St. Louis Cardinals team ownership history

This article was written by Mark Stangl

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

The St. Louis Cardinals won a World Series championship in 2006, their first season at the new Busch Stadium. (Kevin Ward/Flickr.com. Used by permission: CC BY-SA 2.0.)

Introduction

The St. Louis Cardinals have achieved a level of success in Major League Baseball that has been outdone only by the New York Yankees. Through the 2021 season, the franchise has won 11 World Series, 19 National League pennants, four American Association pennants, and the 1886 World Series versus the Chicago White Stockings — a winner-take-all battle with bragging rights included. This level of success has been the catalyst for the franchise to be identified as a major asset to the city of St. Louis and the surrounding metro area. The Cardinals are as much a part of the community fabric as the “Birds on the Bat” worn on their uniform.

For the fans known as Cardinal Nation, following the Redbirds is a religion passed from generation to generation. Proudly wearing their Cardinal red, they have cheered with relish their favorite players, in victory or defeat. Reciting the names of Hall of Famers such as Rogers Hornsby, Dizzy Dean, Stan Musial, Enos Slaughter, Bob Gibson, Lou Brock, and Ozzie Smith, plus members of the Cardinals Hall of Fame such as Willie McGee, Jim Edmonds, Scott Rolen, and current players Yadier Molina and Adam Wainwright, is akin to reciting the Litany of the Saints before a Catholic Mass.

In nearly 150 years, the team’s owners have been as varied as the fans. Click on a link below to scroll down to that chapter.

- Chris Von der Ahe (1882-1898)

- Robison Brothers (1899-1911)

- Helene Hathaway Robison Britton (1911-1916)

- “The Cardinal Idea” (1917-1919)

- Sam Breadon (1920-1947)

- Fred Saigh Jr. (1948-1952)

- Anheuser-Busch (1953-1995)

- Bill DeWitt Jr. (1995-present)

Chris Von der Ahe

St. Louis Brown Stockings (American Association), 1882

St. Louis Browns (American Association) 1883-1891

St. Louis Browns (National League) 1892-1898

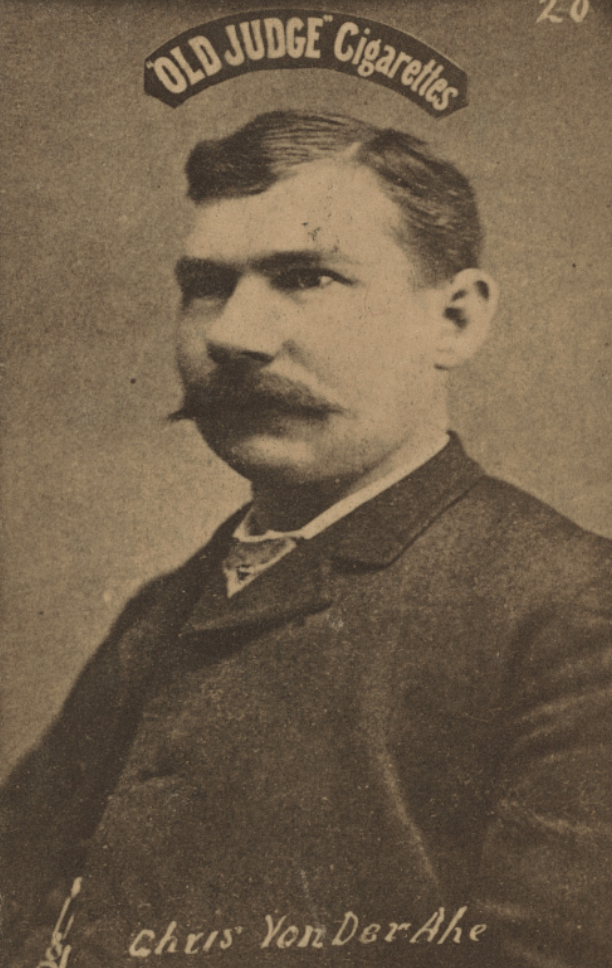

Chris Von der Ahe was born in Hille, Germany in 1851. He came to St. Louis by way of New York in 1867 and found work as a grocery clerk. He married Emma Hoffman, a native Missourian of German descent, in 1870 and they had a son, Edward. The grocery business was very successful, serving the German residents and quarry workers. It became so profitable that the ambitious Chris bought the store from his partner for $1,125 in 1872. He expanded the business by including a saloon and a beer garden, located a block and a half from the Grand Avenue Grounds, at the corner of Grand and Dodier, then the premier baseball site in St. Louis. The saloon became a popular destination for politicians, fans and the ball players before and after the games.1

Chris Von der Ahe was born in Hille, Germany in 1851. He came to St. Louis by way of New York in 1867 and found work as a grocery clerk. He married Emma Hoffman, a native Missourian of German descent, in 1870 and they had a son, Edward. The grocery business was very successful, serving the German residents and quarry workers. It became so profitable that the ambitious Chris bought the store from his partner for $1,125 in 1872. He expanded the business by including a saloon and a beer garden, located a block and a half from the Grand Avenue Grounds, at the corner of Grand and Dodier, then the premier baseball site in St. Louis. The saloon became a popular destination for politicians, fans and the ball players before and after the games.1

Von de Ahe started buying real estate in the neighborhood. He got involved in politics, becoming a party activist and a supporter of mayoral candidates.2 St. Louis was a fast-growing city, reaching a population of 350,518 in the 1880 census and German ancestry figured prominently in the city’s political and social life.

Professional baseball made its debut in St. Louis in 1875. Two teams represented the city in the National Association that year, the Red Stockings and the Brown Stockings. The Red Stockings played at Red Stockings Park located at Gratiot at the west side of Compton Avenue in midtown St. Louis.3 The Brown Stockings were led, and substantially financed by $20,000 from the club’s president, J. B. C. Lucas. a St. Louis banker and grandson of Jean Baptiste Charles Lucas, who was a major developer of downtown St. Louis.4 Their home park was the Grand Avenue Grounds near Von der Ahe’s beer garden.

The Red Stockings generally used local amateur players hoping to outdraw their rival by pointing to the Brown Stockings’ use of imported talent. However, they paid the price for that decision when playing against their veteran opponents.5 After posting a 4-15 record by July 4, the Red Stockings ceased operations as a professional club but continued to play other amateur nines around the country for the remainder of the season. The Brown Stockings finished fourth with a roster that featured pitcher George Bradley, shortstop Dickey Pearce, outfielder Lip Pike and outfielder Ned Cuthbert. Troubled by gambling, players jumping from team to team, and teams refusing to complete their schedules, the National Association collapsed after the 1875 season. Lucas and the Brown Stockings moved to the new National League. Unlike the National Association, it was a league to be closely managed by the owners and run as a business.

Although the 1876 season didn’t end with a pennant, the Brown Stockings finished second, percentage points ahead of Hartford. Their own George Bradley pitched the League’s first ever no-hitter in St. Louis beating that Hartford squad 2-0 on July 15.6 For the 1877 season, the team fell below .500 and Lucas thought a house-cleaning was in order. Lucas signed four players from the Louisville team, which had ceased operations, and picked up others. Expectations for 1878 championship were high. But before they could ever don St. Louis togs, several of the Louisville players were suspended for life for their involvement in fixing games. The scandal soured St. Louis Base Ball fans on Lucas, whom they thought knowingly signed tainted players. Lucas was so disgusted with the innuendo that he and his associates shut down the Brown Stockings. 7

From 1878-1881, watching semipro teams at the Grand Avenue Grounds, was one place where St. Louis fans could go to get their base ball fix. Von der Ahe knew nothing about the game and was confounded by the enthusiasm of the fans. But he was very happy when players and fans came to his saloon for post-game drinks. Ned Cuthbert, who was now running a semipro team called the Brown Stockings, was a regular patron and became friendly with Von der Ahe. Before the 1880 season, Cuthbert approached Von der Ahe and asked him if he would front the money for the rent at Grand Avenue Grounds so that his Brown Stockings could play there. Von der Ahe would be repaid from profits of the games.8 Near the end of the season, Von der Ahe obtained a new lease on the ballpark, promising to make improvements to it with the hope of getting membership in the National League.9

That offseason, Von der Ahe formed the Sportsman’s Park and Club Association and improved the Grand Avenue Grounds with more seats and new buildings. The Association was composed of Von der Ahe, who was controlling shareholder with at least 51 percent, beer producer William Noelker, newspaperman Al Spink, saloon owner John Peckington, and Congressman John J. O’Neill.10 The first game at the renovated diamond was Sunday May 22, 1881.

According to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, “The preparations for the contest were very hurriedly made, the baseball diamond especially showing need of water and a roller. The infield was so rough that perfect play thereon was out of the question. In the positions assigned to the pitcher and catcher however a smoother state of affairs existed and the outfield recently mowed was all that could be desired.”

