Paul Molitor

Clad in the uniform of his hometown team, Paul Molitor stood on third base after he collected the 3,000th hit of his major-league career. The first player ever to reach the milestone with a triple, Molitor enjoyed a number of memorable moments in a Minnesota Twins uniform through the final three seasons of his 21-year Hall of Fame career. Just the 21st player ever to reach the magical mark, he was the second from St. Paul, Minnesota. Dave Winfield, who like Molitor had emerged from the sandlots of St. Paul to star for the University of Minnesota Golden Gophers, had achieved the milestone three years to the day earlier, also in the uniform of the Twins in the twilight of a Hall of Fame career.

Molitor’s path to third base that September evening in 1996 took many turns. Hamstrung by a series of devastating injuries early in his career as an infielder with the Milwaukee Brewers, Molitor developed a reputation for fragility, and it appeared that his career was cursed as seasons were cut short. But the soft-spoken right-handed hitter from St. Paul persevered to achieve milestones of durability as a designated hitter for the Toronto Blue Jays and the Twins. In 21 seasons, he collected 3,319 hits in 2,683 major-league games, belted 234 homers, scored 1,782 runs, and drove in 1,307. A seven-time American League All-Star with a smooth swing, above-average speed, and outstanding base-running skills, he finished his career with a .306 batting average and became just the fifth player in major-league baseball history to collect 3,000 hits and 500 stolen bases.

A fixture atop the Milwaukee lineup for 15 years as one of baseball’s best-ever leadoff hitters, Paul Molitor was nicknamed the “Ignitor” for the spark he generated — a nickname he never really warmed to. “Aside from its not even being spelled right,” Molitor quipped, “it’s a terrible nickname. I never once entered a room and my friends said, ‘Hey, it’s the Ignitor!’”1 Still, as the leadoff hitter in the Brewers’ batting order for a decade and a half, Molitor ignited rallies for Harvey’s Wallbangers, the 1982 team that he and close friend Robin Yount led to Milwaukee’s only American League pennant and World Series appearance. “I think he’s one of the best baserunners — not for speed but for instincts — in the game ever,” his one-time manager Tom Trebelhorn marveled.2 As to his overall impact, “In Milwaukee, It’s God, Robin Yount, and Paul Molitor,” Brewers teammate Dave Engle once observed.

Called Paulie or Mollie by friends, Molitor later replaced Winfield as the designated hitter in the middle of Toronto’s lineup in 1993. As Winfield had done in 1992, Molitor helped lead the Blue Jays to a World Series championship. Known as a clutch hitter, Molitor appeared in five postseason playoffs, including the two World Series, and batted .368. “Paulie had a way about him where if you gave him a chance, he could always beat you,” Hall of Fame manager Sparky Anderson gushed. “He’s what I call a winning player, like Joe Morgan. They’re just winners.”3 And while one needs to take this statistic with some skepticism due to all the confounding factors involved, it is interesting to note that during his career Molitor’s teams were 1382-1268 (.522) with him in the lineup and 281-349 (.446) when he was out.4

A player representative for much of his career, Molitor was at the center of several well-publicized contract negotiations. He won a battle with cocaine abuse during the injury-ravaged early part of his career, overcame the negative publicity that surrounded his mention in the trial of a prominent drug dealer, and delivered persuasive anti-substance-abuse messages to young people later in his career. Popular in both Milwaukee and Minnesota, Molitor remained close to baseball after his active career ended in 1998. After the 2014 season he was named manager of the woeful Minnesota Twins and spent four years at the helm, including one wild card appearance.

Paul Leo Molitor was born on August 22, 1956, in St. Paul, Minnesota, to Kathleen and Richard Molitor, an accountant with the Burlington Northern Railroad. Paul was the fifth of their eight children, six girls and two boys. When Molitor began playing organized baseball he lived near Grand Avenue and Pascal Street. Even as a seven-year-old, Molitor began earning recognition as a great baseball player and athlete. When he was about eight, the family moved to a large three-story Victorian home at the corner of Portland Avenue and Oxford Street. A big Minnesota Twins fan, Molitor remembered having his father toss balls high against a fence while he tried to jump up and pretend to be Twins outfielder Bob Allison robbing “a batter” of a home run. When he finally reached the majors, Molitor chose uniform number 4, Allison’s number on the Twins, although not just because it was Allison’s.5

In his new neighborhood Molitor began playing baseball at the nearby Oxford playground, celebrated for the recent play of another future Hall of Famer five years his senior, Dave Winfield. The youngster quickly took to baseball and dreamed of a major-league career — in his senior yearbook Molitor declared his ambition: “to play pro baseball and work with people.” 6Molitor’s skill quickly became apparent, and he played in several organized youth leagues, most notably for Attucks-Brooks American Legion Post 606. In the youth leagues, he occasionally competed against another future big-league star, St. Paul native Jack Morris. As a youngster, Molitor suffered a number of fluke injuries, presaging his early career in the majors. When he was about eight, he fell out of a tree; a couple of years later he injured his foot while riding his bike barefoot.7

As a teenager Molitor was given a baseball autographed by Babe Ruth. The ball made enough of an impression that when Molitor reached the majors he began collecting baseballs autographed by Hall of Famers and potential Hall of Famers as souvenirs of his time in the game. Molitor would typically get his autographs at old-timers events, and by the 1990s he was up to 40 to 45 balls.8

Molitor attended Cretin High School (now coeducational Cretin-Derham Hall), a Catholic-military prep school that is legendary for its athletics. One of the best athletes in the school’s storied history, Molitor lettered in soccer, basketball, and baseball in his sophomore, junior, and senior seasons from 1972 to 1974 and won titles in each sport. He was named all-state in both baseball and basketball.9 In baseball he played for legendary baseball coach Bill Peterson, who also coached Molitor in American Legion ball.

