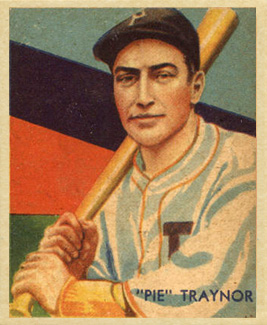

Pie Traynor

For one generation of Pittsburghers, Pie Traynor was that tanned, silver-haired old man on Studio Wrestling. For another generation, he was the monotone voice that came out of the radio every evening to talk about sports. But for an older generation — and for most baseball fans outside the Pittsburgh area — he was the greatest third baseman of their time.

For one generation of Pittsburghers, Pie Traynor was that tanned, silver-haired old man on Studio Wrestling. For another generation, he was the monotone voice that came out of the radio every evening to talk about sports. But for an older generation — and for most baseball fans outside the Pittsburgh area — he was the greatest third baseman of their time.

Harold Joseph Traynor was born on November 11, 1898, in Framingham, Massachusetts, about 22 miles west of Boston. He was the second child of 23-year-old James and 18-year-old Lydia Traynor. The Traynor family immigrated to the United States from Canada very shortly before Harold’s birth, although it is unclear exactly when. Their names appear to be absent from official immigration records and later census documents are inconsistent. The border between the Maritime region and New England was quite porous at the time so it is possible they entered the country illegally.

James and Lydia would have seven children. When Harold was 5 years old, the family relocated to Somerville, three miles northwest of downtown Boston, and soon he was nagging the older boys in his neighborhood to let him join their baseball games. When they finally gave in, they put 6-year-old Harold behind the plate — without a mask. In his first game, a pitch smacked him in the mouth and knocked out two teeth.

Undeterred by that rough initiation, Harold became a fixture at the neighborhood games, where he met the man who tagged him with his memorable nickname. Reporters told several different stories about where “Pie” came from and Traynor himself told different tales depending on the day. The truth seems to be that Traynor and the other kids in his neighborhood befriended a slightly older boy named Ben Nangle, whose family owned a popular corner store. “The kids, in fact nearly everybody in town, used to gather at [the] store in the afternoon or evening,” according to Traynor.1

Nangle sometimes would umpire the younger children’s games and then parade them back to the store. When they arrived, Nangle would ask them what they wanted. Without fail, Traynor would request a slice of pie. Nangle took to calling him “Pie Face,” which his buddies later shortened to “Pie.” Nangle later entered the clergy but he remained a baseball fan and kept in touch with Traynor for years, occasionally giving him a heads-up on a promising young player. “Only the other day I received a note from him, asking to find a job for a kid he believes is a good prospect,” said Traynor shortly after taking over as Pirates manager in 1934.2

James Traynor made a decent living working as a typesetter for the Boston Transcript, but with such a large family to feed, young Pie had to pull his weight. Starting at the age of 12, he worked after school as a messenger boy and office hand, adding a few extra dollars to the family war chest. When he wasn’t at school or work, Pie played pickup baseball games on Boston Common and for his high-school team in Somerville. In 1917 the United States entered World War I. Pie, charged up with patriotism and anxious to follow his brother Edward into the military, was turned down for enlistment. Instead, he left home for the first time and ventured to Nitro, West Virginia, where he took a job as a railroad “car checker.” His duties put him on horseback 12 hours a day checking the arrival and departure of railroad freight cars loaded with explosives. It was a somewhat dangerous job, and not just because of the dynamite. Traynor ended one shift covered in blood after being thrown from his horse, an accident that left a small but noticeable scar on his forehead. After a short time, Traynor returned home, taking a similar wartime job at the Boston Navy Yard.

After the war, Traynor managed to secure a tryout with the Boston Braves. “I wanted to play for the Braves ever since I was a little boy in Framingham,” he said. But the tryout was a disaster. He started out by taking some groundballs during batting practice. “Then the bell rang for fielding practice and I stayed in the infield,” he remembered. “I didn’t even know what the bell meant. I soon found out. [Braves manager] George Stallings ran me out of there in a hurry and I was so scared I never came back.”3 Instead, he spent the summer of 1919 playing for Falmouth in the Cape League (later known as the Cape Cod League). The next spring, though, Boston Record sportswriter Eddie Hurley arranged for Traynor to work out with the Boston Red Sox. Veteran pitcher Joe Bush watched Traynor pick groundball after groundball during batting practice. “I grabbed a fungo stick one day and yelled to him, ‘Hey, Sonny, let’s see you get the ones I’m going to hit you.’ The kid was amazing.”4 But veteran Red Sox shortstop Everett Scott, perhaps with an eye toward protecting his own job, told manager Ed Barrow that he wasn’t all that impressed. So instead of signing Traynor, Barrow recommended him to Portsmouth of the Class-B Virginia League, a team with which the Red Sox had an unofficial but not legally binding working relationship. Traynor signed with Portsmouth for $200 a month on May 11, 1920. According to Barrow, “I made it plain [to Portsmouth owner H.P. Dawson] he belonged to Boston, even though I hadn’t signed him to a Red Sox contract.”5

Batting leadoff and playing shortstop, Traynor batted .270 in 104 games. Although his glove work was suspect (31 errors), major-league teams took notice. So Dawson, who obviously looked at Portsmouth’s relationship with the Red Sox a little differently than Barrow did, sat back and dangled Traynor before one suitor after another. The New York Giants wanted Traynor, but refused to pay more than $7,500, an offer Dawson dismissed. Washington Senators owner Calvin Griffith, still annoyed more than a quarter-century later, claimed that Traynor should have been his. “They owed me the pick of their club in exchange for three ballplayers I sent them the summer before,” Griffith griped to Washington Post columnist Shirley Povich in 1947. “So I picked Traynor and thought he belonged to me. Then the owner weaseled out of it. He told me I’d have to give him $5,000 extra. … If we’d have had Traynor for third base and [Ossie] Bluege for shortstop we would have won four straight pennants instead of two.”6 On September 11, 1920, it was the Pittsburgh Pirates who, on the recommendation of scout Tom McNamara, finally met Dawson’s asking price, shelling out $10,000 for Traynor; up to that point it was the largest amount ever paid for a Virginia League player. Like Griffith, Barrow thought he’d been had. “I hit the ceiling. I grabbed the phone and called Dawson and called him everything I could think of.”7 He even appealed to American League President Ban Johnson, but there was nothing Johnson could do. The Red Sox had just let one of the best players of his generation slip through their fingers. “I never stopped giving Barrow the needle about his mistake,” said Bush.8

Traynor signed a contract for $2,200 in August and joined the Pirates on September 13. Two days later, in his hometown, Traynor played in his first major-league game. When shortstop Bill McKechnie hurt his leg in the seventh inning of the second game of a doubleheader against the Boston Braves, manager George Gibson summoned Traynor. He went 1-for-2 against Braves right-hander Dana Fillingim, doubling home the Pirates’ lone run in the ninth inning of a 4-1 defeat. Clearly, though, Traynor needed more seasoning. He played in 17 games with the Pirates in 1920, batting just .212. His defense was even worse; he committed 12 errors at shortstop, many on wild throws, for a ghastly fielding percentage of .860.

