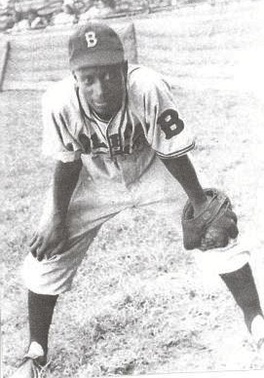

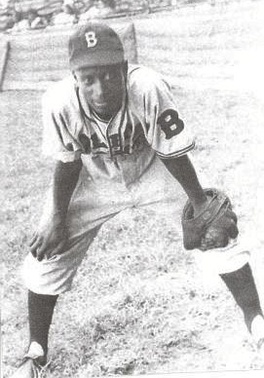

Tommy Butts

Tom Butts stood 5-feet-8 and weighed just 142 pounds, but his size was not the reason he acquired the nickname Pee Wee. Rather, the strong-armed shortstop’s defensive prowess reminded observers of his White contemporary, Pee Wee Reese.1 “I’d compare Butts with Reese or [Phil] Rizzuto or anyone I’ve seen in the big leagues,” opined Roy Campanella, a former teammate of both Butts and Reese. “Butts could do everything. He just didn’t get the opportunity to do it in the majors.”2

Tom Butts stood 5-feet-8 and weighed just 142 pounds, but his size was not the reason he acquired the nickname Pee Wee. Rather, the strong-armed shortstop’s defensive prowess reminded observers of his White contemporary, Pee Wee Reese.1 “I’d compare Butts with Reese or [Phil] Rizzuto or anyone I’ve seen in the big leagues,” opined Roy Campanella, a former teammate of both Butts and Reese. “Butts could do everything. He just didn’t get the opportunity to do it in the majors.”2

Butts, known as “Pea Eye” in his hometown, was one of the Negro Leagues’ outstanding shortstops, selected for East-West All-Star Games in eight years between 1942 and 1953.3 During his 11 seasons with the Baltimore Elite Giants, the club won the 1939 Negro National League II (NNL2) championship, and the 1949 Negro American League (NAL) title.

Thomas Lee Butts was born on August 27, 1919, in Sparta, Georgia. His parents, Asbury and Mollie (Eagle) Butts, already had a son, Robert. Sparta, about 100 miles southeast of Atlanta in Hancock County, had fewer than 2,000 residents, and Asbury labored on a farm. Asbury’s grandfather Berry had been enslaved in the same county.4 By the 1930 census, Tom’s family, including his younger sisters, Anna and Christine, had moved to Atlanta, where his father worked at a packing plant.

In the summer of 1935, the Atlanta Daily World noticed the 15-year-old Butts with the semipro Atlanta Red Caps. The newspaper noted, “Butts … played a sensational brand of ball at second sack and time and time again brought the fans to their feet in wild acclaim for some startling catch or throw.”5 Years later, after Butts made his mark in professional baseball, the paper recalled his teen gridiron exploits, reminding its readers, “His feats in football, according to the story tellers, were in the class of John Bunyan, Johnny Appleseed, Achilles, Alexander and other unbeatables of fact and fiction.”6

In 1935, Butts’ last year at David T. Howard Junior High School, he was named Atlanta’s second team All-City quarterback. (Howard’s coach and athletic director, “Chicken” Charlie Clark, had pitched in the Negro Leagues.7) Butts’ brother, Robert, a center at Booker T. Washington High School (BTWHS), made the first team.8

The taller Robert – 5-feet-11, according to military records – was an outfielder when he and Tom played baseball for the 1936 Red Caps.9 That fall, the brothers were football teammates at BTWHS. Robert was nicknamed “Pea Eye.” The local press occasionally confused the two brothers for one another.

Pea Eye remained a football star at BTWHS, leading the Bulldogs to the 1937 Southeastern Inter-Scholastic championship as a sophomore.10 One of his performances earned him praise as “a coach’s dream” and “the canny little triple-threated field general.”11 His future was in professional baseball, though. After his hometown Atlanta Black Crackers started slowly in 1938, he joined the NAL club in June.

