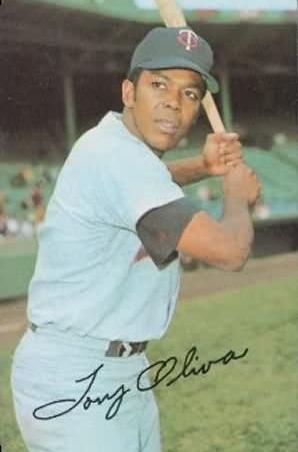

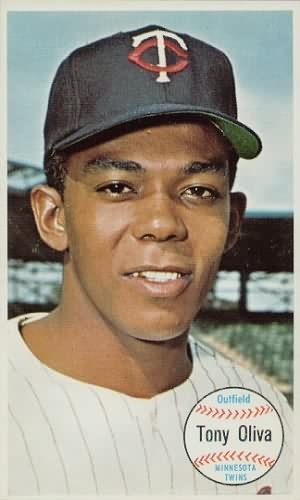

Tony Oliva

Tony Oliva stands at the forefront of an exceedingly select group – one that also includes Tany (Atanasio) Pérez, Rafael Palmeiro, and Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso. These are the few unrivaled candidates for recognition as the greatest major-league hitter ever to emigrate to the professional big time from the baseball-rich island nation of Cuba. Palmeiro (with 569 long balls in 2,831 games) and Pérez (379 in 2,777 games) far outstripped Oliva (220 in 1,676 games) in big-league career homers; Miñoso (playing 159 more games) also would register a marginally more lofty career base hit total (1,963 to 1,917). But Oliva was the only one of the stellar quartet to claim a league batting title (which he did on three occasions); five different times Oliva also paced a big-league circuit in base hits, a feat never achieved by Pérez and accomplished only once by Miñoso and Palmeiro. And only Oliva retired with a lifetime batting average still above the .300 high-water mark.

If raw career power numbers amassed by the other three (and also by José Canseco, with 462 homers and 1,407 RBIs) notably outstrip those in Oliva’s resume, an easy explanation is found in the significant differences in total seasons and total games logged on the big-league diamond. Reduce the career of each Cuban star to a single 162-game lifetime average, and the differences between them become rather too close to adequately distinguish one from the other. Oliva leads the pack in two categories (185 hits and a .304 BA); his average of 21 home runs nearly matches Pérez (at 22) and is outdistanced only by Palmeiro (at 33); his 92 yearly RBI average total edges Miñoso (90), essentially equals Pérez (96), and lags behind only Palmeiro (105).

But such thumbnail comparisons somewhat blunt the true significance of Tony Oliva’s Hall of Fame career. While the Pinar del Río native remained without an official plaque hung in Cooperstown until 2022, his place in diamond history will nonetheless always be easily assured by a memorable collection of early-1960s pioneering awards and achievements. He was the first among his fellow Cuban countrymen to win a big-league batting title and perhaps even more significantly the first big leaguer (Latino or otherwise) ever to capture batting crowns in his initial two seasons.

To add some further luster, Oliva was also the first Cuban to earn Rookie of the Year plaudits in the majors. Among the long list of stellar Latin American imports, only Venezuela’s Luis Aparicio (1956) and Puerto Rico’s Orlando Cepeda (1958) preceded Oliva in claiming the big league top rookie award. And before 1964 (when Oliva topped the junior circuit and Puerto Rico’s Roberto Clemente also paced the senior circuit), only Mexico’s Roberto Avila (1954) and Clemente (1961) among Latinos stars had ever walked off with either an American League or National League batting crown.

If statistics go a long way toward explaining baseball’s endless fascination for some fans, mere numbers always fall far short of elucidating the sport’s unparalleled beauty for true devotees. Thus in the end neither the raw numbers nor celebrated honors quite do sufficient justice to the aesthetics of Pedro “Tony” Oliva’s image as a complete big league ballplayer. The flashy Cuban could simply do it all – hit for superior average, slug with eye-popping power, run like a svelte gazelle, and throw accurately and powerfully from the outfield with the best of them.

Unfortunately, his one great flaw proved to be a set of weak knees that repeatedly folded under the immense stresses of the lengthy summer baseball wars. A series of painful knee injuries that began less than a half-dozen seasons into his American League sojourn with the Minnesota Twins would soon cut short a potentially unparalleled career, steal away what might have been some of his prime seasons, and (for a long time) rob him of almost certain Hall of Fame status. In the end the only thing that Cuba’s Tony Oliva lacked on a baseball diamond were healthy legs and thus a measure of reasonable career longevity.

It was the original “Cuban Comet” Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso who a dozen years before Oliva’s arrival paved the way for dark-skinned Latinos on big-league diamonds. Oliva would ironically not only compile a career resume highly similar to that of his pioneering countryman but would also share with Miñoso many of the debilitating misconceptions and misunderstandings – both intentional and unintentional – that plagued the careers of a dozen or more groundbreaking Latin American imports of Fifties and Sixties-era “golden age” baseball. Both played on the big stage under falsely assigned monikers that were not their natural given or family names (a fate also shared by Felipe Alou and his two big-league brothers, as well as by Puerto Rico’s Vic Power).1 And while Tony Oliva remained outside of Cooperstown for many years by not hanging around long enough, Miñoso’s hopes were harmed by remaining on the scene just a little too long.2 Both were victims of reigning stereotypes, and both were clearly undervalued by racially insensitive writers and fans, as were so many Latinos of their pioneering generation. Both were, however, inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2022.

A decade into his own 15-season big-league sojourn Oliva would comment with astute awareness but surprisingly little apparent anger about the second-class status he shared with his countrymen as a Spanish-speaking Latino ballplayer. In his late-career autobiography (penned with the assistance of St. Paul baseball beat writer Bob Fowler while still an active player) he spoke of the lack of commercial opportunities as merely a considerable annoyance. During 1971 spring training the veteran Twins hero had filmed his first television spot (alongside Cincinnati Reds star Pete Rose) promoting Gillette razor blades.

Speaking of his personal excitement surrounding that rare opportunity, Oliva could not avoid observing that, despite his elevated status as a hometown hero, local businesses had always skipped over him for (often less prominent) White athletes to push their commercial products. He had for a long time dismissed such oversights as a simple result of his broken English, but was eventually disabused of that illusion when he began noticing French Canadian hockey stars gracing the local airwaves with just as little English fluency as his own.3

Oliva chose to relate his own plight to a broader discomfort share by all athletes of his race during that immediate post-baseball integration era: “Blacks and Latins must realize that they don’t get nearly as many chances to do commercials or make endorsements as the white players. That’s why when the Gillette people contacted me in March I was shocked; I was flattered, too, that they would think of me. But I don’t know if my commercial with Rose was good or not; I never saw it.”