The game featuring two local semipro teams attracted 2,500 spectators.11 On October 23, 1881, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat used the name Sportsman’s Park for the first time in promoting a game at the diamond on Grand Avenue — a game between two semipro teams.12

The revenues from games for the 1881 season were divided with the Association members receiving the revenues from ticket sales of reserved seating plus concessions. The players’ share was based on the walk-up attendance. In the beginning, the player earned about $3.75 per game. As the season wore on, with judicious scheduling by Al Spink, the club’s secretary, and with the Brown Stockings playing winning baseball, growing attendance provided players with income between $150 and $175 per month.13

Von der Ahe was not happy that some of the players only showed up for the weekend games when attendance was largest. The club had to get fill-in players for the weekday games so the quality of play was not as good and the crowds were smaller. The players who missed those games argued that they had regular jobs and couldn’t risk losing them to play ball during the week. Von der Ahe ultimately kept only the players who could play full time. Spink obtained more players and the “New Brown Stockings“ finished a season that lasted into November.14

At the end of the 1881 season, the partnership split profits of almost $25,000 in a back room in Von der Ahe’s saloon. Seeing how owning a baseball team could increase profits as well as his prestige, Von der Ahe bought out the other partners for $1,800. The total value of the franchise was roughly $3,700.15 His first act as owner was to sign Charlie Comiskey, first baseman of the Dubuque Rabbits, to a new contract for $150 a month.16

Von der Ahe wanted to take his new team into an organized league. The established National League, however, required three things that the Brown Stockings owner couldn’t accept. The league banned Sunday baseball, alcohol sales, and required admissions cost at least 50 cents. As a result, Von der Ahe sought like-minded owners in cities that would allow Sunday games, 25 cent admissions and beer sales. They would cater to the working class rather than the privileged. He found such an owner in Denny McKnight of Pittsburgh and on November 2, 1881, they and owners in Baltimore, Cincinnati, Louisville and Philadelphia created the American Association. Von de Ahe was named a director on the Association’s Board.17

At Sportsman’s Park, Von der Ahe turned the right-field corner into a beer garden which included space for lawn bowling and a handball court. The beer garden required its own ground rule. Until the 1888 World Series, it was part of the playing field. The outfielder could go into the seats to retrieve a fair ball but had to throw it to a fielder in the pitcher’s box before a runner could be put out.18 In addition to the renovations Von der Ahe planned to have the park wired for electricity.19 He wanted Sportsman’s Park to be a multi-use facility, with space for track and field meets, soccer and lacrosse.20

The first game of St. Louis’ American Association season and first as the franchise occurred on May 2, 1882 at Sportsman’s Park against Louisville. Von der Ahe’s Brown Stockings honored the traditional name and came onto the field wearing crisp white uniforms with brown stockings and caps. Von der Ahe emphasized the connection by bringing in Ned Cuthbert as the manager. A crowd of 2,000 was treated to the franchise’s first win, 9-7. They were also entertained by Joseph Postlewaite’s band between innings. The band, which performed crowd favorites was conducted by umpire Charley Houtz, who pulled double duty.21

Focusing on maximizing beer sales at the ballpark, Von der Ahe delegated the procurement, training and discipline of players to his on-field managers. Cuthbert resigned due to ill health (consumption) in late September.22 To help him out financially, Von der Ahe had a benefit game and dinner for his friend.23

For 1883, Von der Ahe hired Ted Sullivan who had an organized, regimented way of running a ballclub. Von der Ahe felt the Browns, as they were now called, had lacked discipline in their first season. But Sullivan quickly antagonized the players with fines or threats of fines. Two players, Pat Deasley and Fred Lewis, attacked Sullivan after being accused of breaking curfew. The players had been drinking and playing pool after an August 11 game in Columbus. After a heated exchange, the two players chased Sullivan around the block and beat him. Both players were jailed by police and later released on bail. Von der Ahe found out but didn’t discipline Deasly or Lewis, who had been an expensive acquisition.24 Sullivan resigned, feeling unsupported by Von der Ahe and angry at the insinuation that he caused dissension among the players. To fill the vacancy, Von der Ahe named Comiskey manager for the rest of the season.25

Discipline issues didn’t disappear with a different manager for 1884. Instead of keeping Comiskey as player-manager, Von der Ahe brought in Jimmy Williams, the secretary of the American Association. Von der Ahe said price was no object as he would double the $45,000, he said he spent on the Browns.26 Again Fred Lewis was in the eye of the storm. He was arrested on the morning of July 2, 1884 accused of assaulting “a lady of the evening.” Upset with Lewis’ behavior during the heat of a pennant chase, the other Browns players wanted him off the team.27 Von der Ahe settled for a heavy fine, since Lewis was one his better players.28 Williams, tense and on edge as the play of the club deteriorated, resigned September 4. Charlie Comiskey for the second time in two years took over as interim manager.29

Despite the off-field issues, fan attendance was strong for Von der Ahe’s club, with 135,000 in 1882, 243,000 the following year and 212,000 in 1884, all higher than the National League average those three years. Von der Ahe said he had his own method of counting attendance not using turnstile count but of the number of barrels consumed. “Veil, Ve Sold so many barrels ve must have had a crowd of such and such size.”30 Newspapers loved to report Von der Ahe’s sayings in his heavy German accent.

In June 1883, Von der Ahe challenged an American Association rule with a popular gesture. The rule was “the visiting team, employees and umpires are guaranteed their monies if a game is called. The fans are NOT entitled to getting their money back.”31 That rule came into play on June 20 when rain delayed the game after a half inning of play. The game was called after a 30-minute wait. After the announcement around 200 irate fans stormed the ticket office and then Von der Ahe’s office demanding rain checks or their money. Von der Ahe, at first, pointed to the rule posted on the ticket window.32 The next day, feeling that the rule was unfair, he announced rain checks would be issued. “the fans of St. Louis won’t pay for what they don’t see.”33

Before the 1885 season, Von der Ahe took the interim tag off Charlie Comiskey. He felt that as player-manager, the first baseman could instill discipline off the field while playing winning baseball on it. Von der Ahe did his part by demanding players board in buildings he owned so he could keep an eye on them. Not missing an opportunity to make or save money, he garnished the players paychecks for room and board.34 Despite anger from some players, the Browns laid waste to the American Association from 1885 to 1888, winning four straight pennants. The pinnacle moment for Von der Ahe and the Browns was winning the 1886 World Series. It was a winner-take-all affair agreed to by Von der Ahe and Al Spalding of the Chicago White Stockings. The Browns bested the White Stockings four games to two.

Winning the last game at home on an extra-inning wild pitch touched off the fans:

“The wildest celebration prevailed, the crest multitude hanging around the scene of battle and making demi-gods of the brown-legged heroes. When the ball-players took their carriages, the people followed them and the scene of excitement was transferred to the central part of town,” reported the Chicago Inter-Ocean.35

Von der Ahe led the parade. As was his custom on big moments at the ballpark, he wore “a silk hat, his portly figure in his Prince Albert coat, striped trousers and spats trailing his two fawn-colored greyhounds.”36

Von der Ahe’s owner’s share came to $6,960.05 while there was $580.05 for each of the 12 players.37 The spoils of victory were displayed in the windows of Mermod & Jaccard Jewelery Company. “The magnificent solid silver Winan Trophy, … the World’s Champions banner and other victorious emblems of the Browns … have been placed in the windows so that all in the world that loves base ball and admires its champions can see what their merits have obtained for them.”38

The Browns, and especially Von der Ahe, became the toast of the town. The Browns’ owner took full advantage by throwing nightly parties at his saloon “which bugged the eyes out of North St. Louis” according to the St. Louis Star-Times. Asked why he threw all the parties, the Browns’ owner said, “money dos ist to spend.”39

The Browns got a “bump” in attendance from the World Championship as 244,000 fans, a 17 plus percent increase over 1886, turned the turnstiles to watch the Browns win a third consecutive American Association pennant. St. Louis could not win a second consecutive World Championship, though losing, to the Detroit Wolverines 10 games to 5.

The Browns’ championships also had ended the hopes of Henry V. Lucas, the brother of the J.B.C. Lucas who had owned the original Brown Stockings in the National Association. Henry Lucas had formed a team, called the Maroons, in the short-lived Union Association. The Maroons had signed some of Von der Ahe’s players and ran away with the association’s 1884 pennant. But the Maroons success revealed a severe lack of competitive balance in the Association and the league folded after that season.

Lucas wanted to stay in major league baseball and felt his team could compete in the National League. The league extended a membership to the Maroons for the 1885 season despite Von der Ahe’s protest that the National Agreement between the National League and the American Association said a second team couldn’t be put in a city if one was already there.40 The Maroons found stiffer competition in the National League, finishing last in 1885 and sixth in 1886. They were also outdrawn by the Browns in both seasons. The Browns’ season totals were greater than the National League average total attendance for those two years. The Browns also dominated exhibition series with the Maroons in those years. With St. Louis fans following a winner instead of Lucas’s poor team, the Maroons folded after the 1886 season.

With three consecutive American Association pennants and a World Series title, Browns players wanted to be compensated. After seeing the NL’s Chicago team sell two of its stars — catcher Mike “King” Kelly and pitcher John Clarkson — for $10,000 each, Von der Ahe saw he could get inexperienced players for less money. He felt Comiskey could get the best of their talents and still win in 1888. So, without telling Comiskey, he sold four of his stars — Doc Bushong, Curt Welch, Bob Caruthers and Dave Foutz — for $21,250 and three players. Comiskey was furious, but realized he would be hard pressed to find a player-manager position elsewhere to make his $8,000 salary. He stayed with Von der Ahe.