On July 1, the Daily World hailed Tom Butts, 18, as “one of the most discussed youngsters in the game,” noting, “He was called the greatest shortstop to appear in Memphis thus far in 1938. He made impossible chances look quite easy.”12

Butts recalled years later how his teammates reacted after one opposing player knocked him down with a hard slide: “That started a rhubarb because they all wanted to protect me. I was sort of the prize star, and I was younger, too.”13

During an August sweep of the league’s first-half champion Memphis Red Sox, the Daily World reported, “In the opening game, (Butts) tripled to left center to score Red Moore and injected more life and spirit in the Atlanta team. During the same series, he made a perfect throw to Joe] Greene at the plate to nab Cowan] Hyde and cut off a run.”14

Atlanta won 11 consecutive games to clinch the NAL’s second-half title.15 The first two games of the best-of-seven championship series were to be played in Memphis, the third in Birmingham, Alabama, and Game Four was scheduled to be “Butts’ Night” in Atlanta.16

Atlanta lost the opener, 6-1, but Butts scored their only run and notched one of their five hits against Ted Radcliffe.17 After the Black Crackers lost the second contest, 11-6, bad weather canceled the September 20 game in Birmingham.18 Because the (White) Atlanta Crackers were hosting the Class A-1 Southern Association finals, Ponce de Leon Park was unavailable on Wednesday and Thursday, and a high-school football game was booked there on Friday.19 The NAL playoffs were postponed until a Sunday doubleheader, but the Daily World noted, “Plans for Butts’ Day are still going along smoothly and his classmates at Booker Washington high are rallying behind the idea to make the young phenom supremely happy.”20

On Friday afternoon, Butts quarterbacked BTWHS to a 28-6 victory over Tuskegee High.21 However, the same page of the newspaper that described the action reported that the NAL championship series would not resume. It was noted that “[t]he Red Sox feel that they cannot win in Atlanta and that they won’t be treated ‘right.’ Thus they disbanded and are scattered to the wind by the decree of their owner.”22 To recover some revenue, the Black Crackers swept an otherwise meaningless twin bill from the Birmingham Black Barons.23 At the NAL meeting in December, the Red Sox were officially declared the champions.24

The following spring, journalist Ric Roberts observed, “Watching [Butts], you get the idea that before your very eyes cavorts a real ball player. 5,000 youngsters come and go for every single Butts.”25

The Black Crackers agreed to have a second “home” city in 1939 – closer to most of their Midwest-based NAL opponents. As part of the deal, they would play as the Indianapolis ABC’s.26 But while the team was on the season-opening road trip, club owner John Harden learned that they would not be permitted to use the ballpark in Indianapolis, so he shifted operations back to Atlanta before the June 14 home opener.27 A June 21 headline read “Black Crax No Longer Indianapolis ABC’s.”28 But the June 26 Daily World reported, “Black Crax Out of Negro American League.” At the NAL’s midseason meeting, a majority of the other owners voted to expel Harden’s team for failing to play as the ABC’s.29

Less than two weeks later, the Baltimore Elite Giants of the NNL2 announced that they had acquired Butts and four of his teammates: first baseman Moore, catcher Oscar Boone, and pitchers Ed Dixon and Felix Evans.30 “We got on the train to Baltimore that night, and that was one of the biggest thrills I ever had,” Butts said. “Big town, big buildings – at the time Atlanta didn’t have anything like that.”31

On July 9 at Oriole Park, Butts debuted in the Elites’ doubleheader sweep of the Philadelphia Stars.32 He recalled that he made three throwing errors and admitted feeling nervous to manager-third baseman Felton Snow. “[Snow] said, “‘Aw, come on, “Cool Breeze” – that’s where I got the name of Cool Breeze, right there – ‘don’t be nervous, you can do it.’ He gave me a big lift there.”33

Butts roomed with Roy Campanella, a 17-year-old catcher whom he called “Pooch.” “[Campanella] was a talker,” Butts said. “You know, you just can’t go to sleep. … He would talk me to sleep.”34

When the Elite Giants played in the Deep South in early August, an Atlanta paper explained, “Butts is not on the present road trip. His leg is in a cast[,] and he is with Negro National League President (and Elites owner) Tom Wilson’s home in Nashville. … The classy young shortstop was injured in sliding in a game against a white team last week.”35

Butts was back in action by August 13, when he went 3-for-5 with a stolen base in Baltimore’s 11-1 victory over the New York Cubans at Yankee Stadium.36 Yankee Stadium “looked like a hotel from the outside, it didn’t look like a baseball park,” he said. “But after all these bad fields, that was a good one. And after that, every time they said New York, I was ready.”37

The Elites qualified for the NNL2’s semifinal playoffs and beat the Newark Eagles, three games to one. Baltimore advanced to the championship series but dropped the opener, 2-1, to the Homestead Grays in Philadelphia. The Grays’ second run scored when Butts juggled a potential first-inning-ending double-play grounder off the bat of Buck Leonard and recorded just one out.38 The Elites won the next three contests and finished off the Grays with a 2-0 victory at Yankee Stadium on September 24. Butts batted .333 (5-for-15) in the series. After he posed alongside the Ruppert Cup trophy with his teammates, he appeared in the game between NNL2 players and White minor leaguers later that afternoon.39