Molitor missed much of his senior baseball season with mononucleosis. He was just recovering in time for the state tournament and received guarded permission from the doctor to play. One of Bill Peterson’s favorite Molitor stories came from that state tournament. In the middle innings against a tough opponent, Cretin was trailing 2-1. Molitor came to the plate with the bases loaded and worked the count to 3-0. Peterson gave his star the take sign. The pitch came in over Molitor’s head, but he swung anyway. Fortunately for Molitor, he tomahawked the ball for a grand slam and escaped his coach’s wrath.10

After his senior prep season in 1974, the St. Louis Cardinals drafted Molitor in the 28th round. As a low draft pick, Molitor would have been considered a long shot to make the majors, and accordingly the Cardinals offered a signing bonus of only $4,000.11 Despite not having any college scholarship offers that strongly appealed to him, Molitor held out for $8,000 from St. Louis.12 Fortunately, as he weighed his options, University of Minnesota baseball coach Dick Siebert offered him a scholarship.13

At Minnesota it quickly became apparent that Molitor was going to be something special. As a freshman in 1975 the 6-foot Molitor weighed 170 pounds, and Siebert eventually installed him as his starting second baseman. Molitor lived up to his billing, hitting .375 and missing the All-Big-Ten first team by one vote.14 Siebert called him “the most exciting player I have ever coached.”15 Molitor recalled Siebert’s dedication to the basics: “Dick was a stickler for fundamentals, and when you practice for two months indoors during the wintertime, you get pretty good at them.”16

The next year Siebert moved Molitor to shortstop, and Molitor responded with his best collegiate season. In Big Ten play, Molitor hit .406, third in the league, and finished second in home runs and fourth in runs batted in. For his season, Molitor was named to the All-Big-Ten first team and a first team All-American, only the seventh Gopher to receive such an honor. The team finished 36-9, earning a berth in the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s (NCAA) Rocky Mountain Regional tournament. The Gophers started slowly and were later eliminated from the double-elimination tournament by top-ranked Arizona State. Later that summer, while playing in the Western Collegiate League, Molitor suffered a fractured jaw, ending his summer season.17

Molitor started his junior season slowly, which coach Siebert attributed to “pressing with so many major-league scouts following him.”18 He soon recovered and turned in a fine junior season, if slightly below his phenomenal sophomore performance. He hit .325 with six home runs and 20 stolen bases and repeated as an All-Big-Ten first-teamer. The team finished 39-12 and again qualified for the NCAA postseason. Playing in the Mideast Regional at home at Bierman Field, the Gophers won three games to qualify for the College World Series, their fifth and most recent appearance as of 2008. The team lost two of three games, the final to eventual champion Arizona State, and finished sixth.

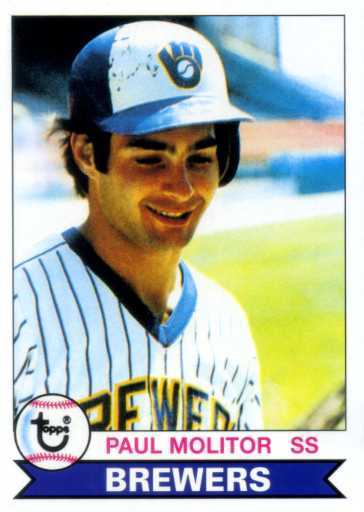

Eligible again for the draft after his junior season, Molitor was taken by the Milwaukee Brewers in the first round, third overall. Brewer scout Dee Fondy signed Molitor for an $80,000 bonus.19 At the time of his jump to professional ball, Molitor held several University of Minnesota batting records, most since broken given today’s longer season. For his play at Minnesota, the university retired his number 11. He was also awarded the university’s highest commendation, the Distinguished Service Award.20

After the draft the Brewers invited their new phenom to Milwaukee County Stadium for the VIP treatment. While wearing a suit that was “way too big, I’m totally geekish,” Molitor met some of the players in the dugout. At one point he was sitting next to shortstop Robin Yount, only 22 years old but already in his fourth year as a starter. Veteran third baseman Sal Bando stopped by and threw Yount an outfielder’s glove, telling him, “Well, I guess this will be your last year at shortstop, kid.” Molitor remembered acute embarrassment at the whole proceeding and just wanting to get away.21

Molitor was not quite ready to push Yount to the outfield. After his visit, the Brewers farmed the 20-year-old to Burlington (Iowa), their Class A team in the Midwest League. The Bees were 28-42 over the season’s first half, but with Molitor on board for the second, manager Denis Menke’s club posted a 43-26 record. In 64 games, the youngster from St. Paul stung the ball at a .346 clip, smacked eight homers, and drove in 50 runs to earn Midwest League Most Valuable Player and Prospect of the Year honors. In the playoffs the Bees buzzed Cedar Rapids (Iowa) in the first round and then met Waterloo (Iowa), the regular-season champions, in the finals. Burlington turned back Waterloo, two games to none, to capture the league championship.22

His solid half-season earned Molitor a trip to the Brewers’ spring training in Chandler, Arizona. New manager George Bamberger and general manager Harry Dalton had inherited a Milwaukee squad that finished sixth among the seven teams in the American League East Division in 1977, ahead of only the expansion Toronto Blue Jays and 33 games behind the world champion Yankees. The Brewers intended to farm the St. Paul native to Spokane in the Pacific Coast League for additional seasoning. Yount, however, was unavailable to start the season due to an injured foot and his threats to become a professional golfer. In response, Bamberger named Molitor his starting shortstop and leadoff hitter despite only a half-season of minor-league experience, in Class A at that.

The Ignitor made his major-league debut on Opening Day, Friday, April 7, 1978, at County Stadium. He grounded out in his first at-bat, then singled to left and drove in a run against Baltimore’s Mike Flanagan in the second inning in an 11-3 win. A day later, he hit his first home run, a three-run shot off Joe Kerrigan, singled twice, and drove in five runs in Milwaukee’s 16-3 win over Baltimore. On the season’s third day, he collected three more hits.

When Yount returned to reclaim the shortstop spot, Bamberger moved Molitor to second base. He continued to hit and boasted a .332 average in mid-June. Bamberger immediately took to his new second baseman. “He had tremendous instincts and you could see right away he was a talented athlete.” Bamberger said. “Not only physically but mentally, too. He played the game like he had been up here for years.”23 But Molitor batted just .183 in the season’s final month and Bamberger theorized that he was tired: “I don’t think he was used to playing that much baseball. As hard as he played, and as little pro ball as he had played, he got tired, I think. His bat slowed down.”24 Nevertheless, Molitor finished with a .273 average and 30 stolen bases to earn The Sporting News Rookie of the Year honors. While the Brewers didn’t challenge either the Yankees or the Red Sox in 1978, they did improve from 67 victories to 93 under Bamberger.

The Brewers took another step forward in 1979, when they won 95 games to finish second in the American League East behind the Baltimore Orioles. Molitor, too, improved on his previous season: he played in 140 games, hit .322 (sixth in the league), and stole 33 bases. The Brewers front office felt that in Molitor and Yount they had assembled a solid middle infield. “You say to yourself, they don’t have just physical ability, they have the right kind of attitude. They enjoy the game. They give 100 percent,” remarked general manager Harry Dalton, adding, “And you know, barring unfortunate happenings, you just look forward and say, ‘I’ve got the middle set for quite a while.’”25 After the season Molitor and his agent, Ron Simon, capitalized on that attitude and negotiated a $210,000 contract, one they liked so well that Simon needed to remind Molitor to keep a “poker face” at the negotiation.26

He started the 1980 season much the same way. But on June 6, batting .358, Molitor pulled a muscle in his rib cage and was forced out of the lineup for six weeks. Elected to the American League All-Star team for the first time, Molitor attended the game in Los Angeles though he didn’t play. To fill in while he recovered, the Brewers installed Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, native Jim Gantner, who would become one of Molitor’s close friends, at second base. While he was laid up, Molitor’s cocaine use, begun recently under peer pressure and out of frustration with his injuries, slipped out of control.27 Anxious to rejoin his teammates, he may have returned before he was ready, and his average slipped to .304 by season’s end.

