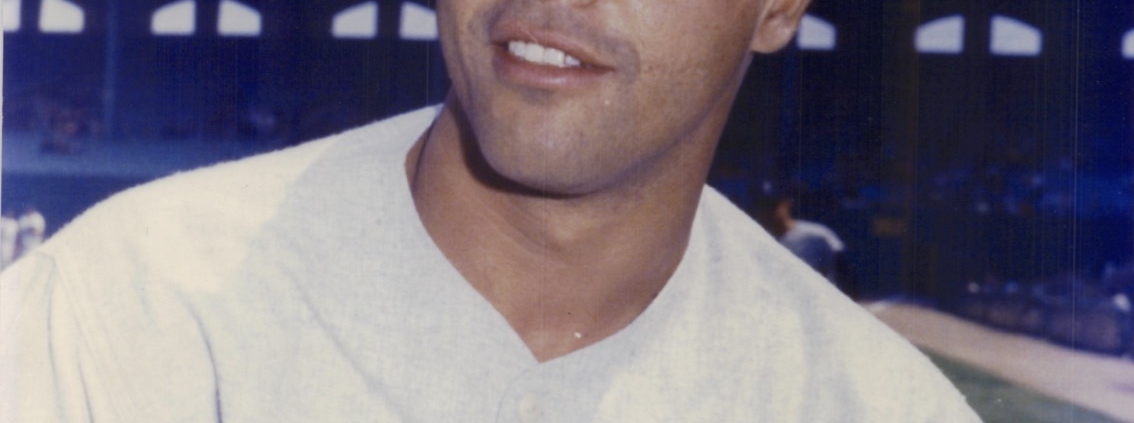

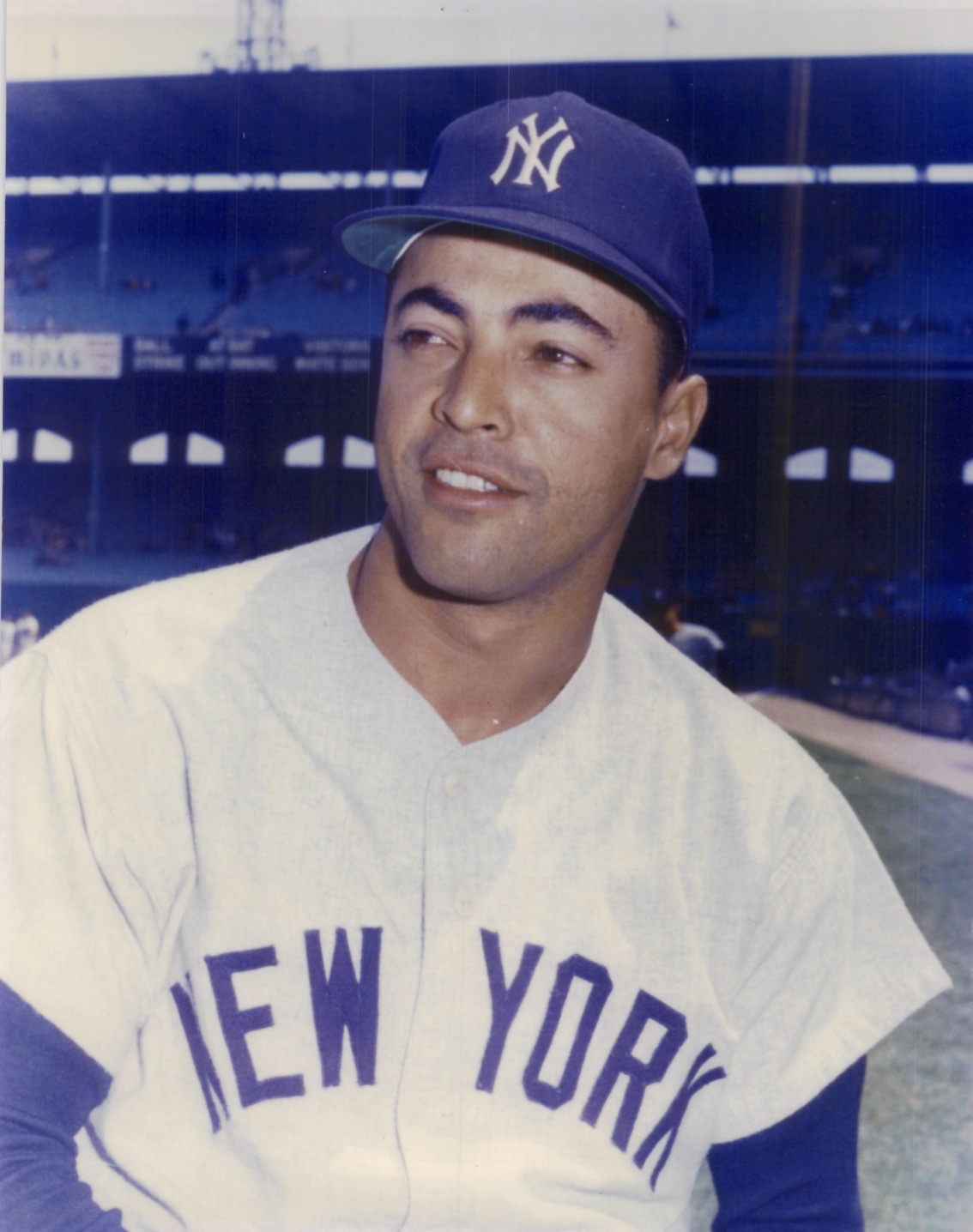

Art López

Arturo (Art) López had 49 at-bats with seven hits for the 1965 New York Yankees. He was the first player born in Puerto Rico to be originally signed by the Yankees and play for them.1 The outfielder was also the first boricua to play for a Japanese professional baseball team.

Arturo (Art) López had 49 at-bats with seven hits for the 1965 New York Yankees. He was the first player born in Puerto Rico to be originally signed by the Yankees and play for them.1 The outfielder was also the first boricua to play for a Japanese professional baseball team.

During a professional career that spanned 1961 to 1973, López was part of title-winning teams from five countries/territories— the U.S. (in the minors), Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and Japan. His international experience also included a winter-ball tournament win in Venezuela.

López was signed by the Yankees at age 24, in 1961, after four years in the U.S. Navy and two years of amateur baseball in New York City’s Central Park. He wasn’t big (5-feet-9 and 170 pounds) but had speed and a quick bat. However, a weak throwing arm (the result of injuries) short-circuited his Stateside playing career. It was not an impediment in Japan, though, where he played six solid seasons.2

López also had a strong work ethic, which propelled him not only to high-level pro ball but also to a successful business career in insurance and banking, as well as being an educator and lifelong proponent of learning.

Arturo López Rodríguez was born in Mayagüez, on May 8, 1937.3 He was the oldest child of Cristóbal López González and Aurea Rodríguez de López. Both parents’ surnames are used in Hispanic culture.

López’s father was from Las Marías, north of Mayagüez; his mother was from Cabo Rojo, south of Mayagüez.4 Luis Fernando (Tato) was the family’s second child. Two sisters, Zoraida and Zaida, followed. The youngest was named José René.