Baltimore placed second behind the Grays in 1940. In 55 official NNL2 games, Butts hit .284, with 44 runs scored and 34 RBIs. His 4-for-4 performance in the second game of a July 28 doubleheader at Yankee Stadium helped the Elites defeat the Grays, 15-6, and evidenced his development as a hitter.40 Butts credited veteran George Scales, who had returned to the Elites that season. “The more you swing, the less you hit the ball. You just get on base, walk, anything,” he recalled Scales saying. “I choked up on my bat, cut down on my swing, and started to get those hits.”41

Scales also helped the shortstop to improve his defense. Butts explained, “George Scales was a great teacher … a little hard on you, but if you’d listen you could learn a lot. I used to have trouble coming in on slow balls. … He drilled me until I finally caught on to it.”42

Prior to the 1941 campaign, one writer observed, “Tommy Butts … was rated the top shortfielder in the league on the All-NNL team for 1940. … He has a magnificent pair of hands, a great arm and is improving constantly as a hitter.”43 That summer, he was called Pee Wee for the first time in print.44 It was an homage to future Hall of Famer Pee Wee Reese, who was in his first season as a full-time Brooklyn Dodgers starter.45

Although Butts batted just .185 in 59 official games in 1941, he edged out the New York Cubans’ Horacio Martínez as the first-team shortstop on Cum Posey’s 18th annual All-American baseball team. “Butts can now be placed in a class with Jake Stevens [sic], Dick] Lundy, Willie] Wells and other greats,” Posey wrote.46

Following a fight between fans after the Elites’ 1942 home opener that caused minor damage to Oriole Park, the team lost access to the facility, and Bugle Field became their primary home ballpark.47 “The infield was so rotted that shortstop Pee Wee Butts once took a bad hop between the eyes, called time, picked up the ball and heaved it over the left-field fence,” noted a Baltimore Sun retrospective.48 Butts said, “I used to go out myself and look for bad spots before I’d start playing. The ground was pretty bad, just a little too sandy.”49

Butts helped the Elite Giants beat the Grays, 1-0, at Bugle Field on July 10. His seventh-inning RBI single off Roy Partlow produced the only score, and his ninth-inning throw cut down the potential tying run at home plate. With two runners on and one out, a drive by the Grays’ Ray Brown hit a high-tension wire above the diamond and caromed to Baltimore center fielder Henry Kimbro. Butts’ relay to catcher Bob Clarke nailed Josh Gibson attempting to score from second base, and Baltimore sealed the victory one batter later.50

When right-hander Leon Day of the visiting Newark Eagles struck out 18 Elites on July 31,1942, Butts’ leadoff single was the only hit allowed by the future Hall of Famer.51 That summer Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis insisted that the White majors had no rule prohibiting teams from signing Black players. Detroit-based sportswriter Russ Cowans had already named Butts among the 10 Negro Leaguers (and others) who could help big-league teams.52 Grays manager Vic Harris also included Butts on his list of NNL2 stars who could likely succeed in the majors.53 The New York Daily News reported, “[Butts] is another Pee Wee Reese – except that he hits better. He gets the ball away fast and has a terrific whip, sometimes throwing men out from behind third base.”54 Butts was an East squad reserve for the prestigious East-West All-Star Game at Comiskey Park, but he did not see action.55

Heading into a pair of season-ending doubleheaders against Philadelphia, the Elites had a chance to win the NNL2 pennant and meet the NAL champion Kansas City Monarchs in the revived Negro World Series. But Baltimore split both twin bills and finished behind the Grays.56 The Elites’ chances were hampered by the absence of Campanella, who had jumped to a team in Mexico.57

When Campanella remained in the Mexican League in 1943, Butts joined him in the Industriales de Monterrey’s lineup. The team finished with a league-best 53-37 record. Butts teamed with Cuban second baseman Herberto Blanco up the middle and batted .248 with one homer and nine steals in 80 games.

