San Diego Padres team ownership history

This article was written by John Bauer

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

The San Diego Padres celebrated their 50th season in Major League Baseball in 2019. (SAN DIEGO PADRES)

San Diego’s quest for major-league baseball began earnestly in the mid- to late 1950s, around the time California’s largest cities, Los Angeles and San Francisco, ascended to “the bigs.” Home of the Pacific Coast League Padres since 1936 and backed by local banker and businessman C. Arnholt Smith, San Diego looked for an opportunity to obtain major-league baseball. City leaders sent representatives to baseball business meetings in hopes of making connections and generating good will.

If anyone was positioned to deliver a big-league team for San Diego, it seemed destined to be Smith. Well-connected among business and political leaders — he was a close friend and adviser to Richard Nixon — Smith’s boosterism earned him the nickname “Mr. San Diego.” Described as always wearing “a smile, a suntan, Buster Brown shoes and a brown suit,”1 Smith had a diverse portfolio of business interests that appeared to provide ample means to acquire a team.2 In addition to owning the PCL Padres, he headed more substantial organizations such as the U.S. National Bank and the Westgate-California Tuna Packing Corporation, the latter a conglomerate with seafood, ground transport, aviation, hotel, and insurance .

To complement his bid, Smith teamed up with Los Angeles general manager Emil Joseph “Buzzie” Bavasi. Bavasi’s career with the Dodgers organization dated to 1940, first as a business and general manager for several minor-league affiliates before becoming general manager of the Dodgers in Brooklyn in November 1950. As GM, Bavasi assembled the talent that would win four World Series and eight NL pennants between 1952 and 1966. With Walter O’Malley ensconced as Dodgers owner, Bavasi was effectively blocked from moving any higher within the organization. Seeking to join the ownership ranks and with O’Malley’s promise of support,3 Bavasi focused on expansion teams. With Smith promising about one-third of the team, the match was made.

Together, the Smith-Bavasi team provided a formidable combination of financial strength and baseball experience. Noting the area population of one million (and growing), Bavasi detected the potential for success: “If everybody in the city of San Diego attends one game, we’ll do all right.”4 In addition, community support for major-league sports was evidenced in November 1965, when 72 percent of those voting approved city bonds that would finance construction of the 50,000-seat San Diego Stadium. While the ballpark would initially house the American Football League’s Chargers, baseball officialdom took notice that the multipurpose facility could also accommodate a baseball team.

Together, the Smith-Bavasi team provided a formidable combination of financial strength and baseball experience. Noting the area population of one million (and growing), Bavasi detected the potential for success: “If everybody in the city of San Diego attends one game, we’ll do all right.”4 In addition, community support for major-league sports was evidenced in November 1965, when 72 percent of those voting approved city bonds that would finance construction of the 50,000-seat San Diego Stadium. While the ballpark would initially house the American Football League’s Chargers, baseball officialdom took notice that the multipurpose facility could also accommodate a baseball team.

The National League was seeking to expand in the late 1960s, but its hand was forced by the American League. Attempting to assuage Missouri Sen. Stuart Symington over Kansas City’s loss of the Athletics to Oakland, the AL agreed in October 1967 to expand by admitting Kansas City and Seattle for the 1969 season. Although the move caught the NL by surprise, it agreed to expand as well during the 1967 Winter Meetings in Mexico City. In voting to expand, the NL did not commit to expanding in concert with the AL. That uncertainty did not dissuade cities from preparing their pitches as San Diego, Dallas-Fort Worth, Buffalo, Milwaukee, and Montreal emerged as the serious contenders.

To evaluate the applicants, the NL appointed an expansion committee of O’Malley, John Galbreath of Pittsburgh, and Houston’s Roy Hofheinz. The composition of the committee was important in two respects. Not only did Bavasi have a close ally on the committee in O’Malley, but it was assumed that Hofheinz would block Dallas-Fort Worth in order to keep the Texas market to the Astros.

The NL convened in Chicago on May 27, 1968, with increasing expectations that the two expansion cities would be chosen for the 1969 season. After 10 hours of deliberations, a likely consequence of the unanimity requirement, NL President Warren Giles announced that San Diego and Montreal were accepted into the league.

Although it was assumed that Bavasi’s status as a baseball insider would assist the city’s bid, it was revealed later how close the Padres came to missing out. To some surprise, the NL accepted Montreal unanimously early in the voting. Buffalo clinched nine votes, but San Francisco’s Horace Stoneham held out for San Diego.5 At one point, San Diego had the support of only four owners as some Eastern owners lobbied colleagues for two Eastern cities.

After 18 ballots, momentum shifted away from Buffalo with San Diego’s bid the beneficiary. When the contenders were called into the meeting room, O’Malley tipped off Bavasi to the result with a smile followed by the question, “You got your ulcer yet?”6 had not accompanied Bavasi to Chicago but sent his attorney, Douglas Giddings.

After speaking with Smith, Giddings reported, “He was happy but he wondered why the meeting lasted so long.”7 Smith expressed his appreciation later: “I am gratified that years of planning and dreaming have come to reality today. … The action in Chicago by the NL owners is another expression of confidence in the great future that lies ahead for San Diego.”8

The Smith Years: Building a major league team

In the aftermath of the NL meeting and with mere months before spring training, attention shifted quickly to assembling San Diego’s major-league organization. At the executive level, Smith was named chairman of the board, Bavasi would serve as president, and Eddie Leishman was elevated from the general-manager position of the PCL Padres to the same spot with San Diego’s new NL club. The NL set the expansion fee at $10 million, the first $1 million of which was due on August 15. Of the $10 million aggregate, $6 million would be allocated to compensate the other NL clubs for each of the 30 players to be taken during the expansion draft. The Padres officially joined the NL with a $6 million payment on January 28, 1969, with the remaining $3 million to be paid in installments.

With the franchise in hand, the Padres turned to negotiating contracts for local radio and television rights and a lease for San Diego Stadium. The Padres hoped to maximize local radio and television given that the expansion clubs would not receive a share of national television revenue until the 1972 season. However, San Diego was hemmed in by the two-club Los Angeles market to the north and the Mexican border to the south. This caused some concern that the Padres would be hampered in their local negotiations. The team and local station KOGO announced an agreement at the end of July 1968 for both radio and television rights.

Although the Pacific Coast League iteration of the Padres was already playing at San Diego Stadium, a new lease was required for the major league team. After several rounds of negotiations that became stuck on the issue of a city subsidy to defray some of the costs to obtain the franchise, the club and the city delivered two tentative agreements to the City Council on August 1.

The parties to the first agreement were the city and the Padres, under which the club would pay a rental fee of 8 percent of ticket revenue over the 20-year lease term. The second agreement was between the city and San Diego Stadium Management Co., formed by the Padres to manage, operate, and promote the 50,000-seat ballpark for nonbaseball uses. The city would pay the management company the actual costs to maintain and operate the stadium on an agreed annual budget plus a 10 percent management fee. In addition, the city agreed to a subsidy of approximately $2.1 million in annual installments over the first seven years of the agreement, amounts intended to be reimbursed over the final 13 years of the agreement.

Early speculation on the managerial appointment focused on Dodgers third-base coach Preston Gomez and then-PCL Padres’ manager Bob Skinner. The PCL Padres were the Triple-A affiliate of the Phillies, and they tapped Skinner in mid-June 1968 to replace Gene Mauch in the Philadelphia dugout. While Mauch was believed to have interest in managing the NL Padres, Bavasi hired Gomez on August 29 on a one-year contract. The Cuban-born Gomez would be the first Latino hired to manage in the major leagues. At the introductory press conference, Leishman commented, “There were other people we considered, but Preston is the man we wanted most.”9 Leishman also viewed Gomez’s reputation as a teacher to be an important asset in assembling a new, young team to compete in the NL.10

The expansion draft provided the main opportunity to harvest a roster capable of competing at the major-league level. Bavasi lured 20-year scouting veteran Bob Fontaine away from Pittsburgh to run San Diego’s scouting operation. Bavasi nonetheless had his own idea of the team he hoped to assemble: “The thing we have in mind is to concentrate on good fielders, ballplayers who can run and control a bat. Naturally, we’ll be after strength down the middle. … The ground is hard at [San Diego Stadium] and we must have a good center fielder.”11

Under the expansion-draft rules, San Diego and Montreal would each select 30 players from the 10 established NL clubs. The draft occurred on October 14, 1968, in the Versailles Room of Montreal’s Windsor Hotel, the same location as the National Hockey League’s “Second Six” expansion draft ahead of the 1967-68 season. San Diego won a coin flip with Montreal for the right to pick first, and the Padres used that choice to select Downtown Ollie Brown from the Giants. Brown, a 24-year-old outfielder with a strong throwing arm, had slumped in 1968 after hitting .267 with 13 home runs in 1967.

With its second pick, San Diego chose pitcher Dave Giusti from St. Louis. Giusti had been traded from Houston to the NL champions the week before the draft and made no attempt to hide his feelings. “Nobody in St. Louis told me this was going to happen. I wanted to work for a championship club.”12 The Padres rounded out their first batch of selections with Dick Selma, 9-10, 2.75 ERA with the Mets; Al Santorini, a 20-year-old right-hander from the Braves organization; and Jose Arcia, a “good glove, weak bat” second baseman from the Cubs.