López’s parents moved to the mainland after World War II and worked in New York City’s Garment District. “Dad first moved to New York City in 1947,” recalled López. “He was an independent contractor with sewing expertise. The owner gave dad better opportunities as a mechanic. Mom (a sewing machine operator), Zaida, and my kid brother moved to New York in 1948.”5 Sad to relate, José René died on November 10, 1949. He was hit by a milk truck while trying to pick up a dropped toy. Brother Luis Fernando had previously passed away in Mayagüez.

Meanwhile, Arturo and Zoraida remained in Mayagüez for the 1948-49 school year. Their grandmother took care of them, with financial help from two uncles.

As a youth, López swam in the Caribbean Sea, climbed coconut and mango trees, and hitched rides on car fenders. He became proficient in volleyball under the tutelage of Luis Enrique “Tite” Figueroa, at the Community Center on Saturday mornings. Puerto Rico was a baseball hotbed, however, and young Art played third base in sandlot games. He also closely followed Puerto Rico’s Winter League (PRWL) and his beloved Mayagüez Indios. He transcribed PRWL games in a notebook.

From October 1946 through January 1949, López attended Mayagüez home games at Liga Paris behind the left-field fence, watching and hoping to fetch a home run ball. In 1946, his dad introduced him to Juan “Tetelo” Vargas (known as El Gamo Dominicano, the Dominican Deer), with Caguas-Guayama. López was impressed with Santurce’s Willard Brown, who was “our Babe Ruth. Brown, also a star with the Kansas City Monarchs, was the fourth person of color to play in the big leagues, playing briefly with the 1947 St. Louis Browns. Even the great Willie Mays did not reach the same plateau or heights with [Puerto Rico’s] fans as Mr. Brown.”6 Bob Thurman, Brown’s Santurce teammate, played the outfield and pitched.