In 1944 Butts and Campanella were both back with the Elite Giants. As the East-West All-Star Game approached, Sam Lacy of the Baltimore Afro-American wrote, “The brilliant Tommy Butts of the Baltimore Elite Giants can easily be the choice for the shortstop berth, mainly because he is just about the cleanest fielding infielder in Negro baseball at the moment and, too, because there is no better sacrifice man around than the Georgia cracker-jack.”58 (Three years later, Lacy reported, “Pee Wee Butts hates to be called Tommy.”59) With 46,247 in attendance at Comiskey Park on August 13, Butts started and went 0-for-2 in the East’s 7-4 defeat.60

After the Grays retained their NNL2 championship. Butts went to the Puerto Rican Winter League in 1944-45 and hit .237 in 76 at-bats with the Indios de Mayagüez.61

During training camp before Baltimore’s 1945 campaign. Butts underwent an appendectomy.62 He soon returned to action, but he was not selected for the East-West All-Star Game for the only time in a seven-season (1944-1950) span. The Elites also failed to dethrone the Grays. That fall the Elites increased their winning streak against the White Baltimore Orioles of the International League to six consecutive games. Butts keyed a 3-1 victory with a first-inning RBI triple against Walt Masterson, a righty with big-league experience whom the Orioles had brought in to pitch the October 7 contest.63

Sixteen days later, the Brooklyn Dodgers signed Negro League infielder Jackie Robinson to a minor-league contract. Although Robinson received most of the headlines for his play with their International League affiliate in Montreal in 1946, Brooklyn also signed three other African Americans that offseason. Pitcher Johnny Wright spent the bulk of the season with Class-C Trois-Rivieres, Quebéc, while Campanella and right-hander Don Newcombe played for the Dodgers’ Class-B farm club in Nashua, New Hampshire.

The Newark Eagles, featuring future Hall of Famers Larry Doby and Monte Irvin, won the 1946 NNL2 pennant and Negro World Series. Butts earned a return to the East-West All-Star Game with his best season to that point: .315 with 7 triples in a league-leading 64 games. That fall the Afro-American said an exhibition against a team of major-league all-stars would be “Kimbro-Butts Day,” noting, “Baltimoreans will do a long-delayed honor to the Elites’ most diligent pair of workmen.”64

In 1947 Butts produced his personal best slash line: .351/.391/.459 in 59 games. “I never was a curve ball hitter, but if someone tried to sneak a fast ball, I’d get a little hit,” was how he described his approach. “They always said I hit high balls. They said I hit them off my cap bill.”65 He was elected to start the East-West All-Star Game and went 0-for-2 in front of 48,112 and “a galaxy of major league scouts” in attendance at Comiskey Park.66

Butts played winter ball in Cuba for the Alacranes del Almendares in 1947-48.67 “Adolph Luque in Cuba rated Butts even better than Rizzuto,” recalled Lennie Pearson, another Negro Leaguer who played in the Cuban circuit. Pearson added, “He could go behind second base better than any man I ever saw in my life.”68 Butts also impressed former major-league catcher and coach Mike González, the manager of the champion Leones del Habana. The Baltimore Afro-American reported, “Gonzales [sic] said that Butts is the ‘best I’ve ever seen’ and the old National Leaguer has seen most of the top flight performers.”69

Although the Negro Leagues had lost more players to the formerly segregated majors by the summer of 1948, Philadelphia Stars manager Oscar Charleston opined, “There is still plenty of big league material left, like Tommy Butts.”70 One of the circuit’s budding stars was Butts’ double-play partner, second baseman Junior Gilliam, who had joined the Elite Giants as a 17-year-old in 1946. “I don’t know what kind of credit Junior Gilliam might give anybody, but Butts worked with him just like he was his own son and developed him into one of the top infielders in the Negro National League,” remarked one opponent, Chico Renfroe.71

“Gilliam was a quiet guy, but when he got on the field he had more pep than you’d think he had. He could make a team go. … He was really a baseball nut,” said Butts. Although he insisted that Scales deserved recognition for making Gilliam a switch-hitter and second baseman, Butts acknowledged. “[Gilliam] was a little younger than I was, and the fellows told me to keep my eye on him, don’t let him go running around.”72

During Butts and Gilliam’s second full season as a keystone duo in 1948, Lacy wrote, “Both are timely hitters if not great hitters. Both are fast, aggressive base-runners and offer serious threats to the opposition whenever they’re on the base-paths. Between them, they have four of the best hands in baseball and their throwing arms, particularly Butts’s, are not to be toyed with.”73 Baltimore advanced to the NNL2 championship series but lost to Homestead.