The 1888 St. Louis Brown Stockings won 92 games and won their fourth consecutive American Association pennant. However, they lost in the postseason World’s Series to the New York Giants of the National League. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

The fans were not as forgiving as Comiskey. The 1887 attendance would be the high water mark for the remainder of Von der Ahe’s ownership, as he would not be hesitant to sell players. With success, Von der Ahe became more and more vocal when the team wasn’t playing well. He did not worry about their feelings and was willing to interrupt play to call them out during games. He also liked to show them who was the “boss President.”41 The majority of the time Comiskey was able to defuse the situation and calm Von der Ahe down. When the team was winning pennants, it was easier to do.42

One of the times that Comiskey couldn’t defuse a volatile situation was the day before a game in Kansas City. Von der Ahe fined second baseman Yank Robinson $25 for using foul language while in uniform. Robinson had cursed a gatekeeper who wouldn’t permit delivery of a pair of padded pants Robinson had ordered for that day’s game. The offended gatekeeper went to Von de Ahe’s box and the owner climbed onto the field and confronted Robinson. Robinson said if Von der Ahe didn’t rescind the fine he would skip the team train to Kansas City that day. Robinson’s teammates supported him because they thought that no punishment should have occurred and they refused to board the train as well. Browns’ secretary George Munson eventually persuaded all except Robinson to take the evening train.43

Von der Ahe said the punishment was warranted because Robinson was in uniform and what he did was inexcusable, although he also said he wished he had disciplined Robinson in private. Still, Von der Ahe would not relent and Robinson would have to pay the fine despite players and fans asking the owner to drop it. Robinson was equally stubborn and said he would not pay it. Von der Ahe also complained that if all the fans who supported Robinson had come to the ballpark instead of telling him how to run his club there would be fewer empty seats. Von der Ahe said that the players who caught the late train would have to reimburse the club. He said he had already paid for the scheduled train including sleeping arrangements and it was not his fault that the players missed the earlier train.44

It was high-handed incidents such as this that fueled the creation of the Players League for the 1890 season. Led by New York Giants shortstop John Montgomery Ward, the Players League was formed to compete with the established National League and American Association teams. The objective of the PL was to provide its players with increased salaries which the established leagues limited through the reserve clause.45 Comiskey and a number of Von der Ahe’s players signed with the Chicago Pirates of the Players League.

Von der Ahe dismissed the idea the Players League could damage the American Association, and he had especially strong words for Comiskey.

“There is a mistaken impression, that it was due to Comiskey’s skill that the Browns were successful. That is not so. On the contrary he was a drawback to the team. He raised a number of rows in Brooklyn, Baltimore, Cincinnati and Philadelphia and … kept me in hot water,” Von der Ahe said. Comiskey “was of a very ugly disposition and could never gain the goodwill of his players. He is a good ballplayer, but … not the brains of the St. Louis Club, by long odds.” Still not finished, Von der Ahe added, “I think that he is the ungrateful of all men. … I raised his salary from seventy-five dollars a month to five thousand a season and an interest in my team. In return, for my kindness, he left me in the hour of need.” Von der Ahe claimed he had youngsters on the Browns that could play just as well for less money.46

Von der Ahe used six managers during the 1890 season, and virtually all teams in the three leagues lost money. The Players League folded and four Association teams failed. Comiskey came back to manage in 1891 for a $6,000 contract from Von der Ahe and $4,000 raised by Browns boosters.47

Von der Ahe expressed optimism for the 1891 season. “The American Association is on a stronger basis financially than it has been for years. Both Boston and Chicago will be represented with good clubs, while Philadelphia and Washington will have better teams than either city has in a long while.” 48 He was overly optimistic. The Chicago team would fold before the season started. In fact, 1891 was the tenth year of the Association and only Louisville and St. Louis had been in the league every year.

By the end of the 1891 season, it was apparent the American Association’s days were numbered.49 The National League, which had paid higher salaries to keep players from jumping to the Players League was pushing hard for a settlement which would allow it to bring salaries down. The League owners held the upper hand because their teams were on more solid financial footing than the Association clubs.50

On December 12, 1891, the American Association passed into history. The National League took in the Association teams from Baltimore, Washington, Louisville and Von der Ahe’s St. Louis Browns.51 St. Louis was given membership in the “new” League because the NL owners felt it was a “ far better baseball city” probably “more supportive of their team than Pittsburg or Cleveland” and “for baseball owners money counts for more than friendship or sentiment,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch said.52

Von der Ahe, who had wanted into the National League since he bought the Browns, pushed for Sunday baseball, 25-cent admissions and beer sales in St. Louis, Cincinnati and Louisville. He won those issues, but lost on others. All the Association clubs had to put their players in a pool, with the National League teams getting first choice at signing them. By not being allowed to protect its existing players, St. Louis suffered against the other League teams.53 Von der Ahe also couldn’t retain Comiskey, who signed a three-year agreement with the Cincinnati Reds for $20,000 and a share of the club’s profits. Von der Ahe offered Comiskey his old salary for one year which Comiskey refused.54

In the February 5, 1892 edition of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, statistician Clarence Dow, predicted that the Browns would finish last in the National League. “While it has some strong individual batters and fielders, it has a number of misfits,” Dow said.55 Two days later, Von der Ahe replied, “this same statistician put us in seventh place last year and had we not been thrown down by a trio of drunkards we would have won the pennant. … It would be well to bear in mind that paper teams seldom win pennants.”56

Von der Ahe’s eye for talent was not good. When a scout brought a young player to him, Von der Ahe turned the player away, saying “Dot little fellow … Take him over to the Fairgrounds and make a hoss yockey out of him.”57 The player was John McGraw. Without Comiskey to help him find talented players and keep them in line, Browns’ fans were the ones to suffer as they watched their team finish in 11th place.

The National League adopted a split season in 1892, seeking to give fans hope in cities that had done poorly in the first. Before the second half began, the League’s owners enacted a resolution to cut player salaries 20 percent, blaming poor attendance in most of the cities. Von der Ahe used this as an opportunity to cut salaries five to 15 percent but retroactive to the start of the season, meaning his players suffered a salary reduction of 10 to 30 percent. 58

Comiskey criticized Von der Ahe’s micro-managing. “You have a strong team at every point … in Jack Glasscock you have a first-class man. But he is not going to be successful … to the interference of President Von der Ahe … coming down from his private box. … The aggregation of players was on pins and needles while Mr. Von der Ahe was on the bench. In their anxiety to show up well they became nervous. The old players understood this and didn’t mind it. For new players, they aren’t used to it. … Chris himself will be the biggest sufferer. … If the present state of affairs continues … the sport will be dead in this greatest of baseball towns.”59

Over time Comiskey would be proved half-right.

On April 27, 1893, the Browns and Chris Von der Ahe opened New Sportsman’s Park.60 It was located at Natural Bridge Road and Vandeventer Avenue, not far from the old park and the Fairgrounds. Von der Ahe said the new park was built because he was concerned the increasing value of the Grand Avenue Grounds park would lead the owners to sell it. Von der Ahe signed a 15-year lease for the new site. It would save him $3,000 per year and gave him the right to make improvements as needed.61 Plans for a cafe, restaurant and saloon were on the drawing board. Street car lines ran directly to the grounds with another loop built around it.

Designed by Architect August Beinke, of Beinke and Wells, the grandstand measured 164 feet long and 60 feet wide. The pavilions were of equal width, 100 feet long, and the grandstand was 65 feet tall up to the press box. Iron columns and trusses supported the peaked roof, with the front columns set back to provide an fewer obstructed views of the field. Opera chairs were used in the grandstand and put on platforms to provide better views.

On the north and south ends of the grandstands were private boxes running 25 feet back from the front. The ballpark also had a bicycle path which encircled the park with a quarter-mile track and a one hundred yard sprinting stretch along the north side of the park. The baseball diamond was laid out by Augustus Solari and the infield contained Kentucky bluegrass, with the players locker rooms located on the first base side of the field. There was large open space at ground level with a barroom which could hold 1,600 patrons, and was the only place to sell liquor in the park.62 The cost of the wooden structure was $50,000.63 Capacity was 14,500.64 Home plate was laid with a buried time capsule of newspaper articles and mementos of the Browns’ pennant years and World Championship.65

Despite playing in a new ballpark, the large uptick in attendance that Von der Ahe hoped for didn’t occur. It was only 1.3 percent. Von der Ahe, still wanting to maintain his free-spending lifestyle, took on more financial risks. He tried using New Sportsman’s Park for other events, but they weren’t profitable. In one case, he was sued for not paying performers in a Civil War reenactment that he brought into the ballpark during the summer. He lost that suit and had the added expense of repairing the playing field torn up during the reenactment.66 He also lost money on a Wild West Show. Von der Ahe lost the suit because it was proved he had assumed all the show’s expenses when he purchased the show at auction.67

As these financial failures mounted, Von der Ahe traded or sold his better players. He also got involved in a costly, and revealing, lawsuit with his son. The suit was over who had ownership of properties the elder Von der Ahe had used to secure loans totaling $21,700.68 In the course of his testimony, the younger Von der Ahe described his father’s lifestyle as extravagant, citing $4,000 spent on a trip. He said his father used the club’s treasury for financing non-team projects and he didn’t account for the money or pay it back. His father was also in debt to Northwestern Savings Bank for $44,000 and the property to secure the loan had a value of $16,000.69 The ballpark and club were only insured for $20,000.70

Members of the Fourth Estate didn’t hide their distaste for the way Von der Ahe ran the club, saying he lost his nerve when negotiating with the National League for membership in 1892. “The career of the St. Louis Club as a member of the 12-team League has been marked by reverses during every season. It has never held a respectable position after the second month of play. St. Louisans have been loyal to the club in its adversity in the hope that the man who downed the League would show some of his former energy and liberality in building up the team.”71 In conclusion Von der Ahe had been more interested in 25-cent admissions, Sunday games and beer than in protecting the playing quality of his team.