Traynor spent most of 1921 with the Birmingham Barons of the Class-A Southern Association, where he hit .336 and stole 47 bases. Manager Carlton Molesworth called him the best prospect he had seen in 20 years. Defensively he remained a mess, making 64 errors at shortstop. But in late August, clinging to a slim lead over the New York Giants in the standings, Pittsburgh called up the 21-year-old Traynor and thrust him right into the middle of the pennant race. The Bucs had been barely making do with rookie Clyde Barnhart at third base. Although Barnhart was a decent player who would have his moments over the years, 1921 was one of his worst seasons. Traynor almost immediately replaced Barnhart in the lineup, starting three consecutive games at third base in early September. On September 5 his throwing error in the top of the 13th inning allowed the game-winning run to score as the Pirates dropped the first game of a doubleheader to Cincinnati. Gibson benched Traynor for the second game that afternoon — and for the rest of the season. He appeared in only two more games and was an innocent bystander as the Pirates wilted down the stretch and finished four games behind the Giants. Teammate Max Carey believed Gibson gave up on Traynor way too soon: “He could play rings around Barnhart and he didn’t get into any of our critical games.”9

Gibson’s loss of confidence in Traynor was especially puzzling in light of the lavish praise he heaped upon the young man a few months later. Speaking in New York in January, the Pirates manager called Traynor the only man on his roster whom he absolutely would not trade. “This boy has ability sticking out all over him,” raved Gibson. “By that I mean that I can put him anywhere on my team except in the box or behind that bat.” 10Actually, Gibson really never did figure out what to do with him. No way was Traynor going to displace Rabbit Maranville at shortstop. He began spring training 1922 at second base, but he was unfamiliar with the position and played poorly. So after a couple of weeks Gibson moved him to third base. Early in the season, he played a little bit of third and a little bit of shortstop, with Maranville shifting over to play second. At the end of June, with the club struggling to play .500 ball, Pittsburgh replaced Gibson with McKechnie, who planted Traynor at third base for good. That’s where he would stay for the next 13 years.

For once, Traynor’s defense was not a liability. He made strides at third base as the year went along, thanks to tutoring from Maranville and McKechnie. “The hardest thing in going from shortstop to third base was learning to play that much closer to the hitter. It was important to know your hitters and station yourself correctly,” said Traynor.11 It was also around this time that he received a hitting tip from the Cardinals’ Rogers Hornsby, who suggested to Traynor that he use a heavier bat. Traynor said the switch to a 42-ounce bat meant he was no longer just a pull hitter. “I began to hit line drives to right field and right center.”12 Traynor wrapped up his rookie season hitting .282 — nothing special in a league where the average was .292. But he finished in the top 10 in both triples and stolen bases.

From 1923 until injuries started to take their toll around 1929, Traynor probably was the best defensive third baseman in baseball. He was 6 feet tall, which was large for a third baseman of his era, but very agile. He was brilliant at charging bunts and weakly hit groundballs and had a knack for moving quickly to his right and making backhanded stops. “Pie had the quickest hands, the quickest arm of any third baseman,” said former teammate Charlie Grimm. “And from any angle he threw strikes.”13 The Cubs’ Billy Herman agreed. “Most marvelous pair of hands you’d ever want to see.”14 To columnist Red Smith, watching Traynor play third was “like looking over daVinci’s shoulder.”15 Traynor led National League third basemen in assists three times, putouts seven times, and double plays four times. His biggest defensive flaw was his arm — extremely strong, but often wild; but he learned how to compensate, according to Herman. “You’d hit a shot at him, a play that he could take his time on, and he’d catch it and throw it right quick, so that if his peg was wild, the first baseman had time to get off the bag, take the throw, and get back on again. It was the only way Traynor could throw; if he took his time, he was really wild.”16

Dick Bartell, who broke into the majors as a shortstop and second baseman for the Pirates from 1927 to 1930, waspishly referred to those years playing alongside Traynor as “a learning experience.” Bartell didn’t like Traynor much; he thought he was selfish and a bit of a phony. But his critique of Traynor’s defense might have some validity. He said Traynor’s quick throws on even the most routine plays caused some problems that most people wouldn’t recognize. “The first baseman had to play close enough to the bag so he’d be there when the throw arrived; as soon as Pie got the ball he’d be throwing it. That forced the first baseman to play closer to first, cutting down his range. Things like that don’t show up in the fielding stats.” Bartell also noted that Traynor’s great range sometimes caused problems for a shortstop. “A ball would be hit to me at short. As I came in to field it, Pie would cut across in front of me, trying to get it. Usually he would miss it, but as he crossed in front of me I’d lose sight of it. I was charged with plenty of errors that way. … Those were routine plays for me and most of the time he couldn’t come close to making them.” Bartell was a feisty guy, even as a young player; he went to Traynor and told him to back off. “Don’t you call me off,” Traynor supposedly snapped back. “I’ll tell you what to do. I’m going to take everything I can.” Bartell kept his mouth shut after that. “He wasn’t my idea of a great team player. But I never called him off again.”17

Traynor established himself as an offensive force in 1923, putting together what might have been his best overall season at the plate. He hit .338 with a career-high 12 home runs and 101 RBIs. His 19 triples tied teammate Max Carey for tops in the major leagues, and his 28 stolen bases were also a career best. Traynor, Carey, Honus Wagner, and future Pirates stars like Paul and Lloyd Waner, Roberto Clemente, and Matty Alou had lots of similarities as hitters. Not a lot of home run power, didn’t necessarily walk much (although Carey and Paul Waner did), but they could drive the ball into the gaps and fly around the bases. Those kinds of hitters could thrive at a place like Forbes Field, with its cavernous outfield.

Over the winter of 1923-24, Traynor began thinking more about his post-baseball life. He turned down an offer of $700 to go on a 20-game barnstorming tour (perhaps he was insulted because Hornsby reportedly received $10,000 to play on the same team) and instead enrolled at a business school in Boston to try to earn enough credits to qualify for admission to Boston University. But when his eyes began bothering him a doctor suggested that he was studying too hard; he was advised to either drop out of school or get glasses. Traynor, so fanatical about his eyes that he avoided movie theaters, ditched school, and went to work as a traveling salesman for a couple of months.

The 1924 season was a bit of a letdown. Traynor’s offensive numbers dropped off almost all the way across the board. McKechnie even benched him for a time in June. Then in the fall, he found himself in the middle of a minor controversy. Prior to the 1924 World Series, Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis banned Giants outfielder Jimmy O’Connell and coach Cozy Dolan for trying to pay off Phillies shortstop Heinie Sand to “go easy” in a late-season game. Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss piled on, accusing Dolan — and, indirectly, John McGraw — of tampering with Traynor near the end of the ’23 season. Dreyfuss believed Dolan, at the behest of McGraw, had asked Traynor to hold out for a $15,000 salary in hopes that Dreyfuss would refuse and trade his third baseman to the Giants.18 Dolan told Landis he was paying Traynor an innocent compliment, just suggesting that he deserved more money. Nothing official ever came of Dreyfuss’s allegations.19

The Giants set the pace in the National League early in 1925, but by mid-June the Pirates were charging hard. After the Pirates beat the Giants 13-11 in 10 innings on June 16 to complete a four-game sweep), Harry Cross of the New York Times wrote of the Giants, “Their temperature is far above normal, respiration is alarming, blood pressure is kiting, and they are suffering from housemaid’s knee and their appetites have gone blooey.”20 The rumors of the Giants’ death were greatly exaggerated, though; they went back and forth with the Pirates until August. But from August 26 through September 23 Pittsburgh won 22 of 30 games, including a pair of nine-game winning streaks, and took the pennant by 8½ games. Traynor was marvelous, batting .320 with 106 RBIs, and leading third basemen in fielding percentage and total chances. His 41 double plays set a National League record for third basemen that stood for 25 years; four of those double plays came in one game, which set a major-league record later tied by Johnny Vergez in 1935. Traynor was an easy choice for The Sporting News‘ all-star team and finished eighth in the Baseball Writers Association of America MVP voting. Just 25 years old, Traynor already was starting to receive acclaim as one of the all-time greats. In September, McGraw called him “one of the best third baseman I have ever seen.”21 McGraw’s right-hand man, Hugh Jennings, agreed, calling Traynor, “the best third basemen I have seen since the days of Jimmy Collins and Bill Bradley.”22

After having an abscess on his hip lanced in late September, Traynor was fully healthy for the World Series matchup against defending champion Washington. In Game One, Traynor homered off Walter Johnson and made a spectacular diving grab of a Muddy Ruel smash, but the Senators won, 4-1. Down three games to one, the Bucs rallied to force a classic Game Seven. In the rain and muck of Forbes Field, the Senators touched Vic Aldridge for four runs in the first inning. But Pittsburgh chipped away; in the seventh inning, Traynor rocketed an RBI triple deep into the fog to tie the game, 6-6. He was tagged out trying to stretch it into a home run. Then with the score tied 7-7 in the bottom of the eighth, Kiki Cuyler lashed a bases-loaded two-run double off a worn-out Johnson to give the Pirates their second World Series championship. Jennings called Traynor “the real hero of the series.”23 He batted .346 and gave a virtuoso performance in the field.