In June, Butts had been suspended for 10 days and fined $100 by NNL2 President John H. Johnson after an uncharacteristic incident at Yankee Stadium on May 30, 1948.74 After Butts’ liner to left field was caught on one hop by New York Cubans left fielder Cleveland Clark, umpire Julio Hernández ruled it a clean catch. Incensed, Butts struck the umpire twice – knocking him down – and jumped on him. “This marks the first time [Butts] has ever been in a dispute with an umpire,” reported the Afro-American. “A quiet personality, he seldom takes issue with an umpire’s decisions, despite the fact that teammates say there any many occasions when he would be justified in doing so.”75

There is no evidence that the incident hampered Butts’ major-league prospects.76 That summer Lacy wrote, “Had he been fortunate enough to possess about 10 more pounds, Butts would have been one of the first NNL players sought by the major league outfit. But with only 146 pounds on his frame – wringing wet – Butts is much too small to serve effectively as a major league shortstop. This, to the writer’s way of thinking, and this alone has kept him from being a big league player today.”77

In the 80-game 1948-1949 Puerto Rican Winter League campaign. Butts hit .312 with 61 runs scored for the Cangrejeros de Santurce.78 That team also lost in the championship series.

The NNL2 ceased operations before the 1949 season, but the Elite Giants joined the NAL and carried on. Before the Chicago White Sox signed White infielder Jim Baumer to a $50,000 “bonus baby” contract on June 2, White Sox GM Frank Lane inquired about Butts.79 Another report said a Triple-A Pacific Coast League club expressed interest but signed Parnell Woods instead because the Elite Giants wanted too much money.80 Butts remained with Baltimore, started another East-West All-Star Game, and led the circuit’s shortstops in fielding.81 Unlike many of his contemporaries, who left their gloves on the field when their team was at bat, Lacy noted, “Butts … is superstitious, he … carts it all the way to the front of his dugout.”82

The Elite Giants swept the Chicago American Giants in four games to win the 1949 NAL title. The clinching 4-2 victory at Comiskey Park was scoreless until the top of the sixth inning, when Butts led off with an opposite-field single and scored on Lennie Pearson’s double.83

After hitting just .221 in 280 at-bats for Santurce in winter ball, Butts returned to Baltimore in 1950 for what proved to be his final season with the Elite Giants. Bugle Field had been demolished, so Opening Day marked the first game between two Black teams at Memorial Stadium. Butts walked and scored twice against Philadelphia, including the decisive run in the bottom of the ninth on Gilliam’s RBI.84 Butts was elected an East-West All-Star Game starter again, but his Elite Giants career ended on September 3 when he was one of four players suspended by manager Kimbro before the club’s home finale. Although their teammates had voted to accept business manager Dick Powell’s proposal to remain on salary through Labor Day, Butts and three others refused to dress unless they received a percentage of the gate instead.85

Butts played for the Winnipeg Buffaloes of the semipro Manitoba-Dakota (ManDak) League in 1951. The team, managed by future Hall of Famer Willie Wells, was defeated in the circuit’s championship series. “I didn’t want to go back, it was too cold up there,” Butts said.86

In 1952 three former Elite Giants – Butts, pitcher Al Wilmore, and second baseman Fleming Reedy – became the Philadelphia Athletics organization’s first African American players.87 Butts and Wilmore were signed by scout Judy Johnson.88 After spring training in Savannah, Georgia, the trio was assigned to the Lincoln (Nebraska) A’s in the Class-A Western League. (Reedy lasted 11 seasons in the minors, but arm problems derailed Wilmore.) Butts hit just .170 in 47 games. When Lincoln tried to demote him to Class B that summer, Butts returned to the NAL instead. Later, he explained that he could tell his skills were slipping, and he did not think it would be fair to block a younger player.89 Butts joined the Birmingham Black Barons and saw action in the 1952 NAL championship series, won by the Indianapolis Clowns club that featured 18-year-old shortstop Henry Aaron.90

Gilliam debuted with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1953 and won the National League Rookie of the Year Award. “It broke Butts up when Gilliam went up to the big leagues and he didn’t,” said Pearson. “He wasn’t too old for the majors. But he loved life, and when I say he loved life, I mean he loved life, especially women. After a game, Butts had a tendency to go off on the town, while Gilliam would stay around and listen to the old-timers talk and soak up that knowledge of baseball.”91

Although Butts was voted a starter for one final East-West All-Star Game that summer, when the Black Barons played in Atlanta, the Daily World observed, “Good living, good time, good pay have taken their toll on Butts. He is now in the twilight of a brilliant career. … The shuddering hardships of barnstorming competition have wrecked the splendid promise.”92

In 1954 Butts saw action with the Black Barons and the Memphis Red Sox. In 1955 he appeared in 28 games in the Class-B Big State League, batting .265 for the Texas City Texans. Three of Butts’ former Baltimore teammates contributed to the Brooklyn Dodgers team that won its only World Series that fall. Pitcher Joe Black won his only decision before he was traded in June, Gilliam started at second base, and Campanella was the NL MVP.