López admired Ponce third baseman Howard Easterling and idolized Stateside Negro Leaguers who reinforced Mayagüez— namely, this 1948-49 quintet: Johnny Davis, Luke Easter, Wilmer Fields, Alonzo Perry. and player-manager Artie Wilson.7 Per López: “These players were instrumental in my career as a major-league player. I once played hooky from school for at least two weeks to await the team’s 10 a.m. practices and sit in the stands [alone]; follow them upon completion to a local restaurant which they frequented to have breakfast (or lunch) while I stood outside gawking at them and dreaming that someday, I, too, would become a player for the Indios de Mayagüez.”8

López was impressed by their versatility in playing different positions; he later understood the economics and relevance of this. However, his Mayagüez school notified his parents of repeated absences, which led to “a relationship with my dad’s belt and my behind.”9

In July 1949, López joined his family living in the South Bronx. He lived there through June 1954, attending Clark Junior High, PS 37, near Willis Avenue. He went on to Morris High School, attended by future Army general and U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell. The South Bronx was a melting pot of Irish, German, Jewish, and Italian residents.

López, a diehard New York Yankees fan by August 1949, enjoyed their five straight AL pennants and World Series titles. He secured free tickets to Yankees games via Sergeant Bill Simpson, 40th Precinct, 138th Street and Alexander Avenue. “I got Vic Raschi and Phil Rizzuto autographs,” recalled López, whose cousin, Carlos Galarza, later became a police officer at the same precinct.

At Morris High, López participated in track & field, including the 440-yard relay.10 He played one year of high school baseball. He tried to join the high school choir, but the musical director booted him back to the baseball team. López also took part in non-school softball leagues – as well as stickball games, which he loved. He witnessed Italian mothers yelling at their kids from the windows of high-rise apartments at 6 p.m. to come home and have dinner. López was annoyed and wanted to continue playing.11

Unlike schoolmate Colin Powell, who went on to college, López joined the U.S. Navy at 17, in 1954, without getting his high school diploma. “I was restless, when our softball team shortstop turned around one Saturday morning during a game to ask me if I wanted to join the Navy with him next week,” noted López. “We joined as planned; I never saw him again—ever.”12 López was in the USS Albany (CA123), part of the 6th Fleet. One of his captains was Admiral John McCain, father of future U.S. Senator John McCain. López earned his GED in the Navy and spent free time in the library. LaSalle Extension University offered distance learning courses, the foundation for his lifelong learning. He captained his ship’s volleyball team, including a match versus a collegiate team in Athens, Greece, and played baseball on the deck. Two of his four Navy years were spent in Norfolk, Virginia. He did gunnery and electronics work.

On December 29, 1954, 17-year old López married Mary Farley. They had five children: Laura Lee (born in 1955), Donna Marie (1958), Arturo René (1959). Lisa (1963); and Christopher James (1970).13 The first four were born in New York City; Christopher’s birthplace was Tokyo.

López (along with Mary, Laura, and Donna) lived in the South Bronx in 1958. He became a debit agent for Unity Insurance Company after getting his New York state license. He did not have a driver’s license, but made most of his collections by running or walking quickly between East Harlem high rises and dashing up steps to collect premiums after customers received their Social Security and welfare checks. López later helped persons employed by Unity Insurance get their license and better jobs.14

From 1959 to 1961, he played for Brooklyn amateur baseball teams called Friendly Tavern and Añasco. El Diario, a Spanish-language New York City newspaper, announced game times and locations. John Candelaria Sr.—father of the team’s batboy, John Candelaria—coached Friendly Tavern in 1959. Candelaria Sr. had López put on the All-Star list for games versus a visiting team from Puerto Rico. López was Co-MVP.15 Central Park League games were from May through August, but the 1959 All-Star Games took place in Brooklyn.

In 1961, the left-handed throwing and batting Lopez drew the attention of Art Dede, a veteran scout who had been working with the Yankees since 1958. In a 15-inning game at Yankee Stadium (part of a 1961 summer prospect tryout), Dede saw López fan three times versus lefties and hit three triples against right-handers.

“Over 100 kids went to that tryout,” recalled López. Dede returned for a 7 a.m. game the following Sunday at the 103rd Street field in Central Park. “I hit two grounders; struck out—threw the bat into the fence behind home plate—and hit a home run,” said López. “Dede said, ‘When you strike out, don’t throw the bat.’”16 Three days later, Dede brought a Yankees contract to López’s home. The next Sunday, López took the subway to Central Park to say good-bye to his team. He went five-for-five.

López produced in 1961 for the Harlan Smokies (Appalachian League) and Auburn Yankees (New York-Penn League). Auburn skipper Loren Babe was “dedicated, direct and feisty.”17 For the two teams combined, he posted a .345/.438/.629 slash line (1.067 OPS). Without telling Babe, López played through an ankle injury with Auburn—for “economic reasons, not logic.”18

That preceded winter ball with the 1961-62 Arecibo Wolves, a PRWL expansion team. López, unproven in the eyes of Arecibo’s manager, Luis Olmo, faced San Juan’s Luis Arroyo, aka “Tite,” who was coming off his finest season in the majors with the world champion Yankees. With the bases loaded, López hit a double over Roberto Clemente in center field in Arecibo. López felt he “had a future in baseball” after this double, with key implications for his career. 19

Before that at-bat, as López recalled, “My manager (Olmo) made signs for a pinch-hitter, 18-year old rookie Sandy Alomar Sr. [Olmo, as a scout, had signed Alomar for the Milwaukee Braves in 1960].20 I walked over to Olmo, [who was also serving as] the third-base coach, and said, ‘What the hell are you doing? I’ve faced better pitchers in the minors.’ Olmo replied: ‘If that is true, go hit.’”