The observation (as polished by co-writer Fowler) reveals Oliva’s quiet reserve as much as his underlying resentments. Unlike contemporary Latino stars Roberto Clemente and Felipe Alou, the humble and respectful Oliva never turned such dissatisfactions into a personal crusade and never sought out a visible stage with local baseball beat writers for outspoken advocacy against the abuses of Latino ballplayers. Far less outspoken than Clemente, Oliva remained far less controversial and thus often also far more easily overlooked and undervalued both on and off the diamond.

The future Minnesota Twins star grew up during the pastoral 1940s on a family farm in Cuba’s rural Pinar del Río Province, the lush tobacco-growing region that also produced star pitcher Pedro Ramos for the same Griffith-family-owned American League franchise. Born on July 20, 1938, Pedro (Pedro Oliva II, his given birth name) was the oldest of four boys and the third of ten children in the family of Pedro and Maria López. Of three younger brothers, named Antonio, Reynaldo and Juan Carlos, the latter two would also prove to be talented ballplayers on their native island. Of five sisters, Maria Antonio and Gricelia were the oldest of the brood, while Irene, Adelia and Felicia were all younger than the first-born son.

The elder Pedro harvested tobacco, oranges, mangos, potatoes, and corn on his one-mile square plot located outside the hamlet of Entrongue de Herradura and approximately 40 kilometers distant from the provincial capital also labeled Pinar del Río. Pedro senior also possessed local fame as an expert cigar roller and during his youth had enjoyed a successful stint as a semiprofessional ballplayer on local and regional diamonds.

Baseball ran deep in the Oliva family blood (as it did and still does in the blood of most rural Cuban families), and the oldest Oliva son learned the finer points of the game early on from his once-talented father. Pedro senior built a crude diamond on the family farm for a local squad that played area opponents on Sunday afternoons. Tony took up the sport by the time he was seven and was finally able to crack the lineup of the neighborhood ball club (which also included his father as the catcher and sometimes outfielder) for a single summer when he was fifteen. Tony would later credit his father in the pages of his autobiography for providing hours of invaluable evening practice on the family diamond, but more even specifically for long lectures about the subtle art of hitting.4

The soon-promising young athlete was inked to a professional contract by Minnesota scout Joe Cambria in February 1961, several months before his 23d birthday.5 Cambria was at the tail end of his own legendary scouting career in pre-Castro Cuba that had produced dozens upon dozens of prospects (and a handful of eventual big leaguers, including stars Pedro Ramos and Camilo Pascual) for the Griffith-family franchise in Washington. Cambria had been alerted to the hard-hitting prospect by former Washington Senators journeyman minor leaguer Roberto Fernández. Also a Pinar del Río native, Fernández had been playing alongside Oliva during the winter season on the Los Palacios village ball club that competed in a strong provincial league in western Cuba. Fernández had contacted Cambria who was then based in Havana and alerted him to a raw but promising youngster who “could hit all pitches to all fields and had a strong arm” and who thus merited immediate signing.6

It is unclear if Cambria knew Oliva’s actual age at the time of extending that first contract offer, but the experienced birddog was impressed enough with the judgments of Fernández to orchestrate Oliva’s transfer as a largely untested prospect to the Minnesota farm system. As Oliva himself recounts the events, his February signing allowed only a few short weeks before a scheduled departure for spring training in the United States. The cramped time frame created a significant problem because he lacked a passport. But since his brother Antonio (older by Oliva’s telling) did possess proper documentation, a switch was hurriedly arranged and the hopeful ballplayer was cleared to leave his homeland with obviously illegitimate paperwork. The Twins’ timely offer and the availability of his brother’s passport papers enabled an escape from Cuba in the immediate aftermath of the 1959 Castro-led revolution and thus at the precise time of worsening Cuba-USA relations. One fateful consequence for the future was that the youngster would become known by a brother’s name and not his own, a fate he could never shake despite later legally changing his name in U.S. courts to Pedro Oliva Jr. (actually his rightful given name in Cuba). An equally devastating consequence was the fact that worsening relations between Washington and the newly installed Castro regime soon blocked any possibilities of returning to his beloved homeland and his family homestead for decades into the future.

There has been considerable controversy surrounding Oliva’s actual birth date, with 1938, 1940 and 1941 all appearing as alternative choices in standard baseball reference works and various on-line sources. 7 The ballplayer’s own account in his autobiography attests that he was the second son, born in 1941 and preceded by older sibling Antonio. Oliva retells the familiar tale of how after his signing with Cambria his departure from Cuba necessitated the use of his brother’s Cuban papers.

“The problem was that I didn’t have a birth certificate and couldn’t get a passport without one. It would take time to get a birth certificate. My older brother, Antonio, had one but I don’t remember why. People get them for passports, to get married, for a lot of reasons, and he had one so I borrowed it. That seemed like the thing to do; he didn’t need it, and I did. We were born on the same day, July 20, but he was born in 1938 and I was born in 1941.”8

In short, the true Antonio Oliva had a birth certificate (not a passport), and it was this that brother Pedro borrowed; the passport was indeed issued to the ballplayer, but the papers needed to acquire it were his brother’s and not his own. All this led to “Tony” Oliva’s arrival in the United States with a false name (but not a false age, as it turns out) that then immediately became part of his lasting legacy. Oliva’s own account was later contradicted by his wife in a 2011 newspaper interview which seems to clarify the issue. Gordette Oliva explains that Tony was indeed the elder (the one born in 1938) and being already 23 when he inked with the Twins he (likely on the advice of Cambria) assumed that he might stand a better chance of making the grade if the ball club thought him younger than he actually was. This was a standard practice with Latino ballplayers in the 1950s and 1960s (and has also been known to occur in more recent decades).

One of course might think that any individual would have the final word on his own birthdate.9 But Gordette’s explanation goes far toward explaining why Tony might well manipulate the facts for an autobiography written while he was still an active player. He would not have wished in 1973 to admit publicly that he had lied to the Twins a dozen years earlier. And there is yet a stronger argument that Oliva had fudged the story about his own age and that of his brother. It is far more plausible that the oldest son in the family would have been a “junior” in accord with the popular Hispanic tradition of first-borns being their father’s namesakes. It would hardly seem logical that Pedro Oliva would have dubbed his first son Antonio and his second male child (the eventual major leaguer) Pedro; it should have been (and seemingly was) the other way around.