At spring training in Paso Robles, California, in 1926, Traynor was joined in camp by his brother Art, four years Pie’s junior. Art was an infielder who had bounced around the minor leagues for a few years. His chances of making Pittsburgh’s major-league roster were slim — and were reduced even further by injuries and immaturity. Early in the spring he sprained his ankle. Then just when his ankle had healed, he smacked his face off a bedpost while horsing around with a teammate. Another time he reported to a game stiff and sore after taking a long, jarring horseback ride through the woods. Just before the Pirates went east, they farmed him out to Columbia (South Carolina) of the Class-B South Atlantic League. Within a couple of years, Art’s life had taken a sad turn. He washed out of baseball, moved to Hoboken, New Jersey, and started drinking a little too much. In May 1929 he was arrested while trying to rob a jewelry store in New York City. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 7½ to 15 years in Sing Sing prison.

Almost everyone from the Pirates’ championship club returned in 1926, and they added the great Paul Waner to the outfield mix. But internal dissension ripped the team apart. Pirates vice president (and former player and manager) Fred Clarke was a major problem. Dreyfuss let Clarke sit in full uniform on the bench, where he forced his advice on McKechnie and delivered withering critiques of the men on the field. Some of the players couldn’t stand him. In August, Carey, Carson Bigbee, and Babe Adams called a meeting to try to get the players to vote to remove Clarke from the dugout. Dreyfuss got wind of the so-called player revolt, immediately released Adams and Bigbee, and sold the struggling Carey to Brooklyn. The Pirates had a two-game lead at the time, but they ended up in third place, five games behind pennant-winning St. Louis. Traynor, appointed team captain after the Carey trade, felt that the controversy drained the team. “We lost our spirit. We had no zip. We slopped around and finished third when we had the best team in the league. The players started to slump off. You never saw a great club melt away so fast.”24 Dreyfuss fired McKechnie at the end of the season and replaced him with Donie Bush.

In desperate need of rejuvenation and solitude after a frustrating year, Traynor retreated to the woods of Wisconsin to do some fishing and bird hunting. Upon returning to Boston, he found himself caught up in a whirlwind of public appearances and speaking engagements. Traynor was a gregarious, jovial man who usually enjoyed shaking hands and talking baseball. But enough was enough. “For one solid week I never went to bed before two in the morning, and never in my life did I see so much cold roast beef and potato salad.”25 So in January he left home early and fled back to Wisconsin for some more peace and quiet. Those winter treks to Wisconsin became an annual ritual; Traynor would camp there for weeks at a time, often accompanied by baseball friends like Burleigh Grimes, Dave Bancroft, and Fred Lindstrom.

The 1927 Pirates added little Lloyd Waner to the lineup. Traynor took one look at the 132-pound Waner and deemed him “too small, too thin, and too scrawny.”26 But his .355 batting average helped propel the Pirates to another National League pennant, as they edged out St. Louis and the Giants in a spirited race. Traynor batted .342, drove in 106 runs, finished seventh in the National League MVP voting, and was The Sporting News‘ all-star third baseman for the third straight season. He and Paul Waner shared a bat during the ’27 season; it was one they had salvaged in the spring from Tim Hendryx, a former major leaguer playing out the string with San Francisco of the Pacific Coast League. It lasted them the entire season and then some. “We had taped it and nailed it together as long as we could,” said Traynor. “I guess Paul and I must have made more than 600 hits with it.”27 Traynor was a proud bat scavenger. “I’d find one that suited me in the Giants’ rack, for instance, and I’d tell Bill Terry I was taking it. What could he say but, ‘Sure, go ahead, Pie.’”28 In a 1931 interview, Traynor boasted that the Pirates hadn’t needed to buy him a bat since he was a rookie.

In the World Series, Pittsburgh was merely fresh meat for the ’27 Yankees, perhaps the greatest team ever. “We had just gone through as tough a pennant race as you could image … and we were worn to a bone,” recalled Traynor. He claimed that he was down to 150 pounds (from his normal playing weight of 170), while Paul and Lloyd Waner had shriveled to 125 and 127 pounds, respectively. “We were whipped before we took the field,” Traynor remarked. Legend has it that prior to Game One the young Pirates stood in front of their dugout mesmerized as Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig sent one towering drive after another out of the park. Traynor always asserted that was bunk. “It’s just not true. We finished our batting practice and immediately went in for a clubhouse meeting.”29 There is no disputing what happened once the games began, however. The Yankees ripped through the Pirates in four straight, winning the deciding game on a wild pitch by Johnny Miljus in the bottom of the ninth. Traynor was a nonfactor in the series, going 3-for-15 with one extra-base hit, although his eighth-inning single in Game Three ended Herb Pennock’s bid for a no-hitter.

The Pirates won 85 games in 1928 but fell to fourth place. Despite hitting only three home runs, Traynor piled up a career-best 124 RBIs. He also bunted a lot, leading the National League with 42 sacrifice hits (defined, until 1953, as sacrifice bunts plus sacrifice flies). Only a handful of players have ever driven in 100 runs and led their league in sacrifice hits in the same season; Traynor is the only player to do so twice, in 1927 and ’28. He ended up sixth in the baseball writers’ MVP voting in 1928. Traynor finished in the top 10 in the voting six times during his career, but 1928 was the closest he came to winning the award.

The next winter Pittsburgh traded shortstop Glenn Wright to Brooklyn; Bush planned to fill the hole by moving Traynor back to his original shortstop position and turning over third base to promising rookie Jim Stroner. Dreyfuss was skeptical, but Traynor was willing to give it a try. He hadn’t completely forgotten how to play the position; even after becoming a full-time third baseman in 1922, he had filled in at short for a game or two here and there over the years. Stroner, though, was slow to recover from an appendectomy, and Traynor was struggling with a mysterious back ailment (“One of the couplings in his vertebrae dropped out or something,” recalled Dick Bartell. “I’m not sure what it was; probably nobody else was sure either.”)30 So Traynor stayed at third in 1929, and the Pirates plugged in Bartell at shortstop. It worked out well for everyone except Stroner, who played in just six games, then vanished from the majors for good. Bartell batted .302, while Traynor came through with a mark of .356, striking out just seven times in 540 at-bats. Traynor had to cope with that sore back all season; he missed 23 games and his defense slipped a little, but he was still good enough to be named baseball’s best third baseman by the baseball writers and The Sporting News. After the season Dreyfuss wanted him to stick around Pittsburgh for more treatment on his back — at least one doctor wanted to put him in a body cast, while another suggested eight weeks of bed rest. But Traynor said no and instead made his annual winter sojourn to Wisconsin.