As a Navy veteran competing for playing time with others (including Alomar), López felt he had something to prove. After the game, López found out that Arroyo was pissed when the veteran heard the comment that a Class D rookie had faced better pitchers. A high-caliber lefty was supposed to retire a D-ball player and lefty hitter. “That’s how I became a regular in Arecibo. We (Arroyo and myself) became good friends.’”21

To end the regular winter season, Arecibo bested San Juan in a tie-breaker game for fourth place at Sixto Escobar Stadium. López compared this to David versus Goliath, similar to when he—with just 194 Class D minor-league at-bats—doubled off Arroyo.22

In 1962, Lopez joined Class D Fort Lauderdale in the Florida State League. His 37 steals that season were one more than Cleo James of the St. Petersburg Saints. “I never ran the 100-meter dash,” claimed López, “but the Yankees wrote in one of their 1961 news handouts that I had been clocked very close to some established track record.”23 Bob Bauer, Fort Lauderdale’s skipper, was a “Ralph Houk wannabe with a cigar in his mouth, whenever the brass was in town—a real gentleman who would not drink from a bottle.”24 López’s roommate was Mike Hegan. That club was the first champion of which he was a member.

López returned to Arecibo for 1962-63, with a .278 average. Arecibo finished fourth, losing to first-place Mayagüez in the semis. López loved Arecibo; his maternal grandfather owned the city’s first semipro baseball team.25

Moving up to Class A Greensboro for 1963, López sparkled, hitting .338—but Don Bosch won the batting title despite a lower mark of .332. A severely sprained ankle cost López needed plate appearances. “I came back, got some hits and Frank Verdi benched me against lefty pitchers until I successfully convinced him otherwise. He approached me a week later aghast—I lacked at-bats to qualify for the batting title…que será, será.”26 Greensboro (85-59) won the West Division and bested the Durham Bulls in the semifinals, but lost the finals to the Wilson Tobs. “Roy White, our second baseman, was a kid brother to me,” said López. “Greensboro had great fans; one owned a bar-restaurant—cooked great steaks. Verdi was a player’s manager; sorry he was never given the opportunity to manage at the major league level.”27

The 1963-64 PRWL season was marked by an event that everybody who was old enough to remember can recall vividly; the assassination of John F. Kennedy. On November 22, 1963, López had left an Arecibo jewelry store, when teammate Jack Hamilton told him, “They just shot the President.”28

Moving on from the JFK tragedy, López posted a .337 average for Arecibo that season, fourth-best in the PRWL behind teammate Tony Oliva (.365), Ponce’s Walt Bond (.349), and San Juan’s Clemente (.345). That winter, a Puerto Rican star of the past—Francisco “Pancho” Coimbre, by then a Ponce coach and Pittsburgh Pirates scout—complimented him. Coimbre said, “Tu me acuerdas de mí con más poder.” (You remind me of myself with more power.) López “felt like a million bucks.”29

Before a late-season game, López was approached by Colonel Jennie of the Nicaraguan Armed Forces. The colonel had been tipped to López’s play by Wilfredo Calviño, skipper of a club in the Nicaraguan Winter League, Cinco Estrellas (known for its longstanding ties to the nation’s military). Calviño, in turn, knew and trusted Tony Castaño, Arecibo’s 1963-64 manager.

With fifth-place Arecibo out of the playoff hunt, López accepted Jennie’s offer. He flew first to Miami, Florida, and then to Managua, on a private jet, with just Jennie, a flight attendant, the pilot and co-pilot. His first at-bat, as a pinch-hitter, came against Ferguson Jenkins, pitching for León.