The Padres brass targeted youth throughout the draft, selecting players like Clay Kirby, a 20-year-old right-hander from the Cardinals organization; Fred Kendall, 19-year-old catcher from the Reds system; Julio Morales, an outfielder and another 19-year-old; Nate Colbert, a 22-year-old first baseman-outfielder who hit .264 in 1968 for the Astros’ Triple-A club in Oklahoma City; and Jerry DaVanon, a 23-year-old shortstop from the Cardinals organization and a native San Diegan. Unlike Giusti, he was excited to join the Padres. “Being picked by San Diego was the nicest surprise I’ve ever had,” DaVanon said.13

After the draft, the differing strategies between the Padres and Expos became readily apparent. The Expos certainly had more familiar names in veterans Maury Wills, Donn Clendenon, Manny Mota, and Jesus Alou. Bavasi mused, “We drafted players who are on the verge of becoming real big leaguers and Montreal drafted a bunch of players who are trying to stay in the majors.”14 Bavasi explained the club’s expansion draft strategy to San Diego Union columnist Jack Murphy: “Our job is to give fans a good show, and I don’t think you can do it with veterans.”15 Leishman added, “The club is tailored to fit a big park such as San Diego Stadium. We wanted speed, pitching, and defense.”16

The Padres waited for the Chargers to conclude their 1968 AFL season before making a concerted push for season-ticket sales. In that department, the Padres were lagging behind their Montreal expansion brethren. The Dodgers’ Don Drysdale and the Giants’ Willie Mays assisted the Padres’ efforts by recording radio spots to let San Diegans know they would be visiting during the coming season.17

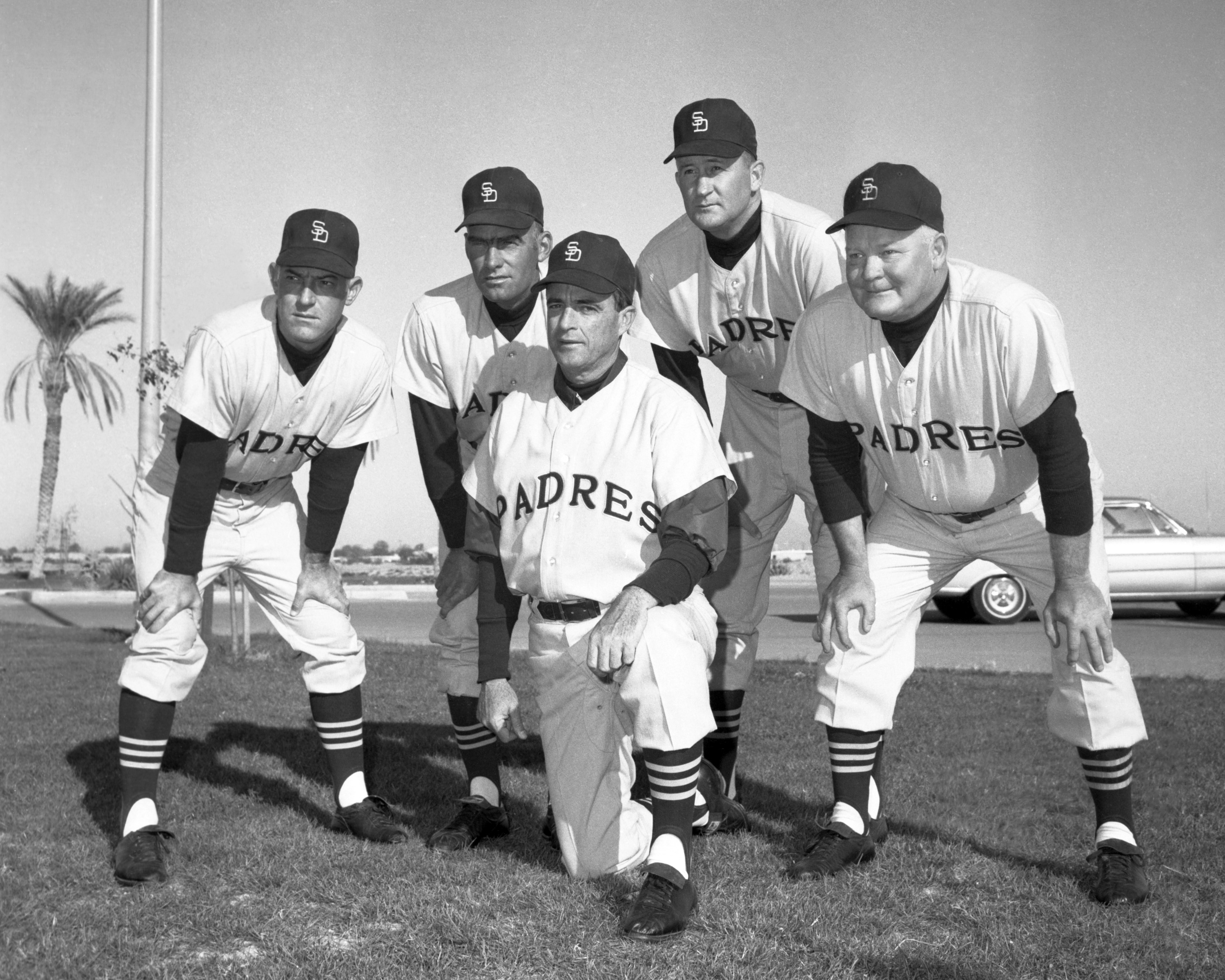

The 1969 Padres coaches gather around manager Preston Gomez during spring training in Yuma, Arizona. Left to right are coaches Sparky Anderson, Wally Moon, Roger Craig, and Whitey Wietelmann. (COURTESY OF TOM LARWIN)

There was some concern that the decision to keep the Padres moniker contributed to tepid ticket sales. Bavasi favored dropping the name, but was overridden by both Smith and apparent fan sentiment. Smith’s influence brought around Bavasi as the latter declared, “It’s a beautiful name, very apt and descriptive.”18 The swinging friar logo as well as the brown and gold color scheme debuted in November, and the club unveiled its uniforms in December. As the 1969 season approached, Bavasi’s initial concerns appeared to be manifested in still-disappointing ticket sales. Bavasi explained, “When people see or hear the name Padres they still think of minor-league baseball.”19

For their first spring training, the Padres selected Yuma, Arizona, over Mesa-Tempe, Arizona, and Imperial Valley, California. The Cactus League was a natural fit for the Padres, and the circuit would include seven teams for 1969: San Diego, San Francisco, Oakland, Seattle, California, Cleveland, and the Chicago Cubs. The Padres used temporary facilities and a remodeled Keegan Field while the City of Yuma built a permanent complex with four fields in time for 1970.

The new San Diego Padres made their NL debut on April 8 at San Diego Stadium against the Houston Astros. Bavasi maintained his optimism about the new venture despite having to revise downward his hopes for a bumper crowd on Opening Day. He commented, “San Diego is either a major-league city or it isn’t. I think it is and I believe I made the right decision.”20 Although the attendance of 23,370 fell short of expectations, the on-field result did not disappoint. Scattering five hits and backed by Ed Spiezio’s line-drive home run in the fifth and an RBI double by Brown, Selma secured the first win in Padres history, 2-1.

The Smith Years Continued: The constant specter of relocation

Despite the Opening Day success, the 1969 Padres struggled on and off the field. On the field, the Padres completed the opening series sweep of the Astros, but finished April at 9-14. The Padres were 24-30 on June 4, but proceeded to drop 31 of their next 36 games to establish a firm hold on the NL West Division cellar. Chris Cannizzaro became the first Padre selected for the All-Star Game, although he did not play. With the team collapsing on the field, attendance followed suit. The attendance barely topped a half-million; at 512,970, the Padres drew about 160,000 fewer fans than the Seattle Pilots, their American League West Coast expansion counterpart, who moved to Milwaukee in April 1970 after the team’s bankruptcy. Attendance was such an issue for the Padres that Buffalo and New Orleans inquired about relocation in July.21 The Padres finished 52-110, the same record as the Expos. In a debut season filled with ups and (a lot of) downs, San Diego was now a major-league city.

Throughout the Smith years, the club was dogged by poor performances on and off the field.

Expansion draftees Colbert and Kirby become the early stars of the club, and the Padres continued the strategy of building with youth. The results lagged, however, and the team could not escape the NL West basement. Relocation rumors also persisted as disappointing attendance figures suggested San Diego was unable (or maybe unwilling) to support major-league baseball.

With relocation such a persistent concern, the Padres Action Team and Chamber of Commerce organized to sell partial season tickets for the 1972 season. With a young team and improved offense, there were signs of preseason optimism. Leishman said, “If we get off well and stay around .500, I’m sure the attendance will pick up.”22 A slow start doomed the Padres once again. Bavasi fired Gomez after 11 games and replaced him with third-base coach Don Zimmer. The move provided a temporary respite for the Padres’ ails, and large crowds were attracted to the San Diego Stadium for series in May against the Dodgers and Reds. By the end of June, however, the team was in last place once again. Colbert had a great year (38 HRs, 111 RBIs), but he was the only one. A weak lineup and poor pitching ensured a last-place finish in the NL West.