A nasty eye infection had Traynor on the sidelines for several weeks during the spring of 1930. It was so bad that he could hardly see out of his left eye. Thinking that the infection stemmed from another infection in his teeth, doctors resorted to pulling two teeth in hopes of clearing the bacteria from his system; even after his vision returned to full strength, Traynor still had to wear smoked glasses to protect his eye from the sunlight. He didn’t return to the lineup full time until late May, but he compiled the highest batting average (.366) and on-base percentage (.423) of his career. His most memorable day came in Philadelphia on July 23, when he hit a ninth-inning home run to win the first game of a doubleheader and then, for an encore, walloped a three-run homer in the 13th inning to win the nightcap.

As he entered his 30s, Traynor had come to assume that he would be a lifelong bachelor. Even though he was usually glib and personable, he was kind of a klutz around women; a writer for The Sporting News described him as “girl shy.”31 But during the summer of 1930, the 31-year-old Traynor announced his engagement to a tall, slender 25-year-old named Eve Helmer, who worked as a telephone operator at the Hotel Havlin, where the Pirates stayed on their trips to Cincinnati. Traynor had a couple of things working in his favor. First, unlike at many hotels, the switchboard at the Havlin was located in the lobby area, so it was easy for him to casually sidle over toward Eve and pass the time of day. Second, Eve was a baseball fan even before meeting Pie, so they had something to talk about. They married on January 3, 1931, honeymooned in California, and then moved on to Paso Robles for the start of spring training.

The Pirates struggled to a fifth-place finish in 1931 and Traynor was a big reason why. His defense was well below its usual standard, due in large part to a sore throwing arm that he nursed all season. It was a bit of an ordeal at the plate for him, too; for the first time in seven seasons, Traynor fell short of the .300 mark, at .298. Nonetheless, he drove in over 100 runs (103, to be precise) for the fifth straight year; among third baseman, only Traynor and the Atlanta Braves’ Chipper Jones would be able to make that claim. The offseason was a challenging one for the organization, full of changes. The Pirates fired manager Jewel Ens and although Traynor was reported to be one of the front-runners for the job, the Bucs surprised most observers by rehiring George Gibson. They sold veteran infielder George Grantham and brought in 20-year-old Arky Vaughan to play shortstop. Then in February, Dreyfuss died of complications following surgery. Traynor spend much of the winter in Los Angeles, reporting to Wrigley Field regularly to let Angels’ trainer Frankie Jacobs work his arm back into shape.

Traynor and the Pirates both enjoyed nice recoveries in 1932. Although a sore shoulder in late May snapped his streak of 317 consecutive games played, Traynor boosted his average back up to .329, tightened up his defense a bit, and finished third (behind Chuck Klein and Lefty O’Doul) in the balloting for The Sporting News‘ National League MVP. Against the Boston Braves on August 30, he recorded his 2,000th career hit. The Pirates entered August leading the National League by 5½ games, but a 10-20 record that month doomed them to second place, four games behind Chicago. The Cincinnati Reds wanted Traynor as their player-manager for 1933, but Traynor said he wasn’t interested — and even if he were, Pirates management wasn’t about to let him go. In ’33, the Pirates again came home in second place, this time five games behind the Giants. Traynor hit .304 and was named to his seventh and final Sporting News all-star team. On July 6 he appeared as a pinch-hitter in the inaugural major-league All-Star Game at Comiskey Park, doubling off Lefty Grove in the seventh inning.

The Pirates started strong in 1934. On May 24 they moved into first place, thanks in part to a reinvigorated Traynor, who was batting .469 (Traynor had played in only 13 games by this point thanks to a shoulder that sometimes hurt so much that he could hardly sleep). By June, though, the Pirates were in a tailspin and the fans, frustrated by the near misses of ’32 and ’33, had turned on Gibson. At a June 17 game, which the Pirates lost, 9-3, a crowd of 16,000 booed Gibson lustily every time he stuck his head out of the dugout. Two days later, with the Pirates 27-24 but losers of seven of their last eight games, Pirates president Bill Benswanger released Gibson and asked a stunned Traynor to take over as player-manager. (Officially, the Pirates said Gibson had resigned, but he admitted to friends that he had been fired.) The transition of power was unusually amicable. Traynor, Gibson, and Benswanger emerged from their meeting and addressed the team together. Gibson shook Traynor’s hand and asked permission to stop by and hang around the clubhouse from time to time, which Traynor said was fine. “I accept [the job] gladly … when I realize there is no hard feeling between me and George Gibson, for whom I have always had great respect,” said Traynor.32 He named first baseman Gus Suhr the new captain, spent 30 minutes posing for photographers in the dugout, then went 2-for-5 as the Pirates lost their first game for their new skipper, 5-3 to the Giants, and tumbled into fifth place.

Traynor promised a more aggressive style of baseball: “We have a fast team and we must take advantage of our speed if we’re going to get anywhere.” The Sporting News, however, noted an even more pressing need: “Something must be done about that Buc pitching staff pronto.”33 Traynor didn’t disagree. “We’re going to spend our time hunting for a couple of fellows who can throw that ball past hitters with plenty of smoke on it.”34

Pittsburgh fans were excited about their new manager. “The man with the smile always wins,” declared one man, “and that’s Pie Traynor for you all over.”35 Traynor’s wife, Eve, wasn’t quite so sanguine. “I’ll worry more than ever now, because Pie is a worrier. He worried so much as a player, think what he’ll do as a manager.”36 Traynor did give the team a short-term boost. Inserting veteran Waite Hoyt into the rotation proved to be a wise move. He also pulled aside the notoriously free-swinging Lloyd Waner and asked him to be more selective at the plate; Waner took the advice to heart and walked 12 times over his next 18 games. The Bucs won 10 of their first 16 games under Traynor; however, much of that record was built up against second-division punching bags Cincinnati and Philadelphia. During one of those games in Philadelphia he suffered an injury from which he would never fully recover. Traynor overslid the plate on a close play at home, and as he reached back to touch it, catcher Jimmie Wilson fell on his arm. “I felt something snap and was certain I had a broken arm,” said Traynor. “I didn’t, but I couldn’t throw well anymore.”37

Just when it appeared Pittsburgh was crawling back into the race, the Pirates lost nine straight in July and free-fell out of contention, eventually finishing in fifth place. Traynor ended the year with a .309 batting average, down from .320 when he assumed managerial duties. He appeared in his last All-Star Game that summer, playing all nine innings and carving out a place in the record books. His steal of home in the fifth inning (part of a double steal with Mel Ott) remains the only steal of home in All-Star Game history.

Through it all, Traynor appeared to be teetering on the edge of nervous breakdown. As it turned out, Eve really knew her man. Traynor was, in many ways, psychologically unsuited for the role of major-league manager. By August he had lost 10 pounds in two months, appeared remarkably gaunt, and had all but stopped sleeping. “I can’t help it,” said a desperate Traynor. “I go to bed at night and can’t get to sleep. Often, I awaken more tired than when I crawled between the sheets. I’m of a nervous temperament at all times and piloting a team which isn’t going anywhere has taken its toll.”38 When the season was over he admitted, “I often wished I was just a player again with no other worries.”39

Another of Traynor’s shortcomings as a manager was that he was just too nice a guy; players walked all over him. According to Al Abrams of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “Pie’s tactics would have gone over great with a high school or college athlete where he would have been looked up to as a hero and leader, but with a gang of thoroughly hardened, grown-up men, driving leadership is sometimes required.”40 Traynor’s teams were notorious carousers and troublemakers. They also earned a reputation, fair or not, for underachieving. “His players didn’t respect him,” said Bartell. “When one got into a brawl and wound up in the police station, Pie would bail him out and keep it quiet. No fines. No suspensions. No leadership.”41 Traynor defended himself against charges that he didn’t yell at his players enough. “I won’t do it and ruin some of my men. I tell them when they’re wrong but I’m not going to browbeat them.”42

Traynor hired former Pirates manager Jewel Ens as a coach for the 1935 season. Ens would prove to be an invaluable sounding board for Traynor. On the road they would rehash every game as they walked together from the ballpark back to the hotel. Traynor played in 57 games in 1935, but the Pirates likely would have been better off if he hadn’t. He batted around .230 for much of the year. A late surge got him up to .279, but that was still the lowest mark of his career for a full season. Worse, his arm was completely gone. He made 18 errors in just 49 games at third base. By July the pitching staff had imploded, the fans were booing, and Traynor’s weight was plummeting. The Bucs got hot in late August, winning 10 straight and moving to within six games of first; but ultimately, they finished in fourth place, in line with most preseason predictions, at 86-67.