Von der Ahe thought the criticism was unfair, but he was undeterred. He said he was staying in baseball and would not selling his best player, pitcher Theodore Breitenstein. If and when he did sell the Browns, his asking price would be $100,000.72 He continued to pursue other financial ventures. At the New Sportsman’s Park he built a race track and a “shoot the chutes” ride where flat-bottomed boats slid down a water ramp into an artificial lagoon. The race track made his fellow National League owners uneasy because of the gambling connection.73 These ventures were financed in part with $23,000 in loans to the Sportsman’s Park and Club from friend Edward C. Becker, a retired grocer, investor, venture capitalist, and Von der Ahe’s “guardian angel.”74

Sensing that he was about to be ostracized by National League owners for his operation of the Browns plus his other endeavors involving New Sportsman’s Park Von der Ahe skipped the League meeting in New York in February 1896. To avoid a volatile confrontation, he sent his lawyer Walter Hetzel instead. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported “the National League has become indignant with the way Von der Ahe has operated the team. League magnates have a growing understanding that St. Louis fans are hoping that the baseball team can be taken from Von der Ahe or it will soon become a part of St. Louis baseball history.” The paper predicted that if the League took the franchise from Von der Ahe, it would have the “hearty good will and cooperation of the better element in the city. The League owes it to itself and to St. Louis, one of the best baseball towns in the country to allow it to attend games on a proper basis and not under the conditions Von der Ahe has dictated.”75

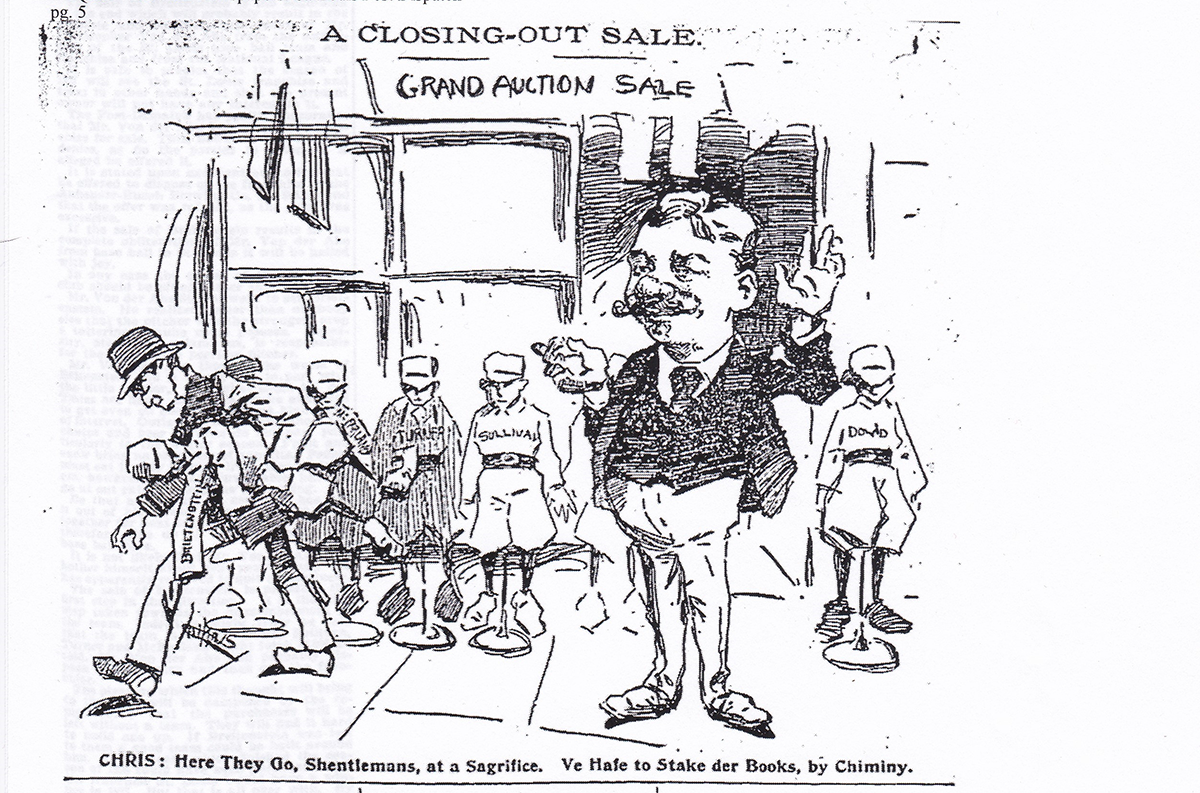

The cartoon above from the St. Louis Post Dispatch clearly illustrated that Von der Ahe’s desire for cash at the expense of putting a competitive team on the field outweighed ostracizing by League owners, condemnation by a certain local newspaper and an angry fan base. He was not afraid to sell any player, including Breitenstein, the St. Louis-born pitcher who was arguably his best player and main gate attraction. Breitenstein went to Cincinnati for $10,000.76 The Post-Dispatch said the trade not only dimmed the hopes for 1897, but reduced the value of the club if Von der Ahe decided to sell. The paper estimated Von der Ahe could get no more than $50,000 for the team.77 It reported rumors he had approached the Anheuser-Busch Brewing Co. to take the Browns off his hands for $65,000, but had been turned down.78

Despite the cash influx, Von der Ahe was facing further debt woes. On February 21, 1897, the New Sportsman’s Park’s roof caught fire and spread to the stables, where 150 horses were kept. None of the horses perished. The fire also damaged the boarding houses and Von der Ahe’s “Shoot the Chutes.” Von der Ahe had let the insurance on the buildings and track expire. He had only recently sent in the renewal but hadn’t received a reply from the insurance company that there was a policy in force. As a result he feared there would be trouble collecting insurance for the fire damage. Von der Ahe’s secretary, B.S. Muckenfuss, told a St. Louis Post Dispatch reporter, that the cost of the damage would be $2,500.79

Creditors were taking action against Von der Ahe and the Sportsman’s Park Club and Association. In one instance, Aetna Iron Works, a company that manufactured architectural, ornamental and structural iron, won a court judgment.80 The sheriff set an auction for some of the Sportsman’s Park and Club property.81

Von der Ahe knew creditors would get virtually all the assets if he sold the club, so he decided to restructure the Sportsman’s Park Club and Association (SPCA), making himself a preferred creditor.82 On January 12, 1898, through a deed of trust, Muckenfuss was named president and J.W. Peckington secretary of SPCA.83 Von der Ahe’s claims against the organization totaled $108,962.There were 28 other creditors with unsecured claims between $125 and $3,925 and an additional dozen with unsecured claims between $7 and $90.84

But the deed of trust did not supersede mortgages held on the ballpark, other judgements held against the association, Edward Becker’s note for $23,000 and $20,000 in bonds. Under terms of the lien for Aetna Iron Works judgment, Von der Ahe had to sell the Browns and the organization’s property within six months.85

Just three months after the deed of trust reorganization, another fire struck New Sportsman’s Park. The fire started as flames from the restaurant kitchen set several large awnings stored under the pavilion ablaze. It took only 28 minutes for the grandstand, pavilion, and the 300-foot bleachers.86 The losses were $60,000 but the ballpark was insured for only $34,600.87 Von der Ahe lost valuables and personal papers totaling about $30,000. Fans entering the ballpark for the next day’s game saw crews working around the clock to get temporary seating finished.88 Von der Ahe said a new grandstand with easy access in and out was going to replace the burned one, but because of the high cost of iron, it would be made of wood.89

In July, Von der Ahe finally thought he had a buyer for the Browns when Edward C. Becker, friend and “guardian angel” agreed to pay $50,000 for it. There had been no takers for the team other than Becker, who was Von der Ahe’s last hope as he pressed against the deadline of the Sheriff’s auction. Immediately there were rumors flying about what players Becker would obtain for the Browns.90

However, after buying the Browns, Edward Becker changed his mind and called off the purchase. This was despite the creditors being satisfied and the transfer papers agreed upon plus other issues being resolved. It was rumored that Cleveland owner Frank De Hass Robison wanted to buy the St. Louis franchise and move it to Cleveland while placing the more successful Cleveland club in St. Louis, where Robison thought the St. Louis fan base would be more supportive.91 John D. Johnson, the broker of the sale with Becker, was angry Becker had left Von der Ahe hanging. He said it had been Von der Ahe’s last chance to sell the club through private channels rather than the sheriff’s auction. He also surmised that Becker changed his mind because he felt that he would have gotten a better deal at a public sale. Johnson said he was going to head East to round up capital to purchase the club. This possibility allowed Von der Ahe to win an additional six-month delay in the sheriff’s sale.92

The axe fell on Chris Von der Ahe on January 5, 1899 when the Mississippi Valley Trust Company foreclosed on Von der Ahe and the Sportsman’s Park and Club Association’s mortgage.93 Von der Ahe tried to argue that the Browns franchise was not secured by the mortgage.94 On January 23, the judge ruled against Von der Ahe and reinstated the Sheriff’s auction.95 An appeal was overruled on February 6.96

Before the auction, the National League owners took steps to give Frank De Hass Robison clear title to the Browns National League membership. They voided the Browns’ league membership because of its failure to pay League dues plus unpaid player-transaction fees. The League then allowed Robison to pay the Browns’ league dues and debts to reestablish the Browns’ membership.97