Bavasi tried to quash rumors of a move to Washington, D.C., or Toronto, and he could point to improved attendance by about 85,000 over 1971. Washington-area lawyer Edward Bennett Williams and businessman Joseph Danzansky were known to have been sniffing around the Padres as a replacement for the Senators, who had decamped to Arlington, Texas, for the 1972 season. Before the San Diego Sportscasters-Sports Writers Association meeting in September 1972, Bavasi proclaimed, “I’ve come here to put an end to all of the scare stories — the Padres definitely are staying in San Diego.”23 Danzansky’s interest had a figure attached to it as he tabled an $11.75 million bid for the Padres in November 1972 with the clear intent of moving the team to Washington.

Bavasi continued to champion San Diego, and argued that the critics should not judge the city until the team became competitive.24 There were practical financial issues that needed to be resolved for the team to be successful. The Padres were estimated to have lost $2 million in their first four seasons. As would become evident, Smith did not have much liquidity to absorb these losses.

In addition to the attendance issues, the Padres and the city were in a conflict over stadium advertising, which the city had retained the right to sell. Bavasi observed, however, that the scoreboard advertising panels sold by the city featured competitors of the team, including Smith’s U.S. National Bank, leading some radio sponsors not to renew for the 1973 season. Bavasi believed the problem would only increase over time and enlarge the differences in broadcast revenues between the Padres and other teams.25 Though the ads provided approximately $40,000 to the city, Mayor Pete Wilson agreed to help the club work through lease and advertising issues and also committed to help with season-ticket sales.

On December 22, 1972, the club provided San Diego baseball fans with an early Christmas gift (depending on one’s view of those early Padres teams) by announcing their intent to stay in San Diego for the 1973 season. Bavasi referred to Smith as “the only Santa Claus in the baseball business.”26 The city stayed with its carrot and stick approach: offering help with the lease while reminding the team that the lease had a 20-year term. Making good on his promise, Wilson teamed up with 75 local businessmen in January to launch a drive to sell 10,000 “mini” season tickets, or the equivalent of 3,000 full-season packages.27 Wilson said, “This is a good young club — better than people realize –and it deserves public support. Up to now, the support hasn’t been good enough.”28

Lurking in the background, Smith’s financial empire was beginning to crumble. The Internal Revenue Service and the Securities and Exchange Commission were taking interest in his business affairs. He would have to sell, and soon. With respect to the Padres, Smith had borrowed most of the money required to pay the NL expansion fee, requiring annual interest payments of $700,000. San Diego Union sportswriter Jack Murphy wrote that Smith would be unable to make the interest payment due in May 1973, illustrating the depth of Smith’s situation. Meanwhile, the Padres were not exactly luring the populace to the ballpark as another poor start ruined the season before it really started. The Padres had the good fortune to draft Dave Winfield from the University of Minnesota, but future prospects would have to provide any good news for Padres fans.

On May 27, 1973, Smith announced that he had signed a letter of intent to sell to Danzansky for $12 million. Smith claimed that he wished the team would stay but he did not see how the situation would work out. Bavasi stated that any move was “not an indictment of San Diego. I can’t blame the town or the people.”29 Nonetheless, Bavasi opened talks with potential Japanese investors. He asserted, “I intend to exhaust every effort I can to keep the Padres in San Diego.”30

On August 1 Bavasi revealed that those talks had come to naught. Ultimately, Bavasi was limited in his ability to prevent Smith from acting unilaterally. Although it was thought that Bavasi had actual equity in the Padres, his supposed 32 percent ownership was illusory. That is, it had been intended for Bavasi to acquire his stake over time through profits generated by the team; none, however, had been earned since the team’s formation.31 Possibly seeking to placate the club’s nerve center, Danzansky offered jobs to Bavasi and his son, Peter, with the relocated club for 1974.

If Danzansky intended to follow through on relocating the Padres to Washington, he would have to overcome opposition from the City of San Diego and skepticism from the NL owners who would have to approve the sale and relocation. The city made clear its intent to fight back, and went to court to block any move. There remained more than a decade on the club’s lease of San Diego Stadium, and the city stood to lose millions without its primary tenant.

Within the NL, there appeared to be little enthusiasm to plant the league flag in a twice-failed AL city. Before flying to Washington to meet Danzansky on September 5, Bavasi offered, “I’m going to be very honest with Joe and tell him that several owners are violently opposed to the move.”32 Two weeks later, the NL held a daylong meeting in Chicago that provided no resolution other than a 30-day delay on taking a vote. It appeared that five or six clubs opposed the deal, and nine votes from 12 would be needed to approve the sale.33

Meanwhile, Smith’s legal and financial woes with federal agencies continued to pile up. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency declared U.S. National Bank to be insolvent in October, the nation’s largest-ever bank failure at that time. The IRS and SEC continued to investigate Smith’s affairs. The IRS claimed that Smith owed $22.8 million in back taxes and interest, and the SEC sued Smith and other executives for fraud against shareholders of Westgate and U.S. National Bank.

Against the backdrop of multiple federal inquiries and Danzansky’s bid looking like a nonstarter, Smith announced on October 5 that he had found another buyer willing to keep the team in San Diego. Marjorie L. Everett, CEO of the Hollywood Park Race Track and other tracks around the country, assembled a group that agreed to buy the club for around $10 million. Everett’s group included music composer Burt Bacharach, orthopedic surgeon Robert Kerlan, and Vernon Underwood (chair of Hollywood Park Race Track board), but some regarded Everett as “only slightly less controversial than gas rationing.”34

Opposition to Everett among NL owners related to testimony she provided in the bribery and conspiracy trial of Judge (and former Governor) Otto Kerner in Illinois. Everett sold stock in Chicago-area race tracks to Kerner for which he made a profit, a transaction apparently related to securing favorable racing dates. Everett claimed she was a victim of extortion over lost racing dates and was never charged with bribery or any other wrongdoing. Her lawyer, Neil Papiano, said, “Marge was investigated by every law enforcement agency you can think of and everyone gave her a clean bill of health.”35 Wilson also argued that she should be approved as Padres owner, noting that the city also had made inquiries of law enforcement.36

NL owners appeared unpersuaded. Heading into the Winter Meetings in Houston, four owners were said to oppose the sale to the Everett group.37 There were also rumors of finding someone to operate the team in San Diego in 1974 and then moving the Padres to Seattle, New Orleans, or Toronto for the 1975 season; it had not escaped baseball’s attention that Seattle and New Orleans were building domed stadiums scheduled to open in 1975.38

On December 6, 1973, the NL formally rejected Everett’s bid but provided conditional approval to Danzansky’s. The condition included a 15-day window to resolve San Diego’s $12 million lawsuit over the remaining years on the lease and provide an indemnification to the NL against $5 million in possible damages. During that window, the city also filed a federal antitrust suit seeking $24 million in damages, which if successful would treble to $72 million under the antitrust laws. The suit named a host of baseball and public officials, alleging a conspiracy to prevent San Diego from lawfully operating its stadium in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. Damages included lost revenues, destruction of the city’s business relationships, loss of and inability to get another baseball team, and loss of associated revenues from tourism.39

With obstacles emerging, Danzansky remained excited but restrained. He was working to secure the indemnity requested by the NL, but it was clear that there were limits to the financial risk he would assume to acquire the Padres. Danzansky asserted, “We just want a club that is free and unencumbered. We are not prepared to take an inordinate risk more than our $12 million that we are paying for the club.”40 To provide the indemnity, he approached Smith about changing the terms of the payouts. Originally, Danzansky and Smith agreed to a payment of $9 million in immediate cash with the remaining $3 million to be paid out over a longer term; Danzansky now sought to provide $7 million in cash upon sale with $5 million held in reserve for the requested indemnification.41

Danzansky could not arrange a satisfactory indemnification and the league rescinded its conditional approval on December 21. One week later, Everett appeared back in the picture with Smith accepting a renewed offer of around $9 million for the team. Part of the bid’s attraction was that Smith had a final $750,000 installment on his expansion fee coming due, and the Everett group sweetened the deal by agreeing to make payment on January 5.42

The NL still was not having Everett and again rejected her bid for the club on January 9. The vote was 9 to 3 against Everett, with only San Francisco and Cincinnati joining San Diego in favoring the sale. NL President Chub Feeney refused to provide an explanation, but Papiano and Wilson each suspected that the Kerner issue was just an excuse and that the NL really wanted to choose its own group that would move the team.43 In rejecting the bid, the league would have to return the installment payment to Everett.

The ownership saga left the Padres entering 1974 with uncertainty about their owner and their home. Bavasi’s efforts to manage baseball operations were hindered by a dwindling supply of working capital. On January 11 Wilson claimed he had spoken with three groups interested in buying the team, but Bavasi quickly disputed the claim: “There is no line forming to buy the team, at least not to my knowledge.”44

Spring training was about six weeks away, and the team had no idea if it was staying or going. There were no contracts for radio or television in place for the coming season,45 and the club was forced to ask the city for $71,000 in order to prevent 10 players from becoming free agents. Wilson assisted with obtaining the funds, calling the payment an advance on money owed by the city to the Padres’ stadium management company.