A 1960 Atlanta directory listed Butts as a helper for a metal fabrication company. He married Dorothy Butler, a Baltimorean, and fathered four children: Jean, Thomas, Retta, and Norma.93

When Negro Leagues historian John Holway interviewed him in 1970, Butts said attending an old-timers’ game in Atlanta the previous year had been “a big thrill.”94 Butts described reuniting with Johnny Logan, a former Puerto Rican League teammate who told him that he still appeared to be in shape. “Yeah, I’m in shape, but I can’t do anything now,” he replied. Butts also shared how he had visited Campanella in New York since a January 1958 car accident had left his old roommate paralyzed.95

Tom Butts was 53 when he died on December 30, 1972, in Atlanta. He is buried in the city’s South-View Cemetery, the final resting place for many prominent African Americans, including civil rights icons Julian Bond and John Lewis, sports greats Henry Aaron and Walt Bellamy, and Martin Luther King Sr.

Joe Black named Butts the first-team shortstop on his all-time Black all-star team in 1969.96 Later, Black reflected, “Players like Leon Day, Pee Wee Butts, Larry Doby, Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, those guys could play. … They had credentials for the Hall of Fame.”97 When Black uttered those words in 1992, only Gibson and Leonard had been enshrined in Cooperstown, but Butts was the only player he named who had not been so honored as of 2024.

“If I’d been 10 years younger, I think I could have made the major leagues,” Butts told Holway. “If the doors had opened up a little earlier, I think I’d have done pretty good.”98

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com, www.retrosheet.org, https://sabr.org/bioproject, and https://seamheads.com/blog/.

Tom Butts’ Puerto Rican Winter League statistics are from https://beisbol101.com/jugador/tommy-butts/

Notes

1 Tom Holcomb, “‘We Were Trailblazers for Jackie Robinson,’” Atlanta Constitution, June 27, 1997: E7.

2 John Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues (New York: Da Capo Press, Inc. 1992), 327.

3 In addition to Butts’ four East-West All-Star Game seasons (1944, both 1946 contests, 1947, 1948) reflected by Baseball Reference in March 2023, he was a reserve – but did not play – in the 1942 contest. Butts also started East-West All-Star Games in 1949, 1950, and 1953, but the post-1948 Negro Leagues were not retroactively deemed major leagues.

4 In a 1937 “Ex-Slave Interview” for the Federal Writers Project, Berry’s sister Carrie said her family had labored on Ben Bass’s plantation. (According to military records, Bass’s Confederate Army unit surrendered with General Robert E. Lee’s forces at Appomattox Court House in Virginia in 1865.) After gaining their freedom, Carrie described how they initially remained there as low-wage workers before moving from farm to farm as renters. Aunt Carrie Mason, “Ex-Slave Interview” written by Estelle G. Burke, Federal Writers’ Project July 7, 1937, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/6227:1944?ssrc=pt&tid=171658784&pid=362378020616. (Subscription service, last accessed February 26, 2023).

5 Sam McKibben, “Atlanta Red Caps Take 5-1 Slugging,” Atlanta Daily World, July 27, 1935: 5.

6 Marion E. Jackson, “Sports of the World,” Atlanta Daily World, June 19, 1953: 7.

7 Ric Roberts, “‘Chicken’ Charlie Clark Affords Real Story for Ambitious Young Men,” Atlanta Daily World, August 9, 1936: 2.

8 Sam McKibben, “McKibben Lists All City Prep Eleven,” Atlanta Daily World, December 8, 1935: 5.

9 Sam McKibben, “Semi-pro Outfits to Commence Activities,” Atlanta Daily World, May 4, 1936: 5.

10 “‘Pea-Eye’ Butts Will Be Honored by BTWHS Folk,” Atlanta Daily World, September 16, 1938: 5.

11 Lucius Jones, “Atlanta Preps Wins Brilliant ‘Intersectional’ Tilt, 29-13,” Atlanta Daily World, December 5, 1937: 1.

12 “BTWHS Grid Star, Butts, Newest Black Crax Phenom,” Atlanta Daily World, July 1, 1938: 5.

13 Holway, 331.

14 “‘Pea-Eye’ Butts Will Be Honored by BTWHS Folk.”

15 “Black Crackers Clinch Second Half Pennant,” Atlanta Daily World, September 9, 1938: 11.