The machinations didn’t work, at least at first. When the March 14 auction ended, the club had been bought by G.A. Gruner, treasurer of the Phil Gruner & Bros. Lumber Company, for $33,000. Gruner was representing the creditors group and said the team would be run in their interest.98 Three days later, Gruner changed his mind. The latest buyer was Von der Ahe’s old and erratic supporter, Edward Becker, who paid $35,000 for the team and the ballpark.99 A week later, the worst kept secret in St. Louis was confirmed. Robison paid Becker $40,000 for the Browns, the lease, the ballpark and other property and proceeded with his plan to move the Cleveland players to St. Louis.100 Later, it would become clear that the deal only brought Robison 400 shares in the team, while Becker retained the other 600.101

For St. Louis fans, the Cleveland players coming to St. Louis would give them a chance to watch the kind of competitive winning team they had been pining for since the days of Comiskey and the American Association.102

The Robison Brothers

St. Louis Perfectos (National League), 1899

St. Louis Cardinals (National League), 1900-1911

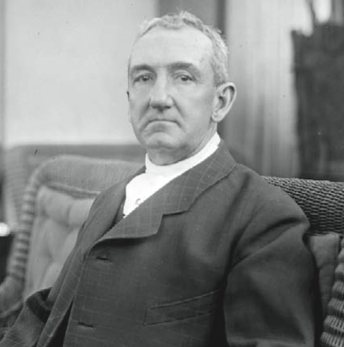

Frank De Hass Robison was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1852, the son of Martin Stanford Robison and Mariah (Allison). He spent his boyhood in Dubuque, Iowa. He married Sarah Carver Hathaway, of Philadelphia in 1875 and they had a daughter with the given name Helene Hathaway. He attended Delaware University for a short time.

Frank De Hass Robison was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1852, the son of Martin Stanford Robison and Mariah (Allison). He spent his boyhood in Dubuque, Iowa. He married Sarah Carver Hathaway, of Philadelphia in 1875 and they had a daughter with the given name Helene Hathaway. He attended Delaware University for a short time.

Robison and his father-in-law, Charles Hathaway, started Hathaway & Robison to build and operate streetcar systems. The business was headquartered in Cleveland, but built systems around the United States and Canada. In 1889, Robison personally undertook the formation of the Cleveland Railway Co. and constructed 26 miles of lines. Four years later, Robison merged his company with Marcus A. Hanna’s Woodland and West Side Railway to form Cleveland City Railway.103 However Robison lost one million dollars in the merger when his broker fraudulently sold the stock to Hanna and kept the proceeds. Robison sued Hanna but it would take ten years before he won a financial judgement and was awarded a fraction of his losses.104

Robison entered professional baseball in 1887 when he organized the Cleveland Blues of the American Association. Two years later, the team moved to the National League and was renamed the Cleveland Spiders. Robison built League Park on his cable car line which allowed both increased ridership on the trolleys and greater attendance at the ball games.105 Despite success on the field with a team that included Cy Young, Bobby Wallace, and Jesse Burkett, finishing in the first division of the National League from 1892 through 1898, and beating the Baltimore Orioles in the 1895 Temple Cup series, attendance was sporadic.

Frank Robison left the Spiders in the hands of his younger brother. Martin Stanford Robison, and named after his father, was born March 30, 1854 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He was generally known as Stanley. He never married.106

For his first season of ownership in St. Louis, Robison had contractors get the ballpark ready for the “new” St. Louis Browns. The field was manicured to look better than it had been under Von der Ahe’s ownership. There was a complete makeover of the grandstand and new bleachers replaced the old.107 The capacity of the ballpark at Vandeventer and Natural Bridge Avenues increased to 15,200.108 In another change from the Von der Ahe regime, New Sportsman’s Park was renamed League Park.109

On April 15, 1899, when Robison’s St. Louis team took the field for Opening Day, they were not wearing brown but a different primary color. “The Clevelands … had on their white stockings and gray trousers, A Dingy Effect Contrasted With The New White Suits and Cardinal Stockings And Caps For The New St. Louis Team,” the Post-Dispatch reported.110

Robison didn’t give his team a nickname but the sports writers of the day did. On May 13, 1899 the Post-Dispatch called Robison’s team the “Perfectos.”111 The nickname “Cardinals” appeared nearly a year later in the April 3, 1900 edition of the St. Louis Republic.112 But other nicknames, such as the “Red Caps,” continued to appear.113

Official credit for coining the “Cardinals” nickname was awarded to the Republic’ s reporter, Willie McHale. According to a John Wray column in the October 5, 1931, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Willie’s brother, P.J., told the following story: “A Chicago girl named them during the middle of the season….when the St. Louis team came out on the field, road gray uniforms, bright red trim walking across the field was a pretty picture. Nor did the picture escape the eyes of the Chicago Miss who clapped her hands enthusiastically and exclaimed to her companion, ‘Oh, isn’t that a lovely shade of cardinal.’ McHale caught the explanation and a moment later had flashed over the telegraph wires to St. Louis in his introduction of the game that “The Cardinals” were confident of victory.”114

Regardless of the nickname Robison’s 1899 team had a successful season at the gate — 373,909 fans — setting a franchise record. When the National League got rid of the joint ownership rule in 1900, it folded the Cleveland team and Stanley joined his brother in St. Louis. The brothers Robison eyed adding players from Cleveland and the three other teams the National League had axed after the season.

Regardless of the nickname Robison’s 1899 team had a successful season at the gate — 373,909 fans — setting a franchise record. When the National League got rid of the joint ownership rule in 1900, it folded the Cleveland team and Stanley joined his brother in St. Louis. The brothers Robison eyed adding players from Cleveland and the three other teams the National League had axed after the season.

Robison was not shy in his interest in obtaining John McGraw to add to his “stable of stars” which included Cy Young, Bobby Wallace, Jesse Burkett and Emmet Heidrick. Since Baltimore was no longer a member of the National League, McGraw and his teammates Wilbert Robinson and Bill Keister had been assigned to Ned Hanlon’s Brooklyn Superbas. Brooklyn and Baltimore had had a joint ownership arrangement like the Cleveland-St. Louis combination.

After the League meetings Robison approached Hanlon about obtaining McGraw and Robinson. During the course of negotiations, it was revealed that McGraw was trying to get Baltimore into a revived American Association as he had the lease rights to the Baltimore playing field. He said he would only to return to the National League for a $5,000 salary. His buddy Robinson would have to be signed as well and paid $3,500. McGraw also demanded $3,500 of the purchase price if Brooklyn sold his rights and Robinson $500 if his rights were sold.115 On March 10, 1900, Robison obtained the rights to McGraw, Robinson and Keister by paying Brooklyn $19,000.

Negotiations between Robison and McGraw were contentious. McGraw said he didn’t want to play in St. Louis and said Robison would blacklist him if he didn’t. However, Robison saw McGraw as someone to build the St. Louis team around and wanted him to manage it.116 Robison and McGraw agreed to a $100 per game salary with free agency at the end of the season. Wilbert Robinson received a salary of $3,500 and a $2,500 bonus and also would not be reserved. In addition, Robison had to pay $500 to the bartender who ran McGraw and Robinson’s establishment in Baltimore while they were away playing for St. Louis.117

McGraw and Robinson did not see any game action until May 12, 1900, the Cardinals’ seventeenth game, citing personal business in Baltimore.118 By the time they did play, the Robisons were feeling the pain of a street car strike that had started May 8. The violent nature of the protesters and workers was making fans leery of going to League Park.119

Robison didn’t get a great return from McGraw and Robinson. Although there were other factors that resulted in the Cardinals’ falling far short of the pennant, it was the contentious dealings with McGraw that stuck in Robison’s craw. Insult was added to injury when McGraw refused to take over as manager when Patsy Tebeau resigned in August, saying it was unfair to him to take over with the team in seventh place. McGraw also disagreed with Tebeau’s replacement, Louis Heilbrunner, who wanted McGraw to be the player-manager, making roster moves during games and levying fines as needed. McGraw wouldn’t do that, saying it wasn’t his responsibility.120 Robison found out it was McGraw’s way or no way and realized he had paid a heavy financial price shelling out $35,300 to obtain him.

After the season, it was reported by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that Robison had failed to pay some of the players their remaining salaries by the deadline of October 19, five days after the season ended. As a result, the players who had been reserved on September 30 — Heidrick, Mike Donlin, Burkett, Cowboy Jones, Jack Powell, and Wallace — were now free agents.121 They could sign with any National League team or a team in the new American League.122

In addition to McGraw and Robinson, who were free agents because of their 1900 contract terms, Robison lost Cy Young and Mike Donlin to the American League. Robison was able to re-sign three of his best players — Jesse Burkett, Bobby Wallace and Emmet Heidrick. He purchased Patsy Donovan to manage and play outfield.

To get the money to sign these players, Frank Robison borrowed $18,500 from his brother Stanley to be paid back in 60 days.123 The loan was secured with 185 shares of Cardinals stock.