Complex circumstances surrounding Pedro (now renamed “Tony”) Oliva’s departure from his homeland almost cancelled out a promising career before it even got started. First off, there were visa-related delays upon his arrival in Mexico City, where Tony and a contingent of fellow Cuban-born Minnesota Twins rookie prospects (reportedly numbering more than 20) sat marooned in a hotel for 11 days awaiting the proper papers permitting their entry into Miami. Upon their eventual arrival at the Minnesota rookie camp in Fernandina Beach (Florida) a half-dozen of the darker-skinned Cubans (Oliva included) were turned away from the assigned local hotel and forced into cramped lodgings in private Negro homes. For the young and racially naïve Cuban import this was his first disturbing brush with a brand of racial prejudice still rampant in the American South of the early 1960s. But an even greater setback was the fact that a late arrival had cut short Oliva’s limited time to impress scouts, coaches, and minor-league managers working at the Minnesota rookie camp.

Appearing in four inter-squad contests in the mere five remaining days of camp tryouts Oliva collected seven hits in 10 trips to the plate. His outfield play was rough and unpolished, however, and despite the brief hitting spree he was one of a handful of island imports given a quick release and told to pack his bags for shipment back home. Tony’s own recollection of the disastrous first tryout (as reported in his autobiography) was that his chances were severely limited not only by such limited exposure but also by racial politics. Of the two remaining clubs in the lower-level Minnesota farm system with open roster slots, only Erie (located in Pennsylvania) was able to use Black-skinned ballplayers. And Erie had already grabbed one of the earlier-arriving Black Cuban hopefuls and therefore had no opening left either.

A rare break that would save Oliva’s career from an immediate dead end came when sympathetic Joe Cambria decided to intervene on behalf of Oliva and two young countrymen by contacting Phil Howser, general manager of the organization’s Class-A club in Charlotte, North Carolina. Cambria lobbied for assistance in placing the desperate hopefuls with any team that might have them. In retrospect the phone call was probably the most significant service that Cambria (signer of so many journeymen Cubans who filled the Washington rosters in the Fifties) ever provided for the Griffith family and their basement-dwelling ball club. Howser fortuitously agreed to take the Spanish-speaking trio under his wing for a few days in Charlotte while he attempted to find openings on a number of Class-D squads then operating throughout the Carolinas. After six weeks of desperate waiting in Charlotte (and only a month after the April 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion had set in motion events that would soon begin isolating stateside Cuban ballplayers from their families back on the native island), Howser was finally able to find Tony a vacant roster assignment with a short-season rookie-league ball club located in rural Wytheville, Virginia.

Oliva – already almost 23 – thus began his soon-stellar career in the Class-D Appalachian League and again encountered immediate problems of linguistic and cultural adaptation. Since Wytheville did have hotel space for Blacks, the Spanish monolingual prospect was lodged in a Negro rooming house with two Black American teammates. He walked daily to and from the ballpark, and his dining was restricted to the single eatery serving local Blacks.10 He had equally as much trouble communicating on the field as he did ordering food when away from the park. Already a weak fielder, he particularly struggled with fly balls during night games since he had never played under lights back home in Cuba. Teammate Frank Quilici (a teammate and one of his future managers with the Twins) provided a much-needed assist in aiding Tony with English lessons, and easy-going manager Red Norwood displayed considerable patience with his raw “good hit, no field” prospect. But it was another encouraging visit by Cambria that finally eased the initial pressures and convinced the increasingly depressed Cuban prospect to put up with such rough times and growing homesickness until things took a turn for the better.

The turnaround was not long in coming. Despite some pronounced defensive shortcomings in right field, Oliva simply tore up the league with his hot bat and productive offense during that debut professional season in Wytheville. Spraying the ball to all fields during a short 68-game schedule, the promising Cuban’s .410 average was that summer’s best in all of Organized Baseball. Even his fielding showed some improvement under the tutelage of Norwood, and although he committed 14 errors (second worst in the circuit among outfielders), to go with a fielding percentage of .854, his strong arm allowed him to pace the league in outfield assists. Since a return to Cuba for the winter was now out of the question because of mounting tensions between Washington politicians and the Castro government, Tony was rewarded for his strong debut showing with an invitation to spend September in Minneapolis working out with the parent big-league club. The Twins then assigned him to the wintertime instructional league in St. Petersburg, Florida for further polishing.

A fast start in 1961 (after so many initial delays) only accelerated at breakneck speed during the summer of 1962. Realizing they had a true prospect on their hands – one they had almost let get away – Twins management decided to protect Oliva in early 1962 by elevating him to the 40-man roster and thus also extending a spring training invitation with the big club. Surprisingly promoted to the top of the system with the AAA Vancouver club at the end of the spring, Tony was quickly reassigned to the Class-A Sally League where he opened his second campaign with Phil Howser’s Charlotte Hornets. Here the rapidly-developing phenom was even more impressive than he had been as a rookie league upstart, again posting big numbers on offense with an average of .350, plus 17 round trippers and 93 RBIs in 127 games. While Charlotte finished in the league basement, Tony was a league all-star selection (alongside Macon second baseman Pete Rose and Savannah third sacker Don Buford) and also tabbed as circuit MVP. His .350 BA virtually tied league-leader Elmo Plaskett (but his 469 ABs missed the cutoff for the official league crown). It was all enough to earn a brief nine-game September trial with the American League Minnesota Twins after fewer than 200 minor-league games.

After a second winter season with the Florida Instructional League club in St. Petersburg, Tony continued a torrid hitting pace during his second spring training tour with the Twins and headed north with the club when the team broke camp at the end of March 1963. The brief dream of a leap to the majors in only his third pro season quickly crashed, however, when the Twins promptly reassigned him to AAA Dallas-Ft. Worth of the Pacific Coast League on the eve of the new campaign. Fortunately, he overcame an immediate impulse to reject the demotion and return to Cuba thanks to some sage advice from veteran Twins teammates Vic Power and Zoilo Versalles. Tony himself would soon enough readily admit that the further minor-league seasoning was far more of an advantage than a career setback. A third strong campaign at the plate (this time under the guidance of future big-league manager Jack McKeon) featured a .304 average (sixth best in the league), 23 homers, and a solid 74 RBIs. The reward was another September return to Minnesota and a second fall “cup of coffee” visit to the American League (this time with seven plate appearances, all in a pinch-hitting role). Having now obviously outgrown the instructional league, Tony made his first visit to a Caribbean island circuit that December and January, starring for Arecibo in the Puerto Rican Winter League and slugging the ball at a .365 pace (losing the batting race to San Francisco Giants all-star Orlando Cepeda by a slim three-point margin).