16 “Butts Night to Honor Black Crax Star,” Atlanta Daily World, September 18, 1938: 8.

17 “Memphis Leads in Playoff for Championship,” Chicago Defender, September 24, 1938: 8.

18 Scott News Syndicate, “Bad Weather Prevents Third Game,” Atlanta Daily World, September 21, 1938: 5.

19 Roy White, “Purples Meet Monroe Aggies Friday Night,” Atlanta Constitution, September 21, 1938: 10.

20 “Black Crackers to Face Memphis at Ponce de Leon Sunday, Sept. 25,” Atlanta Daily World, September 21, 1938: 5.

21 “4,000 See BTWHS Rip Tuskegee High, 28-6,” Atlanta Daily World, September 24, 1938: 5.

22 “Sunday Set Aside as Day to Help Our Black Crax Boys,” Atlanta Daily World, September 24, 1938: 5.

23 “Black Crax Nip Black Barons in Pair, 5-3, 4-3,” Atlanta Daily World, September 26, 1938: 5.

24 “Memphis Gets 1938 American League Pennant,” Chicago Defender, December 17, 1938: 9.

25 Ric Roberts, “Shortstop Thomas Butts,” Atlanta Daily World, March 24, 1939: 5.

26 Louisville was the initial city the Black Crackers agreed to represent, but they settled on Indianapolis after securing the use of a ballpark in Louisville became an issue. Scott News Syndicate, “Atlanta Changed Hands,” Atlanta Daily Work, May 10, 1939: 5.

27 Lucius Jones, “Black Crax Win, 2-0; Show Again 3 p.m.,” Atlanta Daily World, June 15, 1939: 5.

28 “Black Crax No Longer Indianapolis ABC’s,” Atlanta Daily World, June 21, 1939: 5.

29 Lucius “Melancholy” Jones, “Black Crax Out of Negro American League,” Atlanta Daily World, June 26, 1939: 5.

30 “Five Atlanta Players Signed by Baltimore,” Chicago Defender, July 22, 1939: 8.

31 Holway, 332.

32 “Elites Take Lead in Second Half,” Afro-American, July 15, 1939: 21.

33 Holway, 332.

34 Holway, 329.

35 Holway, 332.

36 “Metropolitan Teams Bow in Double Bill,” Norfolk (Virginia) New Journal and Guide, August 19, 1939: 19.

37 Holway, 333.

38 “Partlow Bests Byrd as Grays Win Opener, 2-1,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 23, 1939: 1.

39 “Baltimore Whips Homestead Grays for Title,” Chicago Defender, September 30, 1939: 9.

40 Art Carter, “Elites, Grays Split Double-Header,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 3, 1940: 19.

41 Holway, 333.

42 Holway, 333.

43 Ed Perry, “Cash Lures Big League Overlords,” Norfolk New Journal and Guide, April 19, 1941: 13.

44 “Baltimore Elites Only Club to Beat Bushies Twice, Play,” New York Amsterdam Star-News, July 19, 1941: 18.

45 Holcomb, “‘We Were Trailblazers for Jackie Robinson.’”

46 Cum Posey, “Posey’s 18th All-American Baseball Team,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 25, 1941: 17.

47 Robert V. Leffler Jr., “The History of Black Baseball in Baltimore from 1913 to 1951,” master’s thesis, Morgan State University, 1974: 87. Cited in Bob Luke, The Baltimore Elite Giants (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 70.

48 Bill Glauber, “Elite Giants: The Pride of Baltimore Baseball History,” Baltimore Sun, April 29, 1990: 1A.

49 Holway, 332.

50 Art Carter, “Gaines Hurls 4-Hit Ball as Grays Are Blanked, 1-0,” Afro-American, July 11, 1942: 22.

51 “Elites Drop 3 Straight as Grays Take Twin Bill,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 1, 1942: 23.

52 Russ J. Cowans, “Sports Chatter,” Michigan Chronicle (Detroit), June 6, 1942: 16.

53 Ric Roberts, “Vic Harris Says Build Own Baseball Leagues,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 8, 1942: 23.

54 Lester Rose, “Major Prospects,” New York Daily News, August 16, 1942: 34.

55 “Negro East-West Game Today May Attract 40,000,” Chicago Tribune, August 16, 1942: B2. Another account published the previous day suggested that Butts could see action. Associated Negro Press, “Pea Eye Butts May Get Try,” Phoenix Index, August 15, 1942: 6.

56 “Grays Win NNL Flag; Play K.C.’s,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 12, 1942: 23.