Cinco Estrellas won the February 1964 Inter-American Series, in Managua, defeating San Juan twice.30 In the title match, an Orlando Cepeda three-run homer off Willie Hooker gave San Juan a 3-0 lead, but López scored the winning run in the seventh after he tripled and scored on a sacrifice fly by Leo Posada—distant kin to future Yankees catcher Jorge Posada. Cinco Estrellas played superbly, turning frequent double plays and avoiding miscues. López felt vindicated: “A cousin alerted me I was not selected to the PRWL 1963-64 All-Star Team. That motivated me to play well.”31

López moved up again in 1964, this time bypassing Double-A and going right to Triple-A Richmond. Preston Gómez managed the 1964 Richmond Vees, after managing the 1963-64 Santurce Cangrejeros in Puerto Rico. He appreciated López, who called Gómez my “Padre Pio” (a reference to the Italian holy man, later a saint).32 In his own words, López was “stressed out realizing the possibility of playing for the Yankees, with a throwing arm acutely sore, painful and swollen, and definitely not of major-league caliber.” But Gómez gave him “tremendous confidence.”33

On April 12, 1964, Richmond hosted and defeated the Yankees, 3-2, when Horace Clarke drove in Ike Futch with an eighth-inning hit. Hitting third, López went two-for-three with two RBIs.34 The winning pitcher was Mel Stottlemyre, who was on López’s first minor-league teams in 1961.35

Another highlight of that summer was playing against childhood hero Luke Easter when Richmond faced Rochester. Easter—then age 48 and in his last professional season—hit an opposite-field homer.

López posted a .315 average in 151 games. He appreciated Richmond teammate Jack Reed, a “real gentleman” who provided insights on playing the outfield. López was observed by St. Louis Cardinals scouts when Richmond played Jacksonville, the Cardinals Triple-A farm team. He hit well against Suns pitchers Mike Cuellar, Rubén Gómez, and others. Cardinals manager Johnny Keane was told by advance scouts in August 1964 that López was “a good hitter who they [Yankees] might bring up.”36 Yet the Yankees did not call up López. Instead, Mike Hegan was promoted and replaced the injured Tony Kubek on New York’s World Series roster.

Arecibo traded López to the Caguas Criollos before the 1964-65 PRWL season. The Caguas skipper was Luis Olmo, López’s Arecibo manager, 1961-63. José Cardenal and Alex Johnson patrolled the other outfield slots. López described Johnson as “a fiery and antisocial player—the Mike Tyson of baseball.” Yet he also noted Johnson’s tender side, which emerged when López’s son Arturo René (then just five) visited during practice. “Alex truly cared for my son,” recalled López.37

Other friendships were made or maintained that winter. Preston Gómez managed Santurce. Fergie Jenkins was a Caguas teammate against whom López had played in Nicaragua. Arecibo’s Mike Cuellar and Pancho Herrera, Caguas first baseman, once had lunch at López’s Caguas home.

López and Caguas teammate Julio Navarro reinforced Águilas Cibaeñas (AC) in the postseason of the Dominican Winter League (LIDOM). López was apprehensive, but went anyway. AC swept Licey in three semifinal games. López scored Game One’s winning run, ignoring the manager’s stop sign. AC fans came to the hotel and paid his fine.38 López went 4-for-8 in this series, with a double and a triple. Escogido was favored over AC in the finals, with Juan Marichal, Fergie Jenkins, Felipe Alou, Matty Alou, Jesús Alou, and Bert Campaneris, but AC won five straight.

AC then went to Caracas, Venezuela to take part in a four-team Inter-American Series featuring the top two Venezuelan and LIDOM clubs. AC won four of six in the round robin against Escogido, the Caracas Lions, and La Guaira Sharks. Pete Rose starred for Caracas, but López impressed Venezuela’s sportswriters with a triple, two singles and three runs scored in a Game One win over La Guaira. AC was named tourney champ over Escogido, based on a tiebreaker formula. López became series MVP.

López had a fine 1965 spring training camp in Fort Lauderdale, winning the James P. Dawson Award for best performance by a Yankees rookie.39 One day, he left four tickets for the AAU Swimming Club. Four persons waited for him after the game; one was Johnny Weissmuller, the Olympic swimmer who went on to movie stardom as Tarzan. López told him, “Had I known you were here, I would not have showered; Tarzan was one of my heroes.”40

After López made the team, Clete Boyer once summoned him to the dugout to view the lineup card—Mickey Mantle (who liked the rookie), Roger Maris, Elston Howard, and Art López.41

Roger Repoz was optioned to Toledo; Duke Carmel and Ross Moschitto also went north. Héctor López and Horace Clarke were Art’s road roommates.

López’s Yankees debut came as a pinch-runner for Mantle in the ninth inning of the season opener at Minnesota on April 12, 1965. He scored his first AL run when Joe Pepitone’s pop fly was dropped. His first AL hit came off the California Angels’ Dean Chance at Yankee Stadium on April 24. Through May 31, 1965, he had four hits in 31 at-bats. In the second game of a Memorial Day twin bill that day versus Detroit, he pinch-hit for Jim Bouton and grounded to second. Bouton wore #56—the second-highest uniform number on the team after López’s #57.