Over the winter Traynor made a regrettable trade, sending rookie right-hander Claude Passeau, catcher Earl Grace, and $25,000 to the Phillies for 33-year-old catcher Al Todd. Traynor spent every offseason as a manager looking for a staff ace; he had one in Passeau (who won 162 games in a 13-year major-league career), didn’t recognize it, and never found anyone else as good. Reporters constantly got Pirate fans in a tizzy with rumors of one big-name pitcher or another coming to Pittsburgh, but it never worked out. In November 1934 Traynor blundered when he turned down the Giants’ offer of All-Star left-hander Carl Hubbell for pitcher Larry French and outfielder Fred Lindstrom. Hubbell went on to win 71 games for New York over the next three seasons. Two years later the Bucs made a play for brilliant right-hander Dizzy Dean, but the Cardinals’ demand of Arky Vaughan, six other players, and $175,000 proved too much. Traynor’s bids for other star pitchers like Paul Derringer, Van Lingle Mungo, and Hal Schumacher also fell short. Nor were the Pirates able to develop any great young arms in-house. Traynor was good at squeezing an extra year or two out of retreads like Hoyt, Red Lucas, and Jim Weaver; but he never found a long-term solution to his mound problems. In 1937, New York Times columnist John Kieran noted that the Pirates needed to find more pitching to contend but remarked that Traynor had “a better chance of finding 12 oil wells in his cellar.”43

Traynor’s playing days quietly melted away. He spent the 1935-36 offseason working with doctors in Cincinnati and California trying to get his arm in shape. He came to spring training with plans to play if he had to, but Cookie Lavagetto and perennial prospect Bill Brubaker showed enough promise at third base that Traynor decided not to take the field at all in 1936, although he kept himself on the active roster. In July 1937 injuries forced Traynor back into the lineup for a series against the Dodgers. He hadn’t taken infield or batting practice in weeks and admitted before his first game back, “I’m nervous as a bride. I’m really a little scared.”44 Batting eighth, he went 2-for-12 in the series and made a couple of nice defensive plays in the finale, but he hurt his finger fielding a line drive late in that game and was back on the bench the next day. On August 14 he entered a game in St. Louis as a pinch-runner, scored the game-winning run on a Paul Waner single, and that was it. The Pirates didn’t need him to play anymore that season, and as he prepared to sign his contract for 1938, he specified that it was to be a managerial contract only. With no fanfare, Traynor the player was done. His career totals over 17 seasons included 2,416 hits, a batting average of .320, and 1,863 games played at third base, a major-league record that would stand until 1960. At the time, his 1,273 RBIs were second only to Honus Wagner in Pirates history.

After fourth- and third-place finishes in 1936 and 1937, Traynor was feeling the pressure even more than usual. Pittsburgh fans were tired of teams that were good, but not good enough, and Traynor supposedly admitted to friends he thought he needed to win a pennant in 1938 to keep his job. The season didn’t start well. Pittsburgh’s most dependable starter, Cy Blanton, reported to spring training overweight. Russ Bauers, a talented but goofy right-hander who Traynor thought had “as much stuff as Dizzy Dean,” burned his hand while lighting a match. A few weeks later Bauers got liquored up with some teammates on a train, got into a friendly wrestling match, and hurt his knee. The Pirates, as they had the year before, got off to a fast start; they won their first seven games. By late May, though, they had slipped below .500 and a frazzled Traynor, who had been ejected from only two games in the previous 16 years, was thrown out twice in a span of four days. But the Pirates caught fire in June and July, going 40-14 over those months, including a 13-game winning streak. They entered September with a comfortable seven-game lead over the Chicago Cubs.

Chicago player-manager Gabby Hartnett returned from a broken thumb in September, and the Cubs immediately started playing their best baseball of the year. But still, seven games seemed a lot to overcome. Giants manager Bill Terry joked that the Pirates ought to quit baseball if they blew the lead. Traynor was irate when he read that, but a lot people agreed with Terry. On September 21, with the lead down to 3½ games, Shirley Povich wrote in the Washington Post that the World Series was coming to Pittsburgh “unless the Pirates suffer a complete collapse.” The next day Roscoe McGowen of the New York Times predicted that nothing short of “the greatest flop in history” would keep the Pirates from the pennant. A Chicago Tribune headline blared “Cubs Must Work Miracle.” The Pirates moved ahead with the sale of World Series tickets (they sold $1.5 million worth) and the construction of special bleachers at Forbes Field. But the Cubs didn’t care. They just kept on winning.

Traynor was showing a bold front. “We have the edge and will continue to have it as long as we’re in first place,” Traynor bragged. “You can call it confidence or spirit, we have both.”45 Privately, though, the team was a basket case. Benswanger was taking two different anti-anxiety medications. Traynor had dropped almost 20 pounds and was smoking like a fiend. With Al Todd wearing down, coach Johnny Gooch begged Traynor to activate him and let him catch instead of Todd, and some of the players agreed with him. The Pirates’ lead was down to 1½ games going into a late-September series in Wrigley Field, and even rookie pitcher Rip Sewell could see the team was in trouble. According to Sewell, “I pleaded with Pie to use me in that series, but I could understand when he told me he simply had to go with his regular starters.”46 On September 27 the Cubs won the first game of the series, 2-1, to close to within a half-game. Then the next day, with darkness approaching, Hartnett smacked a Mace Brown pitch over the wall in the bottom of the ninth to give the Cubs a 6-5 victory. The home run became known in Cubs lore as the “Homer in the Gloamin’.” Although Pittsburgh still had five games remaining, that blow by Hartnett shattered their spirit. The Cubs won the next day, 10-1 and officially clinched the pennant on October 1.