Molitor’s heavy drug use continued into the offseason, and on Christmas Day 1980 reached its climax. When he failed to turn up at his parents’ home on Christmas morning, they began to worry. His fiancée, Linda, knew Molitor was at Simon’s — his agent was out of town in Florida — and went over to rouse him for the party. The door was locked, and she received no response to her banging on the door. It turned out that Molitor had hosted a wild cocaine-heavy party the night before and was still passed out. After this sorry episode Linda threatened to leave Molitor, and Molitor himself recognized the depths to which he had fallen. Molitor had been raised Catholic and attended Catholic school, but “kind of got away from it.” At the University of Minnesota he had “[undergone] a religious transformation” in the words of reporter Tim Wendel and became a devout Christian. Molitor resolved to quit the drug and credited his success to his faith. “I believe that God answered my prayers,” Molitor maintained, “and gave me the strength to fight the addiction and finally to stop using cocaine.”28

The 1981 season was one of the most frustrating of Molitor’s career. New manager Bob “Buck” Rodgers, who had split time at the Brewers helm with Bamberger in 1980 due to the latter’s heart condition, was now officially in charge after Bamberger’s retirement. Molitor had grown close to his first manager, and Bamberger’s exit saddened him. Over the 1980-81 offseason Dalton and Rodgers decided to keep Gantner at second and move Molitor to center field. This shift forced veteran star center fielder Gorman Thomas to right field, a move resented by the big slugger. To help Molitor adjust to his new position, the Brewers brought in millionaire businessman and outfield guru Sam Suplizio to help with his fielding. (Suplizio had been an outfielder in the Yankee system in the mid-1950s before a broken arm prematurely ended his career. After baseball Suplizio went on to a successful career in banking and business and became a key player in the Colorado Republican Party. Suplizio never lost his love of baseball and stayed close to his friend Harry Dalton, often helping him with scouting or as a minor-league instructor.)

Suplizio took outfield defense very seriously and traveled with a series of manuals on outfield play. The Brewers hoped that with an intense private tutorial, in three weeks or so, Suplizio could make Molitor into a competent major-league outfielder. “Paul has the potential to be great,” his tutor remarked. “It will take hard work all spring. He will make mistakes. I hope he doesn’t get discouraged when he does make them. Knowing Paul, I’m not worried about that.” Suplizio added a forecast: “He should start feeling confident about a third or fourth of the way into the season. That position isn’t a snap to learn, but there’s no doubt he’ll do it and do it very well.”29

As the 1981 season opened Molitor struggled in the outfield but seemed to be catching on quickly. Manager Rodgers, emotionally vested in the decision, probably overstated a bit when he later remarked of Molitor, “He was already better than the average center fielder. He was as good overall as [Chicago’s] Chet Lemon.”30 At the plate, Molitor hit the first grand slam of his career on April 22, but his season was cut short on May 3 in Anaheim when he suffered an ankle injury trying to beat out a grounder. While he was injured the major-league baseball players went on strike; when they returned, it was decided to split the season into two halves. Molitor returned to the Brewers’ lineup on August 12 and produced just adequately over the remainder of the season.

For the last four games of the season Rodgers adjusted his positional experiment and moved Molitor to right and Thomas — who had played center field during Molitor’s absence — back to his natural position. The team edged the Tigers to win the East Division second-half race and the right to meet the first-half champion New York Yankees in the divisional playoff series. Molitor collected five hits in the series against the Bronx Bombers and hit a home run to win Game Three, but New York won the series three games to two. Molitor’s overall performance for the season was the worst of his career for any year in which he collected substantial playing time.

Rodgers decided to move Molitor again in 1982, this time to third base, and Molitor was getting frustrated. “Last year they told me I was the center fielder of the future. Now I’m the third baseman of the future,” he deadpanned. “If [closer] Rollie Fingers retires in a few years, I might be the relief pitcher of the future.”31 To ease his concerns, Molitor received some comfort from Brewers owner Bud Selig, who told him it would be the last change — a curious involvement by an owner in the on-field decision-making.

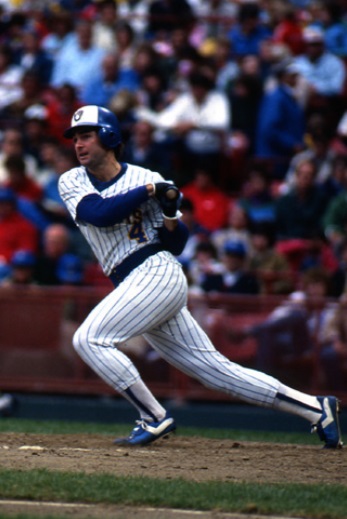

The team started the season slowly, and, with the Brewers floundering in fifth place on June 2, Dalton replaced Rodgers with Harvey Kuenn. Energized, Harvey’s Wallbangers posted a 25-11 record before the All-Star Game and grabbed a share of first place in the East Division. The Brewers battled Baltimore down the stretch, and won the division title with a 95-67-1 record on the season’s final day when Yount homered twice and veteran right-hander Don Sutton stopped the Baltimore Orioles. In an injury-free year, Molitor played in 160 games, led the league with 136 runs scored, stole 41 bases, and collected 201 hits, third in the league behind teammates Yount (210) and first-baseman Cecil Cooper (205). He was positioned to lead the Brewers into their first League Championship Series.

The American League West champion California Angels quickly gained the advantage when they jumped out to wins in the first two games, at Anaheim, despite Molitor’s inside-the-park home run in Game Two. The Brewers bounced back when the best-of-five series moved to Milwaukee, and they won the next three games at home. Molitor homered again, this time hitting one over the fence at County Stadium. For the series, Molitor keyed the Brewers offense by slugging .684, scoring four runs and driving in five.

Milwaukee opened the 1982 World Series at Busch Stadium, home of the National League champion St. Louis Cardinals. In the first game, Molitor set a fall classic record with five hits, all singles, to lead the Brewers to a 10-0 win. Cardinals’ manager Whitey Herzog was surprisingly dismissive of Molitor’s feat: “I ain’t runnin’ down Molitor. . . . he’s a heck of a ballplayer, but he had only one line drive. He had three infield singles and a broken-bat bloop. Nothin’ you can do to stop things like that.”32 After the Cards won the next two games, Milwaukee captured Games Four and Five in Milwaukee. But a fourth win proved elusive. Back home at Busch, the Cardinals won Game Six 13-1. Molitor, who hit .355 for the Series, collected two hits in Game Seven, but the Cardinals won 6-3 behind Joaquin Andujar and Bruce Sutter.