Robison failed to pay back the loan and Stanley announced the 185 shares had been transferred to him.124 That started a rumor in Chicago that foreclosure on the Cardinals was imminent and potential suitors were coming forward to make offers for the franchise.125

Despite the rumors, the Robison brothers still held on to the Cardinals. “Everything was lovely” between Becker (600 shares), Frank (215 shares) and himself (185 shares), said Stanley Robison. He also downplayed the foreclosure and sale rumors by saying, “it was merely a business transaction and the stockholders of the club are the only parties interested in it.126

On May 4, 1901, League Park caught on fire and caused more financial headaches for Robison. Despite the panic from 3,000 fans in attendance, there were no injuries as Cincinnati and St. Louis players responded by calmly directing fans away from the flames. The cause of the fire was a lighted cigarette carelessly dropped from one of the private boxes onto the wooden grandstand. Once the blaze was extinguished — after a futile attempt with a non-working fire hose — the damage was $30,000. The Robisons did not have full insurance coverage.127

Robison’s insurance claim took almost two years to settle as it required a court judgment. The $20,000 that was received did not cover the damage.128 The last game of the homestand was played the next day at Athletic Park, despite having a bicycle course and not being suited for baseball.129

Since the ballpark at Vandeventer and Natural Bridge had suffered three fires in five years, the City of St. Louis building commissioner wanted it rebuilt with concrete and steel and denied the Robisons a building permit to use wood. But a steel and concrete facility needed more time to be constructed and wouldn’t be finished before the Cardinals returned home in three weeks.130 Robison circumvented the building commissioner by taking the plans for a wood structure to the St. Louis mayor and then to the city’s board of appeals. He got his building permit. The new wooden grandstand was to be built with the fans closer to the ground and more exits than before.131

The financial losses in 1900 and the out of pocket expenses to rebuild League Park put Robison behind the eight ball in trying to keep his best players from jumping to the Cardinals new cross-town rivals, the American League Browns. American League president Ban Johnson wanted to compete directly with National League reams and moved his Milwaukee team to St. Louis for the 1902 season. Robert Hedges of the Browns was wooing Burkett, Wallace, Heidrick, Powell, Harper, and Padden.132 Veteran pitcher Willie Sudhoff said he was dissatisfied with Robison’s salary offer and would jump the Cardinals for a better one.133 Rumors were circulating that Hedges was willing to pay Wallace $6,000, Burkett $5,000 and Heidrick $4,000 and that those amounts were too rich for Robison to pay.134 When the 1902 season opened, the Cardinals had lost all seven players to the Browns. In addition, first baseman Dan McGann jumped to Baltimore.

Robison sought an injunction to keep the players from jumping to the Browns. He argued the jumpers were still under contract to the Cardinals. He said Wallace and Heidrick were in the second year of multi-year contracts, and Harper had signed a contract for 1902 in August of 1901.135 On May 6, 1902, St. Louis Circuit Court Judge John Talty rendered a permanent denial of Robison’s injunction request against Harper and Wallace saying that Robison failed to prove that Harper had a set of unique talents versus other ballplayers, and that Harper’s and Wallace’s contracts were written to favor Robison, restricted their personal liberty and violated the current anti-trust laws. In a separate action, Circuit Judge Daniel Fisher dismissed Robison’s injunction request against Heidrick in an oral decision.136

The Browns outperformed the Cardinals in both the standings and attendance in 1902. Hedges challenged Robison to a postseason “City Series,” with the winner receiving a trophy worth $2,500. Robison, still smarting over the losses in court, standings and attendance, didn’t accept the challenge.137 Robison changed his mind during the off-season and came to an agreement with Hedges to hold “City Series” games starting before the 1903 regular season started.138

In early 1903, Robison finally received his damage settlement from Mark Hanna and Little Consolidated Railway Co. of Cleveland after years of negotiations and court appeals. The award of $175,000 was a fraction of the $1 million embezzled from Robison ten years ago.139

Robison used part of the settlement to buy Edward C. Becker’s 600 shares in the Cardinals. With the purchase, Frank Robison had controlling interest in the Cardinals with 815 shares. Stanley Robison still held 185 shares.140

Despite his majority of the shares, Frank Robison became less and less involved with the management of the Cardinals. He was in Cleveland to take care of his ill wife. The reduced settlement with Mark Hanna, losses suffered in operating the Cardinals and the League Park fire left him in financial straits. To regain financial solvency, Robison quietly, and over the next few years, sold shares in the Cardinals to his brother, ending up the minority shareholder. In public, he told everyone that he still was the largest shareholder of the Cardinals and the decision maker. Eventually, that got Stanley’s goat and their relationship suffered. On August 27, 1906, Stanley announced he was the president of the Cardinals with total control.141

Stanley Robison had worn many hats for the Cardinals — treasurer, vice-president and even field manager. So he knew his way around a clubhouse and offices. He knew what it took to make the fans come to the ballpark. On July 7, 1901, when he was the Cardinal treasurer, he wrote an opinion piece that allowing men to watch the game in their shirtsleeves would boost game attendance. He gave the example that 21,000 men who attended the July 4 morning and afternoon doubleheader, were not wearing their coats because of the oppressive heat and were seen in shirts and shirt waists. Stanley said he would prefer men go coatless and unbutton their collars and shirtwaists on hot days rather than to risk the loss of attendance by 25 to 50 percent.142

Attendance was an abiding concern for Stanley Robison but he knew trailing the Browns in attendance was caused by on-the-field performance. Before the 1909 season, Stanley sent an SOS to John McGraw knowing the Giants’ manager was looking to improve his pitching staff.143 Pitcher “Bugs” Raymond, outfielder Red Murray and catcher Admiral Schlei were sent to McGraw for Hall of Famer Roger Bresnahan.

The catcher was made the player-manager and centerpiece of the team as Stanley signed him to a three year $25,000 contract.144 Eventually, he insured him for $50,000.145 With Stanley’s declining health, Bresnahan was given total responsibility for the operation of the Cardinals.146 One of Bresnahan’s first decisions was to cancel the “City Series” to better prepare his players for the full season. Despite the potential revenue loss of $15,000, the Cardinals owner agreed. “It isn’t that I am trying to get back at Mr. Hedges for calling off the fall series. Mr. Bresnahan thinks it’s best to give all the time in preparing the team for the opening of the regular season. He doesn’t want to have anyone in bad shape and as we are starting a new era. … I think it best to give Mr. Bresnahan all the chance in the world to have the club ready at the start.”147

Expecting more fans to come through the turnstiles, Robison upgraded League Park with a larger grandstand, opera chairs, and “monster” bleachers in right field. The seating capacity of the park was increased to over 20,000.”148 In his first two years, Bresnahan helped Robison and the Cardinals make money. The franchise made $40,000, in 1909 and $60,000 in 1910 despite finishing seventh both years.149

Things took a tragic turn for the Cardinals’ franchise when on March 24, 1911, at his sister-in-law’s house in Cleveland, Stanley Robison passed away. The cause of death was reported as a stroke. Robison had been ill for two years.150

In his will, Stanley Robison left the Cardinals to Frank Robison’s wife and daughter. Garry Herrmann, chairman of the National Commission, baseball’s ruling body, quickly made the announcement that despite the will, the team would not be owned or controlled by a woman. He assumed the Robison women would sell the team. Respecting the grieving process, Herrmann stated that the decision would not be made immediately.151 Herrmann would be proven wrong on several counts, mostly because the niece, Helene Robison Britton, wanted to be involved.

Helene Hathaway Robison Britton

St. Louis Cardinals (National League), 1911-1916

Helene Hathaway Robison Britton was born January 30, 1879 to Frank De Hass Robison and Sarah Carver Hathaway Robison in Cleveland Ohio. Helene at an early age became immersed in baseball. She traveled with her father’s team on road trips and was their mascot at the games.

Helene Hathaway Robison Britton was born January 30, 1879 to Frank De Hass Robison and Sarah Carver Hathaway Robison in Cleveland Ohio. Helene at an early age became immersed in baseball. She traveled with her father’s team on road trips and was their mascot at the games.

Baseball dictated her life so much that she scheduled her wedding to Schuyler Britton, a member of Cleveland’s upper crust, after the 1901 season to ensure her father could escort her down the aisle. The Brittons made their residence in Cleveland. They had two children, Frank De Hass (1903) and Marie (1907).152

On the day her uncle died, Helene Britton sent a telegram to Garry Herrmann telling him that “Uncle Stanley had passed” and asking him “Will You Please Be A Pall Bearer?”153 Four days after the funeral, the New York Times ran a story about Herrmann’s change of heart towards Britton’s owning the Cardinals. Herrmann said that Britton would not be prevented from owning the team, but that it would be up to Britton to have a male be her proxy at League meetings.154

The will provided that the stock in the American Baseball and Athletic Exhibition Company of St. Louis, Missouri (the Cardinals corporate name) be divided between Helene Britton and her mother, Sarah Carver Hathaway Robison. Helene Britton would get three quarters of the shares. It also provided that Helen’s children would inherit ownership of the Cardinals upon the death of their mother and grandmother.155

The same day President Herrmann made his announcement, Charles Weeghman, a Chicago restaurateur, offered her $350,000 for the ball club, League Park and the surrounding grounds.156 Three days later another offer was received from James McGill, president of the Denver Club in the Western League.157

But Helene Britton had no intention of selling the Cardinals and she made that crystal clear in a joint statement with her husband Schuyler on April 6, 1911. Speaking for his wife, Schuyler said, “The St. Louis National League Ball Club is not for sale. Britton has decided to retain the ball club. … She has received numerous offers for the property but all were turned down. The baseball property is not for sale at least for the time being.” As her husband read the statement, Britton nodded her head in agreement, and the Cardinals remained the family business.158

Like her father and uncle, Helene Britton would not move to St. Louis.159 She maintained her residence in Cleveland with her mother and traveled to St. Louis as necessary for meetings and ball games such as Opening Day.160

During her first week as an absentee owner, she delegated the off-the-field operations of the Cardinals to Herman D. Seekamp. He served as temporary club president overseeing the operation of the Cardinals and being their liaison with the National League until the Cardinals; board of directors could convene.161

At that meeting of April 6, 1911, chaired by Britton, she announced that Ed A. Steininger, whom she knew through his friendship with her uncle, would be the president of the Cardinals. Steininger had a contracting business that did most of the work at League Park. He announced that he was a fan only and all baseball-related transactions on and off the field would be the responsibility of manager Roger Bresnahan. He also announced that building new stands at League Park would be dealt with at a later date as other matters took priority.162

Being the first woman owner in baseball, Helene Britton made news not only in the sports pages. Two weeks after becoming the owner and confirming she would not sell, St. Louis Post-Dispatch society page columnist and sketch artist Marguerite Martyn published an interview with Britton. “The interest in baseball among women is growing steadily. Why shouldn’t the superiority of our national game over the sports peculiar to other nations be recognized and encouraged by women? They owe it to the men, their sons and husbands, to encourage them in a diversion so healthy, so clean, so stimulating to the heroic in their natures. It won’t do women any harm, either, to cultivate in their own ideas of masculinity, all those really manly qualities … which are brought to the fore in baseball. On the other hand, women’s presence at the game, as elsewhere, will have the desired civilizing effort,” Britton said.