Reflecting on the pennant race 22 years later, Traynor was philosophical. “We really didn’t rate being up there. We were scrappy, but not a sound team in personnel.”47 But at the time he was devastated. “No one knows what starts such a thing like that, and after it starts there’s not a thing in the world you can do about it except just sit and suffer.”48 Traynor ran into Detroit pitcher Bobo Newsom in the offseason and told him, “I wish I had a complete-game pitcher like you last September. We wouldn’t have lost that National League pennant.”49 Traynor also blamed Todd for questionable pitch-calling down the stretch and traded his catcher to the Boston Bees over the winter. “Traynor had to put the rap on somebody and he made me the goat,” Todd fired back. “It’s a funny thing to me why he let me catch [more games] than any other catcher in the league the last two seasons if I was so lousy behind the plate.”50

In light of the supposed weakness of the 1938 Pirates’ pitchers and catchers, it is worthy to note an incident that happened before the season ever began. Over the winter, Chester Washington of the black newspaper the Pittsburgh Courier sent Traynor the following telegram:

“KNOW YOUR CLUB NEEDS PLAYERS STOP HAVE ANSWER TO YOUR PRAYERS RIGHT HERE IN PITTSBURGH STOP JOSH GIBSON CATCHER FIRST BASE B. LEONARD AND RAY BROWN PITCHER OF HOMESTEAD GRAYS AND S. PAIGE PITCHER COOL PAPA BELL OF PITTSBURGH CRAWFORDS ALL AVAILABLE AT REASONABLE FIGURES STOP WOULD MAKE PIRATES FORMIDABLE PENNANT CONTENDERS STOP WHAT IS YOUR ATTITUDE? STOP WIRE ANSWER”

Traynor never responded, which earned him a rebuke from noted Negro League historian John Holway. In fairness, the decision to integrate the major leagues is not one Traynor could have made independently. The next summer he told the Pittsburgh Courier, “It is a known fact that there are plenty of Negroes capable of playing in the big leagues” and that he would sign them if only he could.51 Not quite a decade later, when Traynor was working as a sportscaster, he used his radio pulpit to urge the Pirates to follow the lead of the Brooklyn Dodgers and integrate their organization by signing a pair of local black players, Maurice Peatros and Joe Atkins. In his later years Traynor enjoyed a good relationship with minority players like Roberto Clemente and Willie Stargell. Maybe he could have pushed harder for the Pirates to integrate in 1938; at the very least he should have afforded Washington the courtesy of a response. But by no means was he a virulent racist. Nevertheless, with Josh Gibson catching instead of Al Todd and with Satchel Paige in the rotation instead of, say, Cy Blanton or Jim Tobin, the 1938 pennant race could have turned out much differently.

Benswanger stood by his manager after the Pirates’ implosion, saying “We … do not blame him in the slightest for the loss of the pennant.”52 Reportedly, the Pirates even raised Traynor’s salary from $16,500 to $18,000. In spring training, Traynor tried to set a new tone for his club, releasing veteran pitcher Ed Brandt for violating curfew. “I’m sick and tired of these playboys and I’m going to have discipline if I have to run one or two more players off the squad,” Traynor vowed.53 But he couldn’t wipe the slate clean; after the 1938 collapse he seemed to have lost confidence in his team and perhaps himself: “Even if we’re out in front by ten games next September 1, we’ll keep looking back over our shoulders.”54 First baseman Elbie Fletcher, who came over from the Bees in June, observed, “That’s all they talked about on that Pirate club that year: Hartnett’s home run. I knew they weren’t going to win it. That home run was still on everybody’s mind, haunting them like a ghost.”55 The Bucs hung around the periphery of the pennant race for a while, but a 12-game losing streak in August doomed the Pirates to their worst finish in 22 years.

By late September Traynor was a dead man walking. As Bob Considine of the Washington Post so delicately put it, “Even the dear lady fans, who possess a persevering kind of baseball dumbness, knew that Pie was getting the old brass-knuckle sandwich.”56 On September 28, exactly one year removed from Hartnett’s crushing homer, Traynor went to Benswanger, tendered his resignation, and accepted a job within the organization as a scout. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported that Traynor, gracious to the end, knew he was done and chose to quit to make it easier on his old friend Benswanger. Traynor issued a statement assuring everyone that “a change in managers will put the club up where it belongs and give the fans of the Pittsburgh district a better brand of baseball.”57 Privately, he was miserable. “Some fellows can say, ‘Oh, what the heck.’ But for me, something died down here (pointing to his heart). I’m like a kid. It really hurt.”58

Traynor probably didn’t relish the thought of being out of uniform for the first time in 20 years. He met with Leo Durocher about a job on the Brooklyn Dodgers coaching staff. Durocher offered him the position, but Traynor turned it down. Over the next couple of years his name was mentioned in conjunction with minor-league managerial openings in Seattle, Buffalo, and Albany, but ultimately, he remained with the Pirates. He mostly was responsible for scouting within a 100-mile radius of Pittsburgh, but he spent a good deal of time at his home near Cincinnati. After a couple of years of scouting, he seemed restless to move on. In October 1942, with the United States engaged in World War II, Traynor tried to enlist in the Army but he was rejected because of his age. Then in 1943, he and the Pirates parted ways. According to Pirates vice president Sam Watters, “[In December] he told us he had a couple of offers. We told him to go ahead and take one of them if he wished.”59 Millions of young men were overseas, and minor-league teams were folding; there just weren’t enough players to fill the rosters. With fewer minor leaguers, teams needed fewer scouts, so the Pirates weren’t unhappy to see Traynor go. In November 1943, he took a job in Cincinnati at the United States Playing Card Company, whose plant had been converted to the production of airplane parts. He vowed to return to baseball after the war.

For Traynor, World War II was a time of transition. Soon, he would come back to Pittsburgh and embark on his second career — broadcasting. In 1944 one of Traynor’s old friends, former Pittsburgh sportswriter Jimmy Murray, took over as manager of KQV Radio and contacted Traynor about an opening for a sports director. Traynor came to Pittsburgh, auditioned, and reached a handshake agreement. In January 1945 KQV announced that Traynor would begin broadcasting six days a week on KQV. He had a 15-minute sports broadcast every weeknight at 6:30 and a 30-minute show on Saturday morning in the spring and summer called The Pie Traynor Club, during which he talked baseball with local kids. The job came at an opportune moment; Traynor needed the money. His salary had always been modest by major-league standards, he had absorbed a big hit during the stock market collapse, and the sporting-goods store he owned with Honus Wagner had gone under in just two years. Pittsburgh embraced Traynor again. About 100 people — including two judges, a state senator, Pittsburgh Steelers owner Art Rooney, and some of his friends from baseball — welcomed him home with a raucous celebratory dinner that lasted into the wee hours of the morning. He made his on-air debut the following evening, and remained at KQV for the next 21 years.

Pittsburghers loved to listen to Traynor, and his ratings usually were very good. But he was never a smooth, golden voice. Frankly, his style was a little rough. His spoke in a monotone and never used a script, contending, “I think the fans like it better when you speak straight from the heart.”60 That would have been fine, except he admitted that he always got nervous when it was time to go on the air, which sometimes made for some awkward-sounding radio. One day Traynor was interviewing a boxer who was absolutely petrified; Traynor’s first question was met with absolute silence. So was the second. And the third. But Traynor kept plowing forward, bombarding the poor guy with one question after another. “We got calls from people thinking something had gone wrong with their radio because they could only hear one side of the conversation,” said former KQV news director Alan Boal.61 In 1964 KQV’s new program director, John Rook, arrived in Pittsburgh from Denver. As he drove into the city for the first time he tuned to his new station, which spent most of the day playing hit records; he couldn’t believe what was coming out of his radio. “I strained to hear the voice of a hesitant old man announcing the day’s sporting news. A pause that seemed like an eternity was broken only by the shuffle of his script, as he began to voice a commercial for a local steakhouse,” wrote Rook. “Clearly, the announcer didn’t do much for the tempo of the station. … I made a note to inquire first thing the following morning to find out who this man was and why was he on KQV.” Rook met Traynor for lunch the next day, and as they walked to the restaurant he learned why the station had kept this “hesitant old man” on the air for so long. “Folks along the way offered their greeting to Pie; even the corner traffic cop tipped his hat as he stopped traffic for us during the noontime rush.”62