On June 2, an off-day, López received a call from Johnny Keane, who’d become Yankees manager. Elston Howard was activated, with López optioned to Toledo. “Keane called me before 7 a.m. to have breakfast,” noted López.42 Keane had a tough time managing the Yankees, whose record then stood at 19-26.

After three months with Toledo, López was called up. On September 3, he played in right versus Boston at Yankee Stadium, a 9-0 shutout by Al Downing. Two days later, López went two-for-five against Boston, with hits off Jim Lonborg and Dick Radatz. On September 8 versus Washington, he was retired by Ron Kline in his last AL at-bat. López went seven for 49 with New York, including 1-for-13 pinch-hitting.

López’s 1966 season was with Toledo, a Detroit farm team, and Syracuse, a Yankees club. Frank Carswell, Syracuse skipper, gave him the impression of being a country squire. “Nothing would bother him,” said López. “He was a fine individual.”43 López didn’t play minor-league baseball in 1967, but the Yankees retained his rights. In six minor-league seasons, he posted a .287 average (706-for-2,461) with 49 homers and 311 RBIs.44

Caguas owner Dr. Emigdio Buonomo offered López the job of managing the Criollos in 1967-68, but he declined. Nino Escalera accepted and led the Caguas to the title. López’s playing time was limited, due to a crowded outfield contingent including Cleon Jones, John Briggs,Ted Savage, Joe Christopher and Jerry Morales. He got just 50 at-bats and had seven hits. As it developed, that was López’s last action in the PRWL. His lifetime average in his homeland was .284 with 186 hits in 655 at-bats. He had 25 doubles, 14 triples, nine homers and 79 RBIs; he scored 95 runs.

López was happier playing for Arecibo but found ways to bond with Caguas teammates like youngsters Félix Millán, Jerry Morales, and Willie Montañez, to whom he threw batting practice on off-days, even though Morales was competing for playing time.

He got a phone call from Pedrín Zorrilla, a major baseball figure in Puerto Rico who by then was a Yankees bird dog. Zorrilla heard that the Yankees had received an offer for López’s services from a team in Japan. He sought permission from López to have the Yankees negotiate on the player’s behalf. López asked the Yankees to kindly release him, so he could negotiate his own contract.45

Prior to a 1967-68 Caguas-San Juan game at Hiram Bithorn Stadium, Joe Brown, Pittsburgh Pirates GM, made a surprise visit to the visitors’ clubhouse. Brown introduced himself and told López about a potential incentive to join the Bucs organization at the Triple-A level in 1968. According to Lٌópez, Brown said, “If you have a good year at Columbus, we split the Rule 5 Draft amount—half of $25,000 or $50,000—if you are selected by another team.”46 López replied, “I appreciate you and Roberto [Clemente], but I’m going to Japan.” Brown shook López’s hand and left, but López “was forever grateful to him and Roberto—who must have put in a good word for me—for their kindness.”47

Tsuneo “Cappy” Harada, a Japanese-American, helped López connect with the 1968 Tokyo Orions. The club initially thought Art was Héctor López and asked him if he could play third base. Art López informed Harada he could. “The culture in Japan would not permit them (the Orions) to admit to mistakes,” said López. “I helped them save face.”48 Nevertheless, the Orions put Lopez in right field when he joined the club, realizing he was an outfielder. López enjoyed two weeks of 1968 spring training with the Orions, in Maui. Jim Gilliam and Duke Snider were instructors, thanks to the Orions owner’s friendship with Los Angeles Dodgers executives.

López made history in 1968 as the first Puerto Rican to play pro baseball in Japan. He was the fourth Caribbean player there overall.49 Playing right field for Tokyo, López hit 23 homers. With him in the outfield was George Altman, the team’s other gaijin (non-Japanese or foreigner). Orions manager Wataru Nonin had López’s respect: “To think that he was a native of Hiroshima and yet showed no rancor nor malice towards George [Altman] and me.”50

From then through 1971, López and Altman were Orions teammates and road roommates at Western-style hotels. Altman read late at night and slept late. López, an early riser, agreed that they could have adjoining hotel rooms.

Teams in Japan adhered to a tight schedule. López nearly starved during the initial 1968 season road trip because he and Altman fiddled with chopsticks while their teammates picked up “great food from a huge bowl containing all kinds of fish and meats.” The players ate a mile a minute and the team bus was waiting, and we [Altman and López] had eaten almost nothing. It did not take us long to learn how to use those sticks to perfection!”51

López continued to produce in 1969-1971 for the Lotte Orions—the same franchise but under new ownership. Mr. Nagata, Lotte’s owner, was a good friend of Horace Stoneham, the San Francisco Giants owner. San Francisco played nine 1970 spring training games in Japan, winning just three—it was the first time that a big-league team lost more than they won in Japan.52 López hit a homer off Marichal and went 0-for-4 against Gaylord Perry and his spitball.53

The 1970 season was special. López was voted to two All-Star Games, and he appreciated the fans for doing so. He led off the first with a homer; he excused himself from the second in view of the birth of his fifth child, Christopher.