After their 1982 season, the Brewers suffered a letdown in 1983. Molitor, who signed a five-year $5.1 million contract before the season, injured his wrist swinging a bat in May. With the sore wrist, Molitor struggled through the worst slump of his career, a 2-for-41 stretch in which he went hitless in the last 25 at-bats.33 Near the end of the slump, Molitor missed 10 games as he rested his wrist. He batted .270 in 152 games, and the team fell to fifth.

During the season, Molitor’s old cocaine dealer, Tony Peters, was arrested. Molitor and his attorney negotiated immunity from prosecution and a commitment that, in exchange for answering all the investigators’ questions, he would not be called to testify at the trial unless absolutely necessary. In the end, Molitor was not forced to testify when Peters went to trial, and he avoided punishment from the baseball authorities as well, but his name and those of four other players came out in public early in the 1984 season at the trial.34

In the spring of 1984, Molitor was diagnosed with a slight tear in the medial collateral ligament in his right [throwing] elbow. He opened the season limited to designated-hitter duties and in late April tried a few games at third base. The elbow, however, was growing increasingly sensitive, and with Molitor hitting just .217 on May 1, the Brewers shut him down for season-ending Tommy John surgery. (Named after Tommy John, a pitcher who successfully resumed his career after this surgery, the procedure consists of replacing a ligament in the elbow with a tendon from elsewhere in the body.) Milwaukee, just two years removed from a World Series appearance, slid to last place in the American League East, 36½ games behind the Detroit Tigers. After the season, Molitor’s wife, Linda, gave birth to the couple’s daughter, Blaire.

Bamberger returned to the Brewers’ helm for the 1985 season, and he returned Molitor to third base and the leadoff position in the batting order. Bamberger was concerned about Molitor’s elbow early in the season and tried to play him no more than four games in row in the field.35 The elbow responded well, however, and Bamberger played Molitor at third base in 135 games. On July 2, Molitor doubled and scored the winning run against Boston for his 1,000th hit. Shortly thereafter, he played in the All-Star Game in Minneapolis with fellow St. Paul natives Dave Winfield and Jack Morris. His season appeared to be relatively injury-free until the end of August, when he missed two weeks with a sprained ankle.

Molitor suffered through another injury-plagued season in 1986. He tore his hamstring on May 9 charging a bunt in Anaheim. He hit a home run when he returned on May 30 but played in just three games before he aggravated the injury and went back on the disabled list. Molitor returned on June 17 for two games before again tearing his hamstring chasing a fly ball while playing left field.36 He came back on July 9 as the designated hitter; later that month the team moved him back to third, and Molitor played the rest of the season relatively injury-free. In one of the best games of his career, on August 19, Molitor led the Brewers to a 5-3 win in Cleveland by slugging two home runs and two doubles. He finished the year with a .281 batting average in 105 games and unexceptional on-base and slugging averages. At this point in his career Molitor’s star had begun to dim a little: he was now 30 years old, three years removed from playing more than 140 games in a season and four years removed from hitting .300.

Milwaukee started the 1987 season red-hot, tying the modern major-league record with 13 straight wins from the opening bell. Molitor helped key the streak by batting .395 in the first 20 games, 18 of them Brewers wins. Unfortunately, the injury bug struck once more when he was caught in a rundown between third and home and again tore his hamstring. Out four weeks, he came back but then missed games with groin and elbow injuries before re-injuring his hamstring.

When Molitor returned to the lineup on July 16 at home against California he had one hit, a double in four at-bats. Now limited to designated-hitter duties, over the next couple of weeks as Molitor consistently rapped out hits, he began attracting attention for his consecutive-game hitting streak. Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak has long been one of the most venerated streaks in sports, and even getting within shouting distance of this mark attracts enormous attention. As the pressure on Molitor mounted, he tried to keep the streak in perspective. “When you start a streak like this you’re preparing for the end, anyway,” Molitor said as the streak reached 34 games. “Initially I’ll be disappointed. It’s a unique opportunity to have a streak go on like this. But it shouldn’t take me long to get over it. It won’t be like the world came out from under me.”37 In Milwaukee on August 23, Molitor went 1-for-4 against Kansas City to raise the hitting streak to 38 games and pass Tommy Holmes for the seventh-longest streak in major-league history.

Three nights later Molitor was at home against Cleveland and going for his 40th consecutive game with a hit, which would tie Ty Cobb for sixth on the all-time list. Hitless in his first four at-bats, Molitor was on deck in the 10th inning when Rick Manning singled home the winning run. The fans were unnaturally subdued as the winning run crossed the plate, and Molitor joked about putting his hands up in the air: “People thought I was telling Mike [Felder] to score without sliding. What I was really doing was telling him to go back to third.”38 He also remembered the response from the fans: “When I headed for the dugout, the crowd got on its feet and gave me an ovation. That was probably the most emotional moment of the streak for me.”39 Molitor’s 39-game hitting streak was one of the longest in baseball history. Only Joe DiMaggio, Pete Rose, George Sisler, and Ty Cobb crafted longer streaks in modern baseball; Willie Keeler and Bill Dahlen did so in the 1890s.

Buoyed by the streak, Molitor turned in his best season statistically. He batted .353, second in the American League to Wade Boggs. He led the league in doubles with 41 and runs scored with 114, an astounding accomplishment considering he played in only 118 games. He also stole a career-high 45 bases and during the streak became the 33 rd major leaguer to steal second, third, and home in the same inning. His on-base percentage of .438 and slugging average of .566 were by far the highest of his career; his on-base percentage plus slugging average (OPS) of 1.003 was the league’s second best. For his accomplishments, Molitor finished fifth in the American League Most Valuable Player Award voting and received the league’s Joe Cronin Award for significant achievement and the Hutch Award as Comeback Player of the Year.40

After offseason arthroscopic surgery on his elbow, Molitor signed a two-year, $2.8 million contract, laden with bonuses based on games played.41 Relatively healthy, the Ignitor started the 1988 season as a designated hitter but soon reclaimed his spot at third. Molitor was named the starting American League second baseman in the All-Star Game, despite appearing in only one game at the position. At the end of the 1987 season, Molitor had been moved over to second base briefly, and that was where he was placed on the ballot for 1988. Star second baseman Julio Franco was bitter over Molitor’s starting berth: “The guy’s played only one game at second and he deserves to go more than me?”42 For the season, despite a nagging hamstring problem, sore wrist, and aching elbow, Molitor earned his playing time bonus by appearing in 154 games.