Tony received two especially pleasant surprises upon reporting to a third spring training session in Orlando on the heels of his winter league campaign. He found his name emblazoned above his clubhouse locker stall, and that locker also contained a uniform bearing the low number “six” – both telling signs that the club and manager Sam Mele had every intention of keeping him this time around. The uniform number (the same as the one worn by Al Kaline in Detroit) held a special significance for Tony since in his first brief stay with the Twins two seasons earlier he had been immediately awed on a first visit to Tiger Stadium by Kaline’s eye-catching talent and smooth style. The impressionable rookie quickly decided that Kaline was the one player he most wanted to pattern himself after.11

If he had not been all that highly touted by the Twins organization only two springs before his permanent arrival in Minnesota in April 1964, the now-suddenly-impressive Cuban slugger was soon enjoying one of the most remarkable and productive rookie campaigns in big league annals.12 Lodged in the second slot in an impressive Twins batting order (ahead of Harmon Killebrew, Bob Allison, and Jimmie Hall) Oliva enjoyed a 2-for-5 Opening Day performance in Cleveland against veteran Indians hurler Jim “Mudcat” Grant. In the season’s second game in Washington a warning-track fly-out in the ninth prevented the rookie from hitting for the cycle in only his second big league start. By mid-May it was already apparent that Oliva was a strong Rookie of the Year candidate as he still boasted a .400-plus average and seven homers. Despite a painful late-May sliding injury and an increasing role as the target of enemy bean balls, the pace slowed only moderately and the young Twins star was honored by fellow players (who then did the voting) as the American League’s youngest All-Star Game selection. By season’s end Oliva had established a handful of new league records for a first-year player. He also had become the first rookie in big-league history ever to capture both a league batting crown plus the circuit’s top newcomer award.13

Oliva’s complete statistical line has never been matched by another big-league rookie campaign before or since. His league-best .323 BA led the AL; his league-leading 374 total bases outdistanced runner-up and league MVP B rooks Robinson by a whopping 55; he trailed only Boog Powell and Mickey Mantle in slugging percentage; he paced the league in five additional offensive categories (hits, doubles, extra base hits, runs scored, and runs created); his 217 hits were the only league total above 200. At the ballot box he was a near-unanimous Rookie of the Year selection – with one sole renegade vote cast for Baltimore pitcher Wally Bunker. It was perhaps a bit surprising that such an unprecedented display by a league newcomer left him only in fourth place when it came to the American League MVP selection. In that vote he trailed only Robinson, Mantle, and Elston Howard.

The breakout onslaught from the Twins’ hottest new prospect certainly didn’t sag any during Oliva’s second campaign. Few big-league batsmen have done a better job of avoiding the legendary sophomore slump. Tony once again reigned as junior circuit batting champion, this time outstripping Boston’s Carl Yastrzemski (only Oliva at .321, Yaz at .312 and Vic Davalillo of Cleveland at .301 topped.300). Oliva again paced the circuit in an additional major batting category – base hits (185) and ranked in the top four in five more: runs scored (second to teammate Versalles), doubles (third), total bases (third), RBIs (third), and on-base percentage (fourth). The second batting title made him the first big leaguer ever to debut with two straight hitting crowns. And while again failing to capture an MVP award (this time thanks only to teammate and fellow Cuban Zoilo Versalles – league leader in runs, triples, and total bases), Tony was nonetheless named AL Player of the Year by The Sporting News and was a serious Gold Glove candidate in right field for good measure. Perhaps as important as any of the individual plaudits, Oliva was the key factor (alongside Versalles) as the Minnesota Twins captured their first-ever American League pennant.

That autumn’s Fall Classic provided a much-anticipated matchup between vaunted Minnesota hitting (Oliva, Versalles, Killebrew, Allison, Earl Battey, and Jimmie Hall) and exceptional Los Angeles Dodgers pitching (Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, Claude Osteen, Ron Perranoski, Jim Brewer). Many anticipated a Dodgers four-game sweep, but the more likely stalemate between American League offense and National League defense held up, and the result was a dramatic tussle that went the distance with Koufax’s brilliant Game Seven three-hit shutout proving the slim difference. Despite hanging in for seven games, the Twins’ batsmen were largely stymied by the Dodger aces; the AL champs hit only .195 collectively, and Killebrew and Versalles were the only big guns offering much productivity. Oliva for his part collected only five base knocks (a .192 average); his one homer came off Drysdale during a Game Four losing effort in Los Angeles. Outside of the injuries that would eventually shorten his career, Oliva’s uncharacteristically weak offensive performance during his only shot at a World Series ring was his biggest on-field disappointment.

That autumn’s Fall Classic provided a much-anticipated matchup between vaunted Minnesota hitting (Oliva, Versalles, Killebrew, Allison, Earl Battey, and Jimmie Hall) and exceptional Los Angeles Dodgers pitching (Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, Claude Osteen, Ron Perranoski, Jim Brewer). Many anticipated a Dodgers four-game sweep, but the more likely stalemate between American League offense and National League defense held up, and the result was a dramatic tussle that went the distance with Koufax’s brilliant Game Seven three-hit shutout proving the slim difference. Despite hanging in for seven games, the Twins’ batsmen were largely stymied by the Dodger aces; the AL champs hit only .195 collectively, and Killebrew and Versalles were the only big guns offering much productivity. Oliva for his part collected only five base knocks (a .192 average); his one homer came off Drysdale during a Game Four losing effort in Los Angeles. Outside of the injuries that would eventually shorten his career, Oliva’s uncharacteristically weak offensive performance during his only shot at a World Series ring was his biggest on-field disappointment.

So many numerous personal athletic milestones during those early big-league years were also sweetened by triumph and happiness away from the diamond. Above all else the star ballplayer’s storybook courtship and later marriage to South Dakota native Gordette DuBois in January 1968 indeed seemed like something scripted in Hollywood for the silver screen. In point of fact the real-life romance between the dark-skinned Cuban athlete and Caucasian Midwest teenager bore an eerie resemblance to a popular late-Sixties Hollywood film starring Spencer Tracy, Katherine Hepburn, and Sydney Poitier. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner – an Academy-Award-winning classic that openly tackled the subject of inter-racial marriage still so controversial at the time – debuted in American theaters less than a month before Tony’s and Gordette’s wedding. The couple’s first meeting actually came early in his rookie season and was of the most unlikely sort. Gordette, who was only 17, crossed paths with the shy Spanish-speaking ballplayer while on a senior class trip to Minneapolis. She and two dozen companions were staying in the very hotel where Oliva was living during his first month as a big leaguer. An autograph request led to postal correspondence, frequent telephone conversations, and eventual dating once Gordette moved to the big city in mid-summer to begin her first semester of business school classes.