The Ray Kroc Years: Stability, splurging, and building a pennant winner

Just when it seemed the situation was at its bleakest, San Diego finally had the owner and stability it needed. On January 23, 1974, McDonald’s founder and chairman Ray Kroc reached an agreement with Smith to purchase the team for $12 million in cash while also committing to keeping the Padres in San Diego. Kroc announced his confidence in San Diego: “I am totally inclined to keep the team in San Diego. … I think San Diego can be a great sports town.”46

With a personal fortune of around $500 million, Kroc clearly possessed the financial wherewithal to turn the Padres into a contender. His wife, Joan, told him he would be “nuts” to buy the team,47 but Kroc bought the team with a sportsman’s enthusiasm: “Baseball is my sport. I want to have fun with an expensive hobby.”48 Kroc believed he could turn around the club and, drawing upon his background, bring fans into the ballpark. Kroc said, “A winning team, a fighting team, a personality team will draw, just like a great show will be a success.”49 He planned for amenities such as a stadium club and package deals with hotels and restaurants as well as 4:00 P.M. or 5:00 P.M. start times for weekday games.50

The NL unanimously approved the sale on January 31. There was some last-minute drama as Smith threatened to cancel the sale if the IRS attached Kroc’s check, a situation that Kroc made clear was Smith’s problem. Smith’s legal woes followed him for years; he was ultimately convicted of income-tax evasion and embezzlement but would serve only seven months tending to roses at an honor camp.51

Kroc quickly negotiated a new lease with the city that would keep the Padres at San Diego Stadium for the foreseeable future. The city agreed to take over day-to-day stadium operations, and Kroc extended a personal guarantee in relation to the lease.52 Under the terms, the Padres would get one-third of parking revenue and all concession revenue, and the club received veto power over ballpark advertisers but none of the income. The city would continue to receive 8 percent of gross receipts, but also get 50 cents per person for attendance over 800,000 after 1978.53

Kroc announced that he would retain Buzzie and Peter Bavasi, but it became apparent that Kroc would be a more hands-on owner than Smith was. Kroc said, “I’ll be a very active owner, but I’ll try to stay out of Buzzie’s hair.”54 The tradeoff for having an active owner was that Kroc’s money would give Bavasi greater flexibility to build a contender. Bavasi observed, “We will be in a position, financially, to compete with the other clubs.”55 Kroc expanded on his view about club responsibilities under his ownership. He stated, “I won’t interfere in the management of the club. Buzzie will have the manager of his choice. My line is marketing and merchandising: I’ve been in the food and beverage business all my life. I’ll concentrate on the quality and cleanliness at the ballpark. It will be a place where people can come to have fun.”56

However things turned out, Murphy wrote about the fundamental difference between Smith and Kroc as owners: “For the first time since the birth of the San Diego ball club in 1969, there is no speculation the franchise will fail and be moved elsewhere.”57 Murphy added, “The team’s new owner already is uniquely popular in this town. People have decided he is a man who can be trusted.”58

With the ownership situation resolved, there remained the not insignificant matter of preparing for the 1974 baseball season. The front office had adopted a dual track approach to the 1973-74 offseason: trying to create the economic conditions that would permit the team to stay in San Diego and shaking up a roster with little idea about where the team would play. In such a climate where ownership and location seemed likely to change by the week, the Padres engineered trades for established stars Willie McCovey, Matty Alou, and Bobby Tolan.

The anticipation manifested itself with a crowd exceeding 39,000 for the home opener against the Astros. Fans showed their appreciation to Kroc through a pregame standing ovation. The on-field results did not go as hoped, and the Padres trailed badly late in the game. Kroc used the public address microphone to let the fans know, “Ladies and gentlemen, I suffer with you.”59 Shortly afterward, he opined to the crowd “that this is the most stupid baseball playing I’ve ever seen.”60 Kroc later apologized for the comment.

Stable ownership and additional promotions helped drive attendance over one million, far exceeding any previous season’s attendance. Injuries cursed the roster, including Tolan missing two months after getting hurt in midseason, and the Padres finished last in the NL West once again, with a record of 60-102. In a sign of future aggressiveness in the free-agent market, though, Kroc flashed the cash in a bid for new free agent Catfish Hunter but lost out to the Yankees; he also pursued Andy Messersmith the following offseason with similar lack of success.

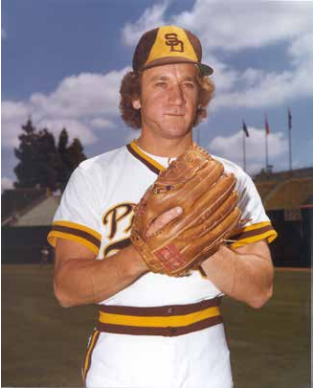

In 1975 Randy Jones emerged as a star talent and the Padres finally get out of the NL West cellar with a fourth-place finish at 71-91. Important for the business side, attendance continued to climb, reaching 1.28 million. Jones continued his ascent into baseball’s elite by earning the All-Star Game start and the Cy Young Award for the 1976 season. The Padres did not see a noticeable improvement in results, with a 73-89 record, but attendance almost hit 1.5 million.

In 1975 Randy Jones emerged as a star talent and the Padres finally get out of the NL West cellar with a fourth-place finish at 71-91. Important for the business side, attendance continued to climb, reaching 1.28 million. Jones continued his ascent into baseball’s elite by earning the All-Star Game start and the Cy Young Award for the 1976 season. The Padres did not see a noticeable improvement in results, with a 73-89 record, but attendance almost hit 1.5 million.

With free agency implemented throughout baseball before the 1977 season, Kroc followed through on earlier forays into the market. This time the Padres landed Rollie Fingers (six years, $1.6 million) and Gene Tenace (five years, $1.8 million) while also acquiring George Hendrick through a trade with Cleveland. The Padres appeared poised for a leap, but the team struggled. Manager John McNamara paid for the failures with his job on May 29, replaced by the unpopular Alvin Dark. Kroc thought well of McNamara personally, but argued, “Mac is a very wholesome guy but we’re in the baseball business, not the fellowship business. The players by their performances have shown us we aren’t getting the leadership we need.”61 Despite adding Dave Kingman on June 15, the team finished fifth and suffered its first attendance decline of the Kroc era.

Tensions from the managerial change created a simmering situation that culminated in Bavasi’s departure shortly before the conclusion of the 1977 season. The decision to fire McNamara had been Kroc’s, not Bavasi’s. Bavasi declared, “I’m still a John McNamara man” when he resigned.62 Bavasi was further irritated that Dark opened a direct channel of communication with Kroc. When Bavasi also somehow found himself embroiled in apparent disagreements with Joan Kroc, he bolted. While he may not have had the freedom of action under Kroc that he had with Smith, Bavasi acknowledged the resources that Kroc brought to the team. Bavasi said, “It’s a shame Ray Kroc couldn’t have been our original owner.”63 Kroc reached a financial settlement with Bavasi, leading the latter to quip, “If I had known Ray was going to be this generous, I would have resigned two years ago.”64

Within weeks, Gene Autry hired Bavasi to lead the front office of the California Angels. Kroc promoted Bob Fontaine to GM with a directive to make trades and acquire young players. In the shake-up, Kroc took Bavasi’s title as president and named son-in-law Ballard Smith as executive vice president. Fontaine would have the final say on trades, and Smith would look after the balance sheet. Smith explained, “People have the impression Ray is making a lot of money off the Padres, but that is hardly the case. My ambition right now is to see that we break even this year.”65

The Padres, however, appeared not to be taking concrete steps to rein in spending ahead of the 1978 season. Kroc authorized the signing of Oscar Gamble on a six-year deal worth $2 million. The club also signed Gaylord Perry as a free agent from Texas and coaxed Mickey Lolich from retirement. For good measure, Kroc bought an airplane for club travel. The despised Dark was replaced by Roger Craig in the dugout. The first half of the campaign was plagued with the now-characteristic inconsistency, but rookie Ozzie Smith made his big-league debut and ensconced himself at shortstop with a Rookie of the Year runner-up campaign.

San Diego hosted its first All-Star Game on July 11, with Winfield and Fingers representing the host team. After the break, a 10-game winning streak starting in late July carried the team over .500. While never really threatening to become a player in the divisional race, the Padres remained on the happy side of the ledger and completed their first-ever winning season at 84-78. Attendance surged to 1.67 million, another club attendance record under the Kroc regime.

Kroc continued to show aggressiveness in recruiting players to San Diego. He lost out to the Phillies in trying to sign Pete Rose, but another slow start to the 1979 season caused Kroc to get ahead of himself in the coming free-agent market. Kroc vowed to spend $5 million to $10 million for talent; he did not stop at an amount, however. Rather, he specifically named Graig Nettles and Joe Morgan as his targets “if they become free agents.”66 Their current employers were not pleased, and Yankees owner George Steinbrenner and Reds President Dick Wagner complained to Commissioner Bowie Kuhn about tampering. Kroc apologized, saying, “I made a slip of the tongue.” He also took himself out of the contention to bid for Nettles or Morgan, but made clear, “I’ll do what it takes to improve the team.”67

Despite the apology, Kuhn fined Kroc $100,000, the largest in baseball history at the time. Kroc chose not to appeal and also stepped down as Padres president, handing the title to Smith. He sounded defeated and irritated in saying, “Baseball has brought me nothing but aggravation, it can go to hell.”68 It appeared he might give up more than his title in suggesting, “There’s a lot more future in hamburgers than in baseball.”69

Although upset in the aftermath of the fine, Kroc remained the pivotal person among the Padres leadership. The promotions continued, culminating in the hiring of Ted Giannoulas, better known as the San Diego Chicken, to fire up the fans. Kroc explained, “When you own something, you never give up control. I own the Padres. I don’t work on the day-to-day stuff, but I own the club.”70 The negative results on the field — a fifth-place finish in 1979 despite Winfield’s best season yet — caused attendance to slump. Craig paid for the failures with his job, to be replaced by Padres broadcaster Jerry Coleman.