She noted her uncle had removed the park bar, a money-maker, “to make the grandstand more pleasant and attractive to women fans.”163

After meeting with president Steininger and manager Bresnahan, Britton did two things to increase the attendance of women at League Park. The first was to sell tickets at a drug store located in the city’s business district. She felt that it would be a safer venue to buy tickets instead of venturing into a saloon.164 The second was instituting “Ladies” Day on April 15, 1912. All ladies with a male escort would be admitted to the grandstand free. Under her uncle’s ownership, tickets for women had been 25 cents less than the regular admission fee.165

Britton’s first year as owner was an eventful one, on and off the field. The Cardinals had their best record since 1901 when her father was president, drew a franchise high in attendance as a National League team, and made a profit of $127,000.166 Just as her father had endured a near tragedy with the League Park fire in 1901, she had to endure a near tragedy when the team survived a horrific train wreck on the morning of July 11. The train had been delayed a couple of times by Bresnahan’s demand that the Cardinals sleeper cars be moved from behind the engine. That decision saved their lives as the cars that replaced them endured the brunt of the wreck, which killed 12, including the engineer, and injured 47. The Cardinal players assisted in finding the injured and those that died. They were hailed as heroes but to a man they didn’t feel like heroes.167

League Park was renamed Robison Field for her father and uncle that same year. In appreciation for the team’s finish and optimistic prospects for the future, Britton gave Roger Bresnahan a five-year contract extension which also gave the Cardinal manager a percentage of the profits.168

On December 12, 1911, at the Waldorf Hotel in New York, Britton became the first woman to attend a National League meeting.169 She was accompanied by Steininger, who was her proxy. She witnessed Steininger cast her vote which reelected incumbent National League president Thomas Lynch.170

She wasn’t intimidated in the owners’ presence and she brought order and manners to the meeting, something that had never occurred, the New York Times reported. The League owners deferred to her and refrained from smoking cigars during the meeting. She said she wasn’t bothered by it as her father and uncle smoked, so she told the other owners they could smoke if they wished, and they didn’t waste the opportunity to smoke, puffing away as usual.171

She took her place with the rest of National League magnates when a group photo was taken December 12, 1911 at the Waldorf Hotel.

But things still didn’t go smoothly with her male colleagues in St. Louis. In April 1912, Britton and her mother obtained an injunction to stop Steininger from using his proxy at the board of directors meeting. They said he wouldn’t vote according to their wishes and she felt Steininger had shown a lack of transparency.172 There was inadequate information regarding the expenditures, revenues and dividend payments of the Cardinals and the financial information was locked in a safe to which she had no access.173 The court ruled in favor of the women.174

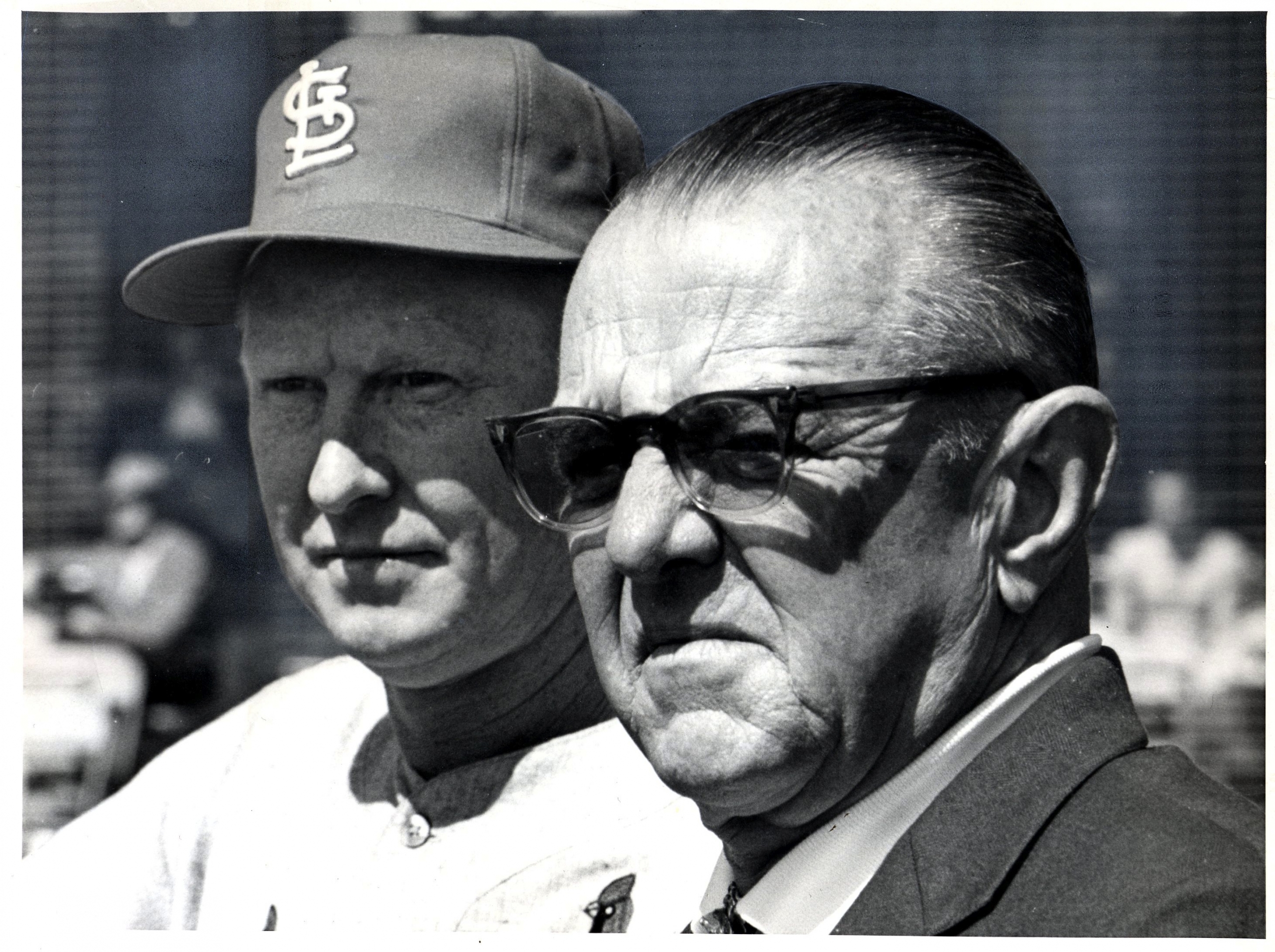

St. Louis Cardinals owner Helene Britton, top center, poses with other National League team owners at the winter meetings in 1913. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Steininger wasn’t the only Cardinal official to feel Britton’s ire. The good feelings between Bresnahan and Britton began evaporating in 1912. It started when the Cardinals’ manager didn’t notify her about the change in training camp from Jackson, Tennessee, where it was raining and made field conditions unplayable to Jackson, Mississippi. When Britton asked Bresnahan why he had switched camps, he was so disgusted with her demands for an explanation that he didn’t tell her it was for the players’ benefit.175

Things got worse when Britton told Bresnahan that any trade had to be cleared first with the new president James C. Jones, an insurance attorney who replaced Steininger. Jones was very tight-lipped about giving information about his role in the front office.176 As a result, no major trade occurred during the season. The breaking point for Bresnahan came August 15 when the Post-Dispatch reported Britton had revoked a trade that would have sent Miller Huggins and George Ellis to Cincinnati for outfielder Mike Mitchell and outfielder Charles (“Tex”) McDonald. Bresnahan felt that Huggins had slowed down and with Lee Magee playing well at second he could get Mitchell, a top outfielder who he liked. Britton nixed the deal because she liked Huggins and thought he had the makeup of a good on-the-field leader. Bresnahan said he would not make any more deals to improve the club, since they wouldn’t get approved anyway.177