Molitor began the 1989 season on the disabled list with a dislocated finger, but he recovered quickly and joined the team in mid-April. He remained healthy throughout the remainder of the season and again received his performance bonus when he played in 155 games. In another strong season, despite one of the longest slumps of his career after the All-Star break, Molitor hit .315 with 27 steals. A regular at third base through the bulk of the season, he was switched to second near its conclusion by manager Tom Trebelhorn. The Brewers had two young shortstop prospects, Bill Spiers and Gary Sheffield, and Trebelhorn wanted to get them both into the lineup, one at short, the other at third.

Before the 1990 season, Molitor reached an agreement with the Brewers for a three-year, $9.1 million contract, then one of the largest in baseball, and along with his friend Yount, the second $3 million-plus salary on the club. Only one other team, the Oakland Athletics, had two $3 million-a-year players, and some questioned the Brewers’ wisdom on account of Molitor’s injury history. In fact, 1990 did become one of Molitor’s more frustrating seasons. Heading into spring training the Brewers’ infield was completely unsettled. Molitor, Sheffield, Spiers, Gantner, and Dale Sveum, the starting shortstop in 1987 and 1988, were all vying for three positions (second, third, and short). Unfortunately for the Brewers, as the injury bug bit, the Brewers actually found themselves with too few alternatives, not too many.

The 33-year-old Molitor was bothered by a sore shoulder in spring training, then fractured his thumb. He missed a month, and when he returned Trebelhorn put him at second to reduce the strain on his shoulder.43 In mid-June, Molitor suffered a fractured finger when he caught his hand in the glove of Cleveland’s Brook Jacoby and missed another six weeks.44 He returned at the end of July but was unable to throw because of the sore shoulder. Trebelhorn shifted him to first base, which riled regular first baseman Greg Brock and triggered his agent complaining to Dalton.45 Brock’s unhappiness only added to an already restless clubhouse — Sheffield, for example, wanted to be a shortstop, not a third baseman — and the struggling team dropped to sixth place after a .500 finish the year before. Molitor hit .285 in only 103 games, and his 1990 season ended prematurely when he collided with Jim Gantner in the final week. Already slated for shoulder surgery, he underwent a separate surgery on his forearm to repair the injury.

Molitor returned to full-time duty in 1991 but, no longer able to throw, was now limited to designated hitter and first base. For some reason Molitor flourished as a designated hitter — his position during the 39-game hitting streak — and over the remainder of his career he had some of his best seasons despite his advanced age (he turned 35 in August). On May 15 in Minnesota, Molitor hit for the cycle, and later in the year he singled off Bret Saberhagen for his 2,000th hit. Overall, belying his injury reputation, Molitor played in 158 games and led the league in plate appearances and at-bats. He performed well in all those opportunities: he batted .325 with a new career-high 216 hits, led the league with 133 runs scored, tied for the league lead in triples with 13, and finished eighth in OPS at .888.

Milwaukee brought in manager Phil Garner for 1992, and in late May the new skipper moved Molitor out of his familiar leadoff spot to third in the Brewers’ batting order. Molitor thrived in his new role. He batted .320 and drove in 89 runs, was named to the American League All-Star team, and led Milwaukee to a second-place finish in the American League East Division, the best by the Brewers in a decade. But the Brewers faced a difficult decision at the end of the season. Molitor, who had turned 36 in August, was a free agent, and Milwaukee’s ownership, which now behaved like a so-called small-market franchise, did not feel comfortable paying his market value.

Courted by the Red Sox and Angels, Molitor instead signed a three-year, $13 million contract with the world-champion Toronto Blue Jays on December 7.46 Back in Milwaukee, his former teammates lamented the loss of Molitor and the economics of the national pastime. “I think it stinks,” Yount said. “I think it’s a sad day when one of the best players in the American League wants to stay in a city with a team he’s been a part of for a long time, and the organization can’t afford to keep him. I’m going to sit down here and weigh out what should be done and how badly I really want to come back, knowing that a lot of the Milwaukee Brewers have left now.”47 His other close friend on the club, Gantner, reflected, “If Paul Molitor leaving the Brewers doesn’t show that the small markets are in trouble, nothing does.”48

While his teammates mourned, Molitor moved on with some trepidation but ready to embrace his new opportunity. He moved his family to Toronto and showed up at spring training ahead of schedule. Molitor, who opted to wear number 19 on his Toronto uniform in honor of Yount, joined a veteran team that had won the World Series the year before. He was slated to replace a St. Paul native, 1992 designated-hitter Dave Winfield, in the Blue Jays lineup (Winfield had moved on to the Twins), and join another hometown product, pitcher Jack Morris.

Molitor quickly endeared himself to the fans north of the border. In May, he hit .374 and earned American League Player of the Month honors. In July, Blue Jays manager Clarence “Cito” Gaston, the American League field boss for the All-Star Game by virtue of the World Series appearance, selected Molitor for the A. L. squad. The Ignitor validated Gaston’s confidence in his abilities by hitting .361 after the break, and he finished second in the league batting race behind teammate John Olerud. Molitor also drove in 111, scored 121 runs, and led the league with 211 hits.

In late September, Molitor returned to Milwaukee in triumph and hit a home run in Toronto’s division-clinching 2-0 win at County Stadium. The next morning, Molitor awoke to find the Milwaukee Journal printing excerpts from agent Ron Simon’s titillating book recounting Molitor’s drug abuse and detailing his contract negotiations.49

Molitor was able to set aside the resulting uproar for the postseason. In the American League Championship Series opener in Chicago he collected four hits, including a two-run homer, in Toronto’s win, then followed up with two more hits in Game Two as the Blue Jays won again. Chicago captured the next two games, in Toronto, before the Jays won Game Five at Skydome and Game Six in Chicago. In the latter Molitor’s ninth-inning triple plated a couple of insurance runs in a 6-3 victory. For the series Molitor hit .391 and drove in a team-high five runs.

Set to appear in his second World Series, Molitor became the center of speculation. The Phillies and Jays split the two opening games in Toronto, and the question of the hour was how Cito Gaston would use Molitor in Philadelphia, the National League city, where he was unable to employ a designated hitter. In a gutsy decision, against the Phillies’ left-handed pitcher Danny Jackson, Gaston benched left-handed-hitting John Olerud, the league batting champion, in favor of Molitor, who had played just 23 regular-season games at first base. The move paid off. Molitor, the third hitter in Toronto’s order, drove in two runs with a triple in the first inning and scored on Joe Carter’s sacrifice fly. He later slugged a solo home run and a single in a 10-3 win.

For Games Four and Five Gaston decided to risk Molitor’s weak throwing arm at third base in place of the light-hitting Ed Sprague. Gaston felt he could run this risk because the Phillies were mostly a left-handed-hitting team. As it turned out, Molitor threw over to first base only three times in the two games, and all the throws were on target.50 Game Four itself was a slugfest. The Jays outlasted the Phillies 15-14 in the longest nine-inning and highest-scoring game in World Series history. A day later, Philadelphia’s Curt Schilling shut out Toronto to send the Series back to Skydome.