Indeed, neither Nettles nor Morgan joined the Padres in the 1979-80 offseason, and Fontaine’s overtures to pitchers Nolan Ryan and Dave Goltz also came up short. Fontaine managed to part with some of Kroc’s millions in signing Rick Wise and John Curtis. Those contracts paled in comparison to the riches that appeared to await Winfield. Going into the 1980 campaign, the club and the player were millions apart. Another disappointing start to a season did not help matters. Fontaine was fired in midseason and Smith hired Jack McKeon as his replacement, a move that would pay dividends in crafting an eventual pennant winner. The team, however, finished in the cellar and attendance dropped to 1.14 million, a loss of more than a half-million ticket buyers since the high of 1978.

As expected, Winfield played his last season in San Diego, trading Padres brown for Yankee pinstripes (and plenty of Yankees green). With the passing of longtime sportswriter Jack Murphy in September, the ballpark would be renamed for the San Diego Union columnist.

Padres owner Ray Kroc greets the San Diego Chicken before a game in the late 1970s. (SAN DIEGO PADRES)

McKeon moved Coleman back to the broadcast booth for the 1981 season, hiring the former Dodger and Senator Frank Howard to man the dugout. The rookie manager presided over a season that had not one, but two, last-place finishes. As McKeon began remaking the roster, the team had a youthful look with most regulars in their mid-20s. The inexperienced team brought up the rear of both halves of the strike-shortened 1981 season, notable perhaps only for the crowd of 52,608 that took up Kroc’s offer of free admission to the first home game after the end of the two-month midseason work stoppage. McKeon fired Howard after the season, but the hire of Dick Williams would bring championship managerial experience to the club.

McKeon faced the prospect of another star player bolting in free agency, as shortstop Ozzie Smith and his agent agitated for a long-term deal beyond the Padres’ means (even Kroc’s). McKeon found a trading partner in Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog, and the teams agreed to an even exchange of shortstops, Smith for Garry Templeton. Under Williams’s tutelage, the Padres had baseball’s second-best record during the first half of the 1982 season, and only the division rival Atlanta Braves were better. The Braves ended up winning the NL West, while the Padres slumped to 81-81 by season’s end. The second half witnessed the big-league debut of Tony Gwynn, but also the arrest and suspension of Alan Wiggins for cocaine possession.

Attendance rebounded near the high of 1978, and appeared likely to be eclipsed in 1983 after the free-agent signing of longtime Dodgers iron man Steve Garvey on a five-year, $6.5 million contract. Kroc told Garvey, “Steve, I think you can make a difference here,” and Garvey told Ray and Joan, “We’re going to have some fun. We’re going to have a winner.”71 It was not to be … at least not right away. Garvey missed the final 62 games of the season with the first significant injury of his career, and the club hovered below .500 for most of the season.

The year 1984 started inauspiciously for the Padres with Kroc’s death on January 14, only eight days after he made Goose Gossage the highest-paid pitcher in baseball with a five-year, $6.25 million deal. Gossage had visited the ailing Kroc in the hospital, and told him, “I hope I can help your ballclub, Mr. Kroc.”72 Kroc replied, “I hope you can, too, with what we’re paying you.”73 His memory would be honored with “RAK” to be worn on the jersey sleeves throughout the 1984 season.

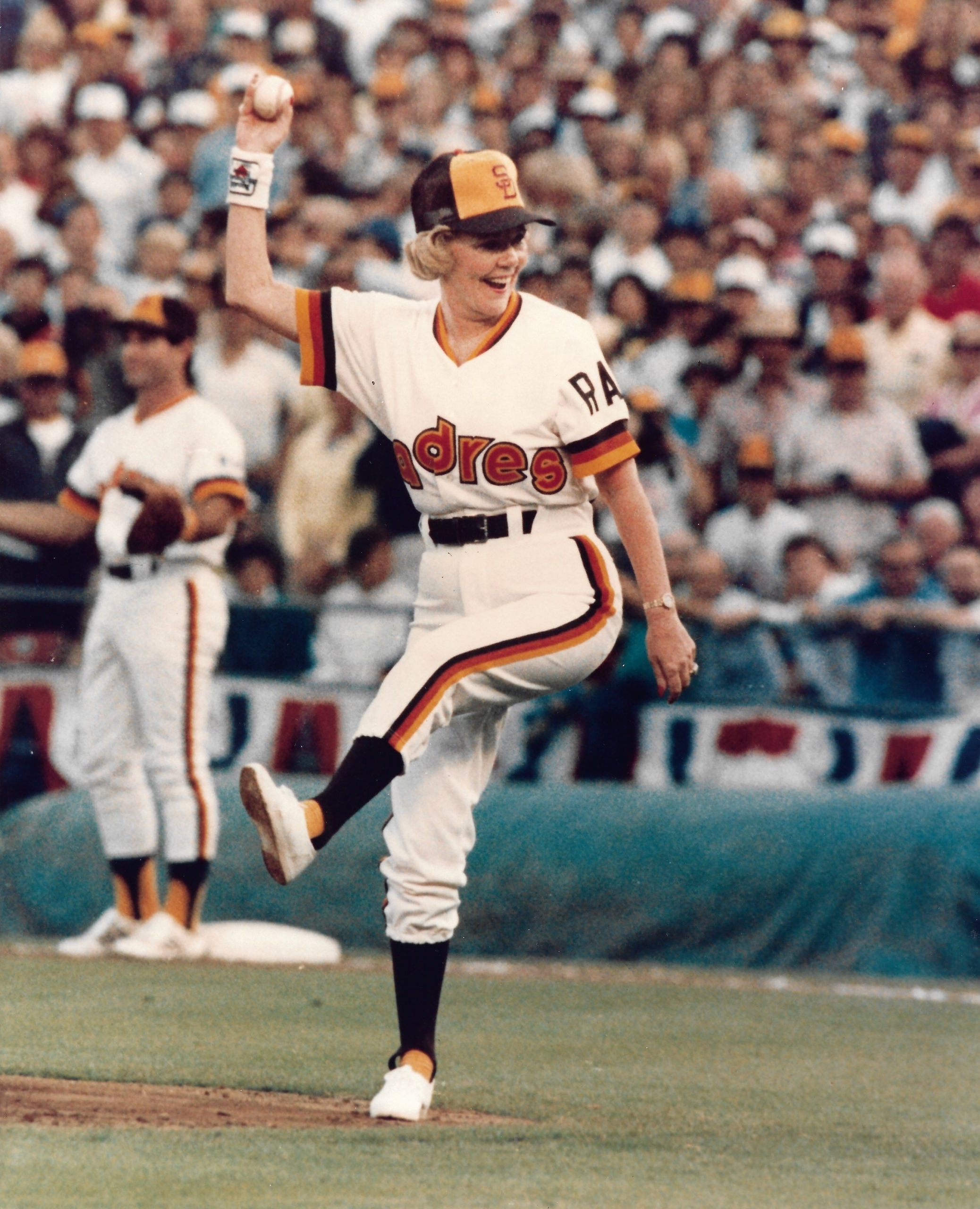

With Kroc’s passing, Joan became team president and chairwoman of the board. Smith remained in charge of day-to-day operations, and said on Kroc’s death, “This doesn’t affect the future of the club at all. Ray made provision for operations to continue here. … Joan is as committed to fielding a winner here as Ray was.”74

Five years after his tampering charge, Kroc posthumously got his man when McKeon traded for Nettles, a San Diego native, in a trade involving pitcher Eric Rasmussen. The Padres started the 1984 season quickly with a 15-8 April record. After a minor slump in May, the Padres reclaimed first place on June 9 and never surrendered the division lead. Not even a minor media circus surrounding revelations that pitchers Eric Show, Dave Dravecky, and Mark Thurmond (who combined for 75 starts) were members of the right-wing John Birch Society could derail the Padres season. The West Division title was clinched on September 20 with a 5-4 win over the last-place Giants. Utilityman Kurt Bevacqua said, “I wish Ray was here to enjoy this, because people don’t understand what a fan he really was. I think all of us who knew him have dedicated this season to his memory.”75

At 92-70, the Padres won the division with 12 games to spare. Almost 2 million visited Jack Murphy Stadium as the Padres broke their single-season attendance record for the fifth time since 1974. Capacity crowds also filled the ballpark, and team’s coffers, to witness the team’s first postseason. After the Padres reversed a two-games-to-none deficit to defeat the Chicago Cubs in the NL Championship Series, the 104-win Detroit Tigers proved too great an obstacle in the World Series.

Joan Kroc Years: Tumult in the clubhouse, and the sale that wasn’t before the sale that was

Although the Padres generally contended for the remainder of the decade, the club could not repeat the success of 1984. It was not for lack of trying. San Diego traded for 1983 AL Cy Young Award winner LaMarr Hoyt in December 1984 and signed free agents Jerry Royster and Tim Stoddard in January 1985. The club sported new uniforms as well as a new logo, with a more traditional pinstripe uniform replacing brown pullovers. Despite the new faces and the new look, the club could not overcome injuries and could do no better than 83-79 in 1985. The fans, however, bettered their previous mark, as attendance surpassed 2.2 million for another club record.