57 “Roy Campanella Jumps Elite Giants; Said to be Playing in Mexico,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 12, 1942: 14.

58 Sam Lacy, “Looking ’Em Over,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 5, 1944: 18.

59 Sam Lacy, “From A to Z,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 13, 1947: 12.

60 Harold Jackson, “46,000 See West Win All-Star Classic, 7-4,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 19, 1944: 18.

61 “Tommy Butts,” Béisbol 101, https://beisbol101.com/jugador/tommy-butts/ (last accessed March 13, 2023).

62 “Baltimore-Black Yankees at Stadium Sunday,” New York Amsterdam News, May 19, 1945: 8B.

63 The article describes Butts’ hit as a triple, but it is recorded as a double in the box score. “Orioles Humbled 3-1, 4-3 by Balto. Elite Giants,” Baltimore Afro-American, October 13, 1945: 22.

64 Sam Lacy, “Looking ’Em Over,” Baltimore Afro-American, October 12, 1946: 17.

65 Holway, 333.

66 “West’s 5-2 Win Makes It 3 in a Row Over the East,” Norfolk New Journal and Guide, August 2, 1947: 14.

67 “Negro Leaguers in Cuban Winter League,” Center for Negro League Baseball Research, http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/RL/Negro%20Leaguers%20in%20Cuban%20Winter%20League.pdf (last accessed March 18, 2023).

68 Holway, 327.

69 “Giants Seek Local Player, Bid Aspirants to Try Out,” Baltimore Afro-American, April 17, 1948: 27.

70 Norvin (Rip) Collins, “Still ‘Plenty of Negro Baseball Prospects,” Wilmington (Delaware) Journal-Every Evening July 14, 1948: 28.

71 Holway, 328.

72 Holway, 335.

73 Sam Lacy, “NNL’s Keystone Kuties Bonded by Close Friendship,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 4, 1948: 8.

74 Scott News Syndicate, “Negro National League Meeting Set for June 23,” Atlanta Daily World, June 12, 1948: 5.

75 Sam Lacy, “Butts Suspended, Fined $100 for Fight,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 5, 1948: 9.

76 In an August 2023 note to the author Frederick Bush added that Philadelphia Stars catcher Bill Cash likely didn’t make it into what was then considered Organized Baseball because of his run-in with an umpire in Leon Day’s Opening Day no-hitter earlier that season. Owners like Effa Manley and reporters like Wendell Smith were convinced that such behavior was detrimental to a player’s chances at playing in the minors or majors.

77 Lacy, “NNL’s Keystone Kuties Bonded by Close Friendship.”

78 “Tommy Butts.”

79 Sam Lacy, “From A to Z,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 11, 1949: C4.

80 The article identifies the PCL team as the San Diego Padres, but Woods signed with Oakland Oaks. Wendell Smith, “Louis Made Writers Look Good,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 18, 1949: 22.

81 “Lenny Pigg Officially Designated Champion Batter of the NAL,” Chicago Defender, December 24, 1949: 14.

82 Sam Lacy, “From A to Z,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 10, 1949: 16.

83 R.S. Simmons, “Elite Giants Sweep Series for American League Championship,” Atlanta Daily World, September 28, 1949: 5.

84 “10,000 Watch Elites Open NAL Season,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 13, 1950: 18.

85 The players suspended with Butts were John Coleman, Ed Finney, and Al Wilmore. “Ban 4 Elites After Strike,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 9, 1950: 17.

86 Holway, 337.

87 Bill Bowens, “Three Former Elite Giants Crack Tradition in Georgia,” Baltimore Afro-American, April 19, 1952: 16.

88 Al Cartwright, “Judy Johnson Catches Two for A’s,” Wilmington Journal-Every Evening, March 7, 1952: 21.

89 Holway, 337.

90 “Flags Fly and So Do Fists at Negro League World Series,” Philadelphia Tribune, October 7, 1952: 10.

91 Holway, 328.

92 Jackson, “Sports of the World.”

93 “Funeral Notices,” Atlanta Constitution, January 5, 1973: 6C.

94 Holway, 328.

95 Holway, 328.

96 Joe Black, “Ex-Dodger Joe Black Picks All-time All Star Black Team,” Chicago Defender, August 9, 1969: 45.

97 Tom Haudricourt, “Negro League Players Get Overdue Tribute,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 19, 1992: 6B.

98 Holway, 329.

Full Name

Thomas Lee Butts

Born

August 27, 1919 at Sparta, GA (USA)

Died

December 30, 1972 at Atlanta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.