In addition, Lotte (80-47-3) won the Pacific League title by 10 1/2 games over the Nankai Hawks. Five Orions hit 20 or more homers, including López with 21. However, the Yomiuri Giants (79-47-4), Central League winners, took the Nippon Series, four games to one. Sadaharu Oh and Shigeo Nagashima were Yomiuri icons.

In 1971, Lotte spent part of spring training in Scottsdale, Arizona, working out with and playing against San Francisco. López noted that Altman and country singer Charley Pride, from Mississippi, had served in the U.S. Army together. “He [Pride] practiced with us,” said López. “He loved baseball and looked like a great singer.”54 Pride, as a young man, had played briefly (eight games in all), over three seasons in the minor leagues (1953, 1955, and 1960).

López’s key takeaway from Japan was that “Japanese respect your privacy; space is sacred.”55 After signing post-game autographs, fans let him walk to the train station, staying behind him. He appreciated Japan’s “group mentality over individual” philosophy. From a baseball standpoint, he liked the smaller stadium dimensions, as well as a fundamental difference; two cutoff throws, not one longer throw. This allowed him to play right field more effectively, with less strain on his left arm.

López did a kind deed for singer José Feliciano when the latter was in Tokyo for concerts. Feliciano’s suitcases were lost in transit, but López had his own tailor at the Hotel New Japan and arranged for suits to be made for the singer, a native of Lares, Puerto Rico.56

The 1972 and 1973 Yakult Atoms of Japan’s Central League were López’s last two baseball teams. He enjoyed the Orions more, but Japan, overall, was “immensely glorious.”57 The teams furnished lovely housing for the López family. The four older children attended a private school, and there was no need (or time) for López to play winter ball. George Altman was a “great buddy and a great player.”58 In 2021, Altman reciprocated, saying, “It was great having ‘roomie’ for a teammate—a surprise teammate; they [the Orions] believed they had signed Héctor López instead of Art but it turned out fine.” Altman added that the strike zone in Japan was wider for foreign players than for natives, so he and López had to swing at bad pitches.59

Overall in Japan, López played 750 games during six seasons, posting a .290 average with 116 homers and 401 RBIs.60 While in Japan, Lopez learned some Japanese phrases and slang but did not master the language. López was 36, and still in good shape, but his 1972 and 1973 hitting numbers were down and he was ready for a career change. His attorney wrote a letter to George Steinbrenner, inquiring about employment possibilities with the Yankees, but never heard back from Steinbrenner. However. López’s background in the insurance industry helped him make the proper career transition to the East Coast of the U.S.

López had post-baseball success in banking, insurance, and teaching. In 1974, he directed an Insurance Training School for New York and New Jersey, located in New Jersey.

López kept in touch with the baseball world. He was saddened by Luke Easter’s death on March 29, 1979. He gave Roy White a good recommendation to play in Japan when contacted, and White went on to play three seasons for the Yomiuri Giants. In 1991, López attended former winter league opponent and teammate Ferguson Jenkins’s induction ceremony in Cooperstown, and got a hug after yelling, “Fergie, Fergie” to his friend.

López earned an undergraduate degree in Finance from New Jersey City University in 1999. He went on to get two online Master’s degrees from Capella University in 2005 and 2007, in Curriculum and Instruction.

The marriage of López and Mary ended in 1990. He married Antonia Washington on August 8, 2003. He resides in Orlando, Florida, and stays in touch with his sister, Zoraida, in North Carolina and Chicago. López enjoys watching Turner Classic Movies and reading, with a focus on World War I history.

López received yet another degree—his MBA—from Northcentral University in December 2022. His approach to lifelong learning typifies this man’s mindset as an engaging scholar, successful businessman, and someone who made the most of his athletic ability.

Last revised: December 14, 2022

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Art López for phone interviews plus e-mail responses in March-April 2021, and to George Altman for his memories. Ike Futch furnished López’s contact information. Jack Reed shared insights on the 1964 Richmond Vees. Jorge Colón Delgado provided Art’s PRWL stats.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Bruce Harris and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact=checking team..

Photo Credit

Art López collection

Notes

1 The Yankees signed Vic Power ahead of the 1951 season, but Power was traded away in December 1953 before he could become the team’s first Puerto Rican-born player. Luis Arroyo received that honor after the Yankees obtained him in a 1960 trade.