Although the Padres generally contended for the remainder of the decade, the club could not repeat the success of 1984. It was not for lack of trying. San Diego traded for 1983 AL Cy Young Award winner LaMarr Hoyt in December 1984 and signed free agents Jerry Royster and Tim Stoddard in January 1985. The club sported new uniforms as well as a new logo, with a more traditional pinstripe uniform replacing brown pullovers. Despite the new faces and the new look, the club could not overcome injuries and could do no better than 83-79 in 1985. The fans, however, bettered their previous mark, as attendance surpassed 2.2 million for another club record.

The following year was one of discontent, throwing off a season that seemed to promise so much. Prior to the season, Williams resigned after losing an apparent power struggle with McKeon and Smith. Joan Kroc commented at one point that if the executives sought to get rid of the manager, “They’ll have to use their own money because they’re not using mine.”76 Steve Boros became the first new manager since 1981. Hoyt was detained by US customs officials in one incident, was arrested in another, and began the 1986 season in alcohol rehabilitation.

In May, Joan Kroc revealed her plan to sell the ballclub. Although Kroc preferred to sell to her son-in-law, Smith was not interested. Smith provoked the ire of the clubhouse by banning beer from all employee areas at the ballpark, citing increased liability insurance premiums as the justification. Gossage slammed Smith and Kroc, saying, “I guess Ballard and Joan don’t have anything better to do. Their lives are so boring.”77

Gossage continued his feud with management later in the season. Smith had told players that the team would not offer multiyear contracts unless drug testing was implemented. In an interview, Gossage complained that Smith “wants choir boys and not winning players” and doesn’t know anything and doesn’t care.”78 Kroc and Smith handed Gossage a 30-day suspension without pay on August 29. Gossage later apologized. The season ended 74-88, and Boros was out after a single season. Larry Bowa would helm the Padres ship in 1987, and it would be lighter ship with the Padres trimming payroll by releasing or trading Hoyt, Nettles, Royster, Terry Kennedy, Kevin McReynolds, and Dave LaPoint.

Meanwhile, the club remained on the market with Kroc rumored to be seeking $50 million.79 Garvey, still a member of the playing staff, claimed two groups approached him about teaming up on a bid. The first baseman said, “We’re just in elementary stages. There’s nothing concrete, but there is an interest — based around the idea that the club stays in San Diego — and the potential for the franchise, really, is unlimited.”80

Ultimately, Garvey was unsuccessful in putting together a group. Kroc, however, appeared to have found a buyer from the ranks of her fellow owners. On March 26, 1987, Kroc announced that she had accepted an from Seattle Mariners owner George Argyros, a deal conditioned on his unloading his current club. Terms were not disclosed, but the deal was estimated within the $50 million-$65 million range. Argyros lived up in the coast in Newport Beach, and explained, “My decision is related to where I spend my time and where it makes sense to have my interests.”81

At the time, Kroc spoke optimistically about Argyros. She said, “I think he is going to be good for baseball and San Diego.”82 Argyros rejected one offer to buy the Mariners and proved unable to secure the funds need to purchase the Padres, so Kroc pulled the plug on Argyros and put the team back on the market on May 29. Kroc explained, “Both Mr. Argyros and I entered negotiations thinking this would be a simple, uncomplicated deal. … [I]t had become quite clear that it could not be completed on time. I didn’t feel it was fair to the community to keep things in limbo.”83

Kroc quickly took the club off the market, however. The Padres had opened the 1987 season with a staggering 12-42 record, and it was clear that care was needed to improve the team. Kroc stated, “Another buyer is the last thing in the world I’m looking for now. We’re going to turn everything around. There will be no sale or discussion of sale this year, period.”84 She also wanted to negotiate a new lease with the city of San Diego to ensure that the Padres would not move.85

Kroc hired former NL President Chub Feeney to the club presidency in June. Perhaps the only surprise is that club avoided losing 100 games in a miserable season. Kroc seemed content to holding onto the Padres, saying, “God willing, I expect to own the Padres for a long time.”86 Kroc also signed a 13-year lease with the city, a move that appeared to secure the team’s immediate future.

The 1988 season seemed destined for another bumpy ride after a 16-30 start that cost Bowa his job. The Padres had tried to land Kirk Gibson when the Tigers slugger hit the market after the collusion cases. The Padres and Dodgers both offered three-year deals, but the Dodgers’ offer came in higher by $300,000. McKeon replaced Bowa in the dugout, and the team turned around the season to finish in third place at 83-78.

During a Saturday night game against the Astros on September 24, unhappy fans made known their displeasure about the Padres executive management by unfurling a “Scrub Chub” banner at Jack Murphy Stadium. Feeney responded by flipping the bird. His attempts to deny having done so were disproven with pictures of the incident, leading the longtime baseball executive to resign at the end of the season. Kroc made clear, however, that he was pushed and did not jump. She said, “Only one person handled Chub — me.”87

Reflecting on her deceased husband, Kroc added, “I asked myself what Ray would do. Quite simply, Ray loved his customers, and the fans are our customers. We never would allow them to be insulted.”88 The Padres presidency was Feeney’s last job in baseball.

With new leadership needed, Kroc named Dick Freeman as club president and hired Tal Smith to look after day-to-day operations. Off the late-season surge, the Padres sought to strengthen for the 1989 season. The loss of pitcher Andy Hawkins to the Yankees was offset by the free-agent signing of Bruce Hurst from the Red Sox. Trades for first baseman Jack Clark and pitcher Walt Terrell, along with an improved contract for Tony Gwynn, seemed to signal the Padres’ intent to challenge the World Series champion Dodgers in the NL West. The Padres spent most of the season near the .500 mark, however, and another September surge got them no closer than three games behind the division-winning Giants in the end.

The club on the upswing, Kroc placed the Padres on the market in October. Ownership responsibilities appeared to have sapped the philanthropist of her enthusiasm for the ballclub. Kroc explained, “It’s time for someone with renewed energy to take over, to get involved day to day.”89 It was also apparent that the experience from two years before of dealing with Argyros left a sour taste. “I’m never going through the agony of the George Argyros sale again. … Only quality people of integrity need apply.”90

She turned to her son-in-law, player agent Jerry Kapstein, to help with the sale. Kapstein opined that the team was worth $100 million, a price tag that did not appear to dampen interest. Among those linked to the Padres were Los Angeles Lakers owner Jerry Buss, Los Angeles Kings owner Bruce McNall, San Diego businessman Larry Lawrence, diet moguls Sid and Jenny Craig, and even Garvey. A paternity suit squashed Garvey’s potential candidacy before it gained much traction. At one point, it appeared the Craigs would be the buyers. They irritated Kroc, however, by breaking the news of their intended purchase at a local luncheon in defiance of Kroc’s wishes for a news blackout.91 Ultimately, the Craigs could not meet Kroc’s financing requirements and their bid was scuttled.

With the 1990 season approaching and the club still on the market, Kroc added oversight of club operations to Kapstein’s responsibilities. Kroc explained the move: “[T]o be free to carry out my travel plans this summer, I have asked Jerry to step in as my personal representative. As long as it takes, we’re going to ride out the waves and give this city a darn good team.”92 Freeman and McKeon would report to Kapstein, a situation of which McKeon approved. McKeon said, “I think it’s a good move. … [H]is placement in this particular role blends right in with his other job as the representative of selling the club.”93 Trader Jack focused on preparing for the 1990 season in which the Padres were favored to take the NL West. Although closer Mark Davis signed with the Royals, McKeon signed Craig Lefferts from division rival San Francisco as his replacement. He also traded for Joe Carter to boost the offense and also signed him to an extension.

Jack Murphy Stadium, in San Diego’s Mission Valley neighborhood, was home to the Padres from 1969 to 2003. (SAN DIEGO PADRES)

The Werner Years: From tire fire to fire sale

One week before the 1990 season opened, Kroc found her buyer. On April 2 she agreed to sell to an ownership group headed by television producer Tom Werner for $90 million. The investor group eventually swelled to 15 members, leading Werner to joke, “We’ve got enough people now for a partners-players baseball game.”94 The NL provided its unanimous approval on June 13 in Cleveland, and, for the first time since 1974, the team’s owner was not named Kroc.

Werner was not expected to make major changes as Freeman and McKeon remained in place.

The Werner group had an unpropitious start when a promotion on July 25 to celebrate “Working Women’s Night” backfired. Werner, who produced Roseanne among other TV shows, invited comedian Roseanne Barr to sing the national anthem prior to the start of a game against the Reds on July 25. It did not go well. Barr’s off-key performance closed with spitting and crotch-grabbing. The team issued a statement suggesting that the audio feed was to blame. Gwynn remarked, “It was a disgrace,” and Show called it “[a] total embarrassment to the club.”95 The incident sparked national condemnation, including from the White House. Lost in the fallout was that the Padres swept that day’s doubleheader. The following month, a chastened Werner said, “What I hope is that the fans will come to realize our heart is in the right place.”96

The on-field product failed to meet the preseason expectations. The Padres foundered in the first half, and McKeon resigned as manager during the All-Star break with the Padres at 37-43, 13½ games behind the Reds. McKeon had told Werner he would like to leave the manager’s chair in order to focus on baseball operations. Greg Riddoch assumed managerial responsibilities from McKeon, but a 75-87 season cost McKeon the job he had wanted to keep. Werner fired McKeon on September 21 and tapped Mets assistant GM Joe McIlvaine to orient the team toward greater scouting and development. McIlvaine said, “We are here to develop the best player development system in baseball.”97 In announcing the move, Werner said, “We all respect Jack. He’s done some wonderful things, but it’s important for us to get to the next level.”98 Despite the sack, McKeon said he was “not bitter” and added, “I think I am leaving them a good club.”99 McKeon was the first move in the housecleaning that included 25 front-office dismissals in the first weeks of the offseason.