Tony and Gordette’s first date came when the shy ballplayer escorted her and her parents (who had driven their daughter down to Minneapolis to begin her planned classes) out on the town for a formal get-acquainted dinner. (The event anticipated by several years the later eerily parallel Tracy-Hepburn film.) The couple’s match was improbable not only because of their differing racial and cultural backgrounds but also because neither spoke more than a few words of the other’s language. Gordette’s decision to carry a Spanish dictionary on their outings and also frequent dates with couples (like teammate Sandy Valdespino and his wife) who spoke both Spanish and English helped warm an early friendship which soon blossomed as a full-fledged fairytale romance.

Season number three was yet another brilliant one even if Oliva’s string of batting titles would finally run out (he was runner-up to Triple Crown winner and American League MVP Frank Robinson of Baltimore). The failure to overtake Robinson down the stretch prevented the Minnesota star from becoming the first junior circuit batter to capture three straight batting crowns since the immortal Ty Cobb did it in 1917-1919. The Twins also finished in the runner-up slot, trailing the Orioles by nine full lengths. Oliva again led the club in most offensive categories (BA, hits, runs, doubles, and triples) and was again selected to the AL squad for the mid-summer All-Star Game. An odd entry in the record books came on June 9 when he was part of a single-inning five-homer outburst by the Twins against Kansas City – the first such explosion in league history. There were additional personal batting milestones including a third straight season registering the top American League hits total. Most significant perhaps was a Gold Glove at season’s end. The latter honor showed just how far Oliva had progressed toward becoming a complete ballplayer by drastically improving the once weak defensive side of his game.

One of the most poetic descriptions of Oliva’s offensive brilliance came from the pen of Christian Science Monitor columnist Phil Elderkin in a freelance piece written for the pages of Baseball Digest. Elderkin opened his hyperbolic 1974 essay devoted to Oliva’s late-career resurrection as a pioneering designated hitter with the clever trope that “Watching Tony Oliva hit a baseball is like hearing Caruso sing, Paderewski play the piano, or Heifetz draw a string across a bow.”14 According to Elderkin (extending the clever musical metaphor) “That Old Bat Magic comes through as loud and clear as if Oliva’s swing had been orchestrated.” It is admittedly a rather strained piece of hyperbolic sports writing but also probably not a bad characterization of the lefty-swinger’s artistry with a bat.

But if he possessed a near-perfect and aesthetically pleasing swing, Oliva was made all the more dangerous (and thus all the more feared by junior circuit hurlers) by his reputation as a notorious “bad ball” hitter. In this regard he mirrored his fellow Latino and National League counterpart Roberto Clemente. In his 1974 article Elderkin quoted Oliva’s observations on an unbreakable habit of hacking away at pitches outside the strike zone. “There is no such theeng as a bad peetch. If you like the peetch, you swing. Batting a lot of luck anyway. You no locky you no get base heets. I no look at strike zone much, because even if peetch is six inches inside or outside I can still heet it.”15 Despite a politically incorrect rendering of Oliva’s words that was so fashionable for the times, the general message here is clear. Oliva was confident in his abilities to make contact at the plate, and his aggressiveness in the batter’s box always paid large dividends,

Gordette and Tony were finally married in her childhood hometown of Hitchcock, South Dakota, on January 6, 1968, and the union produced a first daughter Anita a year later and then a son (Pedro Jr.) in January 1970. After more than four decades the couple remained together in the Minneapolis suburb of Bloomington. As of 2014, all three Oliva children (there was a later son Ricardo and now also four grandchildren) reside within a dozen miles of the Oliva home base in Bloomington. On the occasion of the recent dedication of a life-sized Target Field Tony Oliva statute, Gordette granted a rare interview to the Minneapolis Star-Tribune in which she revealed numerous details about the family’s post-baseball life and their annual pilgrimages back to Havana to visit Tony’s remaining family still residing in their native communist-ruled Cuba.

In the late Sixties there were several short stints of winter ball play, first with the Dominican Republic’s Aguilas (Eagles) Cibaeñas club in 1968-69, and then with the Mexican Pacific League Los Mochis team the following two winters. The original motivation for playing in Mexico had quite a bit to do with Oliva’s growing feelings of isolation from his parents and siblings back in Cuba. When Twins teammate Sandy Valdespino had first suggested joining Los Mochis (where Valdespino also played in the offseason) Tony’s first inquiry was about the possibilities of the Mexican club obtaining visas that might permit a long overdue reunion with his estranged Cuban family. While the first effort at obtaining those visas failed during Oliva’s first month-long stint with the Mexican club in December 1969, a second effort yielded more happy results in the winter of 1970-71.16 Tony’s mother and youngest sister Felicia visited for more than a month in Los Mochis, and the joyous reunion provided a first opportunity for his aging mother to meet her two grandchildren – Anita and Pedro – and also her newly-acquired American daughter-in-law Gordette.

Oliva continued his remarkable hitting barrage for a half-dozen campaigns after his sensational debut summer. He averaged 20 dingers a year and only dipped below.300 twice during that early career stretch (hitting at a .289 clip in both 1967 and 1968). He paced the American League in base hits four more times after his rookie campaign and also led the circuit in doubles on three additional occasions. But his career was a ticking time bomb sabotaged by an inherited physical deformity in his knees. Oliva eventually endured seven painful surgeries in the same number of seasons and undergo an arduous physical rehabilitation regimen on a half-dozen separate occasions. The ballplayer’s single serious and debilitating flaw was something the Twins training staff had noticed early-on. Minnesota Twins trainer George “Doc” Lentz was quoted in Oliva’s 1973 biography as having already assessed Tony’s questionable future during an initial late-season September 1962 “cup of coffee” with the parent big-league club.17

It was in the early 1970s that that Twins star suffered his first truly debilitating setback. There had already been two surgeries in 1966 and 1967 for torn ligaments, and during the winter following the Twins’ World Series appearance surgeons removed bothersome bone chips from Oliva’s right knee. But on June 29, 1971 a major career turn came when he dove for a ball off the bat of Oakland’s Joe Rudi. Trailing the A’s by 14 games and desperate to get back in the pennant race, Minnesota was facing a must-win situation during a midseason road trip clash with the division leaders. With a 5-2 Twins lead in the home ninth, Oliva went all-out to haul in the smash by Rudi into the right-field corner. The result was significant damage to the already fragile right knee. That injury kept Tony out of nearly 30 mid- and late-season games and forced eventual September surgery to remove the torn knee cartilage; it also forced him to remain on the sidelines for the Mid-Summer Classic after his eighth-straight (and final) selection to the American League All-Star squad. But it was not enough to slow a charge to a third league batting crown that made Oliva only the 14th big leaguer and sixth American Leaguer to claim three league hitting titles. His .337 average was at the time the best in Minnesota club history. To put the icing on a mixed-blessings season, he also led the league in slugging percentage and was tabbed American League Player of the Year by The Sporting News.