Actually, anyone who lived in Pittsburgh during the 1950s or 1960s probably saw Traynor walking at one time or another. He never learned how to drive. “I was afraid I’d find an excuse not to walk, which I always found so enjoyable, so relaxing and healthful.”63 He lived about five miles from the KQV studios and, for a while, sometimes took public transportation to work. But during a transit strike in the mid ’50s he started walking to work and never stopped. His endurance was legendary and sometimes pushed the limits of sanity. Once when he was in New York City to file reports from the World Series, he walked 127 blocks from his hotel on 34th Street to Yankee Stadium on 161st. It took him 3½ hours. “Sure, I was tired when I got there, but I was loosened up and relaxed.”64 Even as a player and manager he occasionally hoofed it from Ebbets Field in Brooklyn to the Alamac Hotel in uptown Manhattan. St. Louis sportswriter Bob Broeg suspected Traynor was “part mountain goat.”65 A chance encounter on the sidewalk with Pie Traynor was part of life in Pittsburgh. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette‘s Roy McHugh strolled alongside one day as Traynor roamed the streets like a pied piper, surrounded by a kaleidoscopic gaggle of friends and fans. “Wherever he may be,” McHugh wrote, “Traynor has chain conversations, the other participants coming and going, new faces joining in the dialogue or making way for another.”66

In February 1948 Traynor received baseball’s highest honor — induction into the Hall of Fame. He received 93 of 121 votes, just over the required 75 percent, to become the first third baseman elected to the Hall by the writers. (Jimmy Collins got the nod from the Veterans Committee in 1945.) Traynor’s induction ceremony did not occur until June 13, 1949, when he and the late Herb Pennock were officially enshrined along with the Hall of Fame class of 1949 (Three-Finger Brown, Kid Nichols, and Charlie Gehringer). Traynor got the biggest ovation of the day and made a 40-word acceptance speech that was over in seconds.

During the late ’40s, Traynor was comfortably settling into the role of “Mr. Pittsburgh.” The man was everywhere. He became a sort of professional raconteur, traveling all over western Pennsylvania, often several nights a week, speaking to clubs and fraternal organizations. In 1946 he was appointed Allegheny County’s recreation supervisor for county parks, which paid him about $3,300 a year to set up baseball schools for area kids, modeled after those that Rogers Hornsby ran in Chicago. He remained in that post for about 18 months, until general manager Roy Hamey welcomed him back into the Pirates family as a scout and goodwill ambassador. Traynor’s responsibilities were light; he ran tryout camps and baseball schools and represented the team at public events. Traynor had a chance to get back into uniform at least once, when the Cincinnati Reds offered him a coaching position in 1948; but between the radio gig and his work with the Pirates, Traynor was content.

In the early ’50s, Traynor helped found the Pittsburgh Professional Baseball Association, a group dedicated to raising money for a statue of Honus Wagner, which was unveiled outside Forbes Field on April 30, 1955, seven months before Wagner’s death; it remains standing in 2015 outside PNC Park in Pittsburgh. In the spring of 1957 Traynor joined the Pirates as a special instructor at their training camp in Fort Myers, Florida. It was his first trip to spring training in nearly 20 years. Traynor’s first assignment was to work with Frank Thomas and Gene Freese on their defense at third base. That particular project wasn’t too successful; but until his death, Traynor came back to Florida for a couple of weeks every spring, putting on the uniform, riding the team bus on road trips, umpiring intrasquad games, and for many years taping interviews and reports for KQV. Unlike a lot of old-timers, Traynor refused to mire himself in the past. “The ballplayers have changed but the talent is always there,” he observed. “I guess I have a soft spot for the old timers but I respect the kids playing today.”67 They respected him, too. On June 19, 1972, Roberto Clemente passed Traynor for second place on the Pirates’ all-time RBI list but refused to acknowledge the standing ovation. “The man whose record I broke was a great ballplayer, a great fellow. And he just died here a few months ago. That’s why I didn’t even tip my cap.”68

Traynor lost his radio job in 1966. ABC, which owned KQV, preferred Howard Cosell and his syndicated sports show. According to Rook, “They argued that Pie was limited to mostly Pirate and/or baseball information; and Cosell covered the full gamut of sports, especially Muhammad Ali and football, that Pie ignored.” On top of that, Rook noted that Traynor, by then in his mid-60s, was having a tougher time getting around. “During some cold and snowy days, Pie found it difficult to make the walk from his home to the studios, and a daily 5:55 P.M. five-minute program became less than reliable.”69

But by the time of his departure from KQV, Traynor’s broadcast career had already taken a new, bizarre turn — into the world of professional wrestling. Every Saturday night, Pittsburgh television station WIIC broadcast Studio Wrestling to homes throughout western Pennsylvania. The great Bruno Sammartino was the show’s big star, with “bad guys” like Killer Kowalski and George “The Animal” Steele as his foils. Traynor announced the matches alongside local TV legend Bill Cardille. “He liked nothing more than to stop and chat with little old ladies about pro wrestling,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette sports editor Al Abrams said of Traynor.70 To baseball people who sniffed at the thought of Traynor getting involved with such a shady venture, he would wink and say, “Wrestling. That’s the only honest game left.” Traynor also turned into a popular local TV pitchman. His spots for American Heating Company were particularly memorable and unavoidable; Traynor’s tagline — “Who can? Ameri-can!” — became part of Pittsburghers’ lexicon.

In 1969 Traynor received what he once called his highest honor when he was named the third baseman on Major League Baseball’s all-time team. Two years later he threw out the first pitch of Game Three of the 1971 World Series at Three Rivers Stadium. Then on November 20 of that year, Pittsburgh sportswriters held a “Night for Pie,” which brought 16 Hall of Famers to town to pay tribute to their old friend. The writers sent Traynor a check from the profits of that evening, but Traynor sent it back, insisting, “The night alone was a whole lot more than any person could have expected.”71

By this time years of smoking were catching up with Traynor. The first sign of trouble came in 1958, when he was hospitalized with what was termed an “asthmatic condition.” Although outwardly Traynor appeared to be in wonderful physical condition, his breathing continued to deteriorate; eventually he was diagnosed with emphysema. A few days after the writers’ dinner, he was put in intensive care. Newspapers said he was suffering from a “respiratory ailment,” but that didn’t do justice to the gravity of his condition; physicians had to perform a heart massage to keep him alive. Nevertheless, Traynor headed to Bradenton, Florida, for spring training in 1972 as though everything was OK; as usual, he worked with the infielders and mingled with fans, signing autographs. A discussion he had with writer Bob Broeg gives some insight into Traynor’s perspective on his health at that time. Traynor emceed a banquet honoring living Hall of Famers. He was on top of his game that night, spicing up their affair with jokes and colorful memories. After the dinner Broeg congratulated Traynor on an admirable performance, especially given Traynor’s advanced emphysema. “I don’t have emphysema,” replied Traynor.72 Traynor returned to Pittsburgh on March 11 to be inducted into the Fraternal Order of Eagles’ Hall of Fame. Five days later he was visiting a friend when he collapsed onto a couch. His host discovered him unconscious and called police, who administered oxygen as they rushed him to Shadyside Hospital. Traynor never regained consciousness and was pronounced dead at 5:34 P.M. He was survived by his wife, Eve (who died in 1977), and three brothers. He had no children.