The Werner group made over more than just the front office. Since their inception and despite several uniform changes, the Padres’ colors had remained brown and gold. Harkening to the PCL Padres days, the team adopted navy blue and orange for the 1991 season. One of Werner’s partners, Art Rivkin, said, “All I’ve heard about the old uniforms is complaints.”100 Bob Payne, another partner, added, “We didn’t really care for brown.”101 Despite various fan campaigns over the years, brown would be exiled from the Padres’ color palate for three decades.

Likely unrelated to the new look, the Padres finished just about .500 in each of the next two seasons. McIlvaine had traded Joe Carter and Roberto Alomar to Toronto for Fred McGriff and Tony Fernandez before the 1991 season, and then acquired Gary Sheffield during spring training 1992, but the club could not break through. In a sign of a coming cash crunch, Werner vetoed McIlvaine’s offer to Danny Tartabull after the 1991 season. Werner revealed that some partners wanted out, as the cost of owning a piece of a major-league club was becoming too much to bear. Though expressing unhappiness about baseball’s financial direction, Werner denied that the Padres were on the market. It became clear what the Padres’ financial direction would be. Werner said after the 1992 season, “Spending more money doesn’t mean you win. We spent last year, and it didn’t work.”102

After losses of $8 million and amid persistent rumors of cash-flow problems, Werner ordered McIlvaine to trade Fernandez before he could exercise his contract option and also slash payroll by $7 million.103 McIlvaine would resign in June 1993, replaced by Randy Smith, who became baseball’s youngest GM at 29. Werner opined, “You’d have to have your head examined to invest in a baseball team.”104

The 1993 season appeared to be a disaster waiting to happen. Hurst made clear he wanted out, in stating, “[T]he way things are going around here, I sure don’t want to be back.”105 Werner hoped that increased revenue-sharing among major-league teams would help even out the economic imbalance. He argued, “I’m fighting for the Padres’ economic survival.”106 Werner continued to deny any plans to sell the team. Washington-area attorney Bart Fisher claimed that his group offered $150 million to buy the Padres and move them to the District of Columbia or Northern Virginia. Werner repeated his mantra: “As I’ve said before, the team’s not for sale.”107

By the 1993 trade deadline, Hurst got his wish and was moved, along with Darrin Jackson, Sheffield, McGriff, and Greg Harris. The Padres finished 61-101, in seventh place for the first time now that the expansion Colorado Rockies joined the NL West. Several players acquired in return would prove to be productive major leaguers but, as the losing continued, the Werner regime became increasingly unpopular.

Werner and his group began coming to the realization that greater financial wherewithal would be required. Payne, antagonist of the old color scheme, admitted, “We need a larger capital base. … We have some owners who are unwilling or unable to keep contributing to make up the shortfall.”108 The owners also recognized that a new ballpark would be required to generate additional revenue and hired consultants to develop financing options.

As for the 1994 season, the Werner group projected a $4 million loss even after the prior season’s fire sale.109 Perhaps the lone bright spot of the season was Tony Gwynn’s charge to become baseball’s first .400 hitter since San Diego native Ted Williams in 1941. Meanwhile, attendance had cratered to the bottom of the major leagues. The situation became so embarrassing that the Padres had to ask the city to place tarps over the many empty seats in the upper deck. The season ended with a players strike that commenced August 12, removing any opportunity for Gwynn to improve his .394 batting average. The strike would claim the World Series among its casualties, but with a 47-70 mark, the Padres were never going to be a postseason factor. Manager Jim Riggleman left for the Cubs job in the offseason, and former catcher Bruce Bochy would commence a 25-year managerial career in the 1995 season.

As for the 1994 season, the Werner group projected a $4 million loss even after the prior season’s fire sale.109 Perhaps the lone bright spot of the season was Tony Gwynn’s charge to become baseball’s first .400 hitter since San Diego native Ted Williams in 1941. Meanwhile, attendance had cratered to the bottom of the major leagues. The situation became so embarrassing that the Padres had to ask the city to place tarps over the many empty seats in the upper deck. The season ended with a players strike that commenced August 12, removing any opportunity for Gwynn to improve his .394 batting average. The strike would claim the World Series among its casualties, but with a 47-70 mark, the Padres were never going to be a postseason factor. Manager Jim Riggleman left for the Cubs job in the offseason, and former catcher Bruce Bochy would commence a 25-year managerial career in the 1995 season.

The Moores Years: A pennant, Petco Park, and a prolonged exit

During baseball’s nuclear winter, the Werner group managed to find its exit strategy. After negotiations fizzled with a pair of Florida-based businessmen, Malcolm Glazer and Norton Herrick, Werner reached an agreement in principle with Texas-based software mogul John Moores in September. Moores owned a home in San Diego and pledged to attend every home game if successful in acquiring the Padres.110 The price was approximately $80 million, or less than what the Werner group paid to purchase the club from Joan Kroc.

Moores noted the timing of his purchase during baseball’s labor disruption. He said, “Everyone gets a historical footnote, and I suspect mine will be that I was the only person ever to buy a baseball team in the middle of a strike. I did it to have fun and don’t regret it for a second.”111 In making his play for the Padres, Moores teamed with former Orioles President and CEO Larry Lucchino. Moores lacked a background in baseball, and it was apparent. Lucchino would have a major hand in running the team.

Moores clearly brought deeper pockets to the club and said all the right things about being a different owner from Werner. He stated, “My goal is to stabilize the club financially so that it can be competitive on the field and accepted in the community. We’re here for the long haul, and it helps that we’re using my money and not someone else’s.”112

Werner’s unhappy tenure as Padres owner concluded on December 21, 1994, with baseball’s formal approval for the transfer. Lucchino assumed the club presidency from Freeman, and the Moores-Lucchino duo opted to retain Smith as the GM. One week later, the new ownership made an early mark as Smith engineered a 12-player trade with Houston with Ken Caminiti as the highlight acquisition. Moores commented, “We’re going to send the message forward that there’s a new direction — to field a solid, competitive, winning baseball team, and pay the money that’s required to do that.”113

In addition to ending the fire-sale era, Moores also wanted to solve the issue of San Diego’s supposedly constrained market and viewed Mexico as an opportunity to grow. Although the Padres had been on local Spanish-language radio since their inception, the team struggled to win the affection of potential Mexican fans on both sides of the border. The Dodgers had beaten the Padres to Southern California and also achieved goodwill among Mexican fans with the Fernandomania craze commencing in 1981.

When Moores and Lucchino took over, the latter was surprised to learn the team had no Spanish-speaking staff members.114 New ownership adopted the mantra, “We want to become Mexico’s team.”115 Hoping to create some of their own Fernandomania, the Padres signed the former Dodger Fernando Valenzuela for the 1995 season. In addition, Lucchino oversaw the opening of a merchandise store and ticket outlet in neighboring Tijuana, Mexico.116

The Padres also worked with the business community in San Diego and Tijuana and with the US Immigration and Naturalization Service in order to make border crossings easier for Sunday afternoon home games. Mexican fans could purchase discounted tickets and ride dedicated buses to and from Jack Murphy Stadium, and when they were at the ballpark, they were greeted with Spanish-speaking ushers and special concession areas.117

In August 1996 the Padres’ efforts to woo Mexican fans culminated in a three-game August series in Monterrey, Mexico, with Valenzuela starting and winning the opening game against the Mets. The Padres would receive a significant jump in attendance in 1996, and these efforts were seen as crucial to that result. In January 1997, the club expanded its connections across the Pacific Ocean through an agreement with Japan’s Chiba Lotte Marines intended to involve exchanges of prospects, coaches, and scouting information. In addition, Moores seemed to adopt a regular-guy persona through fan focus groups and scholarships to local schoolkids. Lucchino recognized the value of such direct engagement, noting that “[o]wnership is too often underappreciated as a marketing aspect. Fans do respond to stability, positive involvement by the owner.”118

Despite another losing record (70-74) for the 1995 season, the franchise seemed to have turned a proverbial corner. After Smith left for Detroit in the offseason, Kevin Towers took over as GM and began assembling the final pieces of an eventual division winner. Towers acquired Bob Tewksbury, Rickey Henderson, and Wally Joyner before the 1996 season and traded for Greg Vaughn at the deadline. The Padres battled to the wire against the Dodgers for the NL West crown. San Diego swept Los Angeles over the final weekend to win the NL West at 91-71 with attendance greater than 800,000 over the final full season of the Werner regime.

The division title earned the Padres their first postseason appearance since 1984, but St. Louis swept the Padres in the division series to ensure that there would be no repeat of 1984’s pennant. Individual honors went to Caminiti and Bochy in the form of the MVP and Manager of the Year, respectively.