It was on the heels of his third batting crown and that career-threatening injury that Tony Oliva finally took the major step of becoming an official United States citizen. His wife and children were of course natural American citizens by birth, and Tony himself had now been residing in North America for 11 years since he departed his homeland to seek his fortune as a 22-year-old baseball hopeful. Two years after the citizenship ceremonies he would speak of the event with pride but also with a dose of practicality. Traveling to Mexico was decidedly easier with an American passport and citizenship papers, and another family reunion in Los Mochis was now in the works for January 1972. If Oliva was now proud to be a naturalized American, he also strongly emphasized his unshakeable Cuban identity.18

The pride in newly achieved citizenship was soon overshadowed by the joy of a long awaited reunion between the junior and senior Pedro Olivas. Tony flew to Mexico City in early January 1972 to greet his father and sister Felicia, who were arriving for an extended stay. Oliva’s father would eventually come north for several months after the winter league season ended in Los Mochis; Pedro Sr. experienced a snowy winter in Minneapolis with Tony’s clan, and also make a lengthy automobile road trip with his son to Orlando for spring training. It was indeed one of the happiest times of the young ballplayer’s life, and Tony’s autobiography highlights those brief visits with his long-separated father. A truly special moment came for Tony when he cracked a homer in front of his father during a spring training contest, although as later related the event did not have quite the expected outcome the proud son had hoped for. Slowed by his knee surgery of the previous fall, Tony made few exhibition game appearances that spring. But he was able to take advantage of one rare opportunity and blast a fifth-inning homer against Chicago. The elated son was nevertheless dismayed when he rounded third base, glanced into the stands, and saw his father sitting placidly amidst other cheering fans. When Harmon Killebrew smashed another homer a few pitches later, the elder Oliva rose to his feet with loud applause. When a puzzled Tony asked his father about cheering more for Killebrew than for his own son, the baseball-wise elder merely responded that Killebrew’s homer was far more important because it came with a runner aboard and not with the bases empty like Tony’s.

The 1972 season turned out to be a complete loss due to the previous summer’s injury. The defending batting champion was hobbled during spring training by pain and severe swelling in the recently repaired knee that simply didn’t seem to be heeling properly. An April players’ strike delayed the season briefly and allowed a couple extra weeks of fruitless rehab at the Twins minor-league camp in Melbourne. When Oliva eventually rejoined the parent club he remained on the disabled list until mid-June. When he finally cracked the starting lineup for the first time in Cleveland, he found himself in a strange environment – left field, a position he had almost never played before. Manager Bill Rigney wanted Oliva’s bat back in lineup and opted for the new outfield slot since he thought it would demand less running from his crippled slugger. But the experiment proved fruitless, and after ten games (and despite a .321 batting mark in his mere 30 plate appearances) Oliva was back on the DL and scheduled for still another midseason surgery. During a second major operation on July 5th, doctors removed 100 cartilaginous fragments from the knee in an effort to save Oliva’s now severely threatened career.

On the heels of his frustrating lost campaign Tony journeyed to Caracas, Venezuela, to watch his younger brother Juan Carlos star for the Cuban national team during a September international junior-level baseball tournament. Juan Carlos had been only 6 at the time of his older brother’s departure for the United States a decade earlier and now was a top 17-year-old right-handed pitching prospect who eventually logged 11 stellar Cuban League seasons. Tony reports in the final pages of his autobiography that his brother had pitched his league team to the Cuban amateur league championship in 1971 and was now pitching on a Cuban national team that would win the 1972 Pan American Games tournament with a perfect 12-0 mark. None of these claims are entirely accurate since the Pan American Games (played in odd-numbered years) had been held in Cali, Colombia, during July of 1971 (where Cuba did win with an 8-0 record), and Juan Carlos did not make his rookie debut in the top Cuban League until the 1972-73 winter season (and then with a Pinar del Río team that was a basement-dwelling club during that era).19

Oliva’s own late career was partially saved – at least temporarily – when the American League introduced its controversial designated hitter rule for the 1973 campaign. Few players ever benefited more substantially or more immediately from a rule change. In the new role Oliva quickly earned a rare spot in the annals of baseball trivia by stroking the first-ever homer by a DH; the historic smash came off Oakland’s Catfish Hunter in the first inning of the April 7th season opener. Earlier the same afternoon New York’s Ron Blomberg had entered the record books as the actual first-ever DH to step into an American League batter’s box. The Opening Day smash was Oliva’s first since late in the 1971 campaign and the first of 16 he would slug that summer in his newly assigned role. On July 3 in Kansas City, Oliva also tied a club record by smacking a career-high three round trippers and matching another career best with 12 total bases. By season’s end he also paced the Twins with 92 RBIs for what was by any measure a remarkable (if rule-aided) comeback season.

Oliva hung on for three more campaigns before his bad knees finally forced him to retire during the mid-Seventies. In 1974 he logged 127 game appearances, enjoyed four four-hit games, earned American League Player of the Week honors in early July, and managed to lead the majors in pinch-hitting (7 for 13 for a .538 average). When he smacked career home run number 200 off Stan Bahnsen in Chicago’s Comiskey Park on June 27, he became only the 89th big leaguer to reach that milestone. A year later he tied Don Baylor for the major-league lead in the hit-by-pitch category (13) and upped his career pinch-hitting mark above .400. A final highlight of that penultimate 1975 season was his 27th career four-hit-plus game on July 10 in New York. But season’s end also brought with it two additional October knee surgeries (his sixth and seventh) for the removal of painful bone spurs.

Tony Oliva’s swan song campaign in 1976 included a dual role as player-coach and was limited to a mere 67 games of mostly late-inning pinch-hitting duty. There was one final four-hit outing in late July against Detroit and a final homer to nudge his career total to 220. The winter months included a stint managing the Los Mochis “Cañeros” ball club to a second-place finish in the Mexican Pacific League (his club finished the regular campaign in third place with 35-31 ledger but reached the postseason finals before dropping four of the five title games to Mazatlan).