2 Art López, phone interview with Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

3 López, until December 16, 2020, was the first person born in Mayagüez—founded in 1760—to play in the majors. Negro League players José Antonio Figueroa (1940 New York Cubans); Luis Enrique Figueroa (1946 Baltimore Elite Giants); and Carlos Manuel Santiago (1946 New York Cubans) were born in Mayagüez and preceded López as professionals. They are now defined as big-leaguers following Commissioner Rob Manfred’s statement that raised 1920-1948 Negro Leagues to Major League Status. Luis Enrique “Tite” Figueroa coached López in volleyball circa 1946.

4 Thomas E. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1995), 49.

5 López phone interview, March 13, 2021.

6 López phone interview, March 13, 2021.

7 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

8 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

9 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

10 López phone interview, March 11, 2021.

11 López phone interview, March 15, 2021.

12 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

13 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

14 López phone interview, March 13, 2021. He kept his insurance license during his pro baseball career (1961-1973) and specialized in life and health policies as a licensed insurance broker.

15 López phone interview, March 25, 2021. Fans brought tasty Puerto Rican dishes to these games, e.g., arroz y gandules (rice and pigeon peas). They were festive occasions. By 1960, John Candelaria Sr. was divorced and had moved back to Puerto Rico.

16 López phone interview, March 15, 2021.

17 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

18 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

19 López phone interview, April 15, 2021.

20 Rory Costello, Luis Olmo SABR bio.

21 Tite Arroyo pitched for the 1960-63 New York Yankees, but originally signed with the St. Louis Cardinals. López noted that Arroyo hugged him, years later, at a reunion of Puerto Rican baseball players, in Isla Verde, Puerto Rico.

22 López phone interview, March 25, 2021.

23 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

24 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

25 López phone interview, March 11, 2021.

26 López phone interview, March 11, 2021.

27 López phone interview, March 11, 2021.

28 López phone interview, March 11, 2021.

29 López phone interview, March 25, 2021. Coímbre’s lifetime average in the PRWL was .337, second to Willard Brown’s .350.

30 https://www.elnuevodiario.com.ni/deportes/67570-aqui-cayo-fiero-trabuco/ Accessed April 1, 2021.

31 López phone interview, March 15, 2021.

32 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

33 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

34 https://miscbaseball.wordpress.com/2014/06/05/the-1964-yankees-come-to-richmond-for-an-exhibition-game/ Accessed April 2, 2021.

35 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

36 López phone interview, March 11, 2021. Richmond’s owner was Romeo Champagne. The Vees flew to away games.

37 López phone interview, March 11, 2021.

38 López phone interview, March 11, 2021.

39 https://www.baseball-almanac.com/awards/James_P_Dawson_Award.shtml Accessed April 4, 2021. López was the first player born in Puerto Rico to win it. Rusty Torres (1972), Otto Vélez (1973) and Jorge Posada (1997) were the others as of 2021.

40 López phone interview, March 25, 2021

41 López phone interview, March 11, 2021.

42 López phone interview, March 11, 2021.

43 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

44 https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=lopez-002art Accessed April 4, 2021.

45 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021. There are no records of López playing in the minors, circa 1967, but it appears the New York Yankees had to release him so he could negotiate with the Tokyo Orions.

46 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

47 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

48 López phone interview, March 25, 2021.

49 He followed Cuba’s Roberto “Chico” Barbón (1955-1964 Hankyu Braves, 1965 Kintetsu Buffaloes), Chico Fernández (1965 Hanshin Tigers) and Román Mejías (1966 Sankei Atoms). See Akihiro Kawaura and Sumner La Croix, “Integration of North and South American Players in Japan’s Professional Baseball Leagues.” International Economic Review, Vol. 57, No. 3, 2016: 1110. The author did additional research to confirm López was the first Puerto Rico-born player in the Japanese League.

50 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

51 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

52 https://www.nytimes.com/1970/03/30/archives/giants-end-japanese-trip-with-6th-loss-in-9-games.html Accessed April 5, 2021.

53 López phone interview, April 9, 2021.

54 López phone interview, March 25, 2021.

55 López phone interview, March 25, 2021.

56 López phone interview, March 25, 2021. López, as a member of the New York Yankees, first met Feliciano in 1965.

57 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

58 E-mail, Art López to Tom Van Hyning, March 13, 2021.

59 Telephone interview, George Altman with Tom Van Hyning, April 20, 2021. Coincidentally, Tony Castaño, Altman’s manager with the 1959-60 Cienfuegos Elephants in Cuba, managed López with 1963-64 Arecibo.

60 López’s 116 home runs in Japan are fourth all-time for Puerto Rican players, behind Leo Gómez (150), Tommy Cruz (120) and Carlos Ponce (119). Neftali Soto hit 109 through 2020.

Full Name

Arturo López Rodriguez

Born

May 8, 1937 at Mayaguez, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.