Bresnahan’s profit-sharing clause hamstrung Britton’s operation of the Cardinals office staff. The clause stipulated a cap of $10,000 total in salaries for the president, secretary, treasurer, groundskeeper, press agent and attorneys. Britton could not spend more until Bresnahan got his 10 percent of the net profits. But attorneys’ fees alone exceeded $10,000.178 Knowing that Bresnahan’s contract was hurting the team, Britton fired Bresnahan and hired Huggins.179 The move was expected to save Britton $8,000 a season with Huggins getting paid $6,000.180 The remaining years of Bresnahan’s contract were settled for $11,500 each, and the Cardinals paid that in January 1913.181

Britton had a somewhat troubled marriage but reconciled with her husband in August 1911.182 A year and a half later she felt that it was necessary to get Schuyler involved in running the Cardinals, and in February 1913 she announced that Schuyler was the new Cardinals’ president. replacing Jones.183 The Post-Dispatch reported Schuyler had learned how to run a baseball franchise in a story headlined “He Has Been Groomed to Head the Cardinals.”184

The big question the Brittons faced was when wooden Robison Field would be replaced with a concrete and steel park. Schuyler made an announcement in July 1913 that construction on a new concrete grandstand would start in two months. The October home series against Cincinnati would be moved to the Reds park and the fall City Series games versus the Browns would all be played at Sportsman’s Park. Plans called for a single-deck grandstand to be constructed first with a second deck added when the Cardinals won a pennant.185 With the season’s average game attendance falling to 2,750, those plans were shelved and the Cardinals continued to play their games at Robison Field. It was estimated a new ballpark would cost the Cardinals $150,000. The idea was broached that a lease to play at Sportsman’s Park would cost less and it was available for half the season when the Browns were on the road, but for the moment that idea went nowhere.186

The inability to draw fans to a substandard Robison Field grew worse when the upstart Federal League started play in 1914 with a team in St. Louis. A brand new stadium was built for the Terriers, called Handlan’s Park, located at Grand and Laclede Avenues.187 Curiosity was so high that when the City Series game was rained out, St. Louis fans flocked to the new ballpark for an open house.188

The Terriers opened their season on April 16, 1914 in front of 20,000 fans at Handlan’s Park. The Cardinals had opened two days before only 3,000 fans at Robison Field.189 Handlan’s advantages were its downtown location with good access for residents on the south side of the city.190

Trying to keep the Cardinals competitive in a city that now had three major league teams, the Brittons opened up the purse strings for 1914. The team’s three best players, Magee, Pol Perritt and Ivey Wingo, collectively doubled their salaries to prevent them from jumping.

It didn’t work. It was the Cardinals’ best finish as a National League team, but didn’t come close to what they had drawn with Bresnahan as player manager in 1911. With lower revenues, higher salaries and its two competitors in more attractive ballparks, the Brittons began to discuss selling the team.191

The Brittons’ Robison Field problems kept getting worse. A March 1915 citation from the St. Louis City Building Commissioner in March 1915 specified that the bleachers at Robison Field were unsafe and must be repaired before games could be played there.192 As a result, all the games spring City Series with the Browns were played at Sportsman’s Park. The Cardinals were racing the clock to complete the repairs but Schuyler Britton said he wasn’t worried because the club had sold only two tickets in advance and the bleachers would be ready for the home opener April 22.193

The Brittons had been discussing a move to Sportsman’s Park, but Schuyler Britton announced on April 9, 1915 that the Cardinals would play their entire 1915 home season at Robison Field. The lease to rent Sportsman’s Park from Robert Hedges, the Browns owner, would cost $12,000. But, according to Schuyler, it wasn’t about the rent, “I have made arrangements to rush the work on the stands, and we will have the ballpark looking fit by the time the club returns from the opening road trip. We received lengthy petitions from fans and the neighbors asking us to stay. I’m afraid our team would lose identity by going to the Browns’ park.”194

The Federal League situation in St. Louis was getting more complicated. Phil Ball, owner of the Federal League Terriers, met with American League President Ban Johnson to discuss buying the Browns, because Robert Hedges wanted to get out.195 Ball’s original plan to buy the Cardinals had been stymied by the Brittons’ insistence on keeping the team.196 Johnson sounded positive regarding his discussions with Ball.197

Schuyler Britton was adamant that he would sell the Cardinals for a profit and would not be pressured to sell. At the end of the 1915 season, executives from the three leagues got together to hammer out a plan for peace. The reports were that Ball would buy the Browns and the Cardinals would lease Sportsman’s Park from him for the 1916 season.198

On December 23, 1915, peace was achieved. Ball bought the Browns from Hedges, leaving the Cardinals in Helene Britton’s hands and still playing at Robison Field. Most Federal League players could be purchased at auction.199 Huggins wanted to purchase some Federal players to strengthen his talent-challenged club but Schuyler Britton refused to add payroll. He also considered the Federal League players jumpers or scabs.200 Schuyler’s obstinance would hamper the current team and future plans to sell the franchise.

Britton had two suitors for the Cardinals and Robison Field. The first was Henry Ford (Harry) Sinclair, Tulsa oil tycoon and one of the financial backers of the now defunct Federal League. Sinclair felt that the St Louis National League franchise played in an outdated ballpark and lacked talent. He offered $325,000 and walked away when Britton insisted on $425,000.201 The second was a syndicate from St. Louis represented by Henry Weisels, head of Weisels Gerhart Realty Co.202 The Weisels’ syndicate didn’t want to go any higher than $375,000.203 Schuyler Britton said he stopped negotiating with Weisels when he found out the real estate mogul only wanted to Robison Field to divide the property into lots to build bungalows.204 Weisels planned to play at Sportsman’s Park.205

A mystery buyer surfaced and quietly disappeard, discouraged by Schuyler’s take-it-or-leave-it pricing and inflated view of what the team was worth.206 Fans were getting frustrated with the uncertainty. Reporter J.V. Linck summed up that frustration with a rhyme in the February 15, 1916 St. Louis Globe-Democrat:

“We’d like to see the Cardinals change hands or else an end

Of stories of these pending deals which nothing do but pend;

If Britton’s going to sell we hope he will not long delay.

If not, we hope he’ll get a team which winning ball can play.207

The 1916 season came with the Cardinals still in Britton’s hands and went with no winning ballclub on the field and at the gate.

In November 1916 Helene Britton filed for divorce from Schuyler after five years of trying to keep the marriage intact. Her petition alleged that her husband was an alcoholic and when drunk would verbally abuse her, that he promoted a toxic environment at the house inviting friends that she considered uncivilized who were loud and vulgar and that he provided no financial support for the family, and instead wasted her family fortune.208 Her divorce from Schuyler was settled, February 12, 1917.209

On that day, Britton was elected president of the Cardinals, quashing the rumor that Browns’ executive Branch Rickey would be the next president and business manager of the club.210 She disparaged Schuyler Britton’s operation of the Cardinals, saying he prevented progress of the club, but didn’t elaborate.211 For her part, she said she would be taking “a very active interest” in running the ball club. Huggins would continue as manager but the roster would be upgraded. The club was not for sale.212

A week later, she returned to her theme. “There is no chance for Mr. Weeghman to buy Hornsby or Meadows or anybody else that will be of any assistance to Mr. Huggins in building up the Cardinals. I have been annoyed by such reports before, but I wish to take this occasion to deny for all time that we intend to dispose of any available assets for cash. We are ready, willing and eager to make a trade. … But no more sales, no more cash transactions.”213

That winter, the rundown Robison Field was the subject of a letter written by N. Hollander Hall, St. Louis’ 21st Ward alderman, to National League President John Tener. Hall asked Tener to work for a new ballpark whether or not Britton remained. He said Stanley Robison had new plans for a ballpark in 1906, but those plans had never been acted on. Robison Field, he said, was in as bad a shape as it had been under Von der Ahe and the residents of the ward deserved a facility that complimented the improvements made to their neighborhood. He implored Tener to act as the league had done when they removed Von der Ahe from ownership of the franchise.214

In a retort, Britton said that no improvements would be made to Robison Field as the club had finished last in attendance in the National League in 1916.215 As 1916 came to a close it became apparent that, contrary to her vow in November, Britton was listening to offers to sell the franchise. A team that was considered to be a “woodpile” and a ball park better suited for kindling, was still getting interested buyers as impending sale rumors ran rampant.216

Britton said her asking price for the Cardinals would be $500,000. This was despite Phil Ball paying $75,000 less for a better ball club and a ballpark with a concrete grandstand.217

Helene’s Britton’s efforts to sell the club were hampered by the threat of a strike by players belonging to the “Fraternity of Baseball Players.”218 The strike ultimately was canceled and the union broken by the National Commission.219 Finally with the United States heading into the World War and military conscription on the horizon, Britton would be hard pressed to get her asking price.220

On February 27, 1917, James C. Jones, former president of the Cardinals announced that he represented a group called “the Cardinal Idea” that had an option to purchase the team from Britton for $350,000.221

The “Cardinal Idea” Ownership

The St. Louis Cardinals (National League) 1917-1919 and Branch Rickey

The “Cardinal Idea” was fan ownership through the purchase of subscriptions. Each subscription would purchase a share of stock at $50.00 per share. Jones’s goal was to raise $500,000 through the sale of ten thousand shares. That money would be put towards the $350,000 purchase price of the ballclub and provide working capital to operate the Cardinals.222

The “Cardinal Idea” was fan ownership through the purchase of subscriptions. Each subscription would purchase a share of stock at $50.00 per share. Jones’s goal was to raise $500,000 through the sale of ten thousand shares. That money would be put towards the $350,000 purchase price of the ballclub and provide working capital to operate the Cardinals.222