First mooted seriously during the Werner administration, the issue of a new ballpark and its likely new revenue streams became a serious topic between the Padres and local officials during the 1996-1997 offseason. Jack Murphy Stadium had remained a shared facility with the Chargers, and the Chargers were in a much more favorable position economically than the Padres. Mayor Susan Golding and the Chargers agreed on renovations in 1995 that enclosed the stadium and increased capacity, partly for purposes of attracting a Super Bowl. There were additional suite and concessions revenue streams that favored the NFL team, to which the city also gave control of all advertising revenue at what would soon be renamed Qualcomm Stadium.

When the city and the telecommunications equipment services company agreed to a naming rights deal in 1997, the Padres did not receive any of the upfront $18 million fee received from Qualcomm. Lucchino had been attempting to make the best of the situation. He promoted the Padres aggressively and oversaw improvements such as the planting of palm trees outside the ballpark and the installation of a new JumboTron scoreboard.119

The situation was increasingly untenable for the Padres’ balance sheet. In December 1996 Golding appointed the Mayor’s Task Force on Padres Planning to explore questions related to the status of the Padres within the community, and whether a new ballpark was needed to ensure the financial viability of the club. By August 1997, Golding’s task force completed its work and concluded that the Padres needed a new ballpark, but where and how to finance it remained outstanding questions.

In response to the report, the City Council constituted the City of San Diego Task Force on Ballpark Planning with the charge of considering financing options and possible locations. After multiple public meetings and site visits, the task force delivered its report to the council in late January 1998 and the council accepted the recommendations several weeks later. The key components of the proposal were the development of a Ballpark District in the East Village neighborhood and estimated project costs of $452 million, about half of which would come from the city. The use of public money would require a public vote, and the City Council directed the city manager to work with the Padres to ensure that the issue appeared on the November 3, 1998, ballot.

Knowing a winning team might make for a happy voting public, the Padres moved to beef up the 1998 squad. The Padres had struggled to follow up their 1996 division-winning campaign, as a slow start for 1997 set the stage for a losing season. Management did not stand pat in the wake of the 76-86 season, however. To address a pitching staff that finished next to last in ERA, Towers acquired Kevin Brown from the fire-sale Florida Marlins and signed free agents Mark Langston and Greg Myers prior to the 1998 season. The new additions, along with holdovers including Caminiti, Steve Finley, and Joyner, took the payroll to $46 million, which led Moores to speculate about the team’s breakup if revenues did not keep up with expenses.120 The Padres were all-in on a successful 1998 season.

The Padres rode a fast start to a 19-7 record and five-game lead in the NL West entering May. After a blip caused the team to surrender the lead for a few days in early June, they hit another hot streak and took a 57-31 record into the All-Star break. Five Padres made the NL All-Star team. The Padres coasted to the division title, clinching on September 12 with an 8-7 win over Los Angeles in front of more than 60,000 fans.

The Padres rode a fast start to a 19-7 record and five-game lead in the NL West entering May. After a blip caused the team to surrender the lead for a few days in early June, they hit another hot streak and took a 57-31 record into the All-Star break. Five Padres made the NL All-Star team. The Padres coasted to the division title, clinching on September 12 with an 8-7 win over Los Angeles in front of more than 60,000 fans.

The Padres shattered their previous attendance record with more than 2.5 million spectators en route to a 98-win campaign, and massive crowds packed Qualcomm for the 1998 postseason. They took out the 102-win Astros and 106-win Braves in the NL playoffs, but the 114-win Yankees proved too much to overcome in a World Series that ended in a sweep. The good vibes of a pennant-winning campaign carried over to the November 3 election, in which 60 percent of voters approved Proposition C, authorizing the city to enter into negotiations with the Padres for a new ballpark.

Off the field, the Padres quickly were smacked by economic realities. There were only so many millions Moores could lose and the roster was picked apart. Moores had invested in a winning roster and claimed that he did not want to break up the team but argued that the club would need to focus on player development with a plan to increase payroll for the new ballpark’s expected opening in 2002. The Padres would defend their pennant without Caminiti, Finley, and Brown, all of whom left as free agents (with the latter signing a nine-figure deal with the Dodgers), as well as Vaughn and pitcher Joey Hamilton, traded to Cincinnati and Toronto, respectively. At $15.5 million over three years, the Padres signed Sterling Hitchcock to the somewhat ironic largest free agent deal in team history. Injuries further eroded the Padres’ ability to compete at the major-league level, and the team managed only 74 wins in a 1999 season notable for Gwynn topping 3,000 career hits. Lucchino enhanced the club’s scouting and player development programs and began focusing on acquiring young talent.

If 1999 was rough, 2000 was chaotic on and off the field. Injuries continued to decimate the team; the Padres would set NL records for the number of pitchers and players used during a season. Somehow, the team scratched out 76 wins. Attendance had remained relatively steady despite the lack of success but events would create questions about whether the ballpark would be completed.

In April, it was revealed that a city councilwoman had profited from the initial public offering of a company in which Moores had controlling interest. The councilwoman eventually resigned and pleaded guilty to two misdemeanors, and Moores was absolved of any wrongdoing, but this minor scandal delayed the sale of the municipal bonds to fund construction. Further, project opponents filed a series of lawsuits challenging various City Council actions and votes to advance the project. Construction on the new ballpark was halted for the year on September 29.

Moores issued a cash call to his partners for $20 million to fund expenses for the 2001 season as losses mounted. Gwynn filed for free agency after the season, but eventually re-signed with the Padres. On the bright side, Winfield was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame and later announced that he would be inducted as a Padre. In response, the club announced that his number would be retired. At midseason, Gwynn announced his retirement effective at the end of the season; in September, he learned he would become the next baseball coach at San Diego State University. Moores would pay for construction of what would become Tony Gwynn Stadium on the SDSU campus.

Gwynn played his final game on October 7 with more than 60,000 in attendance. Mr. Padre grounded out in a pinch-hit appearance in the ninth inning, but Rickey Henderson, who had signed prior to the 2001 season, doubled to lead off the first inning for his 3,000th hit. The day was about Gwynn, and Mayor Dick Murphy revealed that the address of the new ballpark would be 19 Tony Gwynn Drive.

Lucchino stepped down as president and CEO at the end of the season to join the new John Henry-Tom Werner ownership group in . Despite the changing of the guard with Bob Vizas assuming the club presidency, the stadium project got back on track. The city council signed off on a new bond issue in November by an 8-to-1 vote. The final lawsuit against the project was dismissed in January 2002, which cleared the way for the issuance of the bonds. Merrill Lynch purchased $169 million in municipal bonds on February 15, and construction restarted several days later.

The Padres moved into Petco Park for the 2004 season. (SAN DIEGO PADRES)

Originally slated to open in 2002, Petco Park was completed for the 2004 season. After five losing seasons following the 1998 World Series appearance, the Padres improved by 23 games (to 87-75 and third place) and drew over 3 million fans to their new home. The good times continued as the Padres won the NL West in 2005 and 2006, though they lost in the NL Division Series to the Cardinals each time. Bochy departed for San Francisco, and Bud Black began his own extended tenure as Padres manager in 2007. The Padres finished the season tied with the Rockies at 89-73 for the wild-card spot, but lost the tiebreaker to Colorado in an epic 13-inning clash at Coors Field. The Padres had been relevant for an extended run. Combined with the novelty of a new ballpark, attendance exceed the best mark at Qualcomm each of the first four years in the new park.

That novelty wore off quickly when the team cratered to a 63-99 record in 2008. Hemorrhaging season-ticket holders amid a rapid descent, the club saw its stability rattled further when Moores and his wife announced their plans to divorce. Under California’s community property laws, the split would be costly for Moores, and Moores placed the Padres on the market. In early 2009 former player agent and current Arizona Diamondbacks CEO Jeff Moorad assembled a group of 12 investors to buy the Padres from Moores. For purposes of the transaction, the Padres were valued at $500 million (which would involve some cash and debt assumption), and Moorad’s group intended to purchase the club over a five-year period on an installment plan through which 100percent of the club would be acquired gradually.

Moorad had been the Diamondbacks’ chief executive since 2004 and also owned 12 percent of the club, an issue that would need to be resolved. His sudden departure soured his relationship with Ken Kendrick, Arizona’s managing general partner. In fact, Kendrick initially refused to purchase Moorad’s shares.

Moorad was named vice chair and CEO, but Moores remained majority owner for the time being. The Padres appeared to have atrophied in recent seasons, and Moorad said many of the right things about regaining lost momentum. Moorad asserted, “I believe things can turn in a hurry and I’m optimistic that this club has a system in place that can certainly spark that turnaround.”121 He made season-ticket holders an early focus. The team had lost half of its season-ticket base between Petco’s opening in 2004 and 2009, and he intended to bring them back. To that end, he reduced ticket prices and increased game-day promotions. Moorad suggested that community support would be rewarded in stating that “to the extent that we feel the community is supporting the club, we’re going to invest every last dollar back into the product.”122

Moores had put $100 million into Padres operations during the delays to Petco Park’s construction, but the consequences of the losses meant cuts to the scouting and player-development budgets.123 Moorad reversed this trend. He fired Towers at the end of the 2009 season, replacing him with Red Sox assistant GM Jed Hoyer with the charge to develop players through improving the farm system; indeed, Hoyer did so before leaving for the Chicago Cubs after the 2011 season.