After his playing days ended, Oliva extended his lengthy and loyal service to a Minnesota franchise that had provided his only big-league home; there were various and repeated stints as a first-base coach (1977-1978 and 1985), big-league hitting coach (1977-1978 and again in 1986-1991), and roving minor-league hitting instructor (1979-1984). It was while serving a second term in the role of batting instructor with the big-league club that Tony played a major role in the development of his protégé and future Hall of Fame outfielder Kirby Puckett. The latter duty may in some respects have been something of a bittersweet triumph for the Cuban slugger who remained outside the doors of baseball’s Valhalla until 2022. One can certainly argue that Chicago-born Puckett’s Cooperstown credentials (12 seasons, 207 homers, 1085 RBIs, .318 BA) are essentially equal to those of his never-enshrined mentor.20

If Cooperstown had yet to come knocking, there were a couple of rarely paralleled post-career honors for one of Minnesota’s most cherished big-league stars. The franchise officially retired Tony’s uniform number 6 on July 14, 1991, almost exactly 30 years after his first appearance as an unpromising Appalachian League rookie refugee from revolution-torn Cuba. He was only the third such honoree in club history (after Harmon Killebrew and Rod Carew) and has since been joined by four others (Kent Hrbek, Kirby Puckett, Bert Blyleven, and Tom Kelly). A prouder moment, perhaps, transpired for the 73-year-old Oliva in April 2011 when the Minnesota Twins unveiled an impressive larger-than-life-size bronze statue of their franchise great at the entrance to newly opened Target Field, the ballclub’s state-of-the-art twenty-first-century stadium.

Over the past two decades Tony Oliva has made numerous unpublicized sojourns back to the nation of his birth to visit with still-living family members in Pinar del Río Province. He has also held forth with crowds at Havana’s renowned Central Park esquina caliente (“hot corner”) on several occasions and delighted small clusters of island fans with colorful tales of his storied years in the big leagues. Oliva remains a larger-than-life hero on his home island even though he had been repeatedly overlooked for several decades by a generation of Cooperstown voters.

On December 5, 2021, it was announced that Tony Oliva had been elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.21 Both he and teammate Jim Kaat were named as part of the 2022 class of inductees.22

Last revised: January 3, 2022

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted

Bjarkman, Peter C. A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2007), Chapter 3.

Bjarkman, Peter C. Baseball with a Latin Beat: A History of the Latin American Game (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Publishers, 1994).

Reusse, Patrick, “Oliva a legend rooted in Minnesota,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, April 8, 2011 (http://www.startribune.com/sports/twins/119448294.html)

The Official Tony Oliva Web Site at http://www.tonyoliva.com/

Notes

1 In his Biography Project essays on Felipe and Matty Alou, Mark Armour has pointed out that both have been long misnamed: the brothers shared the surnames Rojas Alou, the first being the father’s surname and the second the mother’s family name. Following Latin American custom Felipe, Mateo (deceased) and Jesús were all known in their native Dominican Republic as the brothers Rojas. American sportswriters and baseball officials improperly used the mother’s name because it came last in the sequence (family names are last and not penultimate in English). Armour also correctly points out that the name ALOU in Spanish rhymes with LOW and not (as incorrectly pronounced in English) with LOU. Tany Pérez would be refashioned as Tony Perez in the USA (with his first name “Americanized” and his last name improperly stressed on the final syllable). It is an often repeated story of how Saturnino Orestes Armas Arrieta (Miñoso) was falsely assigned the last name belonging to two stepbrothers who were also ballplayers, and also how he earned the somewhat condescending (and feminizing) moniker of “Minnie” (see Bjarkman, A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006, Chapter 3 for details). And Vic Power (nee Victor Pellot Pove) also became “Power” through a complex set of linguistic errors during his minor league playing days in Drummondville, Canada (for details see Peter C. Bjarkman, Diamonds around the Globe, The Encyclopedia of International Baseball (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2005), 76-77.

2 Miñoso’s overall career was negatively impacted by a series of publicity stunts mostly orchestrated by Chicago White Sox ownership and especially Bill Veeck. He was inked to sham contracts which allowed him to make token appearances with Veeck’s Chicago club at ages 53 and 55 and thus join Nick Altrock as baseball’s only five-decade player. Then in 1993 and 2003 he made further “staged” and circus-like one-at-bat appearances with the minor league St. Paul Saints (owned by Veeck’s son Mike) to establish a claim as baseball’s only six- and then seven-decade player. Such distasteful stunts have only diminished what had originally been a near Hall-of-Fame status career and done Miñoso more harm than good with some Cooperstown old-timers committee voters. And racial prejudice may also have hurt Miñoso in subtle ways long after his playing days had ended. For years popular Go-Go Chisox second baseman Nellie Fox benefitted from a grass roots induction lobbying campaign that somehow never attached itself to such popular Latino stars as Miñoso (or Tony Oliva and Luis Tiant).

3 Tony Oliva (with Bob Fowler), Tony O! The Trials and Triumphs of Tony Oliva (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1973), 187.

4 ] “I owe much to my father because he helped me with baseball as soon as I started playing the game. It wasn’t that he pitched to me or hit a lot of grounders and fly balls. He did those things sometimes, but not often. Mostly he would talk to me and give me advice about playing the game and especially hitting.” (Oliva and Fowler, 4)

5 There are inconsistencies surrounding the date of Oliva’s signing, just as there are mysteries involving his true birthdate. The official Minnesota Twins website (the page on Oliva in the section devoted to retired numbers) provides a July 24, 1961, signing date, also crediting the signing to Joe Cambria and the original birddogging to Roberto Fernández. But since Oliva reported to spring camp with the Twins in March 1961 – already supposedly inked by Cambria in Havana – the July date cannot be correct. The only explanation here is that the July date refers to a resigning after Oliva was initially released in spring camp and then hooked on with the short-season Appalachian League club in Wytheville.

6 Oliva and Fowler, 6.

7 Most standard encyclopedias, including Total Baseball (Sixth Edition) and Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia (Total Sports Illustrated) both opt for July 20, 1940. That year is also found in Jim Thielman’s volume on the 1965 champion Twins, Cool of the Evening: The 1965 Minnesota Twins (Minneapolis: Kirk House Publishers, 2005).The 1938 date is not only used by Baseball-Reference.com but also by the Official Tony Oliva website. The latter site is not maintained by the ballplayer himself but approved by Oliva who is therefore most likely aware of its contents. Oliva’s 1973 autobiography is not the only source of the July 20, 1941, date; it also appears on the official Minnesota Twins website in the section dedicated to ball club retired numbers (http:/Minnesota.twns.mlb.com/min/history/oliva.jsp).