Game Six was a classic. Molitor tripled, drove in the game’s first run, and scored on a sacrifice fly by Carter. In the fifth inning, to the chant of “MVP, MVP” (for Most Valuable Player) from Skydome fans, Molitor slammed a solo home run that gave Toronto a 5-1 advantage.51 But the Phillies battled back to take a 6-5 lead into the bottom of the ninth. Toronto’s Rickey Henderson walked to open the last half of that inning, and, one out later, Molitor smacked a hard line-drive single to center. With two on against Phillies closer Mitch Williams, Carter stepped in and pounded a line drive down the left-field line. The screaming liner slammed into the left-field bleachers. Molitor, leaping high, scored the winning run in front of Carter. When it was over Molitor let out a wave of emotion and wept on the field, later saying, “I’m not ashamed or embarrassed to admit that.”52

In the six-game series, Molitor collected 12 hits in 24 at-bats, including two doubles, two triples, and two home runs. He scored 10 runs and drove in eight and was named the World Series Most Valuable Player. “In Canada, when you say PM they think of prime minister, but now they might start thinking Paul Molitor!” color analyst Tim McCarver quipped during the TV broadcast. Molitor almost achieved the rare feat of winning the MVP trophy for both the World Series and the regular season, for which the writers voted him second in the MVP balloting.

Winfield had parted ways with the Jays after one season and a World Series title, but Molitor, with two years remaining on his contract, stayed in Toronto. Once the 1994 season began Molitor again turned in a stellar, injury-free year. On July 5 in Minnesota he hit the second grand slam of his career. Overall, he led Toronto with a .341 batting average, the sixth best mark in the league, and in runs, hits, total bases, doubles, and stolen bases. But Toronto finished the strike-shortened season under .500. Molitor continued to put his reputation for fragility behind him as he led the league in games played with 115. He was one of several players, including Baltimore’s Cal Ripken Jr., who appeared in all of their teams’ games during the season, but the Jays played one more contest than any other team in the league. Molitor made just five appearances in the field, all at first base.

In 1995 Molitor appeared in 130 games, strictly as a designated hitter. The highlight of his season was August 26 and 27 when he put together eight hits in eight at-bats with back-to-back four-hit games. Including the 28th, he reached base on ten consecutive plate appearances. But overall Molitor turned in one of his worst seasons, and at the age of 39 his game appeared to be slipping.

His three-year contract now up, Molitor became a free agent at the end of the season. He considered remaining in Toronto or returning to either Milwaukee or Minnesota. In the end he decided on Minnesota, and on December 5, 1995, he signed with the Twins for $2.025 million. Molitor started quickly; his early-season exploits including scoring five runs and driving in five in an April 24-11 win over the Tigers. Later he put together a five-hit game against Toronto in a 6-4, 11-innning win.

On September 16, 1996, at Kansas City’s Kauffman Stadium, Molitor singled in the first inning, the 2,999th hit of his major-league career. In the fifth inning, he hit a drive to right field off Jose Rosado and ended up on third base to become the first major leaguer to register a triple for his 3,000th hit. “I don’t know much about that young man [Rosado], but I know he did not try to avoid being the one who gave up my 3,000 th hit,” Molitor said. “I know he shook off a couple of signs and threw fastballs — saying, ‘If you’re going to get it, you’re going to get it.’”53 George Brett and Molitor’s friend Robin Yount were among those on hand to see him join them in the 3,000 hit club. The milestone hit came three years to the day after Winfield had collected his 3,000th hit, also for the Minnesota Twins, and the two became the first two players from the same hometown to accomplish the feat.

Molitor, the fourth oldest player in the league, appeared in a career high 161 of Minnesota’s 162 games for manager Tom Kelly. He batted .341, third in the American League behind Alex Rodriguez and Frank Thomas. He led the league in hits with 225 — becoming the oldest player to ever lead the league in hits54 — drove in a career high 113 runs and scored 99.

After the season Molitor chose to remain in Minnesota and signed a two-year contract with the Twins for a substantial pay increase in recognition that his skills had not yet eroded. Unfortunately, the injury bug bit again early in the season. Molitor returned to the disabled list for the first time since 1990 after he sprained his left wrist and strained his abdominal muscle in a home-plate collision on April 13 with Kansas City’s Mike Macfarlane.55 He rebounded to have a pretty good season, including five hits in a game against Oakland. He wound up the year hitting .305 with 10 home runs and 89 runs batted in. Molitor returned to the Twins in 1998 for his final season. Just two weeks shy of his 42 nd birthday, on August 8 against Baltimore, he turned the five-hit trick again and stole his 500 th base.

In retirement, honors poured his way. On June 11, 1999, Molitor returned to County Stadium, where the team retired the number 4 uniform he had worn for 15 years as a Brewer. That summer, he ranked number 99 on The Sporting News’s list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players and was a finalist for Major League Baseball’s All-Century Team.

Although Molitor knew he wanted to remain in baseball after retirement, he turned down an opportunity to join Milwaukee’s front-office or field staff — his first year off he just wanted to enjoy life. To keep his hand in the game Molitor worked part-time with the Twins broadcast team; he also golfed and went to Bruce Springsteen concerts around the world.56 With his transition year out of the way, Molitor joined the Twins as bench coach for the 2000 season — principally to help with baserunning and the mental approach to hitting — with the expectation of eventually becoming a big-league manager. He turned down an offer from the Toronto Blue Jays to become a roving minor-league hitting instructor and de facto heir apparent to manager Jim Fregosi. The Blue Jays had been after Molitor for some time; prior to the 1998 season they had offered him the manager’s position in either a standard or player-manager role. At the time Molitor turned the Blue Jays down to finish his playing career at home in Minnesota and because he thought he might need more seasoning before becoming a major-league manager.57

After the 2000 season, Toronto again offered Molitor the managerial position, which he again declined. He did not want to uproot his wife and high-school-age daughter; furthermore, veteran Twins manager Tom Kelly had just signed a one-year extension, and Molitor was likely next in line.58 So he remained with the Twins as bench coach for the 2001 season. As expected, Kelly retired after the season, and Molitor and Ron Gardenhire, emerged as the finalists to be Minnesota’s next manager. In early December, however, Molitor withdrew from consideration because of the uncertainty surrounding the potential contraction of the Twins. At the time Major League Baseball was actively negotiating to eliminate two major-league franchises, one of which was presumed to be the Twins. In the words of his agent, Ron Simon, Molitor “feels the situation’s so unsettled that he’d rather not be involved with it right now.”59 While in Milwaukee, Molitor had become quite friendly with Brewers owner Bud Selig. Now baseball’s commissioner, Selig had reportedly warned Molitor that contraction of the Minnesota franchise was likely.60

With the uncertainty of contraction and his daughter a senior in high school, Molitor elected to take the year off for some rest and relaxation.61 Molitor missed baseball, however, and in 2003 he took a job with the Twins as a roving minor-league instructor. Seattle Mariners general manager Pat Gillick, who had recruited Molitor to Toronto back in 1993 and unsuccessfully chased him for other positions since his retirement, now targeted him to be Seattle’s batting coach. This time Molitor accepted. One year was enough, however, and after the season the financially secure Molitor — he earned nearly $800,000 in 200462 — moved back to Minnesota to resume the less stressful job of a roving minor-league coach.