Down in Bradenton, the Pirates were stunned by Traynor’s death. “I just couldn’t believe it when I heard that Pie died. I just couldn’t believe it,” said Willie Stargell.73 Third baseman Richie Hebner took Traynor’s passing especially hard. “I guess Pie took a liking to me because I came from Massachusetts and so did he. I used to enjoy listening to his stories.”74 Not only did Hebner and Traynor share the same home state and the same position, but Hebner also wore Traynor’s uniform number 20. “I told Pie they should have retired his number. … The guy would have gotten a kick out of that … but he seemed to want me to wear it. Pie never wanted to make a big thing out of it.”75 (The Pirates posthumously retired Traynor’s number at the 1972 home opener). Former teammates were stunned, too. “It’s a big shock,” remarked Max Carey. “Pie Traynor was not only a great ballplayer, he was a great human being. He was a superstar before anybody knew what a superstar was.”76 “When I heard tonight that he had died it kinda made me feel like crying,” admitted Lloyd Waner.77 At the funeral, Rabbi Solomon Freehof, a friend of Traynor’s who delivered the eulogy, noted, “It was surprising that the newspaper articles printed since his death dealt mostly with the inner man and his friendliness.”78 At the conclusion of the service, Eve carefully removed three roses from a floral arrangement: “For third base. And we were married on the third.”79

Traynor’s reputation as a third baseman has taken a bit of a beating in recent years. Although people once called Traynor the best third baseman in history, Bill James ranks him just 15th. A discussion on the Baseball Think Factory website indicates there are some very knowledgeable fans who think Traynor is grossly overrated, some who don’t even consider him a worthy Hall of Famer. There are several explanations for this. For one, almost everyone who saw Traynor play is dead; there are no World Series highlight films or former teammates to remind us of how good he was. For another, although he was unquestionably a brilliant third baseman during his peak years, his career defensive stats aren’t anything special. At the end of his career his arm was dead, his reflexes had slowed, and his fielding percentage and range factor were below the league average for several years. But most importantly, third basemen ain’t what they used to be. During Traynor’s career, third base was primarily a defensive position; anything a third baseman could do at the plate usually was considered a bonus. That changed during the second half of the 20th century, when third base became a sluggers’ position. It is interesting to note that on James’s list, the only pre-1930 player listed ahead of Traynor is Frank Baker. Baker probably was better, but not by much. So for a long time those who called Traynor the greatest third baseman in history could make a very legitimate case. But not now. Traynor’s numbers pale against those of modern third basemen like Eddie Mathews, George Brett, Mike Schmidt, and Chipper Jones.

If the Beatles had released “Please Please Me” or “She Loves You” in 2015 instead of 1963, we never would have heard of them. Those songs sound terribly dated today; people don’t make music that sounds like that anymore. Times change. But that doesn’t diminish the Beatles’ legacy or the historic significance of those early recordings; in the context of their time, they were amazing. Similarly, in the context of his time, Pie Traynor was an amazing third baseman. Although history might have overrated Traynor for a while, today the pendulum seems to have swung a little too far in the other direction. No discussion of great third basemen should exclude him.

A version of this biography is included in “Nuclear Powered Baseball: Articles Inspired by The Simpsons Episode Homer At the Bat” (SABR, 2016), edited by Emily Hawks and Bill Nowlin. For more information, click here.

Sources

Alexander, Charles. John McGraw (New York, London: Viking, 1988).

Barrow, Edward Grant. My Fifty Years in Baseball (New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1951).

Bartell, Dick, and Norman Macht. Rowdy Richard (Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 1987).

baseballthinkfactory.org/files/primer/discussion/24808/teams/phi.html

Boal, Alan. Telephone interview with author, February 18, 2006.

Boston Globe

Chicago Tribune

DeValeria, Dennis and Jeanne. Honus Wagner (New York: Henry Holt & Company, 1995).

Holway, John B. Josh and Satch (Westport, Connecticut, and London: Meckler Publishing, 1991).

Honig, Donald. Baseball When the Grass was Real (New York: Coward, McCann, and Geoghegan, 1975).

James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001).

Kelley, Brent. The Negro Leagues Revisited (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2000).

Lanctot, Neil. Negro League Baseball (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004).

Los Angeles Times

Markusen, Bruce. Roberto Clemente: The Great One (Sports Publishing, LLC, 2001).

New York Times

Parker, Clifton Blue. Big and Little Poison (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003).

Pie Traynor player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Pittsburgh Press

Pittsburgh Tribune Review

Rook, John; email correspondence, April 23, 2005.

The Sporting News

United States Census, 1910 and 1920.

Washington Post

Notes

1 Pittsburgh Press, June 21, 1934.

2 Ibid.

3 New York Times, July 12, 1934.

4 The Sporting News, January 28, 1967.

5 Ed Barrow and James Kahn, My Fifty Years in Baseball (New York: Coward-McCann, 1951), 113.

6 Washington Post, March 1, 1939.

7 Barrow, 113

8 The Sporting News, January 28, 1967.

9 Greene, Lee, “At Third Base, Pie Traynor,” Sport, July 1962.

10 The Sporting News, January 5, 1922.

11 The Sporting News, August 2, 1969.

12 Bob Broeg, Super Stars of Baseball (St. Louis: Sporting News, 1971), 255.

13 Ibid.

14 Donald Honig, Baseball When the Grass was Real (New York: Berkley Publishing, 1974), 129.

15 Washington Post, August 31, 1971.

16 Clifton Blue Parker, Big and Little Poison (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 163.

17 Dick Bartell and Norman Macht, Rowdy Richard: The Story of Dick Bartell (Berkeley California: North Atlantic Books, 1993), 70.

18 Washington Post, October 3, 1924.

19 The Sporting News, October 16, 1924.

20 New York Times, June 17, 1925.

21 Los Angeles Times, September 13, 1925.

22 New York Times, October 17, 1925.

23 Ibid.

24 Bartell and Macht, 43.

25 Los Angeles Times, October 20, 1927.

26 Parker, 66.

27 Los Angeles Times, December 16, 1931.

28 Harry Keck, “Stolen Bats Sweetest: Traynor,” Baseball Digest, July 1945.

29 New York Times, October 5, 1960.

30 Bartell and Macht, 69.

31 The Sporting News, January 8, 1931.

32 Washington Post, June 20, 1934.

33 The Sporting News, June 21, 1934.

34 Pittsburgh Press, June 20, 1934.

35 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 20, 1934.

36 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 17, 1936.

37 The Sporting News, August 2, 1969.

38 The Sporting News, August 9, 1934.

39 The Sporting News, November 15, 1934.

40 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 2, 1939.

41 Bartell and Macht, 55.

42 The Sporting News, July 23, 1936.

43 New York Times, March 14, 1937.

44 Pittsburgh Press, July 21, 1937.

45 Chicago Tribune, September 28, 1938.

46 The Sporting News, November 30, 1949.

47 The Sporting News, October 5, 1960.

48 Chicago Tribune, September 20, 1938.

49 Washington Post, January 7, 1939.

50 Los Angeles Times, March 26, 1939.

51 Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 223.

52 Pittsburgh Press, October 18, 1938.

53 The Sporting News, March 20, 1939.

54 Los Angeles Times, March 9, 1939.

55 Honig, 51.

56 Washington Post, September 30, 1939.

57 Washington Post, September 29, 1939.

58 Washington Post, February 22, 1940.

59 Pie Traynor file at National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

60 Ibid.

61 Pittsburgh Tribune Review, August 8, 1999.

62 johnrook.com/johnrook.pie.htm (accessed March 20, 2015).

63 The Sporting News, August 2, 1969.

64 Ibid.

65 Pie Traynor Hall of Fame file.

66 Pittsburgh Press, November 19, 1971.

67 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 17, 1972.

68 Bruce Markusen, The Great One (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2001), 293-294.

69 John Rook, email correspondence, April 23, 2005.

70 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 18, 1972.

71 Pittsburgh Press, March 22, 1972.

72 The Sporting News, April 1, 1972.

73 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 21, 1972.

74 Ibid.

75 Ibid.

76 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 17, 1972.

77 Ibid.

78 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 21, 1972.

79 Ibid.

Full Name

Harold Joseph Traynor

Born

November 11, 1898 at Framingham, MA (USA)

Died

March 16, 1972 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.