8 Oliva and Fowler, 7.

9 Oliva is not the only renowned Cuban ballplayer to provide false testimony regarding his date of birth. Take the case of Connie Marrero. Despite a number of competing and inaccurate birthdates in various encyclopedias and on the back sides of his several Topps ball cards, the date now agreed on for centenarian Conrado Marrero is April 25, 1911 (see the discussion in my own BioProject essay on Marrero). This is the date on the ballplayer’s Cuban passport and the one that is honored each year in Havana with official government-sponsored celebrations. But during my visit to Havana in January 2012 the 100-year-old Marrero repeated the tale that he uttered to this author on several earlier occasions – that he was actually born in August 1911 but that an error in family record keeping caused the April date. Outside of Marrero’s own now-questionable memory, there is no firm documentation for an August birthdate.

10 “Because I didn’t know English, I was afraid to take a chance and point at something on the menu. Once I saw a nice chocolate candy bar in a drug store, and I pointed at it and bought it. I took it back to my room to eat that night before I went to bed. Later I unwrapped it and took a bite – and gagged. It was a hunk of chewing tobacco.” Oliva and Fowler, 17.

11 Tony’s early desire to pattern himself after Al Kaline of course ignored the fact that they batted from different sides of the plate. Oliva remembers that it was fellow Cuban teammate Camilo Pascual that first suggested he pay attention to Kaline if he was looking for models to demonstrate the proper way to play right field. Clearly it was the defensive side of Kaline’s smooth game that first caught the raw rookie’s attention. (Oliva and Fowler, 37)

12 If the Twins organization may have been slow initially to warm up to Oliva’s potential, some outside the organization seemed to be even less impressed with his rookie prospects. The March 1964 issue of Baseball Digest carried the following capsule evaluation of Oliva (penned by Herb Simons) as part of their popular annual rookie forecast feature: “Real good arm. Fast runner. Fair hitter. Can make somebody a real good utility outfielder.” Herb Simons, “Scouting Reports of 345 Major League Rookies,” Baseball Digest, Volume 23, No. 2, March 1964, 104.

13 “Shoeless” Joe Jackson owns the highest-ever rookie batting mark of .408 for Cleveland in 1911 and yet didn’t win the league crown that year, thanks to Ty Cobb, who punished the ball at a .420 clip (during the first of his own two .400-plus seasons).

14 Phil Elderkin, “The DH Rule Saved Tony Oliva from Oblivion,” Baseball Digest, Volume 33, No. 9, September 1974, 49. The same poetic description is also quoted in David Pietrusza, et. al. Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia (Kingston, New York: Total Sports Illustrated, 2000), 846.

15 This is the same kind of unfortunate and clearly condescending interpretation of Latino ballplayer speech that was almost always attached to the utterances of Conrado Marrero and Orestes Miñoso in the 1950s, and Roberto Clemente, Felipe Alou, and Orlando Cepeda among other Hispanic stars throughout the 1960s. Elderkin’s article vividly demonstrates that the practice was still very much with us in the popular sports writing of the seventies.

16 Oliva reports in his autobiography (p.145) that the initial abortive effort was first delayed due to a late start with the complex visa paper work. It was then further complicated when he was duped by a dishonest local Los Mochis resident who promised to arrange the final details but in the end absconded with the $400 the overly trusting ballplayer had given him as a good-faith initial payment.

17 “Doc” Lentz was quoted by Oliva and co-author Fowler as follows: “I had been associated with athletic teams since 1930 and I had never seen an athlete with a body like his. From the hips up, he had a build as good as anyone, although he was skinny. From the hips down, well, his legs looked like those of a newborn colt. He had a deformity in his right leg; his leg from the knee down was bent at a forty-five degree angle. He was knock-kneed, but especially in that right knee. I remember thinking then, ‘If he makes it to the major leagues, he’ll last only as long as those knees hold out.’” Oliva and Fowler, 25, 26.

18 In his own words (as shaped by co-author Fowler) Oliva assessed his new-found dual identity: “I’m proud to be an American citizen, but I believe I’m a Cuban-American. You can’t be a citizen of two countries, but you can’t take an oath and give up what you are inside either, and inside I’m Cuban.” It is a rare Cuban-born big leaguer (including especially a majority of Cuban League “defectors” of the past two decades) who has not stressed his deep dedication to his native identity in almost identical phrasing.

19 Juan Carlos Oliva pitched for Pinar del Río in the Cuban League for 11 seasons between 1973 and 1983 and compiled an impressive career mark of 101-57 with a 2.46 career ERA. He would indeed make one appearance with the Cuban national team in the Pan American Games, but that was in 1979 in Puerto Rico where he would win his only decision. He would also pitch on the gold medal Cuban team in the Central American Games in Medellín (Colombia) in 1978 where his 3-0 mark left him undefeated in international games. Tony’s brother Reynaldo (three years old than Juan Carlos) also logged four Cuban League seasons as a sparsely used Pinar del Río outfielder (he had an anemic .175 career batting mark with no home runs). The squad Juan Carlos played for in Caracas in 1971 was a national junior team and why Tony would have billed the event as the Pan American Games in his 1973 autobiography is not at all obvious. But as has already been pointed out, there are a number of even more glaring biographical inconsistencies in the volume coauthored with Bob Fowler.

20 Cooperstown enshrinement of Puckett and the long ignoring of Oliva might well be taken as one of the best arguments for a popular notion that Latin American ballplayers still suffer from undervaluation and often blatant prejudice. Oliva and Puckett boast very similar career numbers and if Puckett’s stats are marginally higher they also came in an era of greater overall offensive production league wide. Both might have had more substantial Cooperstown credentials had Tony Oliva’s career not but cut short by bum knees and Puckett’s interrupted by the sudden appearance of glaucoma. Oliva was always viewed by press and fans as a model citizen off the field while Puckett’s revered early career positive image was unfortunately heavily blemished by several post-career scandals and an eventual court trial involving sexual harassment charges.

21 Associated Press and Tim Nelson, “Twins legends Oliva, Kaat among six elected to Baseball Hall of Fame,” MPRNews, December 5, 2021. https://www.mprnews.org/story/2021/12/05/twins-legends-oliva-kaat-among-six-elected-to-baseball-hall-of-fame .Accessed January 1, 2022.

22 Oliva talked about the honor with Daniel Gotera. See “From Cuba to Cooperstown: A Gotera family connection,” KHOU-11.com, December 8, 2021. https://www.khou.com/article/sports/tony-oliva-cuba-baseball-hall-of-fame/285-3826f898-8646-4ddd-a58d-e9c515024810. Accessed January 1, 2022.

Full Name

Pedro Oliva López

Born

July 20, 1938 at Pinar del Rio, Pinar del Rio (Cuba)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.