In semi-retirement Molitor’s personal life became uncomfortably complex. In 2003 Molitor and his longtime wife, Linda, divorced. Molitor had fathered a son with Joanna Andreou a couple of years earlier and paid child support. While the Molitors were legally separated, Molitor fathered a daughter with another woman. In early 2004, Molitor married the child’s mother, Destini, and he and his second wife have two children. Molitor’s behavior and subsequent divorce from Linda caused such hard feelings that his ex-wife and daughter almost did not attend his Hall of Fame induction ceremony. His difficult personal life may have also contributed to his unwillingness to commit to a more prominent baseball job.63

On January 6, 2004, in his first year of eligibility, Molitor was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, garnering 85.2 percent of the possible votes. On July 25, before a crowd of 15,000 on a partly-sunny Sunday afternoon in Cooperstown, New York, Molitor and pitcher Dennis Eckersley were inducted into the Hall. A clearly emotional Molitor thanked the most important people in his life and talked about some highly personal issues, including his son, Joshua, and his drug use. He also reviewed his career and reminisced: “The baseball memories are great, but when you think about your career, the people memories are even better.”64

After nine years as the Twins minor league baserunning and infield coordinator, Molitor decided to rejoin major league baseball in a more active capacity. In 2014 he accepted a job on the Twins major league field staff under manager Ron Gardenhire overseeing baserunning, bunting, infield instruction and positioning, plus assisting with in-game strategy.65 Gardenhire was let go after season, the Twins fourth in a row with 70 or fewer wins, and the team embarked on an extensive manager search, led by GM Terry Ryan.

After a process Ryan dubbed, “our five-week ordeal,” in November 2015 the Twins hired Molitor to manage the club on a three-year contract.66 Many former teammates and coaches raved about his understanding of baseball. “He was as aware as player I ever saw,” former manager Tom Trebelhorn recalled.67 The other finalist for the job was reportedly Torey Lovullo, manager of the Arizona Diamondbacks as of 2019.68 Molitor became only the third man in history (with Ted Williams and Ryne Sandberg) to get his first managerial opportunity after being elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame (excepting those with interim tags).

Despite the team’s recent struggles, Molitor and Ryan both felt the club had some talent, and they were not in a rebuilding mode. “Things can change very dramatically at this level, very quickly…I want [players] to believe we can win now. I hope to set that tone right away.”69 He also offered some insights on his philosophy of managing, “Little mistakes left uncorrected lead to big mistakes. I firmly believe that. There’s a right way to do things, and if you don’t emphasize the fundamentals, you have to play that much better to overcome it. And we don’t have that luxury.” Later adding, “You watch a team like the San Antonio Spurs or the New England Patriots, these teams somehow are able to create a team-first atmosphere. When young players arrive, it’s about ‘Do I belong, can I stay, will I make a living?’ Well you have to teach them that if you buy in to what we’re doing collectively, if that becomes your focus, it’s going to work out for you individually, too.”70 And in fact, Molitor delivered in 2015. The team jumped to 83 wins, and Molitor finished third in the AL Manager of the Year Balloting and was named AL Manager of the Year by The Sporting News.

Unfortunately, 2016 was a disaster. The team lost a Minnesota record 103 games as several youngsters were either injured or failed to take the expected step forward, and the pitching disintegrated. Owner Jim Pohlad reorganized the front office, replacing longtime baseball man Ryan with Derek Falvey, a 33-year-old analytically-savvy wunderkind from the Cleveland Indians. And although Falvey had free rein to restructure the team as he saw fit, Pohlad let him know the one exception was that he needed to keep Molitor for at least one more season.71 Both sides put a happy face on the marriage, but Falvey forced some changes on the coaching staff, and Molitor would have a much different relationship with the front office moving forward.

The team bounced back remarkably in 2017. Since 1901 only 14 of 143 teams had finished above .500 the season after losing at least 100 games. The Twins bucked this trend, winning 85 games and securing the second wild card slot. There were no real weak spots in the lineup, which could also boast some depth, and Molitor juggled a less-than-stellar pitching staff. For the team’ and given a new three-year contract.

Once again, however, the Twins could not build on their momentum, backsliding to 78 and 84 in 2018, and the team bounced Molitor after four years at the helm. “It’s about where our club is for the present and the future. This wasn’t about our record this year.” Falvey said. “We just felt a change in style with some of these younger players could be of benefit for us.”72 Minneapolis sportswriters speculated on other, more concrete, reasons: Falvey wanted to hire someone of his own choosing; the young players were not developing as quickly as hoped; and there was some friction between some of Molitor’s holdover coaches and the new-school coaches.73

Tactically, Molitor issued intentional walks at a rate above the league average every season, leading the league in 2018. He also used the sacrifice bunt more than average and attempted relatively few steals of third. Over the last two years of his tenure, Molitor opened the game with the platoon advantage significantly more often than his peers.74 As of 2019 Molitor was “enjoying some downtime,” and considering what to do next in baseball.75

Throughout his career, Molitor earned recognition for his involvement with several charities and received a number of awards for his good works. For 1997 he was awarded the Lou Gehrig Award by Phi Delta Theta, Gehrig’s fraternity at Columbia University, for “someone who best exemplifies the giving character” of Gehrig. Molitor was praised for sponsoring “a program which has allowed thousands of youngsters, senior citizens, and needy adults to attend big-league games, and [being] actively involved in fund raising to combat several diseases.”76 The next year Molitor received the Branch Rickey Award, given by the Rotary Club of Denver and selected by baseball notables and Rotary district governors to recognize baseball players who “exemplify the Rotary ideal of ‘Service Above Self.’”77 As of 2019 Molitor supported several charities including Starkey Hearing Foundation, Camp Heartland, Friends of St. Paul Baseball, and Salvation Army.78

For 21 seasons, Paul Molitor was a great player and a quiet leader. “When I first got to Milwaukee my locker was right next to Paulie’s,” remembered one-time teammate Cal Eldred. “He was an unbelievable teammate. Guys like him and Robin and Gumby [Jim Gantner] just went about their business every day. They didn’t say a lot but when they did, everybody would listen.”79 Molitor achieved his dream, articulated many years earlier in his high-school yearbook, of playing pro baseball and working with people. And Molitor not only played professional baseball, but he became a star: 15 years in Milwaukee as one of the city’s biggest celebrities, a world championship in Toronto, and a final few years in front of his hometown fans in Minnesota. Along the way he used his fame to work with people in his numerous charitable endeavors.

Last revised: May 31, 2019

An earlier version of this biography appeared in SABR’s “Minnesotans in Baseball” (Nodin Press, 2009), edited by Stew Thornley.

Notes

1 Richard Hoffer, “Career Move,” Sports Illustrated, March 29, 1993: 45.

2 The Sporting News, March 6, 1989: 26.

3 Seattle Times, July 25, 2004.

4 Two websites, http://retrosheet.org and http://baseball-reference.com, are essential for verifying and generating game and seasonal information.

5 Unless otherwise noted, the two main sources for Molitor’s early life are Bill Koenig, USA Today Baseball Weekly, April 17-23, 1996, and Jim Souhan, Minneapolis Star Tribune, February 18, 1996.

6 Correspondence with Tony Leseman, Cretin-Derham Hall Development & Alumni/ae Officer, August 4, 2008.

7 Hoffer, op. cit.; Aschburner, Steve. “Strictly Business,” Inside Sports, June 1994.

8 Rich Marazzi, “Batting the Breeze,” Sports Collectors Digest, February 26, 1993: 190.

9 Correspondence with Tony Leseman, Cretin-Derham Hall Development & Alumni/ae Officer, August 4, 2008.

10 Koenig, op. cit.

11 Stewart Broomer and Paul Molitor. Good Timing, Toronto: ECW Press, 1994: 17.

12 St. Paul Pioneer Press, September 18, 1996.

13 The Sporting News, August 12, 1978: 3.

14 University of Minnesota press release, June 17, 1976.

15 1976 Minnesota Baseball.

16 Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 26, 2004.

17 St. Paul Dispatch, July 7, 1976.

18 Minneapolis Tribune, April 12, 1977.

19 W.C. Madden, Baseball’s First-Year Player Draft: Team by Team Through 1999: 195.

20 Minnesota Daily, July 28, 2004; Minnesota Daily, February 3 and July 28, 1994.

21 Hoffer, op. cit.

22 C.C. Johnson Spink, Official Baseball Guide for 1978, The Sporting News; Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff. Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 3rd Edition. Durham, N.C.: Baseball America, 2007: 579.

23 Tom Skibosh, “Paul Molitor: To Catch A Thief,” Milwaukee Scorebook, 2nd Edition, 1979: 9.

24 The Sporting News, October 7, 1978: 27.

25 Mik Gonring, “Molitor & Yount: Opposites Really Do Attract,” Milwaukee Brewers Program, June 1979: 50.

26 Simon, Ron. The Game Behind the Game: Negotiating in the Big Leagues. Stillwater, Minnesota: Voyageur Press:158.

27 New York Times, August 19 1985; Simon, op. cit.: 158.

28 Simon: 153-159.

29 Daniel Okrent, Nine Innings. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1985: 68-69; The Sporting News, April 4, 1981.

30 Okrent, op. cit.: 70.

31 The Sporting News, February 13, 1982: 40.

32 The Sporting News, October 25, 1982: 14.

33 The Sporting News, June 27, 1983: 23; http://baseball-reference.com

34 Simon, op. cit.: 159-160.

35 The Sporting News, May 13, 1985: 24.

36 Broomer, op. cit.: 66.

37 New York Times, April 21, 1987.

38 The Sporting News, March 28, 1988: 8.

39 John Kuenster, “With 3,319 career hits, Paul Molitor merits Hall of Fame Status,” Baseball Digest, February 2004.

40 Broomer, op. cit.: 89.

41 Broomer, op. cit.: 89.

42 The Sporting News, July 10, 1989: 13.

43 The Sporting News, May 14, 1990: 16

44 The Sporting News, July 2, 1990: 13.

45 The Sporting News, August 13, 1990: 10.

46 Simon, op. cit.: 182-183.

47 Broomer, op. cit.: 112.

48 Broomer, op. cit.: 112.

49 Broomer, op. cit.: 143-145.

50 The Sporting News, November 1, 1993: 17.

51Broomer, op. cit.: 176.

52 Tom Verducci, “The Complete Player.” Sports Illustrated, November 1, 1993: 28.

53 Minneapolis Star Tribune, September 17, 1996.

54 Tim Kurkjian, “No Asterisk Necessary,” Sports Illustrated, September 9, 1996: 76.

55 The Sporting News, April 28, 1997: 37.

56 Minneapolis Star Tribune, April 30, 1999, November 24, 1999.

57 The Sporting News, November 10, 1997: 42; November 17, 1997: 51; November 16, 1998: 59; December 6, 1999: 74.

58 The Sporting News, October 23, 2000: 59.

59 Associated Press, http://espn.go.com/mlb/news/2001/1203/1289316.html.

60 The Sporting News, April 29, 2002: 32.

61 Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, August 13, 2002.

62 Toronto Sun, September 16, 2005.

63 Internet Movie Database, http://www.imdb.com; Minneapolis Star Tribune, February 15, 2004, October 13, 2003, November 20, 2005; Toronto Sun, September 16, 2005.

64 Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 26, 2004.

65 2018 Minnesota Twins Media Guide: 14.

66 Phil Miller, “Here to Win,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, November 5, 2014.

67 Phil Miller, “A Mind for Managing,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, February 22, 2015.

68 Phil Miller, “Twins Offer Molitor Managerial Reins,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, November 2, 2014.

69 Phil Miller, “Here to Win,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, November 5, 2014.

70 Phil Miller, “A Mind for Managing,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, February 22, 2015.

71 Phil Miller, “Falvey More Than Happy to Keep Molitor at the Helm,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, November 8, 2016.

72 Phil Miller, “Class Dismissed,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, October 3, 2018.

73 Jim Souhan, “Falvey, Levine Offer Reasons That Leave a Lot of Guesswork,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, October 3, 2018; LaVelle E. Neal III, “Living in a Future Without Molitor,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, October 3, 2018.

74 Baseball-reference.com; Bill James Handbook, ACTA Publications, 2016 -2019 editions.

75 LaVelle E. Neal III, “Molitor Also Staying Close to Home,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, November 13, 2018.

76 New York Times, February 13, 1998.

77 The Rotarian, April 1999.

78 “Alumni Support These Causes and Charities,” https://www.mlb.com/twins/community/player-charities

79 Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 24, 2004.

Full Name

Paul Leo Molitor

Born

August 22, 1956 at St. Paul, MN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.